Are Value Managers Undervalued?

Growth Investing Has Outperformed Value for Quite Some Time Now, and the Market’s Taking Notice

Looking Back

If you’re an asset manager, then you’re probably aware of growth investors’ dominance over their value counterparts for the last ten or fifteen years. Since the Financial Crisis, it’s been all growth, which tends to outperform during sustained bull market runs and periods of monetary easing.

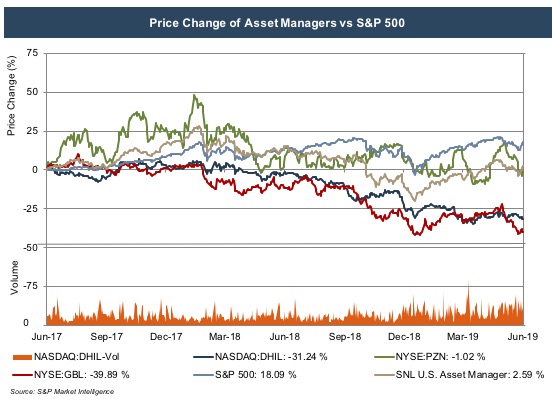

As most value and growth managers’ clients are primarily (performance chasing) institutional investors, this recent disparity has been particularly challenging for value investment firms looking to grow (or even maintain) their AUM balances. The market has clearly picked up on these issues, especially over the last couple of years – two out of the three public (and predominantly) value-oriented investment firms (Gabelli and Diamond Hill) are in bear market territory while the S&P is up nearly 20% since the Summer of 2017:

The economics behind the sector’s fall-out are relatively straightforward. Underperformance leads to outflows and contractions in AUM with corresponding declines in management fees and earnings. Even if the multiple doesn’t slip, the drop in profitability is enough to weigh on share prices. Unfortunately, the multiple did slip, and Gabelli and Diamond Hill have lost a third of their market cap during relatively favorable market conditions. As we’ve noted before, this multiple is a function of risk and growth, so the market either believes their growth prospects have diminished or their risk profile has elevated. In all likelihood, it’s a little bit of both, as growth will likely be adversely affected by lower demand for value products, while the risk of continued outflows remains high.

Looking at the Multiples

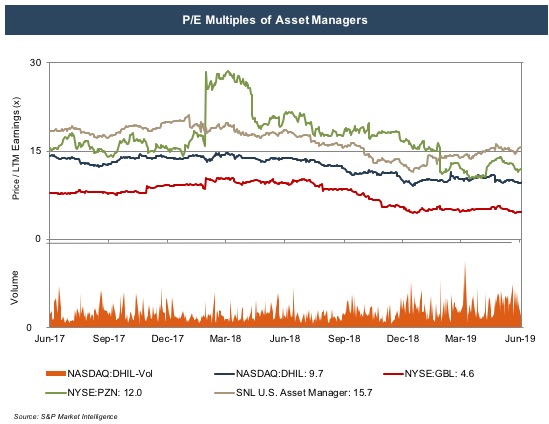

Against this backdrop, we address this post’s original question as to whether or not value managers are indeed undervalued at the moment. A quick glance at the P/E graph below reveals that two of these businesses are priced at less than 10x trailing twelve month (after-tax) earnings, while their RIA peers trade at 15.7x (on average) and the broader market is closer to 20x.

This is definitely at the lower end of a reasonable range, and is, once again, likely attributable to a particularly high-risk profile and lower growth prospects. The ten-plus year slough of relative underperformance versus growth investing and expectations for continued outflows are the likely culprits.

Still, some might contend that this is overblown, or at least short-sighted, if you believe in mean reversion or question the sustainability of the current trend. The last time growth dominated value by this margin was during the tech bubble when the Russell 2000 Growth Index outperformed its value counterpart by 68% (annualized) from October 1, 1998 to March 1, 2000 before giving it all back (and then some) over the next couple of years. The problem for value managers is most of their institutional clients emphasize relative performance over the prospect for mean reversion, so they’re going to have to improve their track records to recover lost AUM. That’s not always a given.

Even the world’s greatest value investor is struggling.

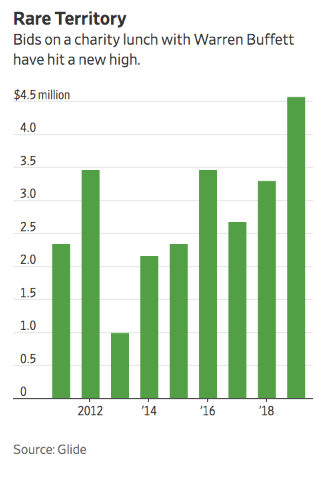

Even the world’s greatest value investor (and perhaps the greatest investor of all time) is struggling to keep pace with the market. Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway is up just 2% so far this year compared to just over 15% for the S&P 500 and 25% (on average) for the FANG stocks. Fortunately, this hasn’t curtailed Buffet’s ability to raise money for a good cause, as the current bid for his annual charity lunch currently resides at $4.6 million.

Buffet’s current predicament is not nearly as dire as 1999 during the Dot Com Crash when the S&P and NASDAQ appreciated 20% and 87%, respectively, while Berkshire lost 22%. Worth noting, however, is BRK-A gaining 32% the following year when the S&P and NASDAQ shed a respective 9% and 45%. We’re not forecasting that level of mean reversion but do want to emphasize how quickly relative outperformance can swing the other way.

Looking Forward

There are very good reasons why value managers’ stocks have performed so poorly over the last few years.

The bottom line is that there are very good reasons why value managers’ stocks have performed so poorly over the last few years. Significant underperformance relative to both the market and growth alternatives has led to continued outflows from institutional investors, which in turn has hampered AUM, revenue, and earnings growth despite relatively favorable market conditions. Since the multiple has also slid for these businesses, it appears that the market is anticipating more of the same. That’s probably true since their one, three, five, and ten year track records are lagging, which is what most institutional investors base their hiring and firing decisions on.

Regardless, we’re skeptical that this growth-over-value outperformance will persist much longer, given the cyclical nature of investment performance. It’s probably only a matter of time, and if it’s any time soon, that would make value managers (and Berkshire stock) very attractive investments. Otherwise, current valuation levels are justified, and it could be a very long time before the sector regains investor confidence.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights