Do Win/Loss Records Affect Major League Baseball Revenues and Attendance?

Many people believe that the win/loss ratio doesn’t have much effect on revenues and attendance. They believe the local team has loyal fans who will attend games despite their performance. We investigate that assumption in this article focusing on Major League Baseball (MLB) by sampling a top tier, middle tier, and lowest tier team.

We analyze average season attendance of the league over the last five years and then track the three-team sample’s attendance and on-field performance.

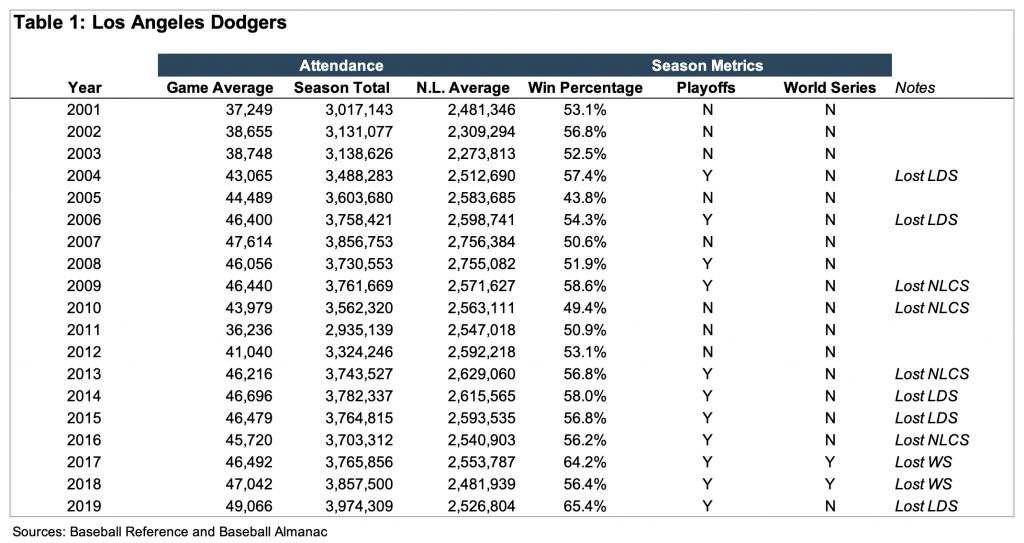

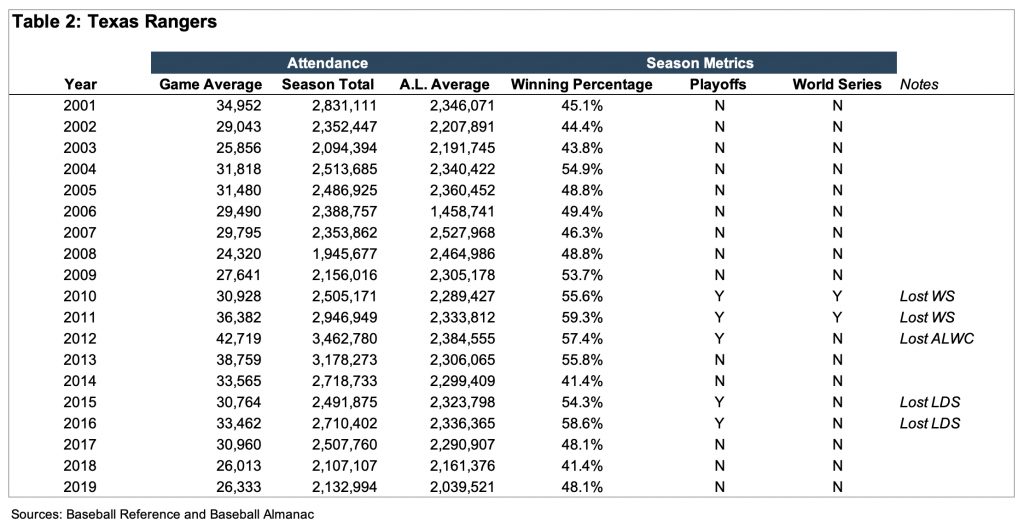

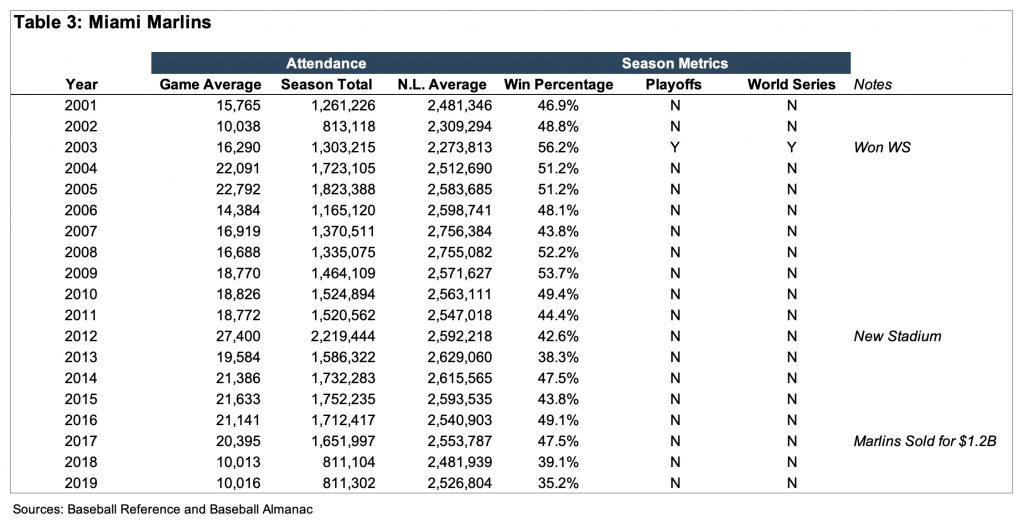

We have selected three teams to review their attendance vs. winning percentage, along with their playoff and World Series performance. Our sample consists of the Los Angeles Dodgers, the Texas Rangers and the Miami Marlins.

As a reference point, average season attendance for the MLB reached a peak in recent years at 2.5 million in 2007 for the American League and 2.8 million for the National League. The MLB averages dropped in the subsequent years and were finally steady around 2.3 million for the A.L. and 2.5 million for the N.L. during the next ten years. League attendance average declined, however, by 140,000 to 2,161,376 in 2018 and 2,039,521 in 2019.

Los Angeles Dodgers

The Dodgers attendance in 2007 was 3.9 million and stayed above 3.4 million for three years. This figure dropped to 2.9 million in 2011 yet returned to 3.7 million by 2013. Recently, season attendance has slowly climbed to approximately 4 million in 2019, marking an all-time team high.

This growth was greatly influenced by the Dodgers being in the World Series in 2017 and 2018, which helped push 2019 to a record high attendance. (See Table 1 for details)

Texas Rangers

The Texas Rangers have experienced a different attendance history. They peaked in 2012 at 3.5 million after playing in the World Series in 2011 and the playoffs in 2012. The team didn’t make the playoffs in 2013 and 2014 and attendance dropped to 3.2 million and 2.7 million, respectively. The win/loss record dropped significantly from about 59% in 2011 to 41% in 2014.

Attendance followed the same trend by dropping 450,000 to 2.7 million in 2014. Even when the team made the playoffs in 2015, attendance fell to 2.5 million as a result of their poor record in 2014. The team’s 2015 win/loss ratio was near 59% and they made the playoffs, but not the World Series. In the following year, attendance increased to 2.7 million. The win/loss ratio dropped below 50% in 2017 to 2019 and they missed the playoffs each year. As a result, attendance dropped steadily to 2.1 million in 2019, a decrease of over 1.3 million people, or 38% from their peak in 2012. (SeeTable 2 for details)

Miami Marlins

The Miami Marlins clearly represent the bottom tier of the MLB in many categories. They built a brand-new state of the art ballpark in 2012 and attendance averaged about 1.7 million from 2014 to 2017. In the fall of 2017, the Derek Jeter group bought the team. and the new owners quickly traded notable high-priced players to other teams, including the NY Yankees, in order to reduce their losses. The new ownership group was hoping to stabilize attendance near the 1.7 million mark, but instead dropped to 811,000 in both 2018 and 2019; 367,000 less than the next worst attendance in MLB, which was Tampa Bay, and about 500,000 less than the third worst team, the Baltimore Orioles. (SeeTable 3 for details)

Conclusion

Without attempting to do a statistical analysis, what does the data mean? Yes, the quality of the players counts – especially if the win/loss record corresponds, however, winning percentage also impacts the ability to get into the playoffs and ultimately the World Series. It is clear from our experience and from the three-team sample that win/loss ratios have a major effect on MLB home stadium attendance.

In Game Leaders Esports Summit Insights

The In Game Leaders (IGL) Winter Summit took place January 3, 2020 at the esports Stadium Arlington. IGL originated as a capstone project for summer interns at esports Stadium Arlington. The primary purpose of the Summit was to “[provide] the opportunity to learn from industry professionals and collegiate leaders as they speak about the various career paths in esports. IGL strives to teach parents and students how to develop a sustainable career in the rapidly-growing esports field.”

This second event (the first Summit was held on August 19, 2019) consisted of several panels that addressed collegiate esports, professional esports, as well as marketing and event management. The event drew approximately 150 people. We recap a few key panels below.

Collegiate Esports Panel

Alex Rocha (UT Arlington), Eric Aaberg (UT Dallas), Austin Espinoza (UT), Dylan Wray (UNT)

Traditional sports and esports at the collegiate level share some similarities. For example, not only do the teams practice and compete, but they workout and train in order to play to their potential. The players are one piece of the team, as there are also managers, coaches, and streamers that add value to the organization. Several universities across the country offer partial and full scholarships. As of December 2019, there were over 125 schools around the United States with esports programs.

Collegiate esports programs generally fall into two categories: club or varsity. Varsity esports programs enjoy the administrative and financial support of their educational institution while club esports organizations are student-run and have limited financial backing from their educational institution. The primary goal of most collegiate esports clubs is to become a varsity sport at their school.

A distinction between esports and traditional sports stems from the recruiting platform. In collegiate esports, recruiting currently consists of attracting students who are already on campus as opposed to recruiting from high schools. Although the recruiting landscape is less structured than in traditional sports, esports teams have had success in gaining interest from active students.

The main games played in collegiate esports include: Overwatch, League of Legends, Rocket League, Hearthstone, Super Smash Brothers, and Call of Duty. The teams encourage the gaming community on campus to join the organization, whether it be as an analyst, coach, or player. The teams emphasize that there is a position for everyone and that a student does not have to be the best at every game to bring value and compete.

Professional Esports Organizations

Kyle Bautista (COO, Complexity), Hector Rodriguez (CEO, NRG/Huntsmen), Mike Rufail (Founder/CEO, Envy)

The esports industry is turning heads and opening eyes as it becomes compared to the traditional sports leagues. The panelists, often recognized as leaders in the industry, emphasized their passion for the rapidly growing esports space. They highlighted that because esports is relatively new, and because games have shorter shelf lives, it is harder to gain significant experience.

esports is categorized as a sector in the media and entertainment industry because it is able to capitalize on the vast audience that is watching or streaming. The panelists each recalled their favorite esports events, and all described those events as having the same euphoric feel as a traditional sports game. The crowd erupts for clutch play in a Call of Duty World Championship the same as a huge play in a Super Bowl. Each panelists has been a part of the evolution of the space and all see it heading in the right direction with time.

The franchise model that has developed in traditional sports has made its way to the esports platform. The industry is attempting to follow the blueprint of the major professional sports leagues. The industry leaders agreed that the structure is beneficial, but also emphasized that time, competition, and the willingness to learn and collaborate will take esports to the next level.

Keynote Speakers

Simon Bennett and Markel Lee (AOE Creative)

As the esports industry experiences rapid growth, it is important for teams and companies to consider their brand identity. Bennett and Lee illustrated the struggles that companies within the industry often face when attempting to establish a brand or marketing initiative. Rather than simply making a brand logo that looks “cool,” Bennett and Lee challenge players in the industry to create a brand that captures the message they are attempting to create.

Simply put, “Do not build a brand, build a legacy.” – Markel Lee

Bennett and Lee were excited about the power of community marketing. Community marketing enables a vast audience to connect and establish a relationship with the message or objective that is being conveyed. The example given was the Marshmello Fortnite concert – the most attended concert in history. The concert was able to be seen by the virtual community that was playing Fortnite at the time of the event. This brilliant marketing scheme was able to capture over 10 million players at once.

Marketing and Event Management

Kyle Stephenson (Gearbox), John Davidson (PRG), Justin Varghese (Dreamhack)

Stephenson, Davidson, and Varghese explained the challenges and satisfactions of creating events in the esports space. With sponsorships providing the biggest source of revenue in the industry, events are extremely important to execute well. Creating a debut event or launching a new destination is a complicated process that takes exceptional diligence both before and after it occurs. In order to measure the success of the event, it is important to first set expectations. The three panelists agreed that expectations must be accurate going into an event.

Attracting a digitally native audience can be difficult, but it requires creating a “fear of missing out” (FOMO) in order to capture as many people as possible. For those unable to attend the first event, attracting them to the second event is also important.

A specific industry challenge is that most esports do not have a defined end. With no set run-time for most games, event managers must be prepared for every scenario. There can also be challenges that arise at an event such as power outages, which causes a delay in the audience’s experience. Putting the challenges aside, the key to executing a successful event is creating a fair and pure playing environment and enjoyable fan experience by providing an exceptional experience to as many people as possible.

Conclusion

The second IGL Summit built upon the success of the first. There was increased attendance and intriguing panel discussions. The overarching theme communicated by the panelists was that as an industry, esports is still developing. Due to the relative immaturity of the industry, best practices are not concrete and player movement mechanisms are nebulous. However, there was a general sense of optimism for the industry. esports has made great strides over the past few years but still has plenty of room to grow. According to an article by Syracuse University, the number of projected esports viewers in the U.S. will reach 84 million in 2021, second only to the NFL. There has been an increase in transactions within the industry as well with one esports organization acquiring another for approximately $100 million.

Quality Of Earnings Study: The “Combine” to Help Harvest Top FinTech Acquisition Targets

As we find ourselves at the end of the decade, many pundits are considering what sector will be most heavily influenced by the disruptive impact of technology in the 2020s. Financial services and the potential impact of FinTech is often top of mind in those discussions. As I consider the potential impact of FinTech in the coming decade, I am reminded of the Mark Twain quote that “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.”

A historical example of technological progress that comes to mind for me is the combine, a machine designed to efficiently harvest a variety of grain crops. The combine derived its name from being able to combine a number of steps in the harvesting process. Combines were one of the most economically important innovations as they saved a tremendous amount of time and significantly reduced the amount of the population that was engaged in agriculture while still allowing a growing population to be fed adequately. For perspective, the impact on American society from the combine’s invention was tremendous as roughly half of the U.S. population was involved in agriculture in the 1850s and today that number stands at less than 1%.

As I ponder the parallels between the combine’s historical impact and FinTech’s potential, I consider that our now service based economy is dependent upon financial services, and FinTech offers the potential to radically change the landscape. From my perspective, the coming “combine” for financial services will be not from one source or solution, but from a wide range of FinTech companies and traditional financial institutions that are enhancing efficiency and lowering costs across a wide range of financial services (payments, lending, deposit gathering, wealth management, and insurance). While this can be viewed as a negative by some traditional incumbents in the space, it may be a saving grace as we start the decade with the lingering effects of a prolonged historically low and difficult interest rate environment, and many traditional players are still laden with their margin dependent revenue streams and higher cost, inefficient legacy systems. Similar to the farmers adopting higher tech planting and harvesting methods through innovations like the combine, traditional incumbents like bankers, RIAs, and insurance companies will have to determine how to selectively build, partner, or acquire FinTech talent and companies to enhance their profitability and efficiency. Private equity and venture capital investors will also continue to be attracted to the FinTech sector given its potential.

As the years in the 2020s march on, FinTech acquirers and traditional incumbents face a daunting task to evaluate the FinTech sector. Reports vary but generally indicate that over 10,000 FinTechs have sprouted up across the globe in the last decade and separating the highly valued, high potential business models (i.e, the wheat) from the lower valued, low potential ones (i.e., the chaff) will be challenging. Factor in the complicated nature of the regulatory/compliance overlay and investors, acquirers, and traditional incumbents face the daunting task of analyzing the FinTech sector and the companies within it.

As a solution to this potential problem, the efficient operations and historical lessons learned in the agricultural sector from the combine may again provide insights for buyers of FinTech companies to learn from. For example, the major professional sports leagues in the U.S. all have events called combines where they put prospective players through drills and tests to more accurately assess their potential. In these situations, the team is ultimately the buyer or investor and the player is the seller. Pro scouts are most interested in trying to project how that player might perform in the future for their team. While a player may have strong statistics in college, this may not translate to their future performance at the next level so it’s important to dig deeper and analyze more thoroughly. For the casual fan and the players themselves, it can be frustrating to see a productive college player go undrafted while less productive players go highly drafted because of their stronger performance at the combine.

While not quite as highly covered by the fans and media, a similar due diligence and analysis process should take place when acquirers examine a FinTech acquisition target. This due diligence process can be particularly important in a sector like FinTech where the historical financial statements may provide little insight into future growth and earnings potential for the underlying company. One way that acquirers are able to better assess potential targets is through a process similar to a sports combine called a quality of earnings study (QoE). In this article, we give a general overview of what a QoE is as well as some important factors to consider.

What is a Quality of Earnings Study? A QoE study typically focuses on the economic earning power of the target. A QoE combines a number of due diligence processes and findings into a single document that can be vitally helpful to a potential acquirer in order to assess the key elements of a target’s valuation: core earning power, growth potential, and risk factors. Ongoing earning power is a key component of valuation as it represents an estimate of sustainable earnings and a base from which long term growth can be expected. This estimate of earning power typically considers trying to assess the quality of the company’s historical and projected future earnings. In addition to assessing the quality of the earnings, buyers should also consider the relative riskiness of those earnings as well as potential pro-forma synergies that the target may bring in an acquisition.

Analysis performed in a QoE study can include the following:

- Profitability Procedures. Investigating historical performance for impact on prospective cash flows. EBITDA analysis can include certain types of adjustments such as: (1) Management compensation add-back; (2) Non-recurring items; (3) Pro-forma adjustments/synergies

- Customer Analysis. Investigating revenue relationships and agreements to understand the impact on prospective cash flows. Procedures include: (1) Identifying significant customer relationships; (2) Gross margin analysis; and (3) Lifing analysis

- Business and Pricing Analysis. Investigating the target entities positioning in the market and understanding the competitive advantages from a product and operations perspective. This involves: (1) Interviews with key members of management; (2) Financial analysis and benchmarking; (3) Industry analysis; (4) Fair market value assessments; and (5) Structuring

These areas are broad and may include a wide array of sub-areas to investigate as part of the QoE study. Sub-areas can include:

- Workforce / employee analysis

- A/R and A/P analysis

- Intangible asset analysis

- A/R aging and inventory analysis

- Location analysis

- Billing and collection policies

- Segment analysis

- Proof of cash and revenue analysis

- Margin and expense analysis

- Capital structure analysis

- Working capital analysis

For high growth technology companies where the analysis and valuation is highly dependent upon forecast projections, it may also be necessary to analyze other specific areas such as:

- The unit economics of the target. For example, a buyer may want a more detailed estimate or analysis of the some of the target’s key performance indicators such as cost of acquiring customers (CAC), lifetime value of new customers (LTV), churn rates, magic number, and annual recurring revenue/profit.

- A commercial analysis that examines the competitive environment, go-to-market strategy, and existing customers perception for the company and its products.

This article discusses a number of considerations that buyers may want to assess when performing due diligence on a potential FinTech target. While the ultimate goal is to derive a sound analysis of the target’s earning power and potential, there can be a number of different avenues to focus on, and the QoE study should be customized and tailored to the buyer’s specific concerns as well as the target’s unique situations. It is also paramount for the buyer’s team to keep the due diligence process focused, efficient, and pertinent to their concerns. For sellers, a primary benefit of a QoE can be to help them illustrate their future potential and garner more interest from potential acquirers.

Mercer Capital’s focused approach to traditional quality of earnings analysis generates insights that matter to potential buyers and sellers. Leveraging our valuation and advisory experience, our quality of earnings analyses identify and focus on the cash flow, growth, and risk factors that impact value. Collaborating with clients, our senior staff identifies the most important areas for analysis, allowing us to provide cost-effective support and deliver qualified, objective, and supportable findings. Our goal is to understand the drivers of historical performance, unit economics of the target, and the key risk and growth factors supporting future expectations. Our methods and experience provide our clients with a fresh and independent perspective on the quality, stability, and predictability of future cash flows.

Our methodologies and procedures are standard practices executed by some of the most experienced analysts in the FinTech industry. Our desire is to provide clients with timely and actionable information to assist in capital budgeting decisions. Combined with our industry expertise, risk assessment, and balanced return focus, our due diligence and deal advisory services are uniquely positioned to provide focused and valued information on potential targets.

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Value Focus: FinTech Industry Newsletter, Year-End 2019.

2020 Outlook: Good Fundamentals, Moderate Valuations but Limited EPS Growth

Bank fundamentals, which are discussed in more detail below, did not change a lot between 2018 and 2019; however, bank stock prices and the broader market posted strong gains as shown in Table 1 following a short but intense bear market that bottomed on Christmas Eve 2018. Our expectation is that 2020 will not see much change in fundamentals either, while bank stocks will require multiples to expand to produce meaningful gains given our outlook for flattish earnings.

Fed Drives the Market Rebound

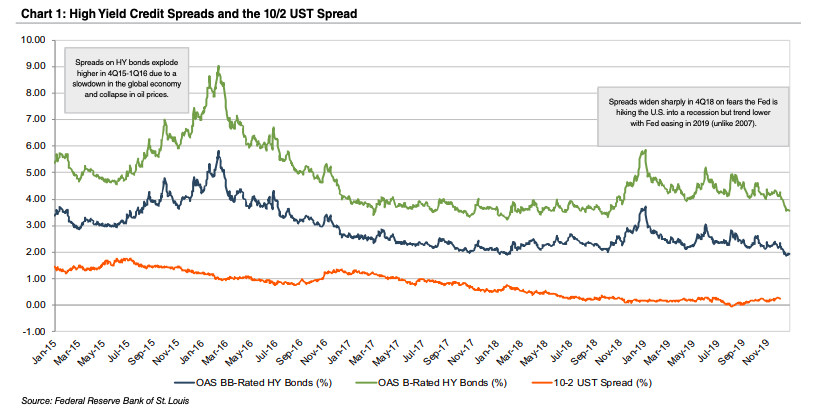

The primary culprit for the 4Q18 plunge and subsequent 2019 rebound in equity prices was the Fed, which has a propensity to hike until something breaks according to a long standing market saw. A year-ago the Fed had implemented its ninth hike in short-term policy rates that it controls despite the vocal protests of the President and, more importantly, the credit markets as reflected in widening credit spreads and falling yields on Treasury bonds and forward LIBOR rates.

One can debate how much weight the Fed places on equity markets, but it has always appeared to us that they pay close attention to credit market conditions. When the high yield bond and leverage loan markets shutdown in December 2018, the Fed was forced to pivot in January and back away from rate hikes after forecasting several for 2019 just a few months earlier. Eventually, the Fed was forced to reduce short rates three times and resume expansion of its balance sheet in the fourth quarter after halting the reduction (“quantitative tightening”) in mid-year.

Markets lead fundamentals. Among industry groups bank stocks are “early cyclicals,” meaning they turn down before the broader economy does and tend to turn up before other sectors when recessions bottom. One take from the price action in banks is that the economy in 2020 will be good enough that credit costs will not rise dramatically. Otherwise, banks would not have staged as strong a rebound as occurred.

Likewise, somewhat tighter spreads on B- and BB-rated high yield bonds relative to U.S. Treasuries (option adjusted spread, “OAS”) since the Fed eased is another data point that credit in 2020 will not see material weakening. The stable-to-tighter spreads in the high yield market today can be contrasted with 2007 when OAS began to widen sharply even after the Fed began to cut rates and the U.S. Treasury curve steepened as measured by the spread between the yield on the two-year and 10-year notes.

Bank Fundamentals

Bank fundamentals are in good shape even though industry net income for the first three quarters of 2019 increased nominally to $181 billion from $178 billion in the comparable period in 2018. On a quarterly basis, third quarter earnings of $57 billion were below the prior ($63 billion) and year ago ($62 billion) quarters. Not surprisingly, earnings pressure emerged during the year as what had been expanding NIMs during 2017 and 2018 began to contract due the emergence of a flat-to-inverted yield curve, a reduction in 30/90-day LIBOR which serves as a base rate for many loans, and continuation of a highly competitive market for deposits. Also, loan growth slowed in 2019—especially for larger institutions.

As shown in Table 2, core metrics such as asset quality and capital are in good shape, while profitability remains high. Our outlook for 2020 is for profitability to ease slightly due to incrementally higher credit costs and a lower full year NIM although stabilization seems likely during 2H20. Nonetheless, ROCE in the vicinity of 10- 11% and ROTCE of 13-14% for large community and regional banks seems a reasonable expectation.

EPS growth will be lacking, however. Wall Street consensus EPS estimates project essentially no change for large community and regional banks, while super regional banks are projected to be slightly higher at 3%. Money center banks (BAC, C, GS, JPM, MS, and WFC) reflect about 6% EPS growth, which seems high to us even though the largest banks tend to be more active in repurchasing shares relative to smaller institutions where excess capital is allocated to acquisitions, too.

The Fed—Presumably on Hold

In the December 2018 issue of Bank Watch we opined it was hard to envision the Fed continuing to raise short-term rates even though the Fed forecasted further hikes. We further cited the potential for rate cuts. Our reason for saying so was derived from the market rather than economists because intermediate- and long-term rates had decidedly broken an uptrend and were heading lower.

As the calendar turns to 2020, the Fed has indicated no changes are likely for the time being. The market reflects a modest probability that one more cut will be forthcoming, but to do so in an election year probably would require long rates to fall enough to meaningfully invert the Treasury curve unlike the nominal inversion which occurred in mid-2019.

As it relates to bank fundamentals, the impact on NIMs will depend upon individual bank balance sheet compositions. Broadly, however, a scenario of no rate hikes implies NIMs should stabilize in 2H20 as higher cost CDs and wholesale borrowings rollover at lower rates. Also, if the Fed continues to expand its balance sheet (presently it is doing so through only purchasing T-bills through support of the repo market) then assets may remain well bid. All else equal, stable to rising prices in the capital markets usually are supportive of credit quality within the banking system.

Bank Valuations—Rebound from Year-End 2018 “Bargains”

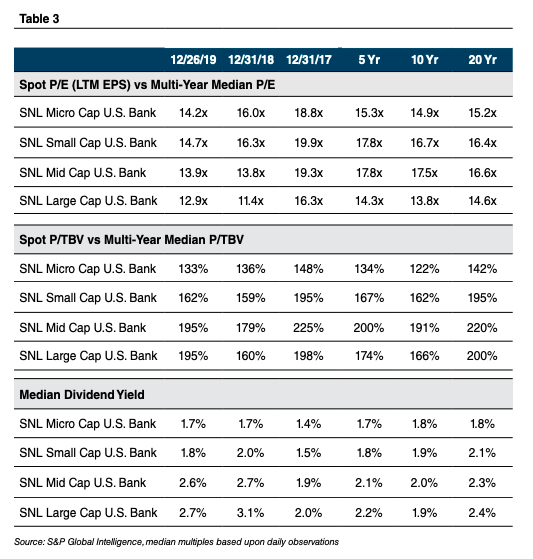

A synopsis of bank valuations is presented in Table 3 in which current valuations for the market cap indices are compared to year-end 2018 and year-end 2017 as well as multi-year medians based upon daily observations over the past 20 years.

The table illustrates the important concept of reversion to the mean. Valuations were above average as of year-end 2017 due to policy changes that occurred with the November 2016 national elections that culminated with the enactment of corporate tax reform in late 2017. One year later valuations were “cheap” as a result of the then bear market that reflected concerns the Fed would hike the U.S. into a recession.

Despite the rebound in prices and valuation multiples during 2019, bank stocks enter 2020 with moderate valuations provided the market (and us) have not miscalculated and earnings are poised to fall sharply. Money center and super-regional banks are trading for median multiples of about 10x and 11x consensus 2020 earnings. Regional and large community banks, which include many acquisitive banks, trade for respective median multiples of 12x and 13x.

An important point is that valuation is not a catalyst to move a stock; rather, valuation provides a margin of safety (or lack thereof) and thereby can provide additional return over-time as a catalyst such as upward (or downward) earnings revisions can cause a multiple to expand or contract. Looking back to last year one might surmise the rebound in valuations reflects the market’s view that the Fed avoided hiking the U.S. into recession.

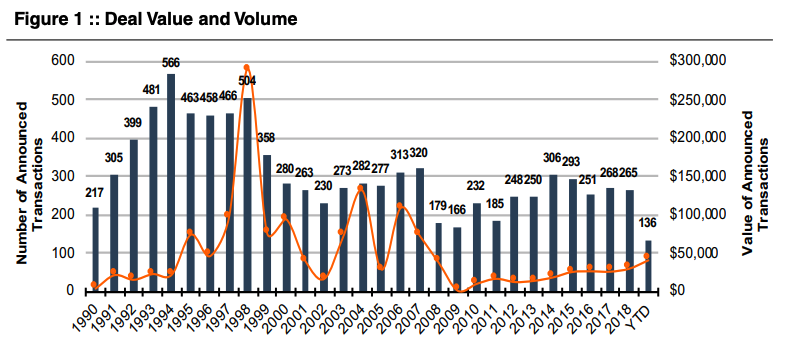

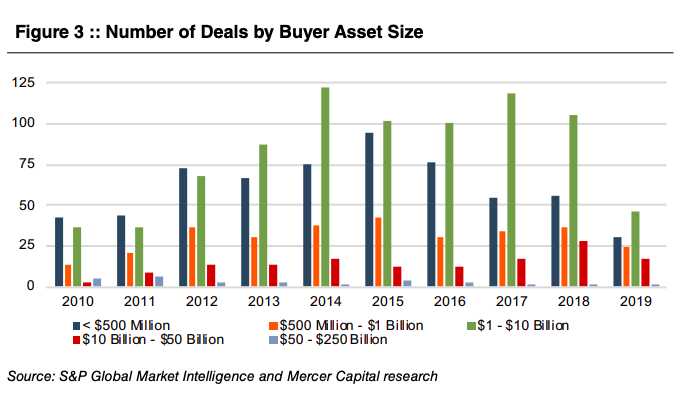

Bank M&A—2020 Potentially a Great year

M&A activity has been robust with bank and thrift acquisitions since 2014 exceeding 4% of the industry charters at the beginning of each year. It appears once the final tally is made, upwards of 275 institutions will have been acquired in 2019, which would represent almost 5% of the industry. With only a handful of new charters granted since the financial crisis the industry is shrinking fast. As of Sept. 30, there were 5,256 U.S. banks and thrifts, down from about 18,000 in 1985.

While activity was steady at a high level in 2019, the most notable development was market support for four merger-of-equals (“MOE”) in which the transaction value exceeded $1.0 billion. The largest transaction closed Dec. 9 when BB&T Corp. and SunTrust merged to form Truist Financial Corp. Others announced this year include tie-ups between TCF Financial Corp./Chemical Financial Corp., First Horizon National Corp./IBERIABANK Corp., and Texas Capital Bancshares Inc./Independent Bank Group Inc. Although not often pursued, we believe MOEs are a logical transaction that if well executed provide significant benefits to community bank shareholders.

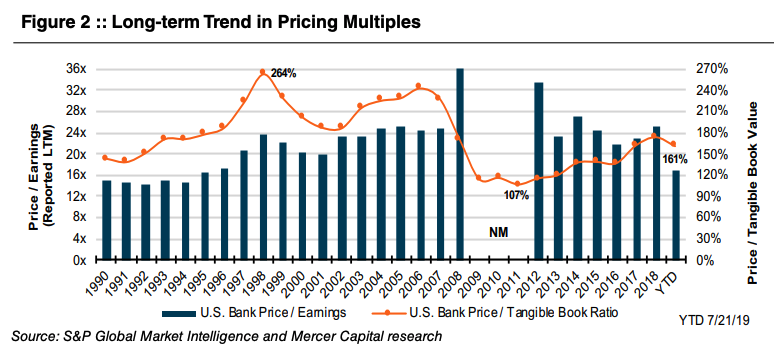

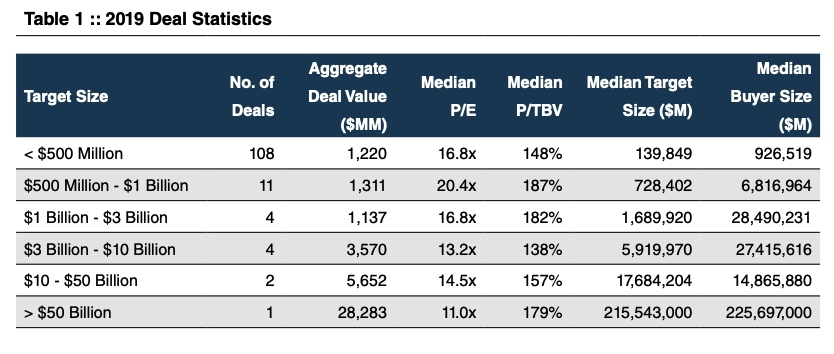

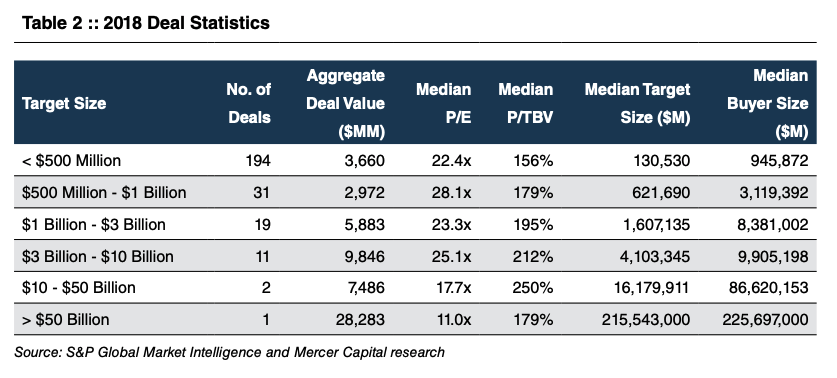

The national average price/tangible book multiple eased to 157% from 173% in 2018, while the median price/earnings (trailing 12 months as reported) declined to 16.8x from 25.4x (~21x adjusted for the impact of corporate tax reform). The reduction was not surprising given low public market valuations that existed at the beginning of 2019 because acquisition multiples track public market multiples with a lag.

We see 2020 shaping up as a potentially great year for bank M&A. The backdrop is an M&A trifecta: buyer and seller earnings will likely be flattish primarily due to sluggish loan growth and lower NIMs; asset quality is stable; and stock prices are higher, meaning buyers can offer better prices (but less value) to would-be sellers. Also, the capital markets remain wide open for banks to issue subordinated debt and preferred equity at very low rates to fund cash consideration not covered by existing excess capital.

Summing it Up

This year appears to be the opposite of late 2018 in which a strong market for bank stocks is predicting continuation of solid fundamentals and possibly better than expected earnings. Nonetheless, an environment in which earnings growth is expected to be modest at best likely will result in limited gains in bank stocks given the rebound in valuations that occurred in 2019.

Originally published in Bank Watch, December 2019.

Lessons from Recent Engagements

In our family law practice, we serve as valuation and financial forensic expert witnesses. There is typically another valuation expert on “the other side.” In several recent engagements, the following topics, posed as questions here, were raised as points of contention. We present them here to help the reader, whether you are a family law attorney or a party to a divorce, understand certain valuation-related issues that may be raised in your matter.

Should Your Expert Witness Be a Valuation or Industry Expert?

The financial and business valuation portion of a litigation is often referred to as a “battle of the experts” because you have at least two valuation experts, one for the plaintiff and one for the defendant. Hopefully your valuation expert has both valuation expertise and industry expertise. While industry expertise is not necessary in every engagement, it can be helpful in understanding the subtleties of the business in question.

Does the Appraisal Discuss Local Economic Conditions and Competition Adequately?

Most businesses are dependent on the climate of the national economy as well as the local economy. For businesses who have a national client base, the health of the national economy trumps any local or regional economy. However, many of the businesses we value in divorce engagements are more affected by changes in their local and regional economy. It’s important for a business appraiser to understand the difference and to be able to understand the effects of the local/regional economy on the subject business. There is also a fine balance between understanding and acknowledging the impact of that local economy without overstating it. Often some of the risks of the local economy are already reflected in the historical operating results of the business.

If There Are Governing Corporate Documents, What Do They Say About Value, and Should They Be Relied Upon?

Many of the corporate entities involved in litigation have sophisticated governance documents that include Operating Agreements, Buy-Sell Agreements, and the like. These documents often contain provisions to value the stock or entity through the use of a formula or process. Whether or not these agreements are to be relied upon in whole or in part in a litigated matter is not always clear. In litigated matters, focus will be placed on whether the value concluded from a governance document represents fair market value, fair value, or some other standard of value.

Two common questions that arise concerning these agreements are:

- Has an indication of value ever been concluded using the governance document in the history of the business (in other words, has the business been valued using the methodology set out in the document)?

- Have there been any transactions, buy-ins, or redemptions utilizing the values concluded in a governance document?

These are important questions to consider when determining the appropriate weight to place on a value indication from a governance document. In divorce matters, the out-spouse is often not bound by the value indicated by the governance document since they were not a signatory to that particular agreement. It is always important to discuss this issue with your attorney.

Have There Been Prior Internal Transactions of Company Stock and at What Price?

