The value of asset and wealth management firms depends very much on context. In the valuation community, we refer to the context in which the firm is being valued as the “standard of value.” A standard of value imagines and abstracts the circumstances giving rise to a particular transaction. It is intended to control the identity of the buyer and the seller, the motivation and reasoning of the transaction, and the manner in which the transaction is executed.

In our world, the most common standard of value is fair market value, which applies to virtually all federal and estate tax valuation matters, including charitable gifts, estate tax issues, ad valorem taxes, and other tax-related issues. It is also commonly selected as the standard of value in buy-sell agreements for investment management firms. Fair market value has been defined in many court cases and in Internal Revenue Service Ruling 59-60. It is defined by the International Valuation Glossary as follows:

A Standard of Value considered to represent the price, expressed in terms of cash equivalents, at which property would change hands between a hypothetical willing and able buyer and a hypothetical willing and able seller, each acting at arms-length in an open and unrestricted market, when neither is under compulsion to buy or to sell and when both have reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.

Notably, the fair market value standard requires that the price be expressed in terms of cash equivalents. This is consistent with how many business owners think about the value of their business but is inconsistent with the reality of how many real-world transactions are structured.

It’s not unusual for investment management transactions to include earnout structures as a mechanism for bridging the gap between the price the acquirer wants to pay and the price the seller wants to receive. If buyer funding is an issue (as it often is in internal transactions), the deal may include deferred payments or seller financing.

It’s also commonplace for the seller to receive all or a portion of their consideration in buyer stock for which there is no active market (if the buyer is private) or which is subject to a lock-up period (if the buyer is public). Stock consideration is often denominated in dollars in purchase agreements, but (in the case of a private buyer) that raises the question: how is the value of the buyer stock determined? If the buyer stock is overvalued, the purchase price in a stock transaction may be similarly inflated. Sellers that take buyer stock in a transaction are effectively “buyers” of the acquirer, and it’s important to understand what you’re buying and how it’s valued.

A higher interest rate environment and market volatility over the last two years have contributed to transaction structures leaning more towards earnouts and equity consideration. According to Advisor Growth Strategies’ 2023 RIA Deal Room report, average cash consideration decreased from 77% of total consideration in 2021 to 67% of total consideration in 2022, while equity consideration increased from 21% to 25% and contingent increased from 2% to 8% of total consideration over the same time period. Anecdotally, we’ve seen that trend continue through 2023 and into 2024.

As deal structures have shifted from the certainty of cash in favor of earnouts and equity consideration, capturing the real economics of a transaction has become more complex. In order to reconcile real-world deal terms with fair market value, it is necessary to reduce the non-cash deal components into a cash equivalent value.

