Specter of Stagflation Threatens RIAs

Time to Stop and Consider a Trifecta of Possible Headwinds for Investment Managers

Carter-era Corvette: not so fast (Mr.choppers, CC BY-SA 3.0

Higher interest rates over the past three years haven’t had much impact on RIA transaction multiples, aided by strong financial markets and some window-dressing on deal terms. As rates started to fall in 2024, we saw the possibility of further support for transaction activity throughout the investment management community. The political and economic environment of early 2025 seems to be pointing to a new risk not seen since the late 1970s, and it isn’t too early for leadership at investment management firms to consider (model) what might happen if we find ourselves revisiting some of the challenges of the Carter years.

Stagflation is a term coined by British politician Ian Macleod in the 1960s to describe an economic period that simultaneously exhibits high inflation, stagnant economic growth, and elevated unemployment. It’s too early to tell if the current focus on tariffs and government austerity, layered on top of private sector weakness, will lead to stagflation in the U.S. But it’s starting to be discussed, and it isn’t too early to consider what it might mean to the RIA sector.

Unlike most things in finance, the other economic factors that accompany stagflation exacerbate the negative impact on RIAs rather than mitigating them. Higher inflation will keep the cost of financing higher, steeping the path for firms saddled with acquisition-related debt. Inflation also hits hardest on the biggest expense category for RIAs: labor. And, in all likelihood, economic headwinds and volatility in general could cut valuations in financial markets, leading to steep declines in AUM and, of course, revenue.

If you haven’t already (I imagine many of you have), this is an excellent time to stress-test your financial condition to see what impact weakened markets, higher inflation, and rising interest rates will have on your firm.

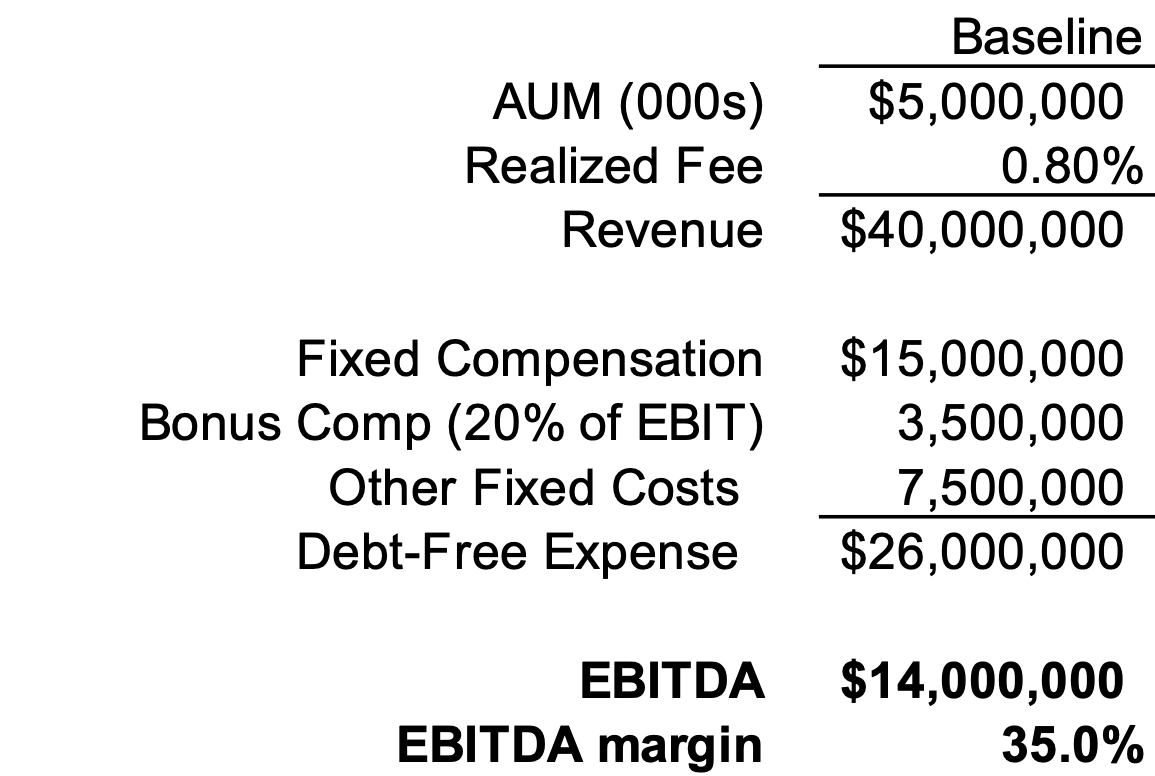

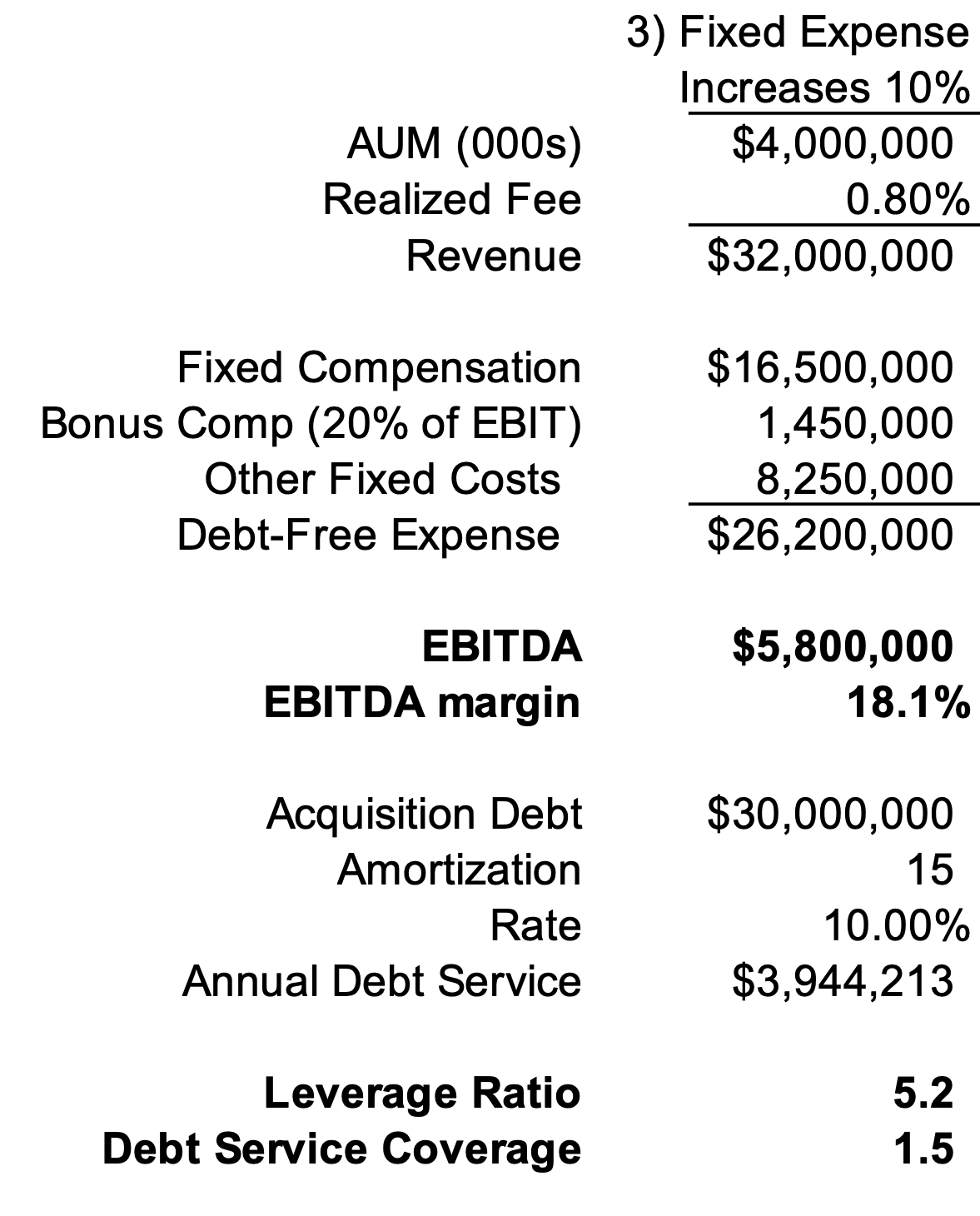

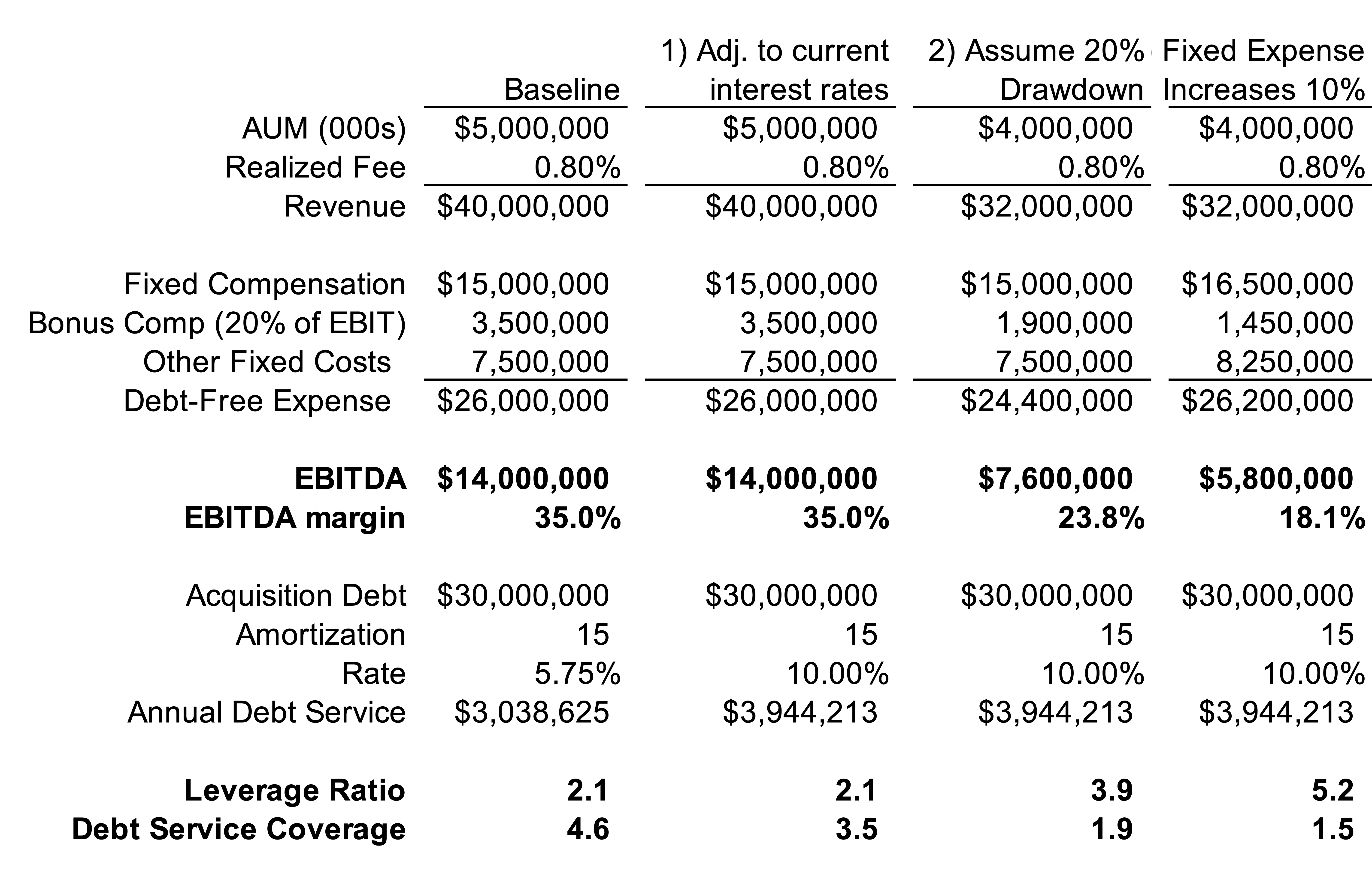

Base Case: Successful Wealth Manager

Assume a successful wealth management firm with $5 billion in AUM that generates fee revenue at a blended rate of 80 basis points. On the expense side, salaries run about $15 million, which, at 40% of revenue, is within norms. Variable — or bonus — compensation runs 20% of pre-bonus EBITDA, after consideration of non-personnel related expenses, which total 20% of revenue. The net result is an EBITDA margin of 35% — very healthy for the sector. With strong margins and a variable compensation structure that buffers some of the impact of changes in profitability, this is the profile of a firm designed to weather most RIA operating environments.

Base Case Plus Debt

Now, let’s take our sample firm case one step further and assume that part of this wealth manager’s business was acquired in the ZIRP years in leveraged purchases using covenant-light financing from a non-bank lender. Acquisition debt outstanding is $30 million, amortizing over 15 years at a base rate plus 550 basis points, or 5.75% in the ZIRP years. This computes to annual debt service of about $3.0 million, no sweat for a firm with so much debt-carrying capacity.

Under the circumstances described in our base case, debt is well within conventional covenants, with debt to EBITDA of 2.1x and debt service coverage (EBITDA to debt service) of more than 4x.

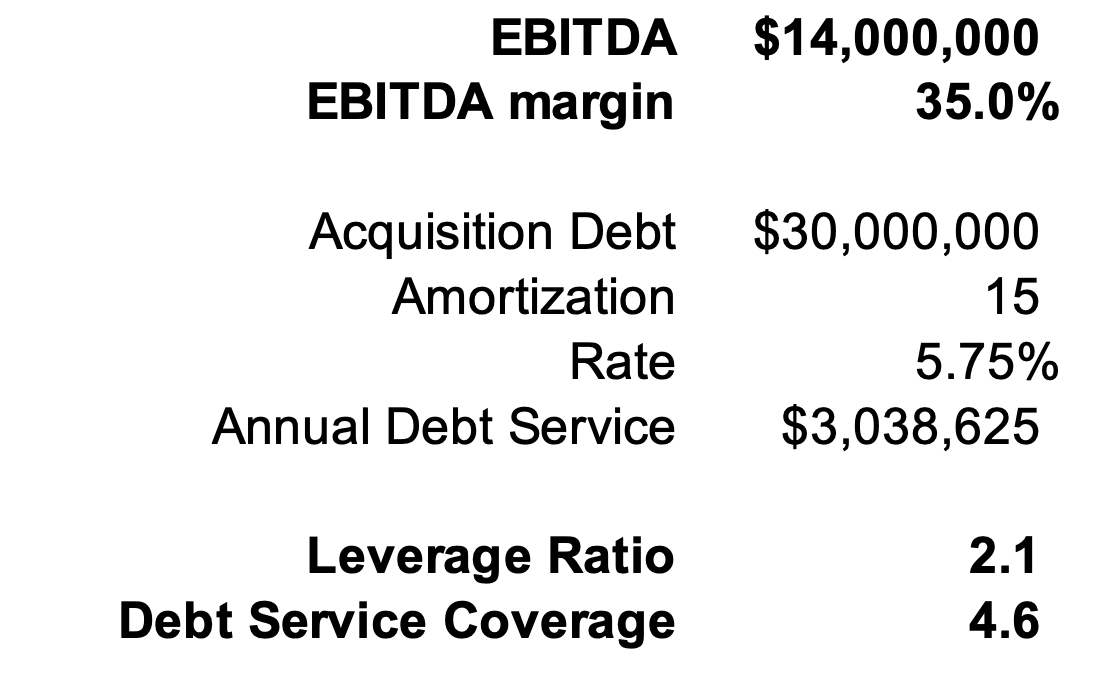

Threat 1: Higher Interest Rates

Leverage ratios that looked fine during the ZIRP years are not as good today, of course. That same premium to SOFR results in a cost of debt closer to 10% today, which significantly impacts our firm’s ability to service the debt. If rates continue to drop, this picture improves. But if inflation is sticky and rates don’t move, our firm has much less margin for error on its balance sheet.

