Is Growth Optional for Your Family Business?

This post is part of our “Talking to the Numbers” series for family business leaders. In this series of posts, our goal is to help family business directors ask the right questions when reviewing financial statements. Asking better questions will lead to better financial and business decisions.

The income statement is a natural place to begin analyzing a company’s financial results, and revenue is the natural starting point for that analysis. We recently heard someone remark that everything good in business starts with revenue, and our experience working with family businesses of all stripes confirms that sentiment. While the absolute amount of revenue can be instructive (i.e., are we looking at a $10 million business or a $100 million business?), it is the trend in revenue that is most revealing. Is the business growing, treading water, or shrinking?

Analyzing the Public Company Data

To gain a little more perspective on revenue growth for our benchmark universe of public companies, we pulled revenue figures for the five years ending with 2017. Comparing the 2017 revenue figures to 2013 revenues, we calculated the compound annual growth rate (or CAGR) for each company. For multi-year periods, the compound annual growth rate smooths out year-to-year variations and represents the overall annualized growth rate for the period.

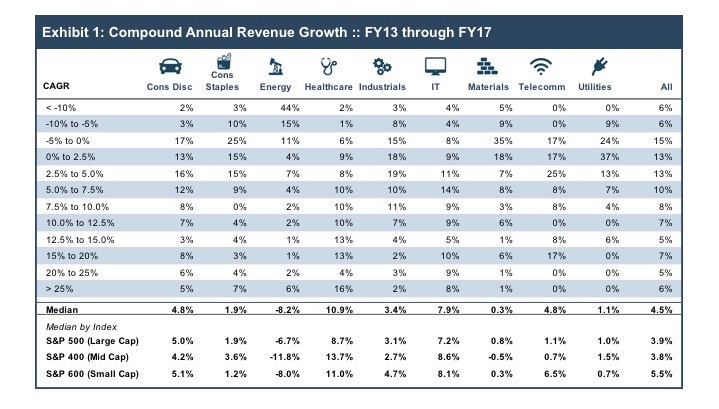

Exhibit 1 summarizes the compound annual growth rates for the benchmark universe. (For some background on this data set, see the first post in this series.)

The top panel of Exhibit 1 indicates how revenue growth is distributed for each industry. For example, 16% of the consumer discretionary companies in our sample (the leftmost column), reported CAGRs between 2.5% and 5.0%, while 5% of such companies reported a CAGR in excess of 25%. In other words, each vertical column sums to 100%. The bottom panel indicates the median observed CAGR for each industry by index (which is a proxy for company size).

Takeaways for Your Family Business

Pondering over this data for a while, we offer a couple of observations for family business directors.

1. Industry Sets the Stage for Growth, but Does not Define It.

The industry a business operates in is a powerful force in setting expectations for revenue growth. The differences in median CAGR across industries in Exhibit 1 are not trivial. At the extreme ends of the spectrum, energy company revenues over the period were hamstrung by a decline in oil prices (median CAGR of negative 8.2%), while healthcare companies were generally boosted by that sector’s growing share of the overall economy (10.9% annualized growth).

However, the overall distribution of growth rates by industry is actually quite wide. Take for example consumer staples (the second column from the left). The median annualized revenue growth of 1.9% reflects a mature industry that – as a whole – is largely dependent on inflationary price increases for revenue growth. And yet nearly a quarter of the companies in that industry generated CAGRs in excess of 10%. What this suggests is that, even in mature, slow-growth industries, successful management teams can identify and execute on paths to revenue growth.

Directors should be thinking about how industry dynamics are influencing revenue growth.

In the context of a family business, directors should be thinking about how industry dynamics are influencing revenue growth. For example, a compound annual growth rate of 3.5% over the period examined would be consistent with maintaining market share for an industrial company, gaining market share for a consumer staples firm, and losing market share for a healthcare business. In other words, the same signal can carry different meanings for companies in different industries. As a family business director, you should ask yourself questions like the following:

- Does our family business have a strategy that acknowledges the reality of the industry but identifies opportunities to increase market share profitably?

- What sorts of strategies are most likely to increase market share for our business within the industry? Differentiating on quality and service? Or becoming a value leader?

- Where is the low-hanging fruit for revenue growth: price increases, geographic expansion, adding an adjacent product line, marketing to new customers, or something else?

2. Revenue Growth Can Be Organic or Acquired

For the industry as a whole, revenue growth is all organic (i.e., selling more widgets at potentially higher prices). However, for individual companies within an industry, revenue growth can be augmented by acquisitions. Organic growth requires a sustainable competitive advantage. Acquisition growth requires discipline to avoid overpayment.

Real, long-term organic growth is hard. Absent one or more strategic “moats” around the company’s market niche, profits draw competition. What is unique about your family business that can contribute to sustained organic revenue growth?

Supplementing organic growth with acquired growth brings its own set of challenges. Like nearly everything else in business, investing for growth is subject to the law of diminishing marginal returns: the more growth projects a company undertakes, the less effective the projects are likely to become. As a result, pursuing revenue growth without regard for the marginal efficiency of investment can actually prove detrimental to family shareholders. In other words, revenue growth must always be evaluated relative to the cost to achieve it.

What is unique about your family business that can contribute to sustained organic revenue growth?

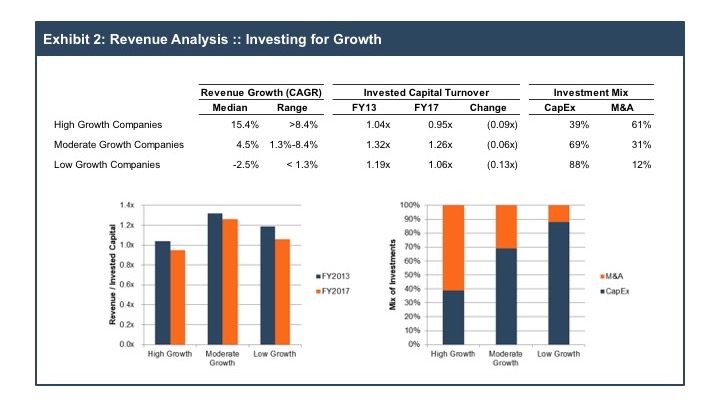

One simple measure of investment efficiency is the ratio of revenue to invested capital (the sum of debt and equity financing). This ratio measures the revenue generated per dollar of capital used by management. If the ratio decreases over time, it suggests that the incremental investments made to achieve revenue growth are becoming less effective.

The data summarized in Exhibit 2 suggests that – in aggregate – the public companies in our data set demonstrated imperfect discipline with regard to pursuing revenue growth. We sorted the companies in our sample by revenue growth, creating three subgroups of equal size. While the overall revenue turnover slipped a bit for all companies over the period analyzed, the high growth companies fared no worse than the low growth companies: in other words, the high growth companies were not chasing growth recklessly at the expense of shareholder returns.

Corporate investment may take the form of either capital expenditures or merger & acquisition activity. Exhibit 2 also summarizes the relative mix of investment for the subgroups of companies. The data suggests that the high growth companies rely more heavily on M&A, while the low growth companies tend to focus more on capital expenditures. If we assume that capital expenditures are a (very imperfect) proxy for organic growth, this data confirms that the fastest growing firms are augmenting organic growth opportunities with strategic acquisitions.

For family business directors thinking about revenue growth, this leads to some important questions.

- Does our family business have a culture that can accommodate growth through acquisition, or is organic growth the primary path forward?

- Are there logical acquisition targets that could boost revenue growth (at a reasonable price)?

- Does our company have the financial capacity to make an acquisition?

- Does our business have a qualified team of advisors to help execute on acquisition opportunities?

In sum, revenue growth analysis for a family business should focus on industry dynamics and the opportunities for organic vs. acquired growth.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director