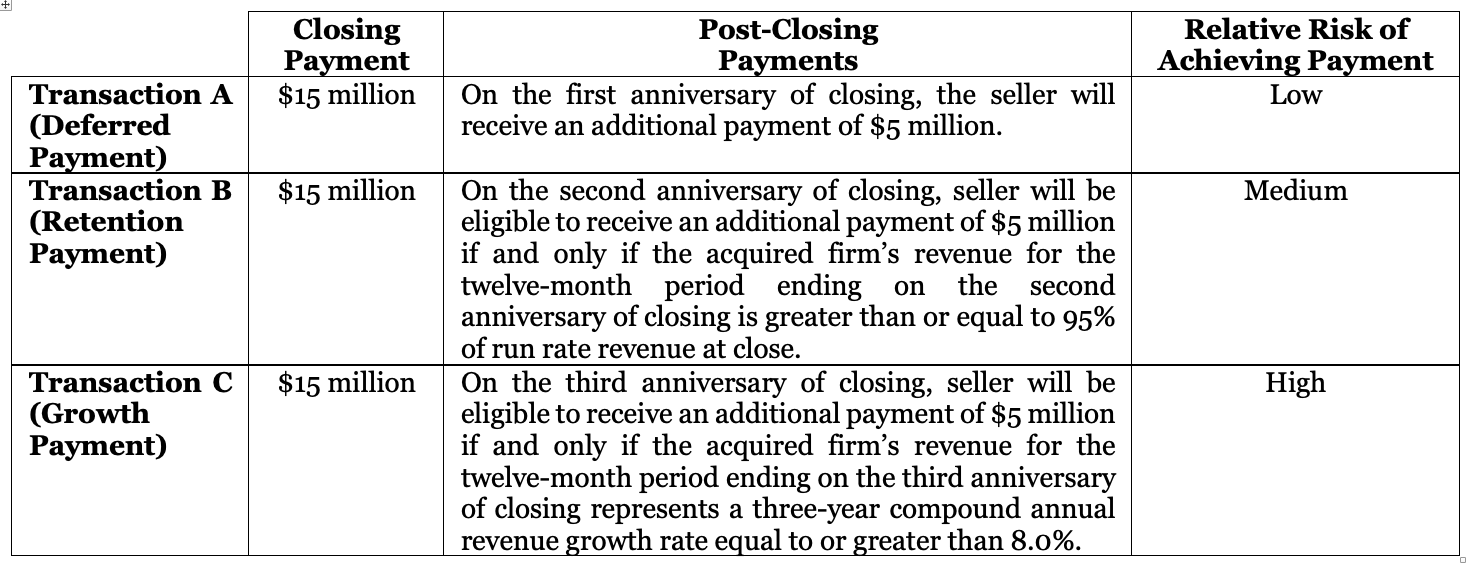

Consider the table below, which describes three transaction structures designed to illustrate different deal structure components employed in investment management transactions. In each case, we assume that the transactions occur between a willing and able buyer and a willing and able seller acting at arm’s length in an open and unrestricted market when neither is under compulsion to buy or sell and both have knowledge of relevant facts.

Click here to expand the image above

Each of the three transactions features a $15 million closing payment and potential additional consideration of $5 million, for a total possible consideration of $20 million. In Transaction A, the additional payment is simply deferred for one year, whereas in Transaction B, it is contingent on revenue retention, and in Transaction C, it is contingent on revenue growth. Transaction A offers the most certainty in terms of risk, with the additional payment contingent only on the buyer’s future creditworthiness. In Transaction B, the seller must maintain at least 95% of existing revenue into the second year post-closing. While this is a relatively low bar, assuming the firm can grow organically and benefits from the upward drift of markets, the payment is at risk if there is significant client attrition or a protracted bear market. In Transaction C, the additional payment is contingent on the acquired firm achieving sufficient net organic growth and market growth over three years in order to generate an 8% revenue CAGR.

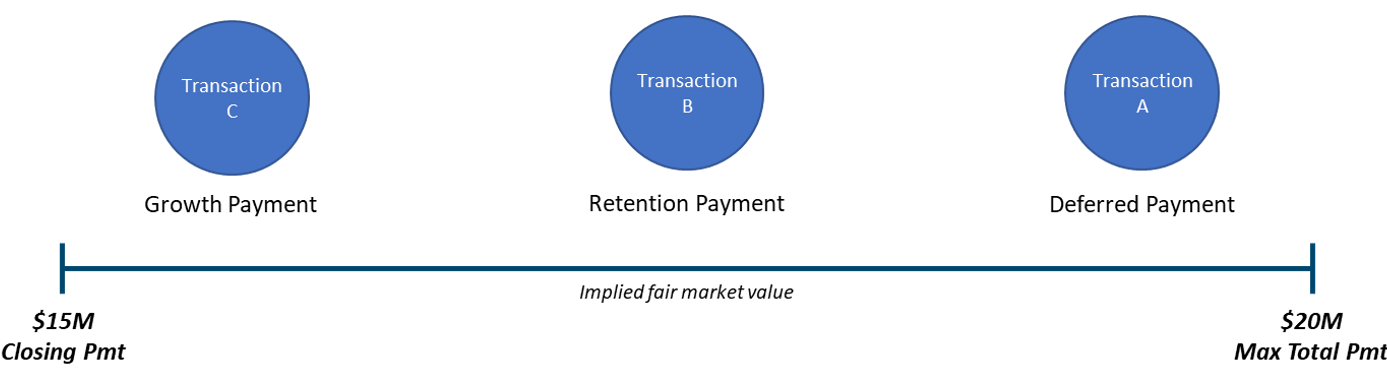

In each case, we can infer that the transaction implies a fair market value somewhere between $15 million on the low end and $20 million on the high end. To get more precise than that, it’s necessary to convert future payments into cash equivalent terms. The methods used for converting contingent consideration to a cash equivalent basis are beyond the scope of this post, but as a general rule, the riskier and farther out a payment is, the less such payment is worth on a present value, cash-equivalent basis.

The figure below illustrates directionally how the transactions compare in terms of the fair market value they imply. The most certain transaction structure (Transaction A) implies a fair market value closest to the top end of the range ($20 million) but still below due to the time value of money and buyer credit risk. The least certain structure (Transaction C) implies a fair market value closer to the bottom end of the range, given the relatively high risk of achieving the growth hurdle. Transaction B is somewhere between the other two transactions in terms of risk and timing of the payment, and as such, the implied fair market value lies between the other two.

Click here to expand the image above

When analyzing real-world transactions, it’s important to keep in mind that the headline deal values we see reported are often based on the maximum possible consideration that the seller is eligible to receive under the terms of the purchase agreement. Such headline values may not indicate fair market value to the extent that they are not expressed in terms of cash equivalents. As the example above illustrates, making reliable inferences about the fair market value implied by transactions in the industry requires a deeper dive to understand the structure of the deal. Often, the details of earnout structures are not publicly available, but real-world transactions can nevertheless be informative and serve to benchmark thinking regarding the fair market value of investment management firms, provided the transactions are subjected to a proper degree of scrutiny.