Three Considerations for Your RIA’s Buy-Sell Agreement

Working on your RIA’s buy-sell agreement may seem like an inconvenience, but the distraction is minor compared to the disputes that can occur if your agreement isn’t structured appropriately. Crafting an agreement that functions well is a relatively easy step to promote the long-term continuity of ownership of your firm, which ultimately provides the best economic opportunity for you and your partners, employees, and clients. If you haven’t looked at your RIA’s buy-sell agreement in a while, we recommend dusting it off and reading it in conjunction with the discussion below.

Decide What’s Fair

A standard refrain from clients crafting a buy-sell agreement is that they “just want to be fair” to all the parties in the agreement. That’s easier said than done because fairness means different things to different people. The stakeholders in a buy-sell scenario at an investment management firm typically include the founding partners, subsequent generations of ownership, the business itself, non-owner employees of the business, and the clients of the firm. It is nearly impossible to be “fair” to that many different parties, considering their different motivations and perspectives.

- Clients. Client relationships are often the single most valuable asset that an asset or wealth management firm possesses, and avoiding internal disputes is crucial to maintaining these relationships. Beyond investment advice, clients pay for an enduring and trusting relationship with their investment manager. As the profession ages and ownership transitions to a new generation of management, we see a well-functioning buy-sell agreement and broader succession planning as either a competitive advantage (if done well) or a competitive disadvantage (if disregarded).

- Founding owners. Aside from wanting the highest possible price for their interest in the firm, founding partners usually want to have the flexibility to work as much or as little as they want to, for as many years as they so choose. These motivations may be in conflict with each other, as winding down one’s workload into a state of partial retirement and preserving the founding generation’s imprint on the company requires a healthy business, which in turn requires consideration of the other stakeholders in the firm.

- Subsequent generation owners. The economics of a successful investment management firm can set up a scenario where buying into the firm can be very expensive, and new partners naturally want to buy as cheaply as possible. Eventually, however, there is a symmetry of economic interests for all shareholders, and buyers will eventually become sellers. Untimely events can cause younger partners to need to sell their stock, and they don’t want to be in a position of having to give it up too cheaply.

- The firm itself. The company is at the hub of all the different stakeholder interests and is best served if ownership is a minimal distraction to the operation of the business. Since handwringing over ownership rarely generates revenue, having a functional shareholders’ agreement that reasonably provides for the interests of all stakeholders is the best-case scenario for the firm. If firm leadership understands how ownership is going to be handled now and in the future, they can be free to focus on maximizing the performance of the company while at the same time avoiding costly disputes over ownership.

- Non-owner employees. Not everyone in an investment management firm qualifies for ownership or even wants it, but all RIAs are economic eco-systems in which all employees depend on the presence of stable and predictable ownership.

The point of all this is to consider whether or not you want your buy-sell agreement to create winners and losers, and if so, be deliberate about defining who wins and who loses. Ultimately, economic interests which advantage one stakeholder will disadvantage some or all of the other stakeholders.

If the pricing mechanism in the agreement favors a relatively higher valuation, then whoever sells first gets the biggest benefit of that at the expense of the other partners and anyone buying into the firm. If pricing is too high, internal buyers may not be available, and the firm may need to be sold to perfect the agreement. At relatively low valuations, the internal transition is easier, and business continuity is more certain, but the founding generation of ownership may be perversely encouraged not to bring in new partners, stay past their optimal retirement age, or push more cash flow into the compensation instead of shareholder returns as the importance of ownership is diminished.

Recognizing and ranking the needs of the various stakeholders in an investment management firm is always a balancing act, but one which is typically best done intentionally.

Define the Standard of Value

Standard of value is an abstraction of the circumstances giving rise to a particular transaction. It imagines the type of buyer, the type of seller, their relative knowledge of the subject asset, and their motivations or compulsions. Identifying and clearly defining the standard of value in your buy-sell agreements will save time and money when triggering events occur.

Portfolio managers are familiar with certain perspectives on value, such as market value (the price at which a company’s stock trades) and intrinsic value (what they think the security is worth, based on their own valuation model). None of these standards of value are particularly applicable to buy-sell agreements, even though technically they could be. Instead, valuation professionals such as our group look at the value of a given company or interest in a company according to standards of value such as fair market value or fair value, among others.

Identifying and clearly defining the standard of value in your buy-sell agreements will save time and money when triggering events occur.

In our world, the most common standard of value is fair market value, which applies to virtually all federal and estate tax valuation matters, including charitable gifts, estate tax issues, ad valorem taxes, and other tax-related issues. It is also commonly applied in bankruptcy matters.

Fair market value has been defined in many court cases and in Internal Revenue Service Ruling 59-60. It is defined in the International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms as:

The price, expressed in terms of cash equivalents, at which property would change hands between a hypothetical willing and able buyer and a hypothetical willing and able seller, acting at arm’s length in an open and unrestricted market, when neither is under compulsion to buy or sell and when both have reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.

The benefit of the fair market value standard is familiarity in the appraisal community and the court system. It is arguably the most widely adopted standard of value, and for a myriad of buy-sell transaction scenarios, the perspective of disinterested parties engaging in an exchange of cash and securities for rational financial reasons fairly considers the interests of everyone involved.

For most buy-sell agreements, we would recommend one of the more common definitions of fair market value.

The standard of value is critical to defining the parameters of a valuation. We would suggest buy-sell agreements should name the standard and cite specifically which definition is applicable. The downsides of an ambiguous or home-brewed definition can be severe. For most buy-sell agreements, we would recommend one of the more common definitions of fair market value.The advantage of naming fair market value as the standard of value is that doing so invokes a lengthy history of court interpretation and professional discussion on the implications of the standard, which makes application to a given buy-sell scenario clearer.

Define the Level of Value

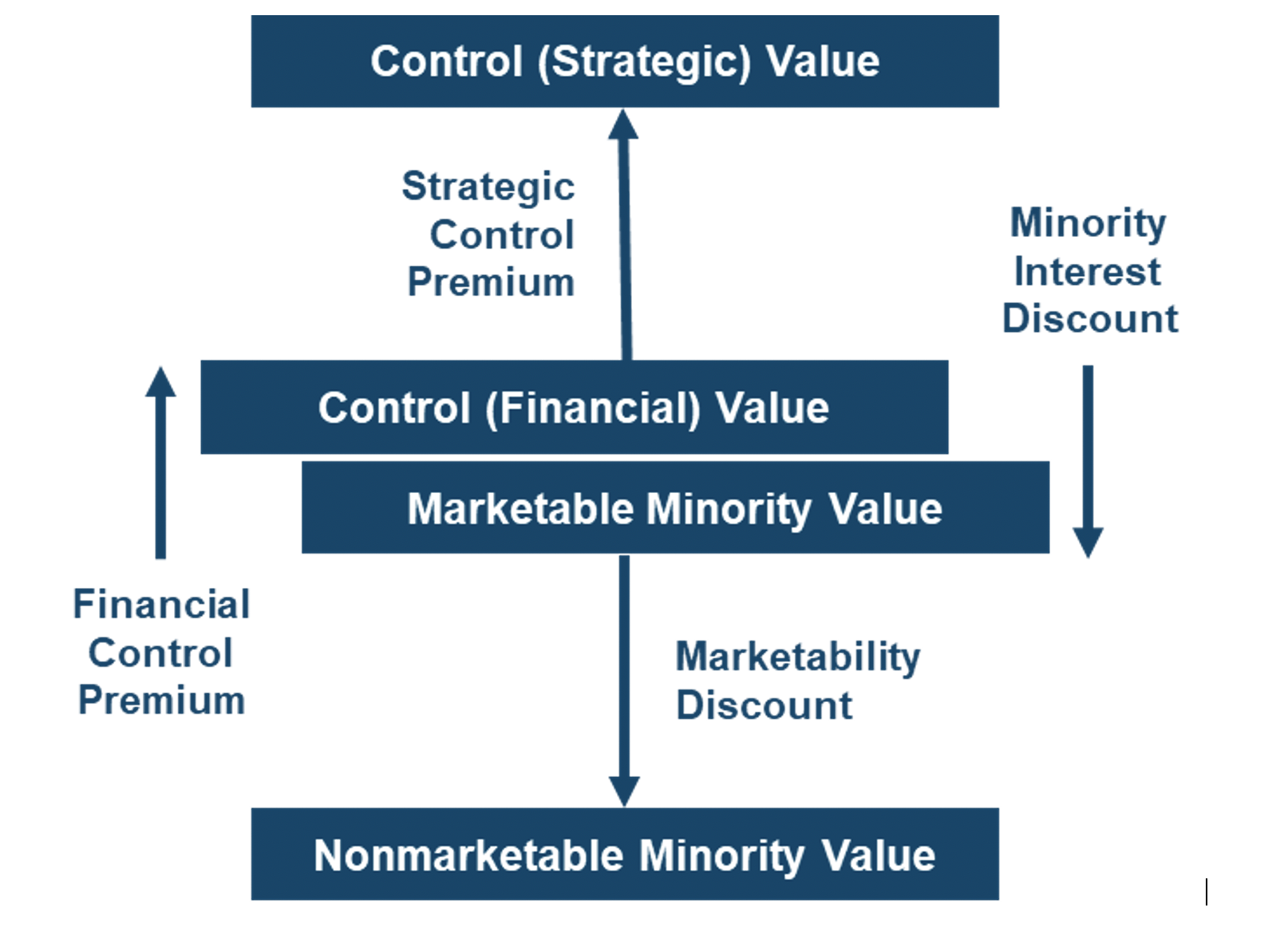

Valuation theory suggests that there are various “levels” of value applicable to a business or business ownership interest. From a practical perspective, the “level of value” determines whether any discounts or premiums are applied to a baseline marketable minority level of value. Given the potential for valuation disputes regarding the appropriate level of value, buy-sell agreements function best when they memorialize the parties’ understanding of what level of value will be used in advance of a triggering event occurring.

Most portfolio managers and financial advisors will already be familiar with the concept of “levels of value,” but they may be unfamiliar with the terminology used in the valuation profession to describe these levels. A minority position in a public company with active trading typically transacts as a pro rata participant in the cash flows of the enterprise because the present value of those cash flows is readily accessible via an organized exchange. This is known as the “marketable minority” level of value in the appraisal world. Portfolio managers usually think of value in this context until one of their positions becomes subject to acquisition in a takeover by a strategic buyer. In a change of control transaction, there is often a cash flow enhancement to the buyer and/or seller via combination, such that the buyer can offer more value to the shareholders of the target company than the market grants on a stand-alone basis. The difference between the publicly traded price of the independent company and the value achieved in a strategic acquisition is commonly referred to as a control premium.

Closely held securities, like common stock interests in RIAs, don’t have active markets trading their stocks, so a given interest might be worth less than a pro rata portion of the overall enterprise. In the appraisal world, we would express that difference as a discount for lack of marketability.

Sellers will, of course, want to be bought out pursuant to a buy-sell agreement at their pro rata enterprise value. Buyers might want to purchase at a discount (until they consider the level of value at which they will ultimately be bought out). In any event, the buy-sell agreement should consider the economic implications to the investment management firm and specify what level of value is appropriate for the buy-sell agreement.

Fairness is a consideration here, as is the sustainability of the firm. If a transaction occurs at a premium or a discount to pro rata enterprise value, there will be “winners” and “losers” in the transaction. This may be appropriate in some circumstances, but in most investment management firms, the owners joined together at arms’ length to create and operate the enterprise and want to be paid based on their pro rata ownership in that enterprise. That works well for the founders’ generation, but often the transition to a younger and less economically secure group of employees is difficult at a full enterprise-level valuation.

In any event, the buy-sell agreement should consider the economic implications to the investment management firm and specify what level of value is appropriate for the buy-sell agreement.

Further, younger employees may not be able to get comfortable with buying a minority interest in a closely held business at a valuation that approaches change of control pricing. Typically, there is often a bid/ask spread between generations of ownership that has to be bridged in the buy-sell agreement, but how best to do it is situation-specific. Whatever the case, the shareholder agreement needs to be very specific as to the level of value.

Does the pricing mechanism create winners and losers? Should value be exchanged based on a control level valuation that considers buyer-seller specific synergies, or not? Should the pricing mechanism be based on a value that considers valuation discounts for lack of control or impaired marketability? Exiting shareholders want to be paid more and continuing shareholders want to pay less, obviously. What’s not obvious at the time of drafting a buy-sell agreement is who will be exiting and who will be continuing.

There may be a legitimate argument to having a pricing mechanism that discounts shares redeemed from exiting shareholders, as this reduces the burden on the firm or remaining partners and thus promotes the firm’s continuity. If exit pricing is depressed to the point of being punitive, the other shareholders have a perverse incentive to retain their ownership longer and force out other shareholders artificially. As for buying out shareholders at a premium value, the only argument for “paying too much” is to provide a windfall for former shareholders, which is even more difficult to defend operationally. Still, all buyers eventually become sellers, so the pricing mechanism has to be durable for the life of the firm.

Conclusion

Keeping the above considerations in mind when drafting or updating your buy-sell agreement will help create a document that promotes the sustainability and orderly ownership transition of the firm while balancing the interests of the firm’s various stakeholders and the firm itself. However, this is far from an exhaustive list of things to consider when constructing your buy-sell agreement. In next week’s post, we’ll discuss additional parameters that should be addressed when constructing your buy-sell agreement.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights