Ignoring the Obvious: What the Market isn’t Telling us About RIA Valuations

1959 Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud Drophead Coupe that sold for $445,000 at R.M. Sotheby’s auction in Amelia Island in March. Overall, the classic car market is mixed – as some think it should be. Image by Karissa Hosek (R.M. Sotheby's)

Classic car collecting has probably reached its apex, with stories touting old iron as an alt-investment and giving tips for beginners to the space. Have muscle cars finished their run? Are 90s cars next to rise? Are Ferraris and Porsches on the downslope? And so forth. The chatter is interesting but mostly misses the point. Collecting old cars is about nostalgia and stories and traveling to auctions in beautiful locations and very occasionally about making money. About the only thing you can guarantee by investing in classic cars is that it is cheaper than owning horses.

Private Markets for RIAs Have Diverged from the Public Markets

Over the weekend, the Financial Times published an article touting the rising merger and acquisition activity in the U.S. wealth management industry. The piece echoed much of the typical commentary on the RIA industry’s prospects for deal activity: a large, profitable, but fragmented community of firms needing scale to develop the necessary technology infrastructure and serve sophisticated client needs. The article talked to leaders in several PE-backed consolidators and some M&A specialists in the space, all of whom talked their book in general agreement that valuations were strong and consolidation was on. What the article didn’t address is that while private equity has indeed been actively pursuing the investment management industry, the public markets seem to have lost interest.

What Goes Down, Can Go Down Further

It’s not rocket science: strong fundamentals plus weak pricing equals a buying opportunity.

Last July, Barron’s ran an article talking up the investment management industry that looked at six firms with depressed valuations and strongly suggested there was a lot of upside there for the taking. I’ll admit that I nodded my head in agreement, because many publicly traded investment management firms had double-digit losses, and we knew from talking to our clients that business was actually pretty good. It’s not rocket science: strong fundamentals plus weak pricing equals a buying opportunity.

Fortunately, I didn’t execute on the idea. In the nine months since the article came out, valuations for this group have generally declined further, with four of the six names covered in the Barron’s piece down even more (Legg Mason and Franklin Resources are up, barely).

Public RIA Multiples are Following the Trend Lower

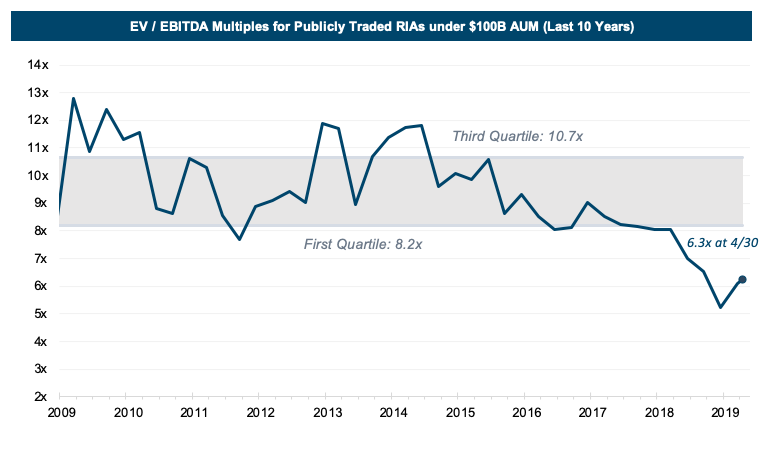

One of my colleagues at Mercer Capital, Zach Milam, has been keeping an eye on EBITDA multiples for smaller money managers. He updated the chart below through the end of April.

The chart mimics what we’re seeing in the pricing of public investment management houses. Most of the time over the past ten years, money managers traded at high single-digit or low double-digit multiples of EBITDA – a metric that should not surprise anyone. But last year the group took a nosedive toward the mid-single digits. Valuations bounced back a bit in the first part of 2019, but it’s hard to say they’ve truly recovered, despite record highs being set by many major equity indices and bond prices firming. Given the improvement in pre-tax returns yielded by the late 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, this down leg in EBITDA multiples is alarming.

When the Trend is NOT Your Friend

Even Warren Buffett is not having much luck with investors, having spent this last weekend facing down questions about the pace of Berkshire Hathaway’s succession planning and why the company has underperformed the S&P 500 over the past decade. And as I wrap up drafting this, the market is generally reeling from the renewed threat of tariffs on China. Whether you believe Buffett’s difficulties are isolated, part of a broader transformation in investment management, or a contra-indicator, it’s a tough time to be an active manager.

So What Explains the “Red Hot” M&A Pace?

What would M&A activity look like if a few of the major consolidators were not pursuing a landgrab strategy?

In contrast to the headlines, first quarter M&A activity should probably be characterized as “normal.” DeVoe’s first quarter transaction review shows 31 transactions, down one from the same quarter last year, and with the average size of the deal (sellers reporting just over $600 million in AUM) well down from last year. The trend in deal size has fallen consistently since 2016, and one wonders what it would look like if a few of the major consolidators, like Focus Financial, were not pursuing a landgrab strategy.

The push from the private equity backed rollups has definitely improved liquidity opportunities for sub-$1 billion RIAs, but we suspect that opportunities for larger firms are mostly unchanged. Wealth management firms and independent trust companies have many options, whereas buyers of asset management firms are more selective.

Epilogue

If you missed the article last week in the Wall Street Journal on Charles Schwab’s ascent, mostly at the expense of wirehouse firms, go read it now. Just as discount brokers revolutionized the retail investment industry and indexing took on asset management, a myriad of forces are trying to figure out how to capture what are perceived to be outsized profits in the wealth management space. There’s no Schwab-like trend in place yet, even though everyone is trying to claim there is.

For all the talk, the deal volume of the consolidators trumpeted in all the headlines is a drop in the ocean compared to the number of RIAs and the assets they manage. So far, the model of an independent firm with five to fifty employees billing 100 basis points to manage the investible wealth of mass-market millionaires is proving to be highly resilient. Many of the trends supposedly driving consolidation, like technology, make independence more sustainable. And while some smaller RIAs are joining industry roll-ups, other wealth management groups are fleeing wirehouses to go independent. In the end, it’s business as usual.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights