The Anatomy of a Wealth Management Firm

A Closer Look at a Business that Continues to Pivot with Client Needs

From Broker to Advisor

Wealth management firms represent a critical link between asset management firms (who develop investment products) and the highly fragmented retail client channel. The dominant model by which the wealth management industry connects retail clients with asset managers has changed significantly over the last several decades. The predecessor to the modern-day financial advisor is the wirehouse stock broker who rose to prominence during the bull market run of the 1980s and 90s. Typically compensated on a commission basis, the broker was as incentivized to churn client assets as he was to grow them because pay was tied to transactions rather than performance – at least directly. The result was often a gradual transfer of wealth from the customer to the broker, whose interest ran counter to most investors. Oversight was minimal, and many regulators were not properly incentivized themselves. Change was desperately needed.

Fortunately, the business has come a long way since the Wolf of Wall Street days. Evolving client expectations, increased transparency, and stronger fiduciary standards have expedited the broker-to-advisor conversion in recent years. Brokerage houses fueled by commissions have largely been replaced by wealth management firms whose fee schedules vary with client assets instead of trades executed on their behalf. A financial advisor’s office now bears more resemblance to a law firm than Stratton Oakmont or Gekko and Co. The industry has definitely become more boring, which is good news for those in need of competent financial advice.

This evolution has had some obvious benefits for advisors as well. Client attrition rates have plummeted since the broker days as customers are far more likely to stick around when their advisor’s interests are aligned with their own. High retention rates make it easier to retain the employees who service these accounts, enabling partners to build an actual business rather than a collection of brokers that switches firms every few years.

Recurring revenue from asset-based fees is also more predictable than commission income. A wealth management firm’s ongoing or run-rate revenue is simply the product of its current AUM balance and effective realized fee percentage. This predictability makes it easier to forecast hiring needs and project future levels of profitability. These apparent financial advantages combined with the fact that the fee-based model is more appealing to clients explains why the number of broker-dealer firms has declined 24% over the last decade, while the number of RIAs has grown by over 20% just in the last five years, according to FINRA and the SEC. Asset flows also demonstrate the apparent advantages of the fee-based, fiduciary model; RIAs as a group are growing AUM at a faster rate than other distribution channels and manage a growing share of total AUM. Look for these trends to continue as investors become more educated on fee structures while regulators crack down on conflicts of interest and suitability concerns.

Characteristics of Today’s Wealth Management Firm

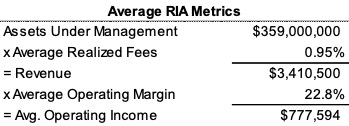

According to ThinkAdvior and a report from Investment Advisor Association (IAA), the typical (i.e. average) SEC-registered investment advisor has the following characteristics:

- Works with a team of nine employees

- Has $359 million in regulatory assets under management

- Manages 124 client accounts

- Has at least one pension/profit-sharing plan as a client

- Exercises discretionary authority over most accounts

- Does not have actual physical custody of client assets or securities

- Is organized as a U.S.-based limited liability company headquartered in California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, or Texas

Even though some of the firms included in the report outlined above are not wealth managers, they are generally representative of the wealth management industry since 94% of their clients are individuals rather than institutions. The report also states that over 95% of RIAs are compensated as a percentage of AUM while just under 4% charge commissions, so it doesn’t include many broker-dealers or RIA/BD hybrids. Perhaps also in contrast to the Wall Street era, 86% of RIAs reported no disciplinary history at all.

The IAA report also states that 57% of RIAs are “small businesses,” employing ten or fewer non-clerical employees, with 88% employing less than 50 people. Unfortunately, this end of the size spectrum is not gaining market share relative to their larger counterparts. The report found that RIAs with over $100 billion in AUM grew at a faster pace than smaller advisors last year both in terms of the number of firms and AUM. The benefits of scale and branding are largely to blame for this discrepancy, and it seems likely that this trend will continue into the foreseeable future.

How Does Your Wealth Management Firm Measure Up?

According to RIA in a Box’s annual survey, the average advisory fee in 2017 was 0.95%, down from 0.99% in the prior year. A little math (0.95% x $359 million) implies average annual revenue of $3.4 million. According to the InvestmentNews Advisor Compensation & Staffing Study, the average operating margin for an RIA was 22.8% in 2017, so here’s how the “typical” advisory firm P&L breaks out:

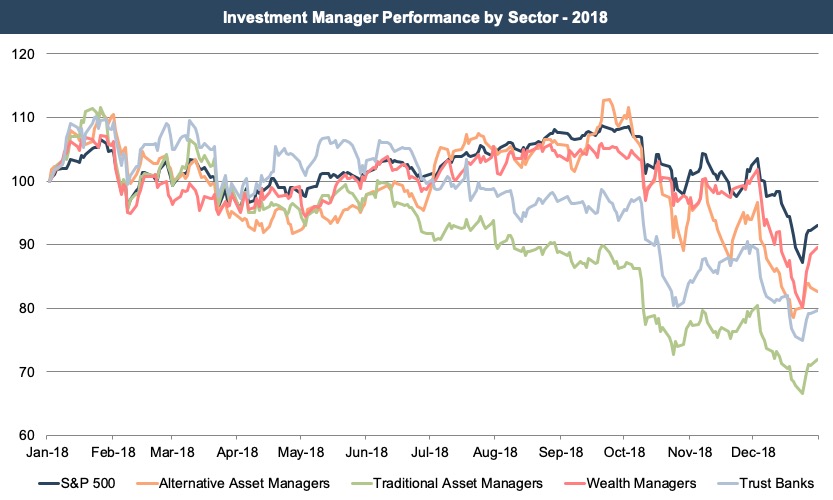

While the numbers for 2018 haven’t come out yet, we suspect they’ll be down across the board. The major indices were down 5% to 10% for the year, and realized fees have been on the skid for quite some time. Declining AUM and revenue combined with generally higher costs associated with rising compensation expenses means margins will likely be compressed as well. Valuations of publicly traded RIAs in 2018 echoed these concerns:

The silver lining for wealth management firms is that they (generally speaking) outperformed other classes of RIAs last year and are up so far in 2019. Their superior performance is likely attributable to a more adhesive customer base that won’t jump ship after a few quarters of poor returns. Wealth managers are also generally less susceptible to fee pressure than traditional and alternative asset managers that have struggled to justify their higher rates with the rise of low-cost ETFs and other passive investment products. Wealth management and financial advisory services are primarily based on client service rather than performance relative to a benchmark, so these firms have been able to stave off fee pressure and client attrition for the most part. The ability to keep this up will likely depend on their capacity to continue servicing clients while connecting with their next generation. It’s a tall order, but most wealth managers have learned to cope with this reality for quite some time. We suspect they’ll continue to do so.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights