U.S. Energy and Private Equity

Show Me the Money

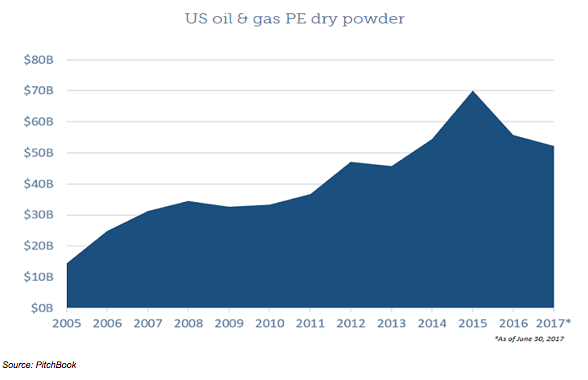

Private equity companies in the energy sector are positioned for an interesting opportunity. These companies have seen a surge of fundraising in recent years, leaving managers with large cash reserves or “dry powder” to be appropriately deployed. Despite the large amount of cash available, these firms are having trouble finding places to invest resulting in a decline in PE activity in 2016-2018 with deal counts dropping for the second year in a row by 8%. However, investments could see a marked increase in energy in the last quarter of 2018 and into 2019 as there is a climate of high demand for return on investment and low supply of cash needed for capital expenditures in upstream oil companies.

Oil and gas prices in 2018 have been steadily increasing in the midst of strong demand and constrained supply, and the U.S. energy sector is at the center of this focus. Forecasts from the International Energy Agency (IEA) show that the U.S. is expected to supply almost 60% of the demand growth over the next 5 years as conventional discoveries outside of the U.S. have hit historic lows since the early 1950s.

Supply-Side Problems

U.S. companies seem adequately poised to capture business in the swelling energy market, but the mechanics needed to supply this demand growth are turning out to be somewhat problematic. Upstream management teams that survived the oil crash in 2014 have had to cut costs aggressively in order to stay afloat, with capex spending plummeting nearly 45% between 2014-2016. These cost cuts, while necessary a few years ago, have largely continued into 2018 and conflict with the strong increase in spending that is needed to improve daily output to reach current demand. Morgan Stanley believes this output has to increase by 5.7 million barrels per day by 2020 in order to keep up. This level of increased production has only happened once since 1984.

Another issue facing supply is the lack of new oil discoveries. According to a study performed by Rystad Energy, discovered resources have fallen to an all-time low of around 7 billion barrels of oil equivalent in 2017. At current consumption rates, that is a replacement rate of around 11%, down from 50% in 2012. Not only are there fewer discoveries being made, but the sites found contain much less oil than prior discoveries.

International Alleviation

Russia and members of OPEC met in June and agreed to boost their collective output of oil production, amid U.S. sanctions on Iran, in order to help with the global shortfall and meet increased demand. Although there was no clear guidance on the increased output, the group has been tentatively aiming for an additional million barrels per day to overall production. World total oil supply has risen by approximately 680,000 barrels per day in July, but this was largely contributed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a group of non-OPEC members that includes the U.S.

In fact, from recent figures, Russia’s increased output amounted to only 20,000 barrels a day, and Saudi crude output actually decreased by 200,000 barrels a day. The decline in the oil production in Iran and Saudi Arabia and lackluster production boosts from Russia are proving that any alleviation in oil prices will come later as prices continue to rise. While the IEA agrees that the Saudis can supply over 12 million barrels a day, there is little incentive to do so as fiscal breakeven figures for Saudi oil production provided by the IMF show nearly $88 per barrel. Why turn on the spigots if there is no profit to be made?

Shortfalls in Capex

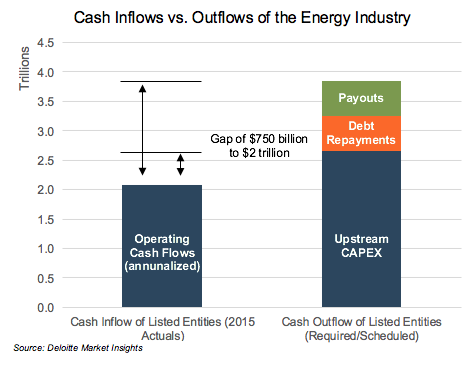

The U.S. has been ramping up production to make up for the underwhelming boost in international output. For the U.S. to continue to operate at the required level to reach demand, large investments in capex are necessary. From a Deloitte study in 2016, the industry needs a minimum investment of about $3 trillion from 2016-2020 to ensure its long-term sustainability even in the case of non-linear demand. When paired against the operating cash inflows and the required cash outflows of listed entities, there is a gap of roughly $750 billion to $2 trillion to cover payouts, debt repayments, and upstream capex.

Even if companies have enough operating cash flow to fund capex on the lower levels, capex may not have the first call on available cash. Other balance sheet focuses and maintenance of reduced payouts may command higher priority for that cash.

So where does the money come from to close the capex gap and supply the growing demand? This is where private capital and U.S. shale come into play.

Private Equity Factors

As the price of oil steadily increases, private equity backers for these upstream companies should see a similar uptick in new fundraising. Historically, rising prices equates to higher investment returns. The scenarios outlined above create an opportunity for energy investors that is not likely to be seen again for many years. Not only is the demand outlook in the investors’ favor, but the return per dollar invested is attractive as well due to innovations in efficiency from U.S. companies, as mentioned in a prior blog post, in areas like the Bakken. Well completion times have fallen by roughly half since 2013, which allowed for U.S. upstream companies to profit on $30 per barrel.

The disconnect between rising prices and the relative performance of publicly traded energy companies creates an opportunity for private ventures to collect properties and assets and start drilling. Global private equity raised a record of $453 billion from investors in 2017 leaving it with more than $1 trillion to put into companies and new business ventures. Subsequently, this has resulted in the record amounts of dry powder in $1 billion+ funds. Coming into 2018, U.S. oil and gas PE funds alone were holding around $52 billion in dry powder, which can be seen in the PitchBook figure below. EnCap Investments was the largest player holding approximately $6.75 billion to be deployed in its Energy Capital Fund XI. Other industry giants such as Riverstone Holdings and Blackstone are holding around $3 billion and $2.7 billion, respectively.

With such a large influx of new capital waiting to be deployed, the energy sector offers attractive opportunities to capitalize on the high level of demand coupled with rising prices and need for capital.

Challenges

The challenges typically facing energy-focused private equity companies are that they tend to be risk-averse. New discoveries and new drilling are capital intensive in both cash and time. PE firms tend to gravitate toward established shale plays and, as a consequence, pay a hefty premium for a “sure bet.” As a result, one could argue the better use of capital would be making a long only bet on NYMEX and avoid the liabilities of owning an operating company.

Additionally, the time horizons of these PE sponsors are often mismatched with the energy sector cycles. Cycles and manipulations by OPEC can occur over many years or even decades, while the typical time horizon for a PE sponsor is generally around 7 years.

Conclusion

Private equity firms are positioned to capture a rare investment opportunity in the U.S. energy sector.

History has shown that there is a connection between higher oil prices and higher investment returns. In this relatively high price environment, private equity backers can supply the key ingredient of large capital injections to close the much-needed capex gap in U.S. upstream oil companies and enjoy the subsequent investment returns.

We have assisted many clients with various valuation needs in the upstream oil and gas in North America and around the world. Contact a Mercer Capital professional to discuss your needs in confidence and learn more about how we can help you succeed.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights