What Is the Value of My Auto Dealership?

It Depends on Who's Buying

In our Valentine’s Day-themed Levels of Value Blog Series, we discuss the theoretical considerations of the three distinct levels of value and how they apply to auto dealerships. In this post, we take a more practical approach to the discussion. When dealers ask themselves, “What is my auto dealership worth?” the answer is, “It depends on who’s buying.”

Three Types of Buyers

For an auto dealer, there are three primary types of buyers to consider:

- Strategic buyer – another regional or national auto group looking to add scale and take advantage of synergies. Lithia is a good example, as the company has grown to the largest auto group from its aggressive acquisition pace in recent years. But groups of varying sizes are increasingly investing in their retail footprint, looking to add more rooftops.

- Financial buyer – an investor intrigued by the attractive returns historically provided by automotive retail. Private equity is the most realistic buyer at this “level of value,” but this has become less true as private equity groups seek to make platform investments, where their principals add value based on their industry expertise rather than simply taking a rigid cost control and creative financing (i.e., taking on a bunch of debt).

While the value that a financial buyer would pay is the most straightforward answer to the true value of a dealership, or “fair market value” in valuation speak, it may also be the least common or “practical” indication of value. Why is the most realistic value the least common in real-world transactions? Most dealers hope to sell their controlling interest to a strategic buyer for the highest possible price (#1 above). And the buyer of a minority interest hopes to pay a lower price due to the lack of prerogatives of control (#3 below).

- Minority interest buyer – in practical terms, this is typically a GM with whom ownership wants to align economic interests. We’ve been involved with various engagements where, unfortunately, this relationship has become litigious. However, there are many good reasons to consider allowing a GM to buy into your dealership, and we’ve helped both parties determine a “fair” price for a non-controlling position in the dealership. We’ll discuss this more below, but whether or not to apply a discount, and the magnitude of this discount, largely depends on the agreement terms at the buy-in, and both sides should be clear about expectations.

Control Premium

In valuation theory, the price a strategic buyer is willing to pay above the fair market value of the auto dealership is called a strategic control premium. Like all indications of value, this premium is based on three key inputs: cash flows, risk, and growth.

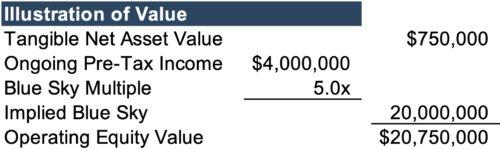

To determine a control premium, we first have to develop the “base” value to which we add the premium. As an example, let’s consider a dealership whose ongoing pre-tax income is anticipated to be $4 million. Let’s further assume that 5.0x is a reasonable Blue Sky multiple for the franchise, given its historical operating performance, particularly as it relates to its regional peers. Adding the implied Blue Sky Value to $750,000 in tangible net assets, the equity value of the dealership would be $20.75 million.

Now, let’s assume the opportunity is shown to numerous potentially interested parties, and there’s healthy interest in the dealership. Suppose the auto group seeking to buy the dealership already has its management team in place. In that case, it’s possible the selling dealer’s roles and responsibilities can be handled by someone already in-house. Assuming other synergies, we have an expected $4.3 million in ongoing pre-tax earnings expectations for the highest bidder, or a 7.5% increase.

In valuation, multiples are functions of expectations for risk and growth. Specific to auto dealers, Blue Sky multiples are a function of the dealership’s market (size and population demographics and trends, brand fit, high/low level of competition) and other factors, including taxes and real estate costs. Other company-specific considerations may be less prevalent or less of an unknown, as buyers likely know what to expect when buying different franchises.

For this example, the buyer sees less risk and/or higher growth than the seller. The buyer could be overly concentrated in domestic brands, or have numerous dealerships in the same metropolitan area, so adding an import brand in an adjacent market reduces risk through diversification. The highest bidder may also just be whoever is the most bullish on the industry’s long-term prospects, particularly in light of concerns around changes to the franchise model.

Let’s assume the buyer-specific factors lead them to pay a higher multiple of 5.5x or a 10% increase above the multiple a financial buyer might pay. As demonstrated below, the total strategic control premium is 17.6%.

This is a basic example of how your auto dealership might be more valuable to someone else. Unlike publicly traded companies, however, the value to which the strategic control premium would be applied doesn’t exist. Therefore, it really comes down to who’s willing to pay the most for the dealership.

Discount for Lack of Control or Marketability

On the other end, let’s consider a GM buying into a dealership. We typically see this somewhere between a 5-25% equity interest for GMs or other key employees. Whether or not a discount for lack of control/marketability is applicable can be defined under the standard of value and negotiated directly between the parties, specifically with an eye toward how a potential future buy-out would be structured.

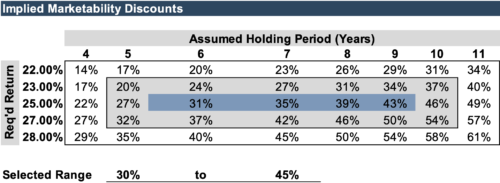

If a discount for lack of marketability (“DLOM”) is applicable based on the characteristics of the ownership, appraisers should consider both qualitative and quantitative factors when determining the discount. Qualitative assessments and historical benchmark ranges for a discount for lack of marketability typically range between 25%-45%. However, it is crucial to consider the specific investment characteristics of your dealership to understand how much of a discount it might be reasonable to offer to a buyer.

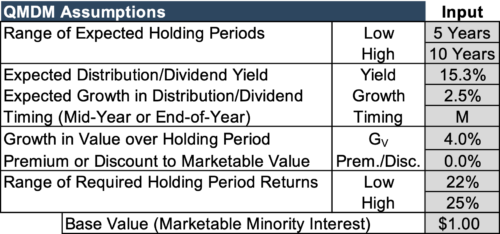

The DLOM is primarily based on the expected holding period of the investment, growth in value of the dealership during the holding period, and interim distributions. For example, let’s say there are no plans to sell the dealership in the next 5-10 years, and no material increase in value is anticipated (think Blue Sky multiple increasing from 5x to 8x). Further, the auto dealership is not planning to invest significantly in other rooftops or adjacent industries. Instead, a significant amount of income is expected to be paid out.

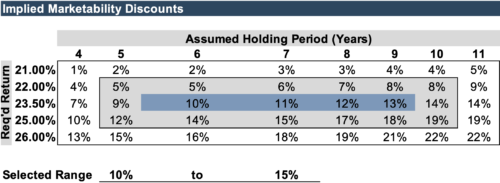

Our DLOM analysis typically considers the Quantitative Marketability Discount Method (“QMDM”). Using some reasonable assumptions (see the assumptions table below) and the case outlined above, the range of marketability discounts might be 5-20%.

We note that distributing all of the business’s earnings has a significant impact. While this leads to less growth, it means more interim distributions for the shareholders, which in this case, have a greater impact on the DLOM. Contrast this to an investment in a PE fund that doesn’t pay dividends for 7-10 years. While investors hope the lack of distributions will lead to a greater exit price, the inherent risk and lack of interim cash to invest in other ventures typically lead to higher marketability discounts.

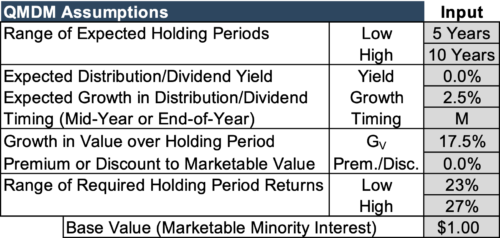

As a follow-up example to show the sensitivity, let’s instead assume that no distributions are paid, with cash flows reinvested in buying more dealerships.

Hopefully, these two examples demonstrate how significant assumptions surrounding distribution and reinvestment policy can influence the marketability of a non-controlling interestThis is particularly true for auto dealerships that have historically generated strong cash flows, especially compared to the values at which franchises tend to transact in the marketplace. GMs may exert control over day-to-day operations, but strategic decisions made by controlling ownership can significantly impact the value of the minority interest.

When determining the purchase price for a minority buy-in (or buy-out), all parties must understand what should be expected. Additionally, we encourage well-drafted buy-sell agreements that spell out the terms both for buying and selling minority interests, so nobody feels aggrieved if the buy-in and buy-out occur at different levels of value.

Conclusions

Mercer Capital provides business valuation and financial advisory services, and our auto team assists dealers, their partners, and family members in understanding the value of their auto dealerships and related entities. Contact a member of the Mercer Capital auto dealer team today to learn more about the value of your dealership.

Auto Dealer Valuation Insights

Auto Dealer Valuation Insights