What Drives RIA Value – Growth or Margin?

More of Both Is Best, but the Tradeoff Is Measurable

1969 Series 4 Lotus Elan. Creator Colin Chapman’s dictum was “add lightness.” (Grenadille, CC BY-SA 4.0

In motor racing, winning requires building a car with the best combination of speed and handling. There’s a tradeoff between them, as speed requires bigger motors, more structure, and larger tires and brakes, all of which add weight. Weight is the enemy of handling. The physics of momentum makes it exponentially more difficult to change vector (handling) as mass increases. More speed or better handling is better. More of both is best. The optimization of this equation is Formula 1, where cars sport 1,000 horsepower but weigh less than 1800 pounds. Compare that to a three-ton, 400-horsepower Chevy Suburban, and you’ll understand why an F1 race can average 200 miles an hour (although the Suburban makes for a better Uber).

Maximizing RIA Valuations

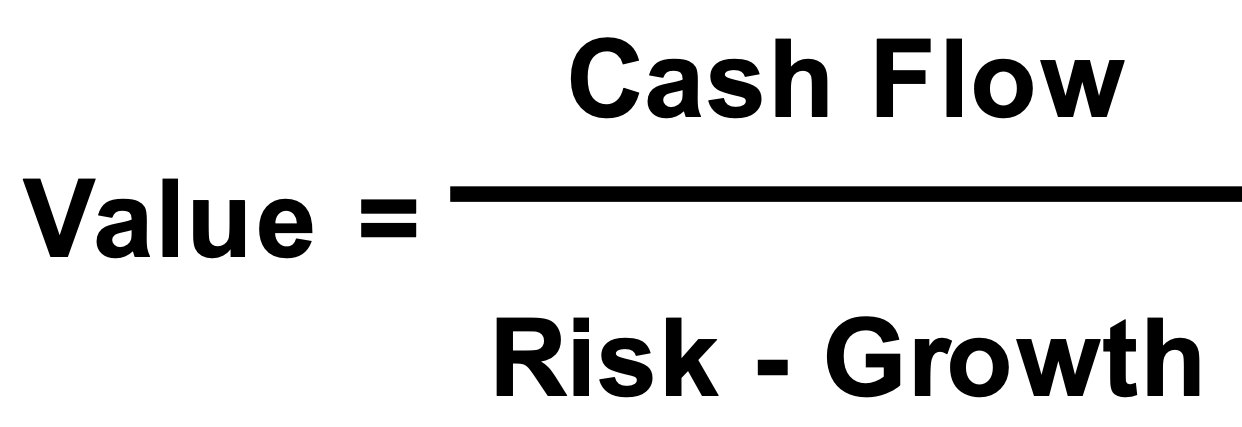

We regularly get asked how to optimize the value of an RIA. The answer is easier spread than done. Starting with the obvious, value is a function of cash flow, risk, and growth.

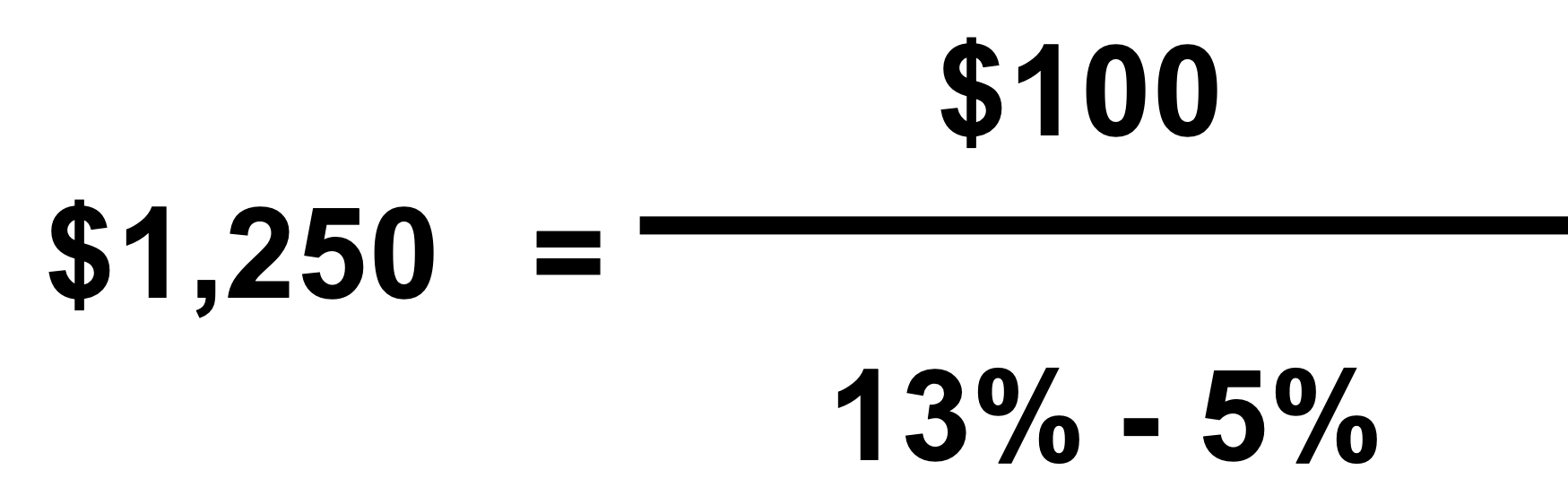

If a given RIA’s after-tax cash flow is $100, with a cost of equity of 13% and an expected growth into perpetuity of 5%, that RIA has a value of $1,250 (just add a few zeros to get actual RIA numbers).

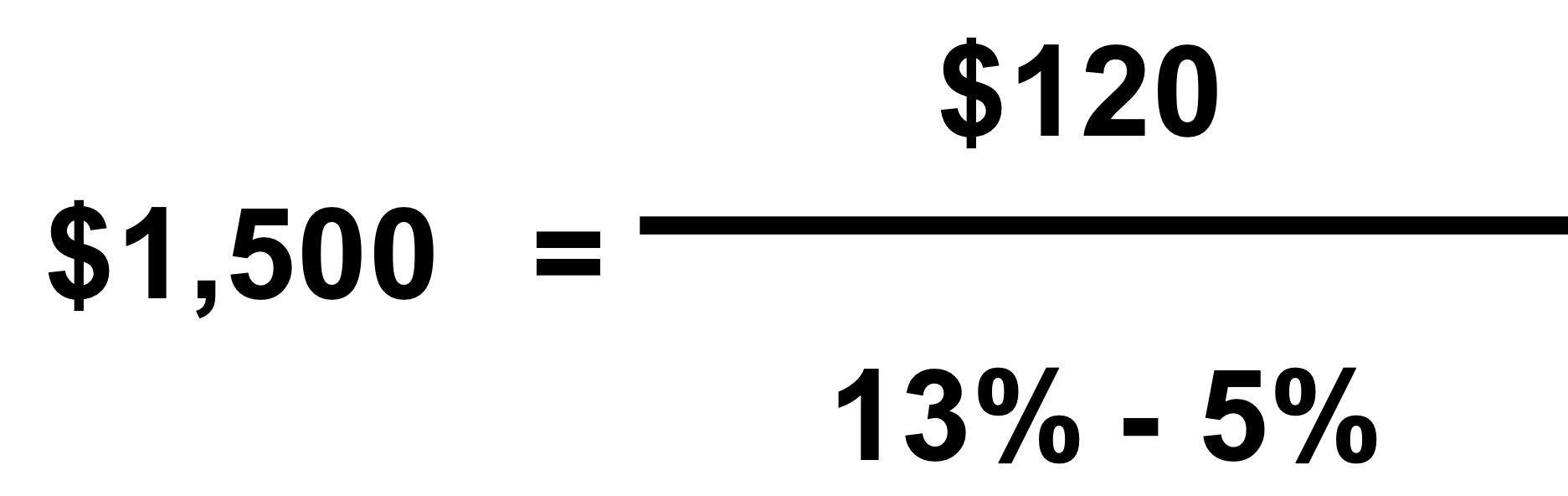

For a given cost of capital, value is a function of margin and growth. If we increase the margin of our example RIA by, say, 20%, we increase value by 20%. Simple enough.

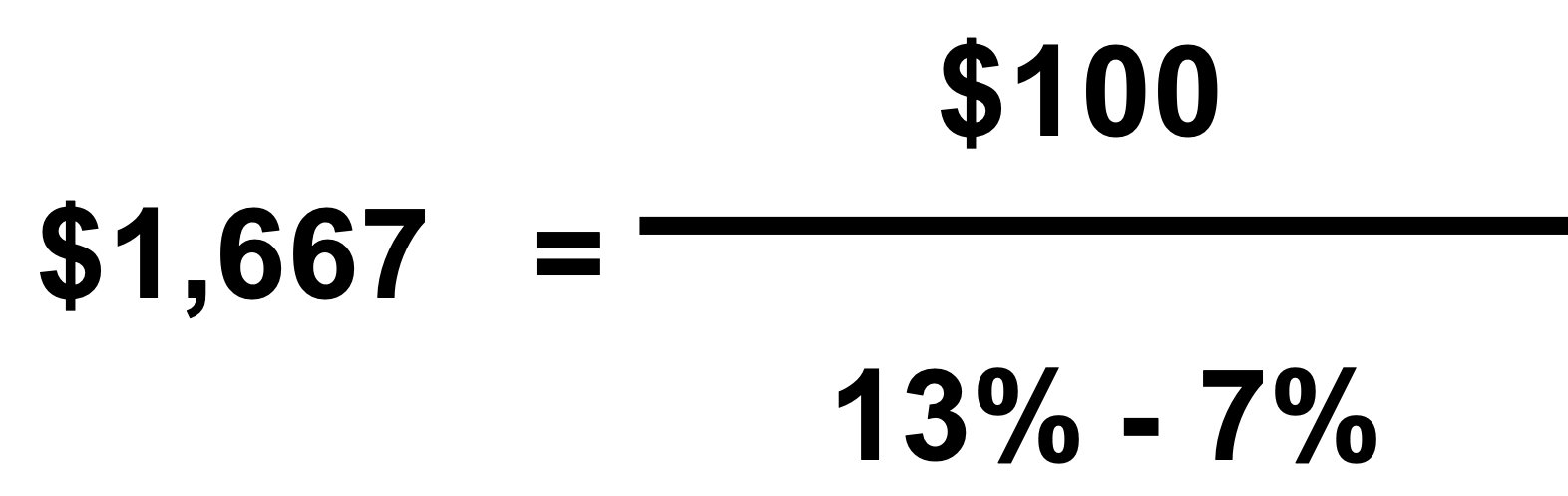

In the alternative, if we invested that extra margin in organic growth initiatives that yield an extra two percentage points of earnings growth, the impact on value is even greater. (I specify organic growth because acquisition-based growth typically requires equity transfers, which might distort this illustration.)

It’s difficult to be certain that spending money on business development efforts will result in growth. But we can be certain that not spending money on business development will not result in growth.

Margin Madness

Look back at your RIA’s performance over the past three to five years. What was your average EBITDA margin? Don’t confuse this with EBOC (earnings before owner compensation). EBITDA margins assume a reasonable level of owner/manager compensation (returns to labor) distinct from profitability (returns to capital). You may have to make some adjustments to get to a “normalized” EBITDA margin — just be mindful of what’s reasonable and what’s hoped for when making those adjustments. Our founder used to say that life is a recurring series of non-recurring expenses.

In the wealth management space, we commonly see EBITDA margins of 20% to 30%. Margins might be lower in firms structured with mostly 1099 advisors (P&Ls that more closely resemble broker-dealers) and higher in the case of ensemble practices with stringent client acceptance protocols (eschewing unprofitable client relationships). Many independent trust companies exhibit similar margin characteristics.

Margin is more variable in the case of asset management firms. Because of tremendous operating leverage, it’s not unusual for us to see EBITDA margins for asset managers above 50%. The durability of those margins is another matter.

All else equal, more margin is better. But all else is never equal because margin often comes at the expense of growth.

Growth Obsession

What are you doing with your margin? If it’s high, are you rewarding current production at the expense of the future? Are you investing in advisor recruiting and training, in marketing and business development, in missionary efforts to explore new offerings, in services to retain the next generation of clients?

Baseline growth will depend on portfolio composition, but if your wealth management firm has a client base with something resembling 60/40 portfolios designed to generate 7% per year after fees, and the spending rate for your frugal but retired client base is 2% of AUM, high retention rates will yield a market tailwind for your firm’s AUM of about 5%.

Growing beyond that 5% or so per year for a wealth management firm or independent trustco requires attracting new clients. Sometimes, new clients come from existing client referrals. Mostly, new clients come from business development efforts. Proven business development efforts can lift overall AUM growth rates to double-digit levels, but we commonly see demonstrated growth on the order of 5% to 10%. Absent operating leverage (difficult for established firms), X% in AUM growth will yield a similar increase in revenue growth and earnings growth.

As with margin, more growth is better, so long as you don’t invest so much that you’re not developing a reasonable level of current returns to equity or maintaining a margin that will cushion your firm from the impact of bear markets, major client losses, advisor defections, etc. There is also a tradeoff between margin and risk, but that’s a topic for another blog post.

Sustainable growth at asset management firms is often more difficult to derive. Asset managers with great risk-adjusted returns can bring in huge allocations of capital from institutional investors — all at once — but then your strategy hits capacity and growth is zero. Great returns can cause investors to rebalance away from you (no good deed goes unpunished). Negative alpha also runs off assets. Long-term success in asset management seems to require a balancing act of strategies (product development) and distribution channels (SMAs, mutual funds, sub-advisory relationships) that provide proven investing expertise to clients with different decision parameters. It’s not easy, but it can be highly profitable.

The “Best” RIA Business Model

A common question we get asked is what is the “best” investment management business model. I don’t have a great answer, but I think one way to define “best” is the model that provides the highest level of margin and growth with the fewest tradeoffs — the one in which the combination of margin and growth is the greatest. A 25% EBITDA margin and a 5% growth rate, totaling 30%, is perfectly respectable. But a 20% margin and 15% growth rate, totaling 35%, is better.

In the software-as-a-service space, development-stage companies are commonly rated as to their combined EBITDA and revenue growth rates, with a 40% combined rate being the hurdle that decides whether a given opportunity is investible or not. This is instructive but not entirely comparable to the RIA space. Investment management is not a development-stage idea. And the competitive forces that govern returns in mature industries like investment management will necessarily dampen opportunities for growth and margin.

In my experience, proven RIA strategies will produce at least a 30% combined margin and growth metric, and better ones will approach 40%. If “normal” growth is 5% to 10%, an EBITDA margin at or above 30% produces a combined score that pushes closer to 40%, indicating a relatively stronger business model with fewer tradeoffs between risk and growth (strong payoffs for the investment of margin in growth).

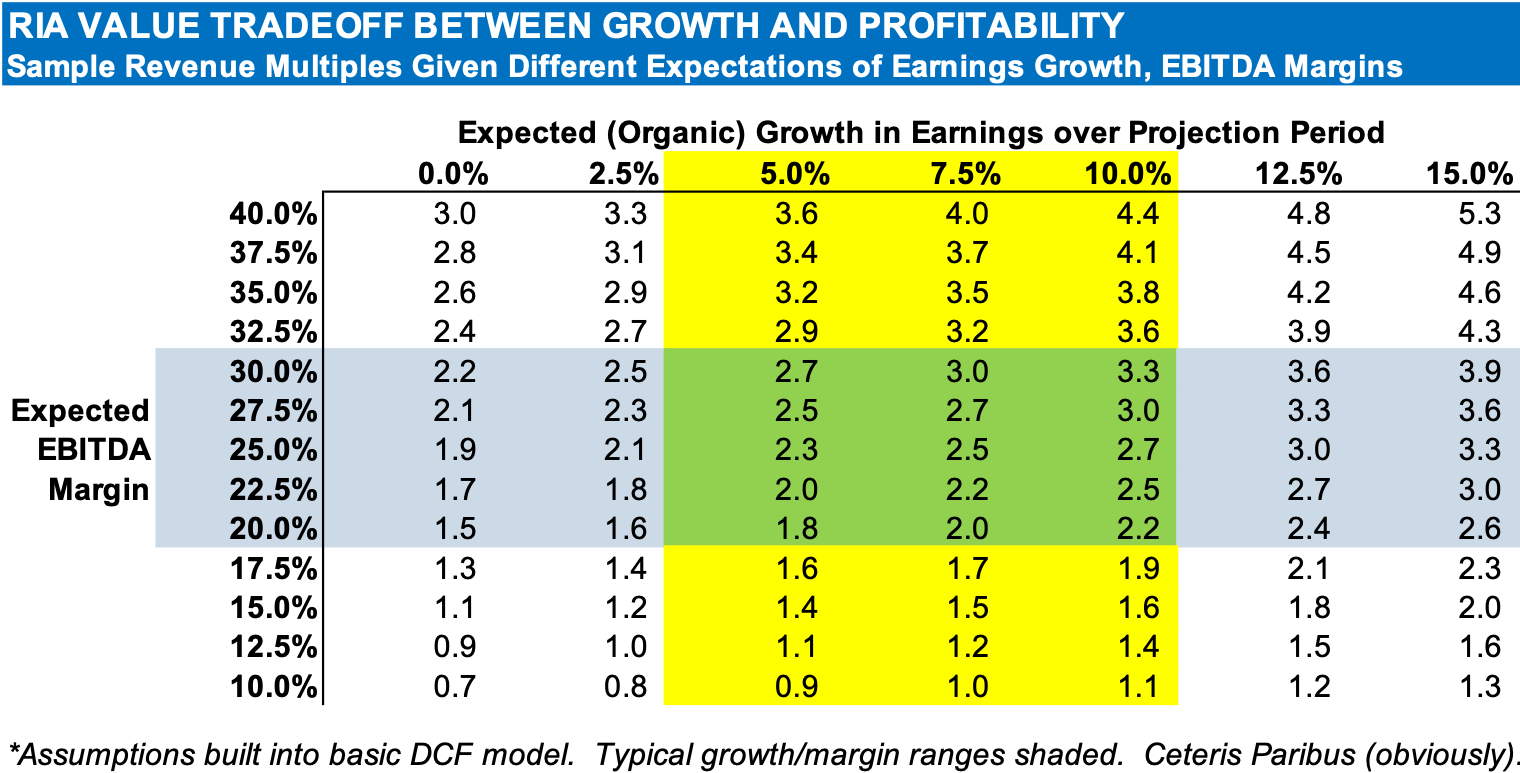

The merits of the business model will manifest in the value of the business itself. If we compare the impact of margins and growth in a discounted cash flow model, we can measure the impact of different assumptions on the implied revenue multiple of the firm (assume a debt-free RIA with a low teens cost of capital and a terminal value of 12x after-tax cash flow, five-year projection period, 12x terminal multiple).

Under the model’s assumptions, a 25% EBITDA margin and a growth expectation of 7.5% over the ten-year projection period (for a combined margin + growth score of 32.5%) results in a value of 2.5x revenue. A margin of 30% and growth of 5% (combined score of 35%) also results in a value of 2.5x revenue. But more is better. Combine a margin of 30% with expected annual earnings growth of 10% for a combined score of 40%, and the implied revenue multiple increases to 3.3x.

Winning Takes Both

The numbers above illustrate implied valuations based on a narrow set of assumptions. Dozens of other factors influence the merits of a given business model. Your mileage may vary. But what we have learned over the years is the combination of durable margins and proven growth is one of the best barometers of success for an RIA’s business model.

In the early days of racing, most sports cars focused on either straight-line speed (Ferrari, Corvette) or maneuverability (Porsche, Lotus). Times have changed. Today, winning takes both. In the RIA space, strong growth and big margins are hallmarks of a winning business.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights