WeInvest?

The Best Business Model in the RIA Industry Depends Not on Who You Ask, but Who’s Asking

Ford v Ferrari: Bruce McLaren’s Ford GT40 crosses the line at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, 1966 (Motorsport Magazine)

Earlier this month we had the pleasure of participating in a panel discussion on the value of wealth management firms in a transaction setting for the CFA Society of New York. In conversation after the event, one of the audience members asked me what I thought was the most successful business model to follow in the wealth management space. It’s a question we hear fairly often, and I try to avoid punting on the answer and saying “it depends.” In reality, though, it does depend.

Because I don’t care about movies made about comic book characters, I don’t see many movies these days. Next month is the release of a movie I can’t wait to see, however. “Ford v Ferrari” is based on the true story of Ford Motor Company’s failed attempt to buy Ferrari in 1963. Discussions broke down when Enzo Ferrari realized that Ford expected the transaction to include Scuderia Ferrari, his racing team, and not just the road car manufacturer. Enzo’s business might have been selling cars, but his persona was racing cars. Scuderia Ferrari was not for sale. Henry Ford II was offended at having been rebuffed, and he vowed to build a car to end Ferrari’s dominance at the annual endurance races at Le Mans. The result was a grudge match at the 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans. Ford’s purpose-built car, the GT40, beat the Ferrari 330s decisively, the first win at Le Mans for an American team.

Despite the win, Ford gave up competing at Le Mans a few years later, and no longer targets Ferrari on racetracks or in the showroom. The 1966 win did foretell a Ferrari challenger, though. The winning driver was Bruce McLaren, a New Zealander whose eponymous racing and road car company is today a major rival to almost everything Ferrari does.

The Ford/Ferrari combination failed not just because of egos, but because of mismatched goals.

Back to my discussion of business models. The Ford/Ferrari combination failed not just because of egos, but because of mismatched goals: Ford was a high-volume automaker that competed as a marketing gimmick (“race on Sunday, sell on Monday”). Ferrari was a low-volume automaker that sold road cars to finance Enzo’s racing teams. Ford wanted to make money. Ferrari needed to make money. It wouldn’t have been an easy marriage.

In the investment management industry, the question of the best business model generally comes down to opinions about scalability. At the atomic level, an RIA is composed of the relationship between one advisor and one client. Building an RIA is a debate over the best way to grow the size of client relationships, the volume of client relationships, the volume of advisors, or some combination of the three. By “best” I mean finding the right balance of margin, growth, and sustainability.

I think the “best” business model is different for different people, however. Ken Fisher built a twelve-figure AUM wealth advisory company by creating a social media marketing machine to funnel mass-affluent investors into a network of highly regimented advisors. Unfortunately for him, Fisher isn’t as regimented in his own professional interactions. Nonetheless, he proved that a high-volume, homogenous, and replicable approach to investment management is both possible and profitable.

The “best” business model is different for different people.

On the other end of the spectrum, a friend of mine retired from the hedge fund industry a few years ago and is building a boutique wealth management practice that caters to the needs of successful hedge fund managers. It is the opposite of the Fisher model: low-volume, highly specialized, and difficult to replicate. I don’t think either Fisher or my friend would be interested in pursuing the other’s approach to wealth management, but they both found models that worked for them.

For some valuable extracurricular reading on this topic, don’t miss Scott Galloway’s blog post on margins, scalability and growth. Galloway’s August blog post opened the floodgates for criticism of WeWork, and is legendary in our world where frank investment analysis is all too rare.

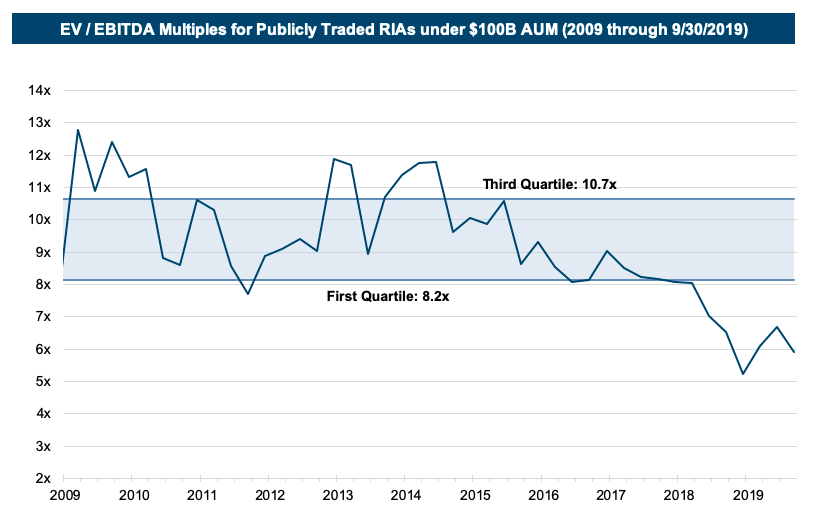

Galloway’s more recent post is a thorough and compact digression on the basics of business models and valuation. If, as he contends, the world really is shifting from a focus on growth to a focus on profitability, the investment management profession may stand to benefit in two ways: valuations should improve (much to the relief of every publicly traded RIA executive and shareholder) and value investing may finally regain its prominence (and, along with it, active management). We’ve seen “green shoots” suggesting the latter of these over the past few months in the form of an increase in active manager searches. It hasn’t shown up in public RIA share prices, though.

Galloway also offers remarks that could be interpreted as throwing cold water on consolidation efforts in the RIA space. “Services businesses (high margin) usually involve the most unpredictable and messy of inputs — people — and are dependent on relationships (also not scalable).” I don’t know if Galloway would describe certain investment management firm roll-up models as “WeInvest,” but it’s something to consider.

There may be no perfect business model, but there is a business model that’s perfect for you. The Ford v Ferrari competition today takes place on the Big Board. Globally, Ferrari sells about 8,500 cars per year, whereas Ford sells nearly twice that many cars per day. Despite the obvious scale differential, Ferrari (NYSE: RACE) sports a 50% higher earnings multiple, not to mention a 10% greater equity market cap, than Ford (NYSE: F). Advantage: Ferrari.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights