Supreme Court Upholds Connelly

Life Insurance Proceeds and Redemption Obligations in Buy-Sell Agreements

The United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh Circuit, rendered a decision in the matter of Estate of Blount v Commissioner of Internal Revenue in October 2005.1 The primary takeaway from that decision was that life insurance used as a funding vehicle to pay a company’s liability to repurchase shares upon the death of a shareholder does not add to the value of the company for federal gift and estate tax purposes.

The United States Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit, rendered a decision in the matter of Thomas Connelly v. United States in June 2023.2 The primary takeaway from that decision is that life insurance received at the death of a shareholder is a corporate asset that adds to the value of the company for federal gift and estate tax purposes.

Given this apparent split in the decisions of the Eighth and Eleventh circuits, the Eighth circuit’s case was offered to the Supreme Court of the United States on writ of certiorari. The Supreme Court of the United States (“SCOTUS”) rendered its decision in the matter of Connelly, as Executor of the Estate of Connelly v. United States (602 U. S. _____(2024), decision rendered June 6, 2024). The unanimous decision of the Supreme Court was rendered by Justice Thomas, who wrote in summary:

Michael and Thomas Connelly owned a building supply corporation. The brothers entered into an agreement to ensure that the company would stay in the family if either brother died. Under that agreement, the corporation could be required to redeem (i.e., purchase) the deceased brother’s shares. To fund the possible share redemption, the corporation obtained life insurance on each brother. After Michael died, a narrow dispute arose over how to value his shares for calculating the estate tax. The central question is whether the corporation’s obligation to redeem Michael’s shares was a liability that decreased the value of those shares. We conclude that it was not and therefore affirm.

I am not a lawyer and am careful when analyzing cases. However, it appears that SCOTUS wrote its decision in a very narrow fashion. It did not, for example, appear to reject the Eleventh Circuit’s decision in Blount, but affirmed the Eighth Circuit’s decision in Connelly.

At the very least, in light of the Supreme Court’s ruling, every buy-sell agreement funded by life insurance should be reviewed by competent legal and tax counsel to ensure that the agreements operate as planned when triggered.

Basic Facts of Connelly

The basic facts can be summarized as follows:

- Michael and Thomas Connelly, brothers, were the owners of Crown C Supply (“Crown” or “the Company”), a company located in St. Louis, Missouri.

- Michael owned 385.9 shares representing 77.18% of the shares outstanding.

- Thomas owned 114.1 shares representing 22.82% of the shares outstanding.

- On August 29, 2001, Michael and Thomas entered into a stock purchase agreement to ensure that Crown would stay in the family if either brother died. The agreed upon value (certificate of value) at that time was $10,000 per share, or $5 million. Under the agreement, the surviving brother had an option to purchase the deceased brother’s shares. If a brother declined to purchase, Crown would be required to purchase the deceased brother’s shares.

- The agreement called for an appraisal process to determine the fair market value of a deceased brother’s shares. Crown was to select an appraiser and the estate of a deceased brother was to select another. Both were to provide fair market value opinions. If the two appraisal conclusions were more than 10% apart, the appraisers would select a third appraiser, who would also provide an opinion of fair market value.

- Crown obtained $3.5 million of life insurance on each brother’s life, which at some point was reduced to $3 million.

- Michael died on October 1, 2013.

- At the time of Michael’s death, there was no agreed upon certificate of value.

- Thomas opted not to purchase Michael’s shares, giving rise to Crown’s obligation to purchase Michael’s shares. The parties did not engage in any appraisal process, as called for in their agreement.

- Michael’s son and Thomas agreed in an “amicable and expeditious manner” that Michael’s shares were worth $3,000,000 (77.18% x $3,860.000 = $2,978,148) of an agreed upon value of $3,860,000). The purchase price resulted from what was described as an extensive analysis of Crown’s books and an extensive analysis of assets and liabilities of the company. Thomas, an experienced businessman extremely knowledgeable about Crown’s finances, was able to ensure an accurate appraisal of the shares.3

- Note the $3 million purchase price for Michael’s shares implied a value for 100% of Crown of $3.86 million ($3,000,000 / 77.18%). Recall that the certificate of value agreed upon in 2001 provided a value of $5,000,000 for Crown, or significantly higher than the agreed upon $3.86 million.

- Crown collected the life insurance proceeds and purchased Michael’s shares for ~$3,000,000, and Michael’s estate filed an estate tax return based on this value.

- The IRS audited the estate’s return and claimed a deficiency of $889,914, or 38.4% of the difference between $5,294,458 (life insurance is a corporate asset) and $2,978,148 (life insurance is a funding vehicle).

- Interestingly, there is no record of an appraisal conducted on behalf of the IRS. During the audit, the Company retained an accounting firm to provide an appraisal. The concluded fair market value, assuming that the obligation to repurchase Michael’s stock was a real liability, was $3.86 million.

- Reading between the lines in the earlier decisions, it seems that the IRS was more interested in challenging the use of life insurance proceeds as a funding vehicle rather than as a corporate asset. The case leaves a big question regarding the actual fair market value of Crown on the date of Michael’s death.

- Michael’s estate paid the deficiency, and Thomas, as executor, sued the United States for a refund.

- The District Court (Eighth Circuit) granted summary judgment to the Government, holding that to accurately value Michael’s shares, the $3 million in life insurance proceeds must be counted in Crown Supply’s valuation.4

- The Eighth Circuit affirmed.

- SCOTUS, in a unanimous decision written by Justice Thomas, affirmed the decision of the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Justice Thomas wrote:

The dispute in this case is narrow. All agree that, when calculating the federal estate tax, the value of a decedent’s shares in a closely held corporation must reflect the corporation’s fair market value. And, all agree that life insurance proceeds payable to a corporation are an asset that increases the corporation’s fair market value. The only question is whether Crown’s contractual obligation to redeem Michael’s shares at fair market value offsets the value of life insurance proceeds committed to funding that redemption.

Whether the SCOTUS decision in Connelly is the death knell of entity repurchase agreements is a question. However, the decision will raise questions and should require every company with company-owned life insurance on the lives of its owners to evaluate the effectiveness of their buy-sell agreements and related life insurance.

SCOTUS Example of a Redemption

Justice Thomas wrote:

An obligation to redeem shares at fair market value does not offset the value of life insurance proceeds set aside for the redemption because a redemption does not affect any shareholder’s economic interest. (at pp. 6-7) (emphasis added)

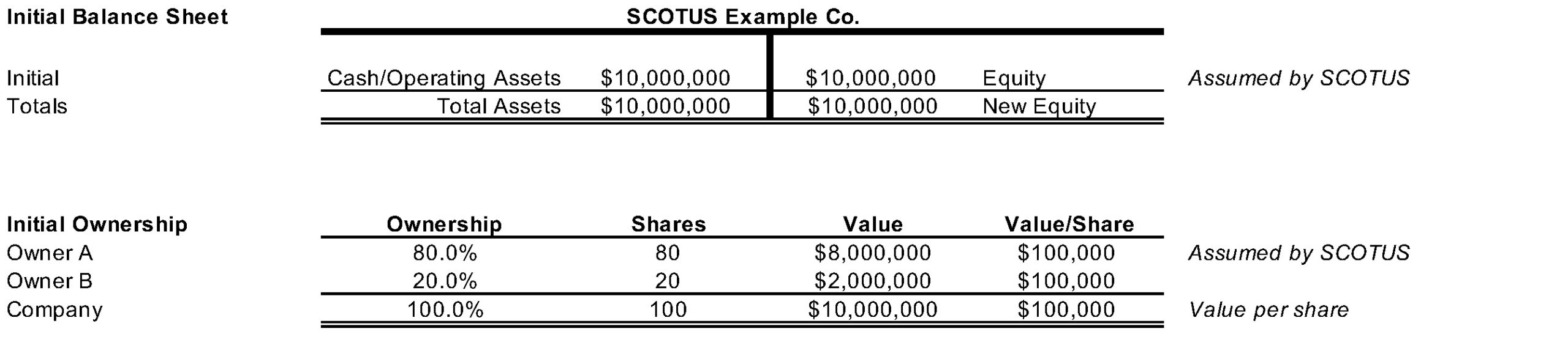

Following this statement, an example is provided in the text of the decision. We examine this example more visually in the analysis that follows. We call the hypothetical company in the decision “SCOTUS Example Co.” The initial balance sheet and ownership of SCOTUS Example Co. are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Click here to expand the image above

SCOTUS Example Co. has $10,000,000 in cash/operating assets. Owner A holds 80% of the stock which is worth $8,000,000. Owner B owns 20% of the stock, which is worth $2,000,000.

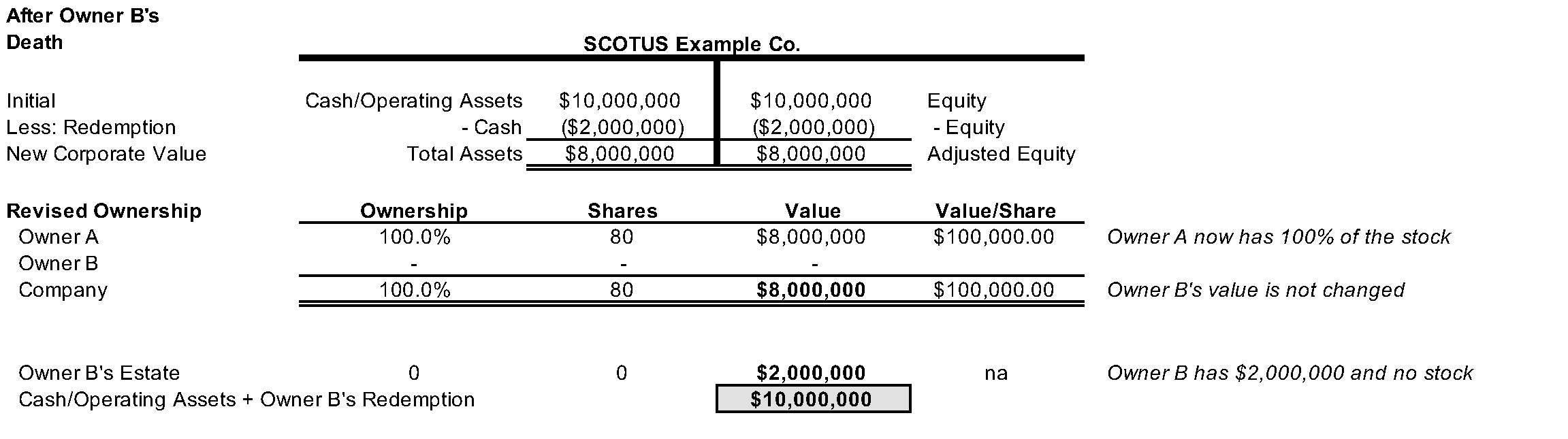

We assume that Owner B dies (and there is no life insurance) or that the Company simply redeems his 20% interest for $2,000,000. The Company retires Owner B’s shares to treasury, and now there are only 80 shares outstanding. The effect of this is to remove Owner B as a shareholder, lower the Company’s value by $2,000,000, and elevate Owner A to ownership of 100% of the shares now outstanding. The remaining $8,000,000 value of the Company plus the $2,000,000 in Owner B’s estate amount to $10,000,000, or exactly the value before the redemption of Owner B’s shares, as seen in Figure 2 .

Justice Thomas then concluded:

The value of the shareholders’ interests after the redemption – A’s 80 shares and B’s $2 million in cash – would be equal to the value of their respective interests in the corporation before the redemption. Thus, a corporation’s contractual obligation to redeem shares at fair market value does not reduce the value of those shares in and of itself.

It is an incorrect conclusion to suggest that the example redemption “does not affect any shareholder’s economic interest.” It is true that Owner B received the $2.0 million value of his shares in the example. Owner A’s interest, while still valued at $8.0 million as before the redemption, now represents a 100% interest in a smaller company. Owner A’s economic interest has, indeed, changed. Instead of owning the right to 80% of the economic benefits of the pre-redemption company, he now owns the rights to 100% of the economic benefits of a company that is different (smaller) than before.

Figure 2

Click here to expand the image above

There is a significant leap from the SCOTUS example to Justice Thomas’s conclusion. There is no life insurance in the example, yet it is the life insurance that is assumed to increase the value of Crown. We examine the case to understand the presumed reduction in value (or not) inferred in this conclusion.

Is Life Insurance a Corporate Asset or Is it a Funding Vehicle?

There are two opposing treatments of life insurance proceeds in valuations for purposes of buy-sell agreements. As I wrote in 2010 in a book about buy-sell agreements:5

Treatment 1 – Proceeds are a funding vehicle and not a corporate asset. One treatment would not consider the life insurance proceeds as a corporate asset for valuation purposes. This treatment would recognize that life insurance was purchased on the lives of shareholders for the specific purpose of funding a buy-sell agreement. Under this treatment, life insurance proceeds, if considered as an asset in valuation, would be offset by the company’s liability to fund the purchase of shares. Logically, under this treatment, the expense of life insurance premiums on a deceased shareholder would be added back to income as a nonrecurring expense.

Treatment 2 – Proceeds are a corporate asset. Another treatment would consider the life insurance proceeds as a corporate asset for valuation purposes. In the valuation, the proceeds would be treated as a nonoperating asset of the company. This asset, together with all other net assets of the business, would be available to fund the purchase of shares of a deceased shareholder. Again, under this treatment, the expense of life insurance premiums on a deceased shareholder would be added back to income as a nonrecurring expense.

The Internal Revenue Service in Connelly treated the life insurance proceeds as a corporate asset to be added to value in the determination of fair market value. This is Treatment 2 above. Michael’s estate argued that the life insurance proceeds should be treated as a funding vehicle to finance the redemption of a shareholder’s shares upon his death, which is Treatment 1 above (and, effectively, the conclusion in Blount).

SCOTUS Treatment of Life Insurance Proceeds

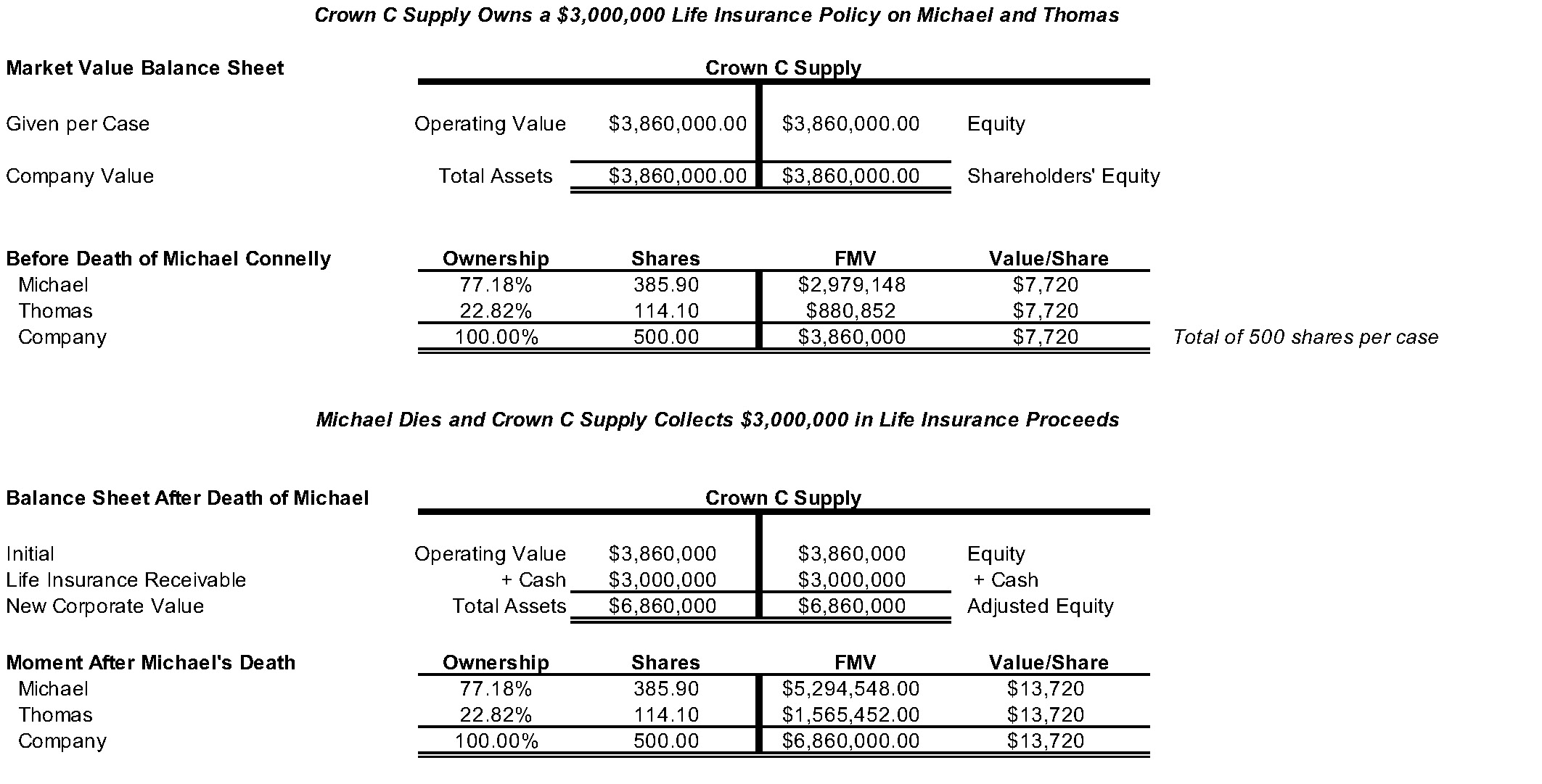

Using the same T-account analysis as with the discussion of SCOTUS Example Co. and a simple redemption, we now look at the effective treatment employed by the Internal Revenue Service and SCOTUS.

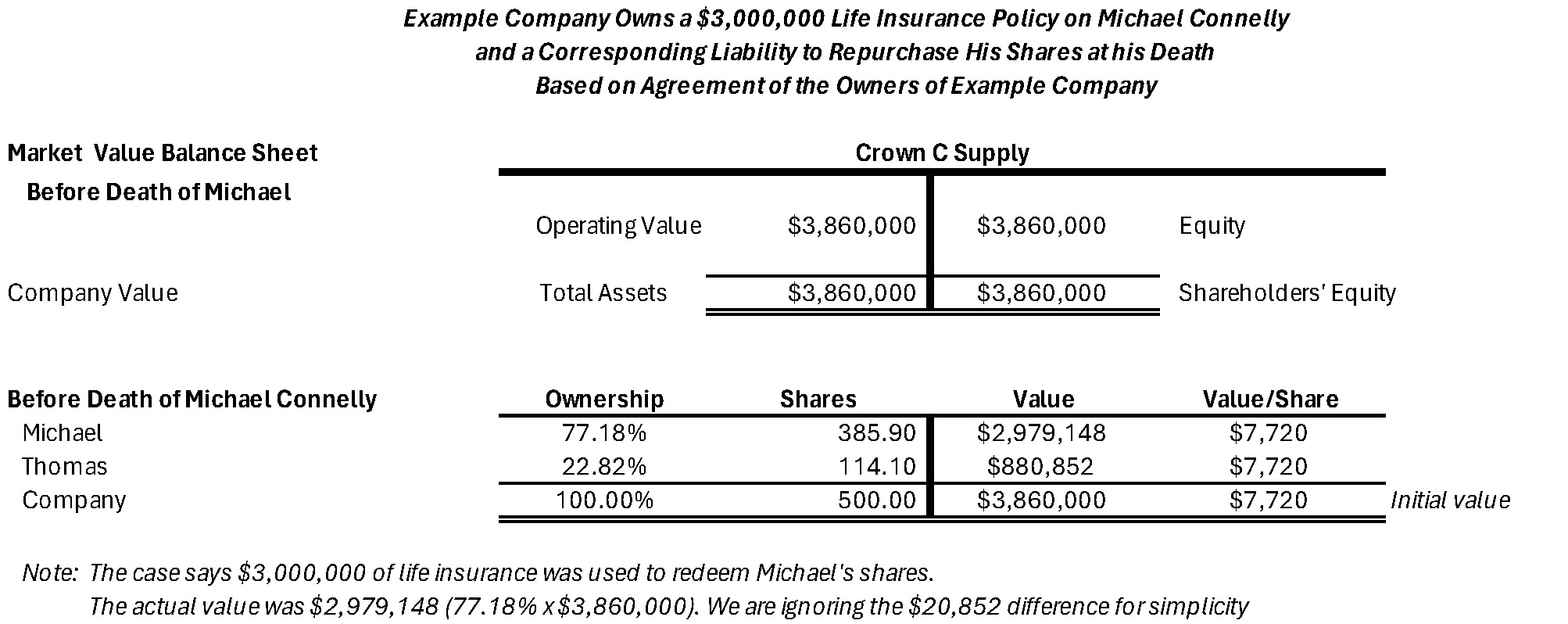

Accept as given that Crown had an operating value of $3.86 million (per the opinion), which is shown in the market value balance sheet at the top of Figure 3. Michael owned 77.18% with a value of $2,979,148 and Thomas owned 22.82% with a value of $880,852. These values represent their respective shares of the $3,860.000 of operating value.

Figure 3

Click here to expand the image above

Now we examine the balance sheet after Michael’s death. The life insurance of $3,000,000 (receivable) is added to the balance sheet as an asset and as equity, raising the total value of the Company to $6.86 million. Michael’s shares were worth $5,294,548 and Thomas’s shares were worth $1,565,452. In both cases, their values per share had risen from $7,720 per share to $13,720 per share, or $6,000 per share ($3,000,000 of life insurance divided by 500 shares outstanding).

In the “Syllabus” released with SCOTUS’s Connelly decision, we see the root of the confusion.6

Thomas’s argument that the redemption obligation was a liability also cannot be reconciled with the basic mechanics of a stock redemption. He argues that Crown was worth $3.86 million before the redemption, and thus, that Michael’s shares were worth approximately $3 million ($3.86 million x 0.7718). But he also argues that Crown was worth $3.86 million after Michael’s shares were redeemed. See Reply Brief 6. Both cannot be right. A corporation that pays out $3 million to redeem shares should be worth less than before the redemption.

Finally, Thomas asserts that affirming the decision below will make succession planning more difficult for closely held corporations. But the result here is simply a consequence of how the Connelly brothers chose to structure their agreement. (Pp. 5-9)

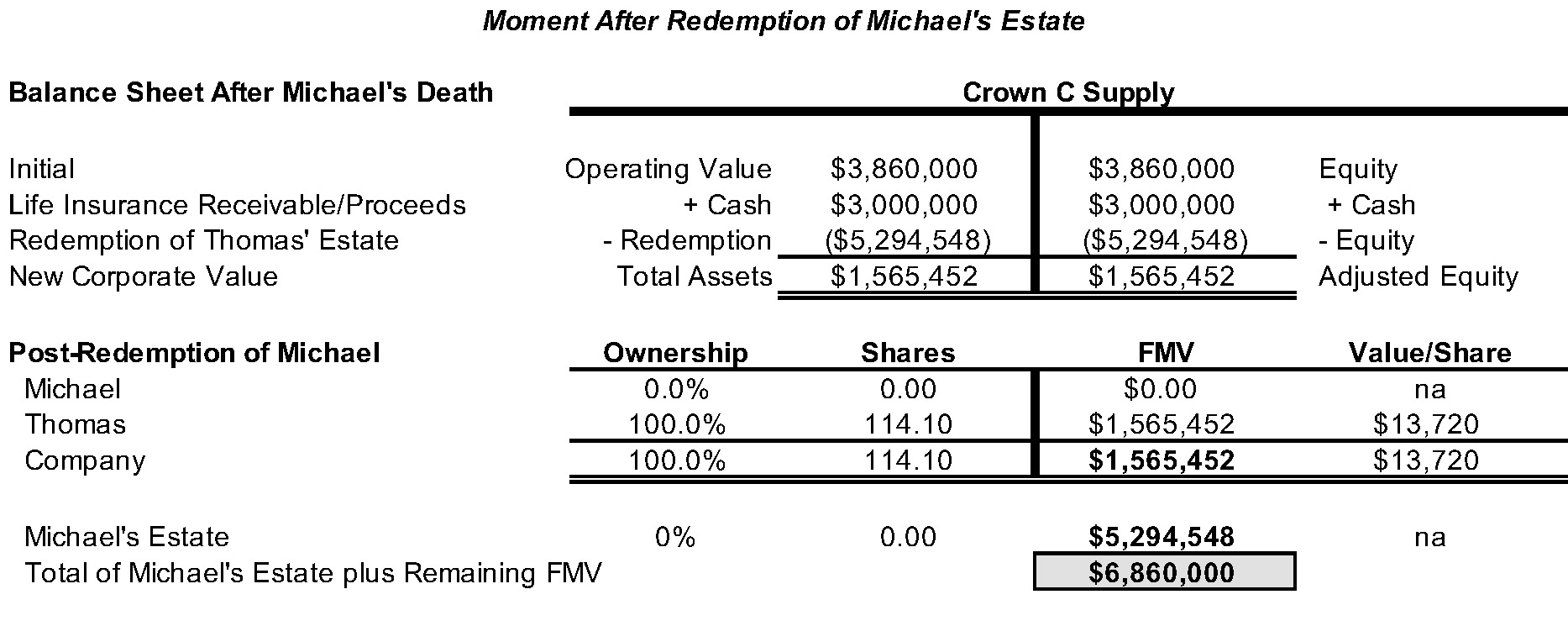

The implicit assumption behind this reasoning is that the value of Crown was $6.86 million before the redemption. However, the fair market value of Crown was $3.86 million before Michael’s death. We finish the example in Figure 4.

The problem is that Crown was not worth $6.86 million until the moment after Michael’s death. However, it was only after his death that the life insurance receivable, which was a contingent asset, available to Crown came into being. And after his death, the contingent liability to redeem his shares was also triggered.

In Figure 4, the redemption, given the new value of $6.86 million, did reduce the value of Crown by $5,298,548, or Michael’s share of that value. Thomas, on the other hand, experienced an increase in value from before Michael’s death ($880,852, or $7,720 per share) to the post-redemption value of $1,565,452, or $13,720 per share. His value increased because he benefited from his 22.82% of the life insurance proceeds (22.82% x $3,000,000) of $684,600. When this is added to his original value of $880,852, his post redemption value is $1,565,452, and his ownership rose from 22.18% to 100% because of the redemption of Michael’s shares.7

Figure 4

Click here to expand the image above

SCOTUS treated the life insurance on Michael’s life as a corporate asset and essentially assumed that this asset was available to the shareholders, while ignoring the contingent liability that Crown had to redeem Michael’s shares.

Presumably, Crown would have to use existing assets of $2.3 million (or borrow funds) to achieve the redemption. This would leave the Company in an undercapitalized state post-redemption with only $1.565 million of capital because the life insurance proceeds were included in the value of the Company. This is precisely the situation that the life insurance proceeds were supposed to have precluded.

Michael’s Estate Treated Life Insurance as a Funding Vehicle

For clarity, we repeat the initial position of Crown before Michael’s death in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Click here to expand the image above

Crown was stated to have a fair market value of $3.86 million, divided between the shareholders as discussed previously and shown in Figure 5. Upon Michael’s death, the life insurance policy was triggered, and Crown had a receivable and then proceeds of $3.0 million.

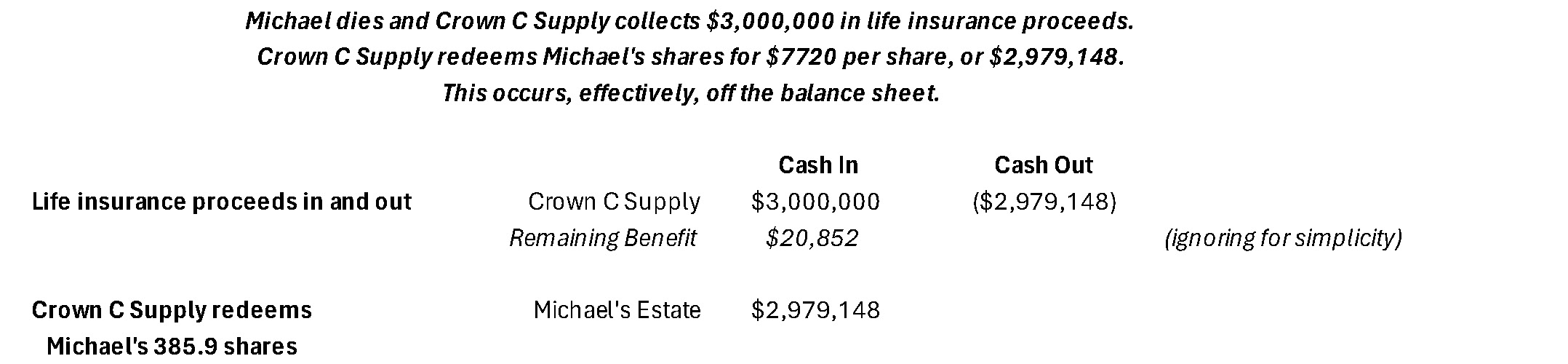

Simultaneously, Crown’s contingent liability to redeem Michael’s shares was triggered. What happens, essentially, happens off-balance sheet, as seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6

Click here to expand the image above

At this point, we see that both the contingent asset (life insurance proceeds) and the contingent liability (to purchase Michael’s shares) are used to offset each other. This is how well-written buy-sell agreements have operated for many years. There is most often an appraisal process to determine fair market value, but this was ignored by Michael’s estate and Thomas.

Crown received $3.0 million of proceeds and paid out $3.0 million to satisfy the matching liability.

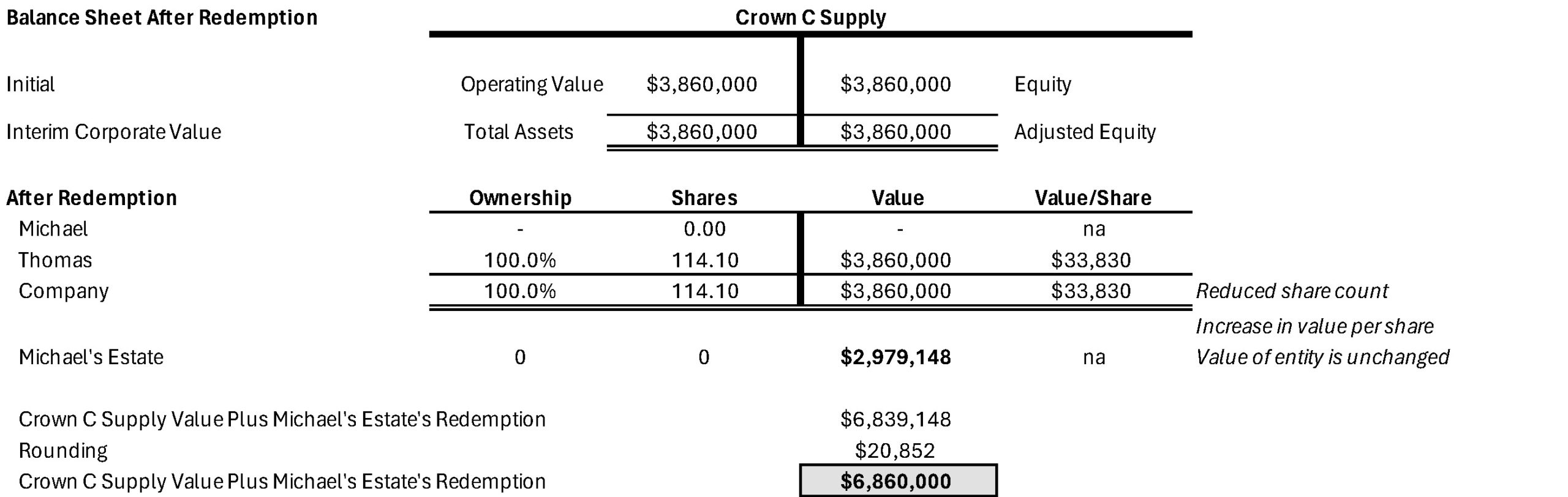

We now examine the impact of these off-balance sheet transactions on Crown, Michael’s estate, and Thomas, as the remaining owner, in Figure 7.

Figure 7

Click here to expand the image above

Reading the Eighth Circuit’s opinion on Connelly and now the SCOTUS opinion, the judges and justices seemed to think there was some skullduggery on the part of Crown and Michael’s estate. There was not. What the parties were guilty of was not following their own procedures. They did not have a certificate of value to establish the price for Michael’s redemption, as their agreements called for.

Then, when Thomas did not purchase Michael’s shares, the parties did not follow the valuation process called for in their buy-sell agreement. They cobbled together a non-independent valuation.

Had Thomas, Crown, and Michael’s estate followed their own planning, the overall result could have been significantly different.

A part of the quotation above from the “Syllabus” to the SCOTUS opinion is repeated for emphasis.

Thomas’s argument that the redemption obligation was a liability also cannot be reconciled with the basic mechanics of a stock redemption. He argues that Crown was worth $3.86 million before the redemption, and thus, that Michael’s shares were worth approximately $3 million ($3.86 million x 0.7718). But he also argues that Crown was worth $3.86 million after Michael’s shares were redeemed. See Reply Brief 6. Both cannot be right. A corporation that pays out $3 million to redeem shares should be worth less than before the redemption. (bold emphasis added)

As shown here previously, Crown could, in fact, be worth $3.86 million before the redemption of Michael’s shares for $3.0 million and after the redemption, as well. Crown received $3.0 million in life insurance proceeds (the contingent asset) that were used to satisfy the redemption of Michael’s shares (the contingent liability).

There is a similar analysis of the two treatments of life insurance for buy-sell agreements in Buy-Sell Agreements for Closely Held and Family Business Owners.8

Closing Observations

The estate planning world is keenly focused on the SCOTUS decision in Connelly. Does the decision render entity-purchased life insurance useless, or at least, less useful than before? In the short time since the decision was rendered, much has been written and said about the impact of the decision.

Readers of this article will need to examine that literature in the context of future planning for buy-sell agreements and for the reexamination of existing agreements. It is too soon to tell the ultimate impact of this important decision.

ENDNOTES

-

Estate of Blount v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue Service (2005), United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh Circuit, No. 04-15013, October 31, 2005.

-

Connelly, as Executor of the Estate of Connelly v. United States, No. 21-3683 (8th Cir. 2023), decision rendered June 2, 2023.

-

Connelly v. United States, Memorandum and Order, page 21, September 2021. It is clear from all the decisions that no court considered Thomas to be a business appraiser, regardless of his “experience.”

-

Connelly, as Executor of the Estate of Connelly v. United States, No. 21-3683 (8th Cir. 2023), decision rendered June 2, 2023.

-

Mercer, Z. Christopher Mercer, Buy-Sell Agreements for Closely Held and Family Business Owners (Memphis, Peabody Publishing, LLC, 2010)

-

Connelly v. United States, No. 23-146, Syllabus at 2-3 (U.S. June 6, 2024). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/23-146_i42j.pdf.

-

Given the timing of things, Crown turned out better off than the example. Crown received $3.0 million in life insurance proceeds and paid $3.0 million for Michael’s stock. The net worth of the Company after the redemption was $3.86 million. Recall that Michael’s estate paid $0.9 million in estate taxes. It would appear that Michael’s estate received $3.0 million for his shares of Crown. The estate also paid the additional interest demanded by the Internal Revenue Service. That tax was $889,914. The net effect is that Michael’s estate paid taxes on $5,294,548 of value, received $3.0 million for his shares, and had net assets after tax of $2.1 million. The net result is that Crown retained the $2.3 million of extra consideration that the case says it should have paid, leaving the Company with a net worth of $3.86 million ($1.565 million + $2.295 million. The real loser in all this was Michael’s estate.

-

Ibid, Chapter 15.