Do Oil And Water Mix? The Biggest Energy IPO Of 2019 Might Answer That Question

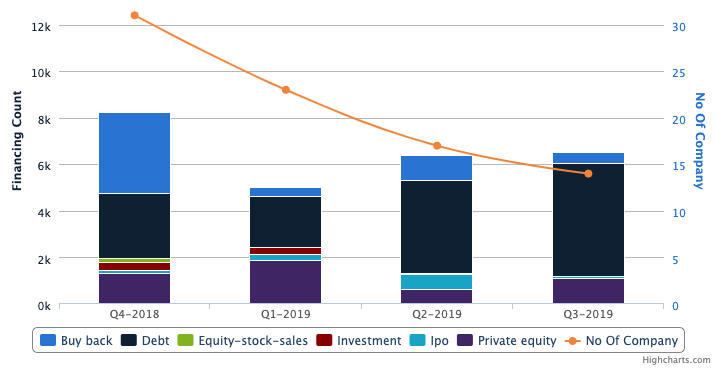

The capital markets in the upstream sector are leaving companies and investors in the lurch right now. Compared to 2018, equity and debt issuances have declined markedly and IPO’s in the sector have been relatively quiet apart from Brigham Minerals’ successful offering.

Saltwater disposal and integrated water logistics companies have attracted a higher proportion of the sparsely available capital flowing into the sector, highlighted by the largest energy IPO of this year: Rattler Midstream LP. The continuing austerity trend toward cash flow sustainability for shale oil companies has provided limited attractive options for investors. In the meantime, drilling activity (particularly in West Texas) continues to grow, and therefore efficiency and scale grow ever more important across the board for upstream companies to remain competitive. One of the challenges producers face is handling the enormous amounts of water that have become part and parcel to the Delaware and Midland Basins. This is where saltwater disposal enters the picture.

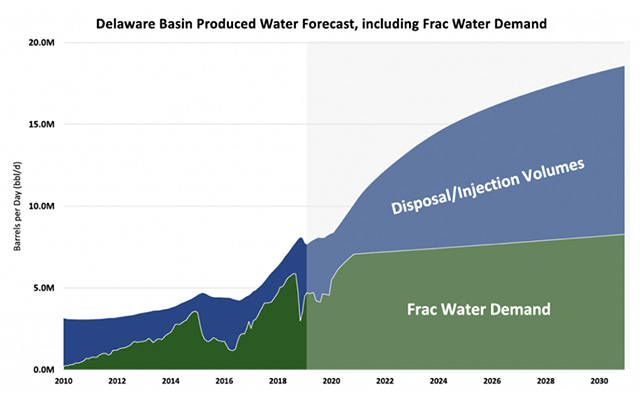

A horizontal well in the Delaware Basin can average four barrels (sometimes even up to 10 barrels) of water for every barrel of oil produced. Once produced, all that water must go somewhere and that somewhere is a saltwater disposal well. This is no new phenomenon as produced water has been an element of production for over 70 years. What is different in the Permian Basin is the higher ratio of water to oil (often called a “water cut”) that’s produced due to the native geology and today’s production techniques. Today’s U.S. oilfield water production is already around a colossal 50 million barrels a day. This contrasts with the U.S. producing only 15 million barrels of petroleum liquids every day. Most of that water is produced in the Permian Basin and there’s only going to be more of it. Much more. That’s to say nothing of the amount of water needed to fracture the rock during the production process. In a recent Raymond James research report, the authors noted that each well completion uses thirty Olympic swimming pools worth of water.

This water needs to be transported, sometimes long distances, and logistically managed. This function is trending towards consolidation whereby a single entity combines these assets and services. Until the past couple of years there was very little aquatic pipeline infrastructure. Most was handled by trucking, but that is changing as increasing volumes are raising scrutiny on the inefficiency of trucking. Growing demand in West Texas has opened up an estimated $12 billion-dollar market potential in the Permian Basin alone, according to Raymond James.

Fees for transporting and disposing produced water typically range from $0.50 to $2.50 per barrel. In addition, there is skimmed oil that can be gathered as well. However, where long distances stand between a production site and disposal infrastructure it can creep up to $4.00 to $6.00 per barrel. In today’s commodity price environment and focus on break-even prices, every dollar per barrel counts. Thus, there is a real incentive to improve infrastructure and push service costs lower.

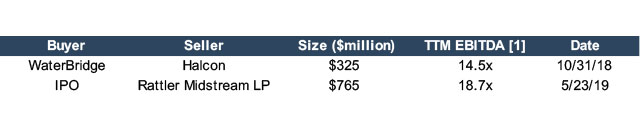

The investment merits of this water infrastructure include the opportunity for more steady business; with long term contracts tied to dedicated acreage, and stable cash flows that can fetch higher valuations than even some of the shale producers themselves in the region. It has been noted that some producers cannot begin drilling in certain areas until the water infrastructure is in place. In addition, there are consolidation opportunities for more fragmented business models between saltwater disposal facilities, equipment rental companies and pipeline companies. More integrated firms that combine these services will function more like traditional midstream operators. The trend has already begun and is being seen in valuations already. Rattler’s $765 million IPO opened at over 18 times EBITDA and recent water driven asset sales have traded between five- and ten-times EBITDA. For example, private equity backed WaterBridge purchased $325 million of Delaware Basin assets (assuming earnouts are paid) from Halcon Resources at an implied 14.5x trailing EBITDA multiple. Firms like NGL Energy Partners and EVX Midstream are also active in the space. Additionally, the opportunity for yield (which energy investors are craving) in the future can be more demonstrable than many upstream opportunities in the oil patch.

Amid this activity, landowners are also finding another source of income from royalties stemming from new pipeline and below ground storage rights as well, leading to more local income for ranchers and residents as well as another potential asset base for mineral aggregators and related investors to pursue. Oil and water do appear to mix, and energy bankers will be glad to know they do because it is filling gaps for an otherwise tight capital market space.

Originally appeared on Forbes.com.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights