Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder

Drivers of Valuation in Wealth Management M&A

Fidelity recently published a study on M&A activity in the wealth management industry highlighting sellers’ ambitious expectations of the value of their firms. Fidelity found that sellers today expect EBITDA multiples of between 8x and 10x, even though median deal multiples “are still reasonably close to where they were over the five-year period between 2012 and 2017” – around 5x. What is causing the discrepancy? Sellers often focus on “exceptional, highly publicized transaction multiples.”

Over the last year, some mergers and acquisitions in the RIA space have touted impressive deal valuations, which many media outlets have highlighted. Echelon Partner’s RIA M&A Deal Report features “deals and dealmakers of the year” with estimated transaction multiples of 8x to 22x EBITDA. The deal sizes, however, ranged from $600 million to $26 billion. By contrast, roughly two-thirds of registered investment advisors have under $100 million in AUM.

There is typically more information available about these larger transactions than for the sale of a $100 million manager. 5.0x EBITDA doesn’t make as compelling a headline as 18x EBITDA. But the valuation multiples shown above are by no means normal. Most smaller deals go unreported, which results in inflated averages for reported deal valuations and inflated expectations for sale prices.

Additionally, reported deal values often include a contingent consideration which may never be fully realized. An excerpt from our whitepaper on The Role of Earnouts in Investment Management M&A illustrates how this can impact seller expectations.

ACME Private Buys Fictional Financial

On January 1, 20xx, ACME Private Capital announces it has agreed to purchase Fictional Financial, a wealth management firm with 50 advisors and $4.0 billion in AUM. Word gets out that ACME paid over $100 million for Fictional, including contingent consideration. The RIA community dives into the deal, figures Fictional earns a 25% to 30% margin on a fee schedule that is close to but not quite 100 basis points of AUM, and declares that ACME paid at least 10x EBITDA. A double-digit multiple brings other potential deals to ACME and crowns the sellers at Fictional as “shrewd.” Headlines are divided as to whether Fictional was “well sold” or that ACME was showing “real commitment” to the wealth management space, but either way the deal is lauded. The rest of the investment management world assume their firm is at least as good as Fictional, so they’re probably worth 12x EBITDA. To the outside world, everybody associated with the deal is happy.

The reality is not quite so sanguine. ACME structures the deal to pay half of the transaction value up front with the rest to be paid based on profit growth at Fictional Financial in a three year earn-out. Disagreements after the deal closes cause a group of advisors to leave Fictional, and a market downturn further cuts into AUM. The inherent operating leverage of investment management causes profits to sink faster than revenue, and only one third of the earn-out is ultimately paid. In the end, Fictional Financial sold for about 6.5x EBITDA, much less than what the selling partners wanted for the business. Other potential acquisition targets are disappointed when ACME, stung with disappointment from the Fictional transaction, is not willing to offer them a double-digit multiple. ACME thought they had a platform opportunity in Fictional, but it turns out to be more of an investment cul-de-sac.

The market doesn’t realize what went wrong, and ACME doesn’t publish Fictional’s financial performance. Ironically, the deal announcement sets the precedent for interpretation of the transaction, and industry observers and valuation analysts build an expectation that wealth management practices are worth about 10x EBITDA, because that’s what they believe ACME paid for Fictional Financial.

The example above supports Fidelity’s conclusion: sellers of investment management firms often “don’t entirely understand what drives valuation.” RIA transaction data is haphazard at best. It’s no wonder why seller’s expectations are inflated if they look only to media sources to understand valuation. In this post we hope to provide insight to the owners of wealth management firms on how likely buyers value their firm.

Cash Flow, Growth, and Risk

Valuation firms think of value as a function of cash flow, growth, and risk (or cash flow times a multiple).

Sustainable Cash Flow

The first part of the equation is simple. Higher cash flow (or EBITDA) implies a higher price tag. But margins have to be real. Disguising partner compensation as distributions to inflate profitability won’t sell, as buyers are typically sophisticated enough to know there will be a replacement cost for selling partners who retire and want to hand over their responsibilities to someone new. Low margins are a more obvious red flag, as heavy overhead is difficult to scale down and makes firms vulnerable in down markets.

So, margin has most value within what a buyer considers to be a normal range. Fidelity reported the “median operating margin of firms/deals in the past two years was 28%, with respondents saying the ranges for operating margins fell typically between 20 to <30% on the lower end, and between 30 to <40% in the upper end.”

There is more mystery involved in the multiple, but it ultimately depends on the growth trajectory and risk profile of your company. The multiple (and thus the firm’s value) is positively correlated to expected growth and inversely related to risk.

Meaningful Growth

All else equal, a buyer will pay more for an investment manager that is expected to double assets under management in five years, than one in which AUM is expected to double in ten. Higher growth implies higher future cash flows.

Over the past year, AUM at most wealth managers increased significantly as markets surged. However, AUM growth that is entirely a consequence of market activity is not sustainable over the long run. Investment performance does impact value, but buyers of wealth managers view growth in terms of net positive inflows of assets. Growth driven by market conditions brings short term increases in cash flow. But growth driven by a new marketing strategy, increased market share driven by a failing local competitor, or a new investment strategy drives long term value.

Manageable Risk

A buyer will pay more if the future cash flows are relatively certain but less if there is significant risk that your cash flow could deteriorate post acquisition.

In general, there is more risk associated with smaller companies. Small investment managers typically have a more concentrated client base, are more dependent upon key individuals to generate business, and have less developed marketing and technology infrastructure to support and grow their business.

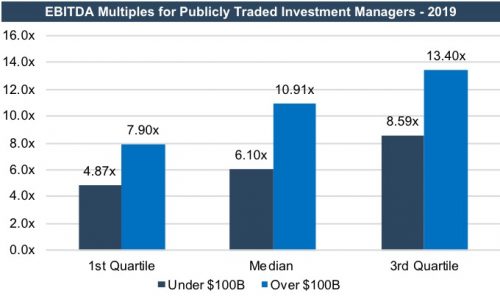

This size/value relationship even exists in firms with much larger scale than the typical RIA. Looking at the implied valuation multiples of publicly traded investment managers, the multiples of managers with under $100 billion of AUM are generally lower than those of investment managers with over $100 billion in assets.

This is why highly publicized deal multiples of massive investment managers don’t serve as a reliable benchmark for your firm.

Unfortunately, most of the risks outlined above are only truly solved with scale. Customer concentrations are reduced with more assets. Key man dependencies are lessened by hiring well-trained investment processionals (which is expensive) or by training younger professionals (which takes time). Investments in scalable technology are often too costly for small managers. However, formalizing investment processes and establishing a succession plan with a proper buy-sell agreement can reduce the risk of cash flows deteriorating if key individuals depart post acquisition.

What Will a Buyer Pay for Your Firm?

Unfortunately, there is not a simple formula to value your firm.

A highly concentrated client base may overshadow the high growth potential of your firm. On the other hand, a stable client base, with a higher probability of recurring revenue, can raise your valuation despite mediocre growth prospects.

Many business owners suffer from familiarity bias and the so-called “endowment effect” of ascribing more value to their business than what it is actually worth simply because it is well-known to them or because it is worth more to them simply because it is already in their possession. In any event, just as physicians are cautioned not to self-medicate, and attorneys not to represent themselves, so too should professional investment advisors avoid trying to be their own appraiser.

The first step of any transaction should be to obtain a valuation to establish decision-making baselines and to set transaction expectations. Mercer Capital’s Investment Management team provides asset managers, wealth managers, and independent trust companies with business valuation and financial advisory services. Call us today to discuss your valuation needs in confidence.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights