It’s Getting Real(ized)

As has been recently discussed by many, the significant rise in yields across the Treasury curve, with the most notable increase occurring at the short-end of the curve, has resulted in large unrealized losses in bank securities portfolios. From March 2022 through July 2023, the Federal Reserve increased the target Federal Funds rate eleven times for a collective increase of 525 basis points. Since the last 25 basis point increase in July 2023, the Federal Reserve has opted to hold the target Fed Funds rate steady.

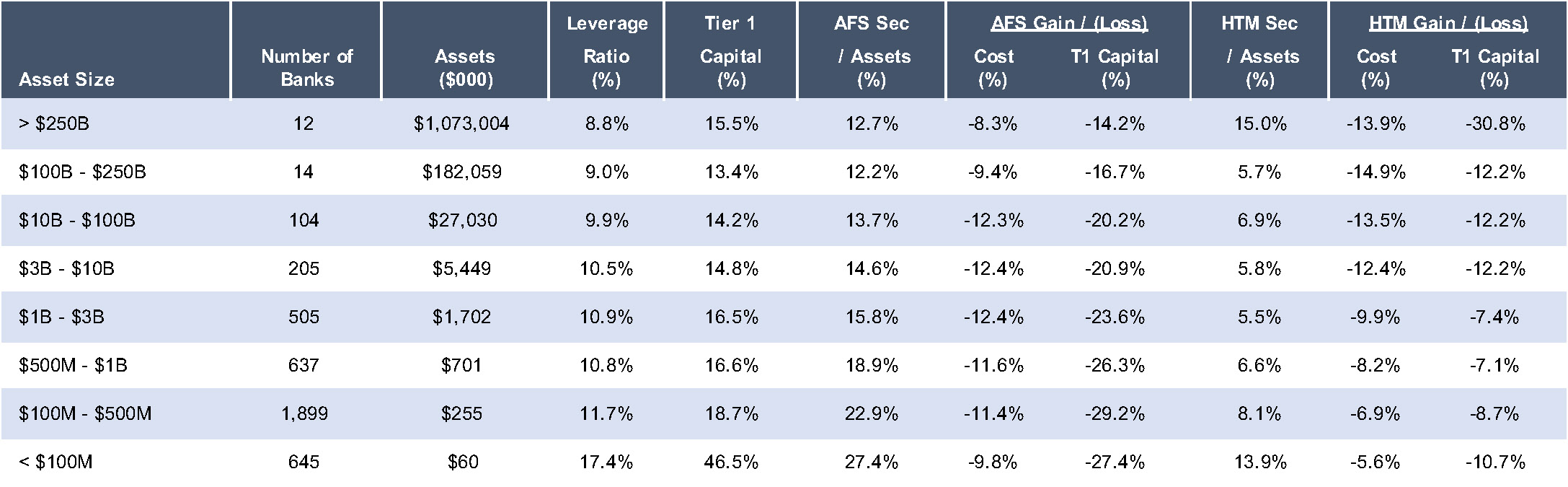

To start, we provide an update of a data table we’ve included in prior versions of Bank Watch regarding unrealized losses in bank bond portfolios.

Unrealized losses in available-for-sale (“AFS”) designated portfolios range from an average of 8.3% for banks with assets greater than $250 billion to 12.4% for banks with $1 billion to $3 billion of assets and banks with $3 billion to $10 billion of assets. As a percentage of Tier one capital, the range was from 14.2% for banks with assets greater than $250 billion to 29.2% for banks with $100 million to $500 million of assets.