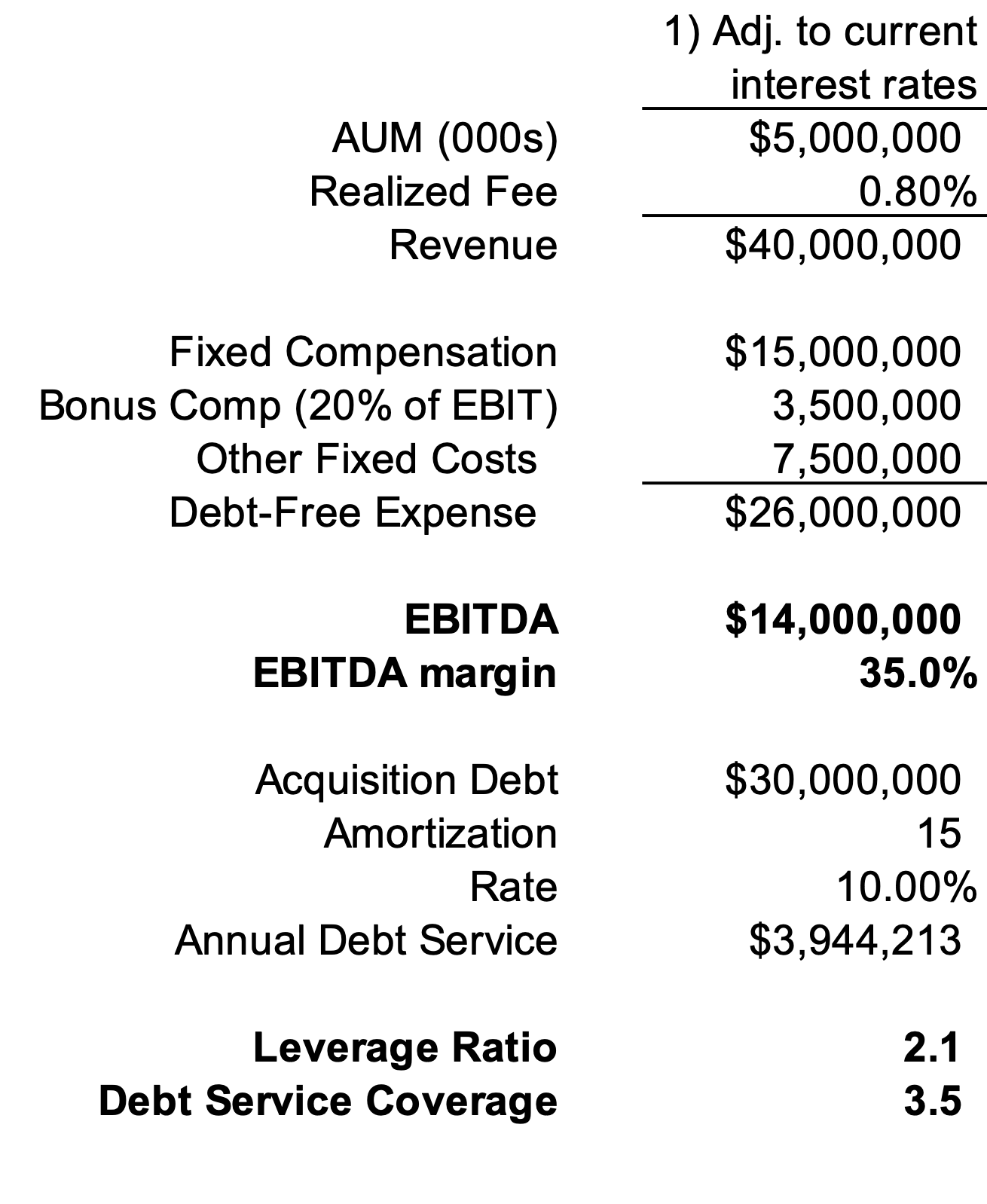

Threat 2: Impact of Bear Market

As I write this, major U.S. equity indices are off their highs, and some stocks have been hit really hard by recent volatility. We are still far from a bear market. Normally, a wealth manager could expect falling equity markets to be offset by a flight to quality. That market rotation would increase bond prices or, at least, enable them to hold steady and offset the impact on AUM from falling stocks. As we all know too well, debt markets in 2022 didn’t offer any shelter from the equity storm, and we can’t assume help from fixed income to mitigate the downturn in equity markets if inflation becomes a problem. In recent years, higher rates appear to be repricing different asset classes in such a way that we’re seeing more correlation than usual — certainly more than we would prefer.

A 20% drawdown in AUM has a corresponding impact on our sample firm’s revenue, but the only expense offset is bonus compensation. With this one change, our sample firm’s EBITDA margin declines to under 24%, and the leverage ratio nearly doubles as the debt service ratio declines.

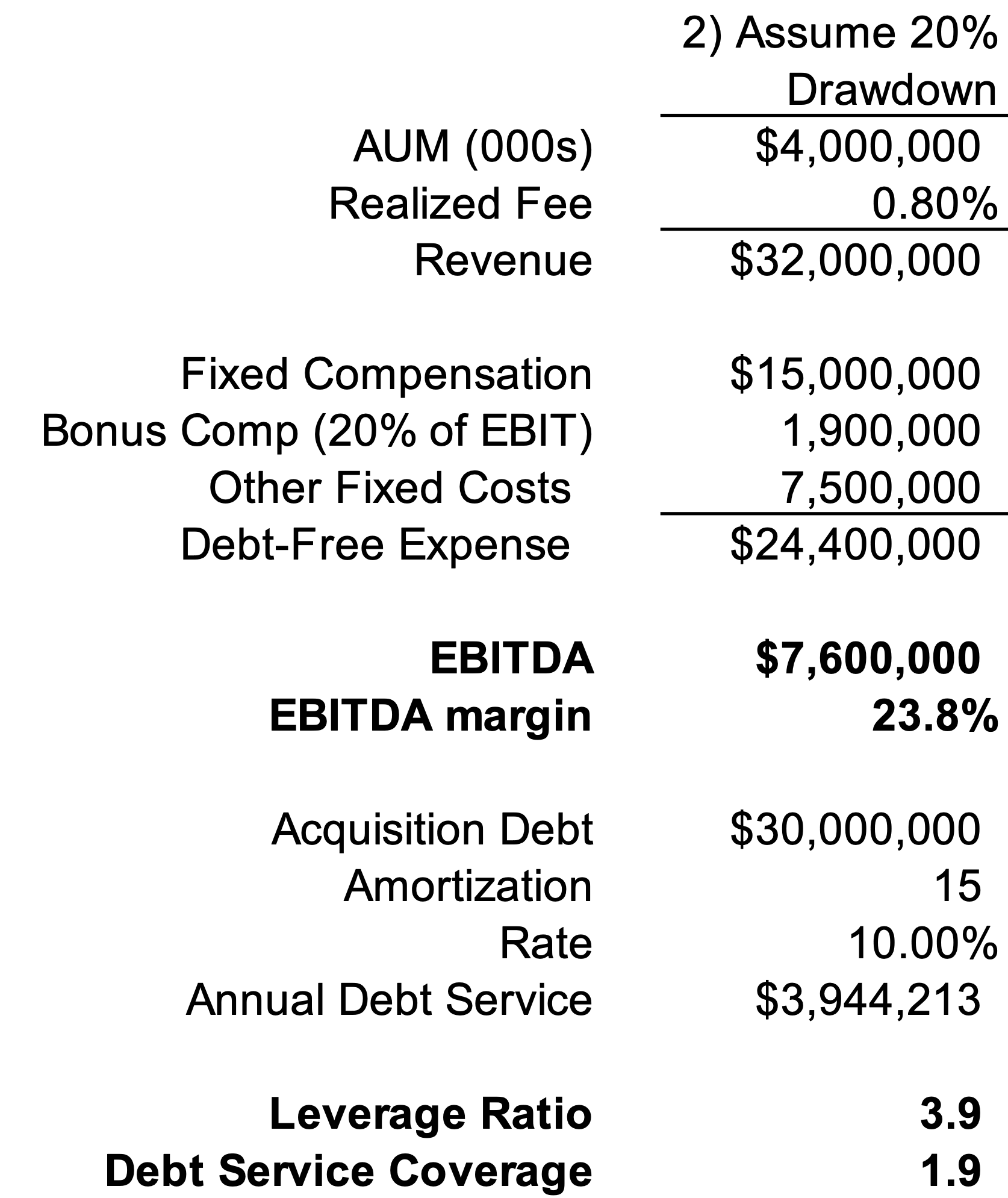

Threat 3: Inflation

If the Fed has to abandon its current downward bias on rates, it will be because inflation remains above the Fed’s target. Lots of expenses borne by RIAs are subject to inflation. The biggest expense for a wealth manager is, of course, labor — and especially so in this market because talent is scarce. The RIA industry may actually be experiencing negative unemployment, as the demand for skilled staff from client-facing to compliance positions exceeds the number of people employed in the industry. Peruse your LinkedIn, and you’ll see investment management talent playing musical chairs, all of which threatens to increase costs for everyone at something exceeding inflation. In major markets, non-staff costs like rent are back on the rise, and other costs from tech to insurance are at least keeping pace.

If we increase fixed costs by 10%, overall expenses grow considerably. Again, because of the hit to profitability, bonus compensation drops — at least in theory. Cuts in variable comp may prompt staff to look elsewhere, increasing talent replenishment costs and reducing the function of profit-sharing schemes in cushioning the blow of lower margins.

Couple inflation with the drawdown in markets and the EBITDA margin is cut even further. At this point, leverage ratios are beyond compliance levels even for non-bank lenders, and our sample company is at risk of not being able to service its debt.

If EBITDA drops when interest rates increase, what does that do to our sample firm’s ability to service its debt? Well…it doesn’t help. If the Fed reverses course and interest rates increase, which is a worrying new concern (but not yet a consensus expectation), our highly diminished EBITDA barely covers principal and interest payments.

Efforts to stave off default mostly include restructuring debt into longer amortization terms and cutting owner compensation. My stepfather often told me that you can always tell which one of a banker’s eyes is glass: it’s the one that shows sympathy.

What About You?

I was reminded this week of a few comforting words from noted British economist Elroy Dimson: “Risk means more things can happen than will happen.” Given the possibilities I’ve presented here of things that can happen, we can all hope that other things will happen. Dimson probably didn’t intend to be quoted on this matter in the spirit of optimism, but right now, it sounds better than President Jimmy Carter’s description of similar times: malaise.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights