Organic growth is a key metric for the RIA industry, but it’s also one that’s easy for many firms to ignore. Why is that? We think part of the answer lies in the prevailing revenue model of the industry, where fees are assessed against the market value of client assets. In any given year, market appreciation or depreciation is very likely to be the primary contributor to AUM and revenue growth (or decline). When markets can move AUM by 20% or more each year (as they have for the last two years), a few percentage points of organic growth seem meager by comparison.

Why then should firms focus on organic growth, when it’s often insignificant relative to market movements? The answer is that while markets may be the most important factor guiding changes in AUM from year-to-year, they’re not a factor that RIAs have any real influence over. Some firms may have clients with asset allocations that perform better or worse in a particular year, but, generally speaking, all firms are along for the ride. Unlike market growth, organic growth is not outside of the control of RIA owners, and thus it becomes a real differentiator between firms over time. If market growth is the tide that lifts (or lowers) all boats, organic growth is the engine on the boat.

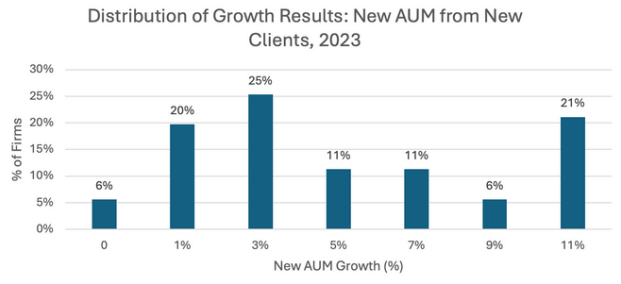

The Ensemble Practice and Blackrock have conducted a study on organic growth that looks at the distribution of organic growth across the industry, and the results are striking. For most of the industry, rates of organic growth follow a more-or-less normal looking distribution centered around 3%. There is however a separate group, about 20% of the industry, growing at double digit (11% or more) growth rates. This small group of firms seems to have cracked the code to unlocking meaningful organic growth, where it’s often an afterthought for the rest of the industry.

Source: True Ensemble Data Insights 2024 Growth Report - August 2024

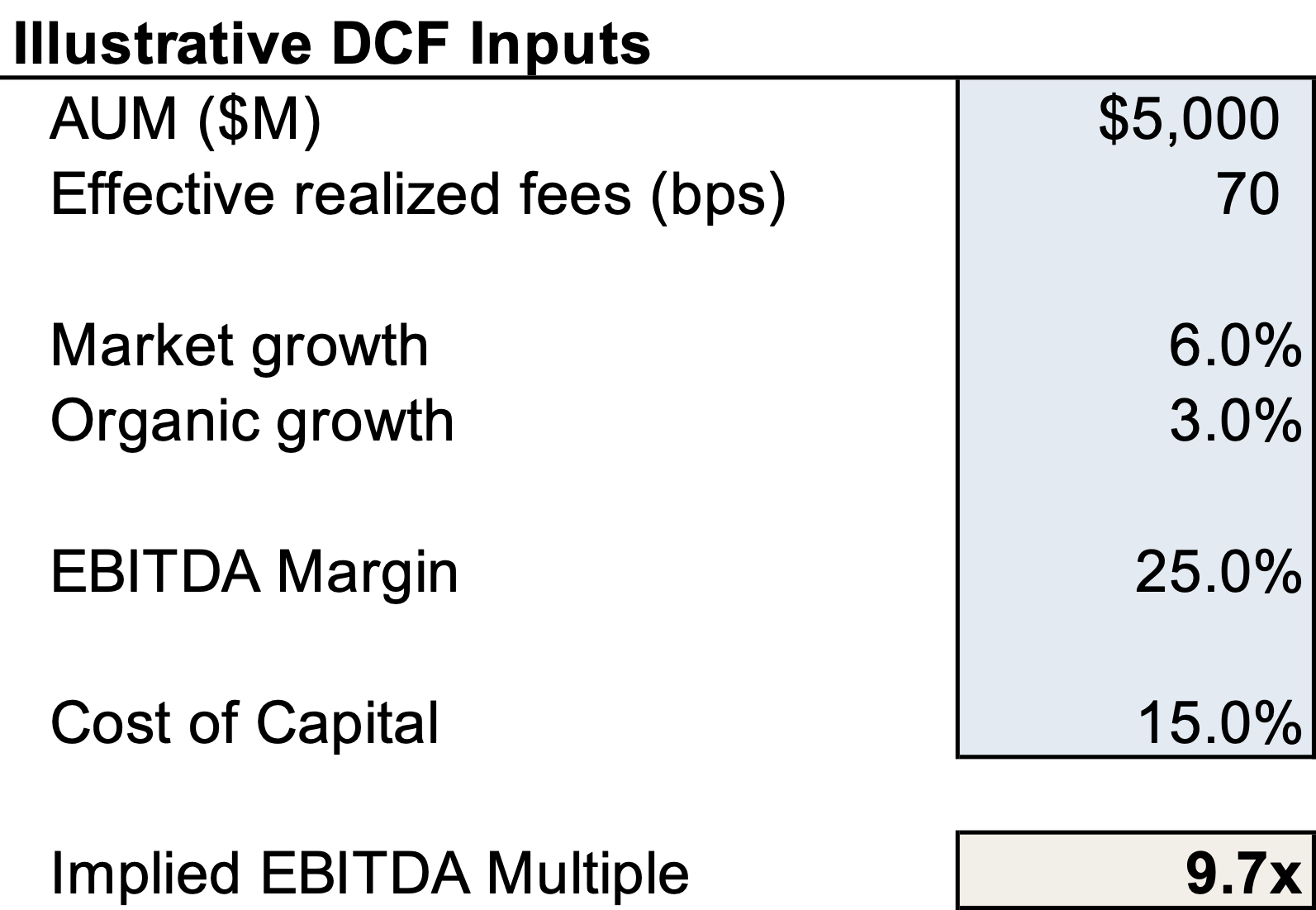

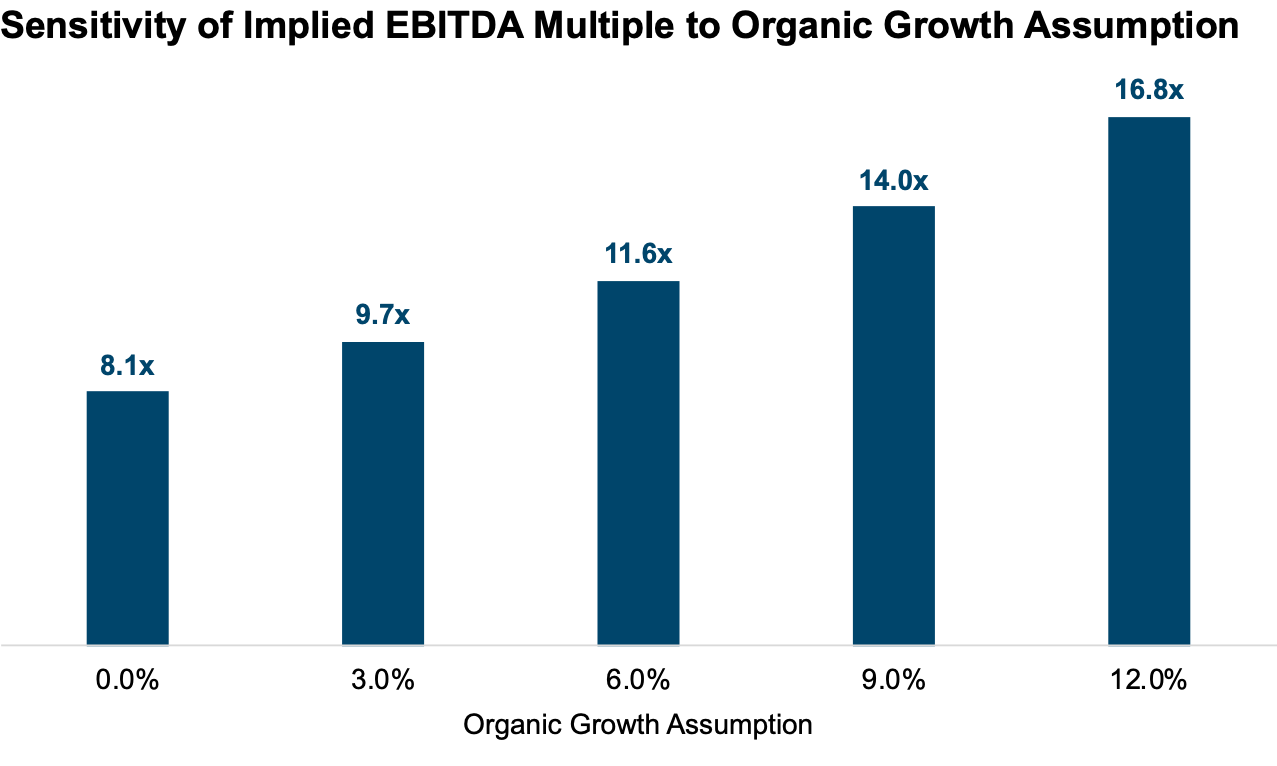

How do these disparities in organic growth impact firm valuations? To illustrate, consider the following simplified discounted cash flow model. A hypothetical firm managing $5 billion in assets earns realized fees of 70 basis points and generates a 25% EBITDA margin. Over a 10-year discrete forecast period, market growth is assumed to contribute 6% annually to AUM growth, and net organic growth is assumed to contribute 3% annually—or roughly the industry average excluding the high performers. At a 15% cost of capital, the implied EBITDA multiple is 9.7x.  What happens as we vary the net organic growth assumption? The chart below shows the sensitivity of the implied EBITDA multiple to different net organic growth assumptions. Holding the other assumptions constant, each percentage point of organic growth contributes to about a 0.5x to 1.0x increase in the EBITDA multiple. The result is that a firm growing at 12% organically would (in theory) command an EBITDA multiple of more than double that of a firm without any organic growth.

What happens as we vary the net organic growth assumption? The chart below shows the sensitivity of the implied EBITDA multiple to different net organic growth assumptions. Holding the other assumptions constant, each percentage point of organic growth contributes to about a 0.5x to 1.0x increase in the EBITDA multiple. The result is that a firm growing at 12% organically would (in theory) command an EBITDA multiple of more than double that of a firm without any organic growth.

Organic growth is far from the only assumption that impacts the EBITDA multiple a firm commands, but it is an impactful assumption in valuing the business and one that can vary widely from firm to firm. The range of observed transaction multiples for RIAs is also wide—there are data points ranging from mid-single digits to north of 20x. Various factors drive these differences, but efforts to rationalize those multiples often come back to discussions of organic growth. Of course, organic growth usually isn’t free.

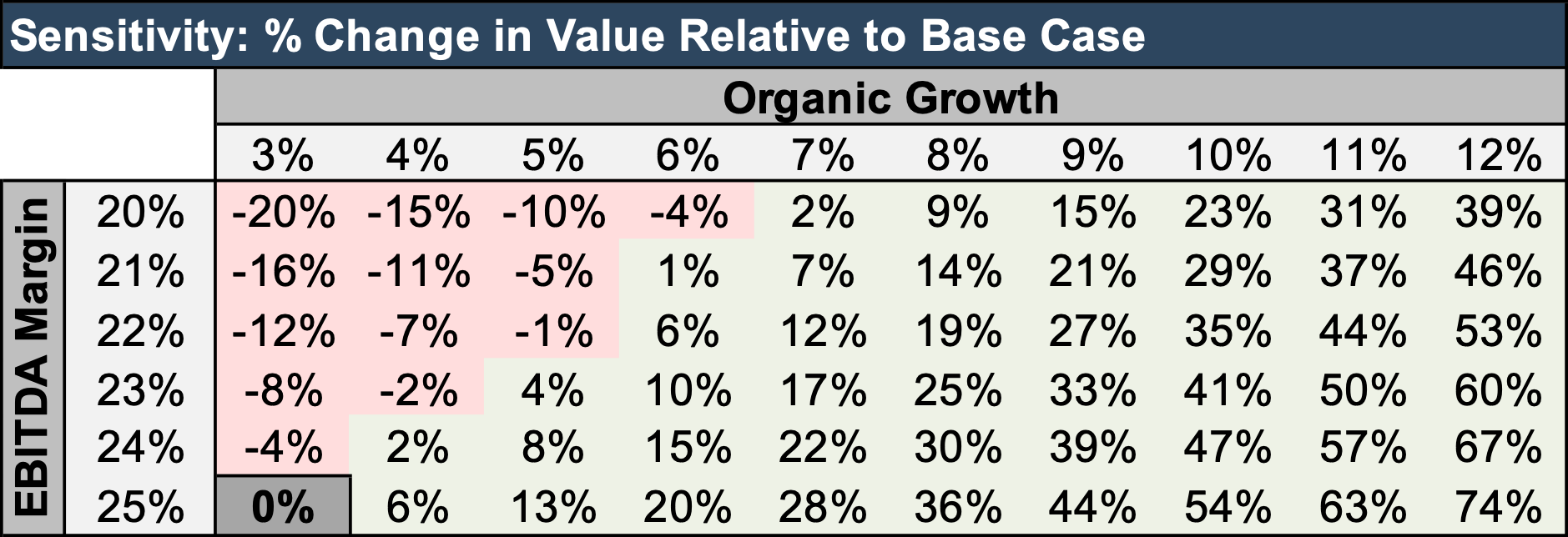

Firms that are growing rapidly through organic growth are often investing more significantly in marketing, spending more on business development incentives, recruiting new staff, etc. The tradeoff is that achieving higher organic growth often comes at the expense of a lower margin.

How should firms navigate this tradeoff? We’ve written before about how applying the lens of capital budgeting can be a useful perspective when thinking about investing in growth in a way that is accretive. Another way to analyze this tradeoff is to return to our illustrative DCF model and examine the interaction between margin and growth assumptions.

The sensitivity table below shows the change in value relative to a base case assuming a 25% EBITDA margin and 3% organic growth. What we see is that, generally speaking, a one percent decline in the EBITDA margin coupled with a one percent increase in organic growth is marginally accretive from a valuation perspective. If the ratio of organic growth gained to EBITDA margin sacrificed is greater than 1:1, the impact on valuation is even more accretive. The takeaway is that in the tradeoff between margin and growth, growth usually wins.

About Mercer Capital

We are a valuation firm that is organized according to industry specialization. Our Investment Management Team provides valuation, transaction, litigation, and consulting services to a client base consisting of asset managers, RIAs, trust companies, broker-dealers, PE firms, and alternative managers.