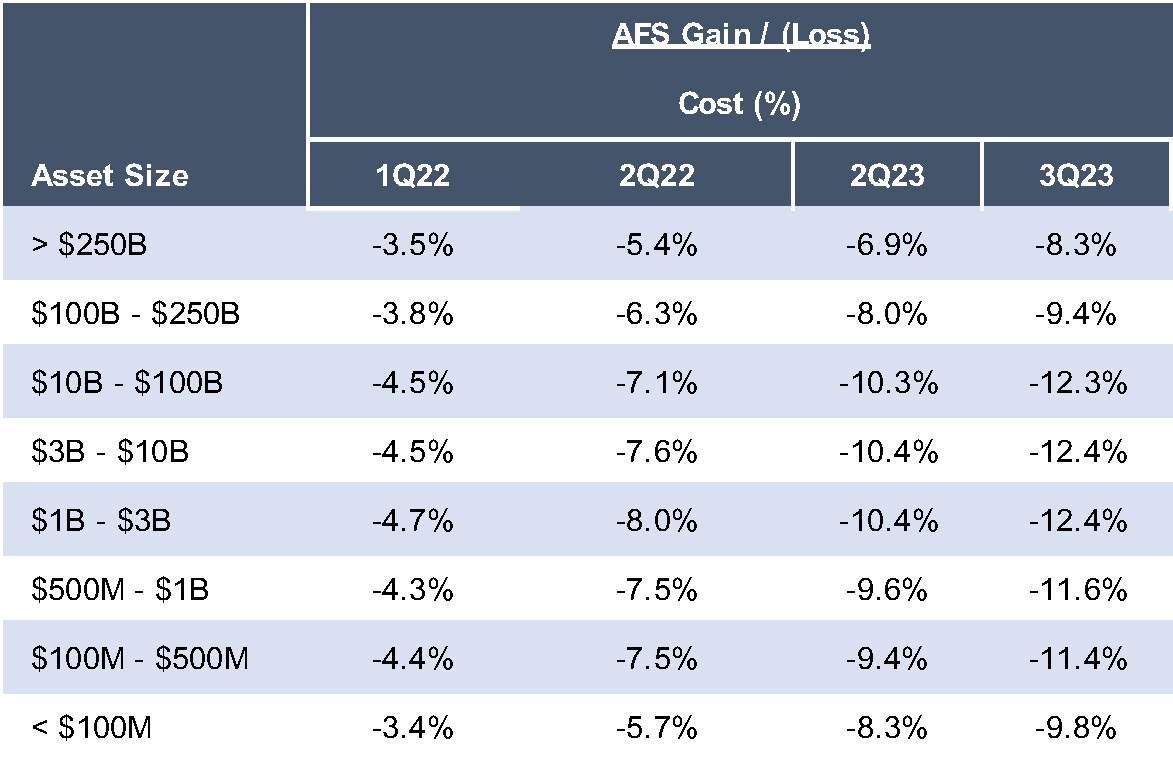

For additional perspective on the trend in bond portfolio losses, the following table depicts unrealized losses in AFS portfolios for 1Q22, 2Q22, 2Q23, and 3Q23. As shown below, the magnitude of losses has steadily increased for all banks since the Fed began raising rates in early 2022.

In our September publication of Bank Watch, my colleague Andy Gibbs covered some implications of a higher-for-longer rate environment. In discussing what banks should do with internally generated capital if the return on capital from more aggressive loan growth strategies is diminished, Gibbs wrote:

A more controversial strategy would entail using some excess capital to effectuate a partial restructuring of the bond portfolio. Rather than tying up capital with loans earning a relatively low spread over marginal funding costs, a bank could exit some low yielding investments at a loss that could be replaced with investments at current market rates (or used to pay down costly borrowings).

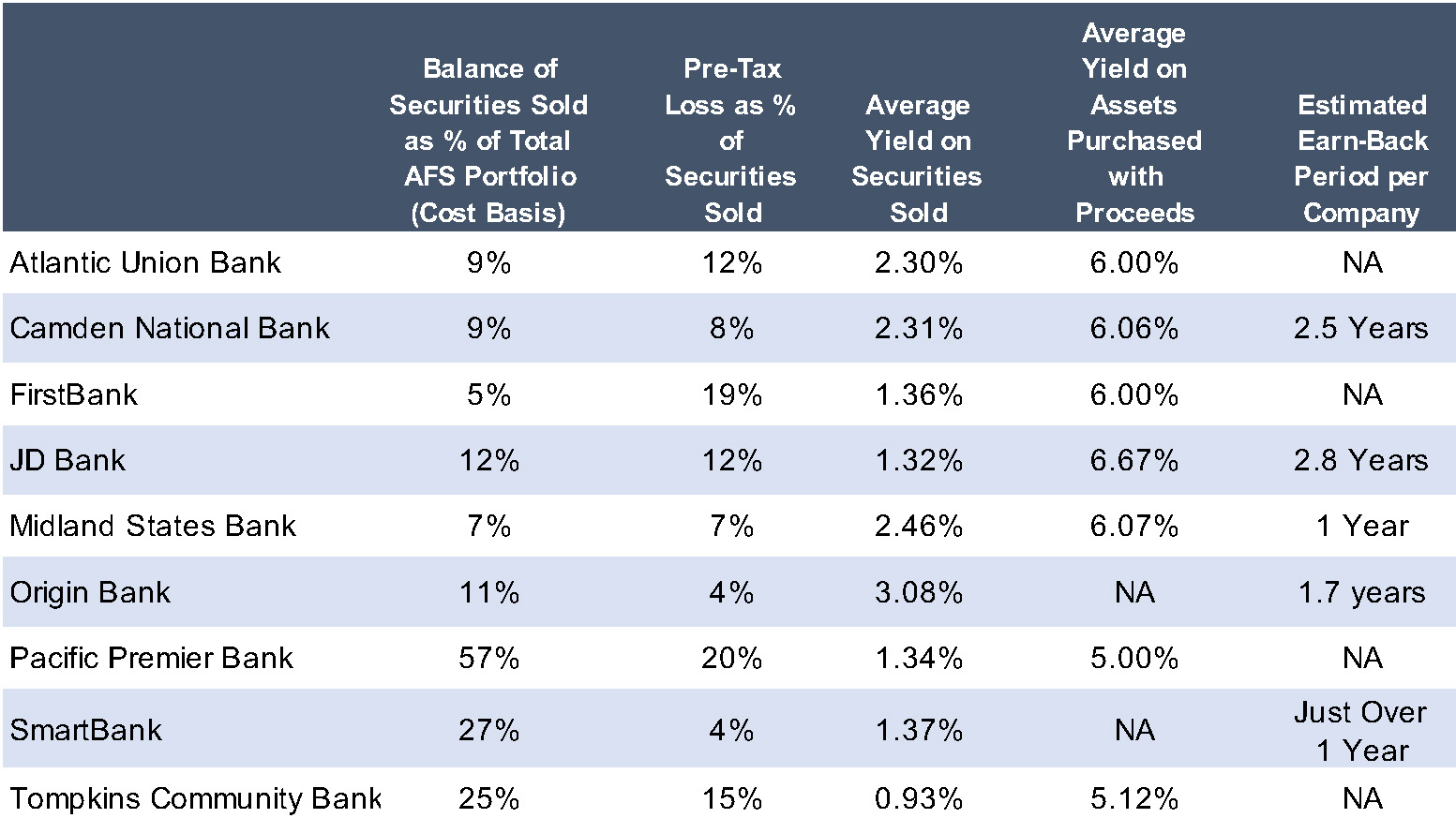

In the third and fourth quarters of 2023, securities portfolio restructuring is a strategy that appears to be gaining momentum. Mercer Capital reviewed regulatory, SEC, and various public filings for some of the banks that have announced such actions. In the following table, we’ve summarized some data points of interest for our sample of banks that elected to reposition the securities portfolio in the third or fourth quarter.

Unless rates decrease significantly, losses on securities will be realized in either of two ways: (i) immediately, through losses on sale or (ii) over time, through lower earnings. As illustrated in the table above, one of the potential pros of selling securities immediately is net interest margin enhancement, as proceeds from the sale of underwater securities can be reinvested in higher yielding assets. For the banks that reported the average yield on securities sold and the average yield on assets purchased with the proceeds from the sale, the pick-up in yield ranged from approximately 360 bps to 535 bps.

Another potential pro is the ability to repay high-rate borrowings with the proceeds, which is what OBK chose to do. After selling securities with an average yield of 3.08%, the proceeds were used to pay down outstanding FHLB advances with an interest rate of 5.62%. OBK noted an expected 11 bps pickup in its NIM from the trade. Other potential pros of selling underwater securities include reduced interest rate risk and closure of decisions made in a low-rate environment.

Banks undertaking bond restructurings expect accretion to shareholder value, as higher net interest income leads to higher earnings in 2024 and beyond which supports a higher stock price. In a perfectly efficient market, a bond restructuring should have no impact on a bank’s share price, as the market has already discounted the impact of low yielding bonds purchased in a different interest rate environment. But the market is not perfectly efficient.

In our sample, JD Bancshares, Inc., Tompkins Financial Corporation, and Pacific Premier Bancorp, Inc. are the only companies that announced the securities portfolio repositioning separately from earnings. Given limited trading volume for JDVB, we focused on the change in stock price for TMP and PPBI post announcement of the bond portfolio restructuring. From the day prior to the announcement to three days after, TMP’s stock price increased 2.0% and PPBI’s stock price increased 3.0%. For comparison, the S&P U.S. BMI Banks Index declined by 3.9% and 3.2% over the same time periods.

While there are certain benefits to a securities portfolio restructuring, there are also cons to consider. For one, banks must have adequate capital to be able to absorb the hit when previously unrealized losses are realized, and the impact to capital may not be tolerable for some banks. Furthermore, lower capital affects the potential size of the balance sheet, due to minimum capital ratios, and therefore affects earning potential. For example, a reduction in capital from a bond portfolio restructuring could constrain organic growth or M&A opportunities. Finally, beyond the traditional capital ratios, banks should be aware of the impact of a bond restructuring on the CRE loan/capital ratio, which has received greater regulatory focus.

Other potential disadvantages of selling underwater securities and repositioning the portfolio include investor/customer reaction and the uncertainty regarding future rates. Rates could decrease before the securities loss is earned back through higher net interest income. As shown in the table on page 2, the earn-back period in our sample ranged from 1 to 2.8 years, for the companies for which this metric was reported. Some compensation arrangements, if linked to reported net income, may be affected by a bond restructuring.

Finally, banks should monitor accounting developments. An argument exists that if bond sales occur as part of an integrated series of transactions this could result in all, or a significant share of, the available-for-sale securities portfolio being marked to market through earnings rather than shareholders’ equity.

Earn-Back Math

The earn-back period calculation appears simple—divide the equity impact of the bond portfolio restructuring by the after-tax earnings enhancement—but is subject to considerable discretion. Digging into the math of a bond portfolio restructuring reveals the following:

The pick-up in yield is not as simple as comparing the yield on the bond sold to the yield on the replacement bond. Assume a bank has a bond with a par value of $1,000 with a 2.00% rate, which it sells for $750. The bank receives $750 of cash that it can use to buy a new bond yielding 5%. The pick-up in income is not 3% (the difference between the 5% yield on the new bond and 2% on the old bond). Instead, the bank gives up $20 of income ($1,000 x 2%) and will earn $37.50 going forward ($750 x 5%). That is, the pick-up in income is only $17.50, which is much less than suggested by the spread between the yields on the new and old bonds.

The earn-back period is affected by the selection of bonds sold. Holding other factors constant, if a bank desires a short earn-back period, it should sell bonds with shorter durations (and lower losses on sale). Selling long-term bonds with higher losses will produce a longer earn-back period.

As an example, assume a bank is evaluating two bond portfolio restructurings. The first includes bonds with a 2% yield and a two year duration, while the second liquidates bonds with a 2% yield and a 20-year duration. The denominator in the earn-back calculation (the after-tax earnings enhancement) is likely to be similar in the near-term regardless of which scenario occurs. However, the first scenario would entail a lower loss on sale (which affects the numerator in the earn-back calculation), thereby producing a shorter earn-back period.

If your bank would like a second opinion on the merits of a potential bond restructuring, please contact a member of Mercer Capital’s Financial Institutions Group.