Similar to governance documents, internal transactions are a possible valuation data point. A good appraiser will always ask if there have been prior transactions of company stock and, if so, how many have occurred, when did they occur, and at what terms did they occur? There is no magic number, but as with most statistics, more transactions closer to the date of valuation can often be considered as better indicators of value than fewer transactions further from the date of valuation.

An important consideration in internal transactions is the motivation of the buyer and seller. If there have been multiple internal transactions, appraisers have to determine the appropriateness of which transactions to possibly include and which to possibly exclude in their determination of value. Without an understanding of the motivation of the parties and of the specific facts of the transactions, it becomes trickier to include some, but exclude others. The more logical conclusion would be to include all of the transactions or exclude all of the transactions with a stated explanation.

What Do the Owner’s Personal Financial Statements Say and Are They Important?

Most business owners have to submit personal financial statements as part of any guarantee on financing. The personal financial statement includes a listing of all of the assets and liabilities of the business, typically including some value assigned to the value of the business. In divorce matters, these documents are important as yet another valuation data point.

One view of the value placed on a business in an owner’s personal financial statement is that no formal valuation process was used to determine that number; so, at best, it’s a thumb in the air, blind estimate of value. The opposing view is the individual submitting the personal financial statement is attesting to the accuracy and reliability of the financial figures contained in document under penalty of perjury. Further, some would say that the value assigned to the business has merit because the business owner is the most informed person regarding the business, its future growth opportunities, competition, and the impact of economic and industry factors on the business.

For an appraiser, it’s not a good situation to be surprised by the existence of these documents. A good business appraiser will always ask for them. The business value indicated in a personal financial statement should be viewed in light of value indications under other methodologies and sources of information. At a minimum, personal financial statements may require the expert to ask more questions or use other factors, such as the national and local economy, to explain any difference in values over time.

Do You Understand Normalizing Adjustments and Why They Are Important?

Normalizing adjustments are adjustments made for any unusual or non-recurring items that do not reflect normal business operations. During the due diligence interview with management, an appraiser should ask if the business has non-recurring or discretionary expenses and are personal expenses of the owner being paid by the business? Comparing the business to industry profitability data can help the appraiser understand the degree to which the business may be underperforming.

An example of how normalizing adjustments work is helpful. If a business has historically reported 2% EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) and the industry data suggests 5%, the financial expert must analyze why there is a difference between these two data points and determine if there are normalizing adjustments to be applied. Let’s use some numbers to illustrate this point. For a business with revenue of $25 million, historical profitability at 2% would suggest EBITDA of $500,000. At 5%, expected EBITDA would be $1,250,000, or an increase of $750,000. In this case, the financial expert should analyze the financial statements and the business to determine if normalization adjustments are appropriate which, when made, will reflect a more realistic figure of the expected profitability of the business without non-recurring or personal owner expenses.

Conclusion

There are many other issues a valuation expert faces in divorce matters; however, the issues presented here were top of mind for us because they were present in recent engagements. Valuation can be complex. Serving as an expert witness can be challenging as well. However, having an expert with valuation expertise and experience is an advantageous combination in divorce matters. In future articles, we’ll discuss other issues of importance to hopefully help you become a more knowledgeable user of valuation services. In the meantime, if you have a valuation or financial forensics issue, feel free to contact us to discuss it in confidence.

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Tennessee Family Law Newsletter, Third Quarter 2019.

Community Bank Valuation (Part 4): Valuing Minority Interests

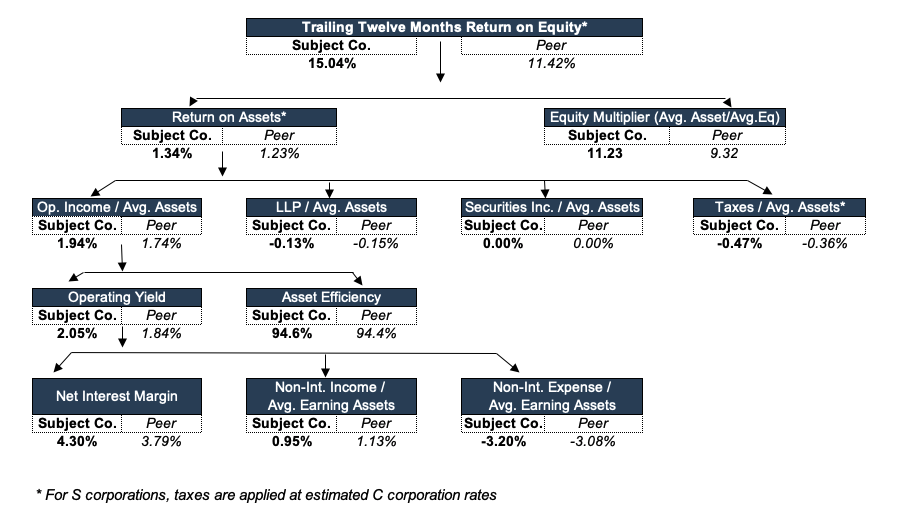

In the June 2019 BankWatch we began a multi-part series exploring the valuation of community banks. The first segment introduced key valuation drivers: various financial metrics, growth, and risk. The second and third editions described the analysis of bank and bank holding company financial data with an emphasis on gleaning insights that affect the valuation drivers. We now conclude our series by assembling these pieces into the final product, a valuation of a specific bank.

While it would streamline the valuation process, there is no single value for a bank that is applicable to every conceivable scenario giving rise to the need for a valuation. Instead, valuation is context dependent. This edition of the series focuses on the valuation of minority interests in banks, which do not provide the ability to dictate control over the bank’s operations. The next edition focuses on valuation considerations applicable to controlling interests in banks that arise in acquisition scenarios.

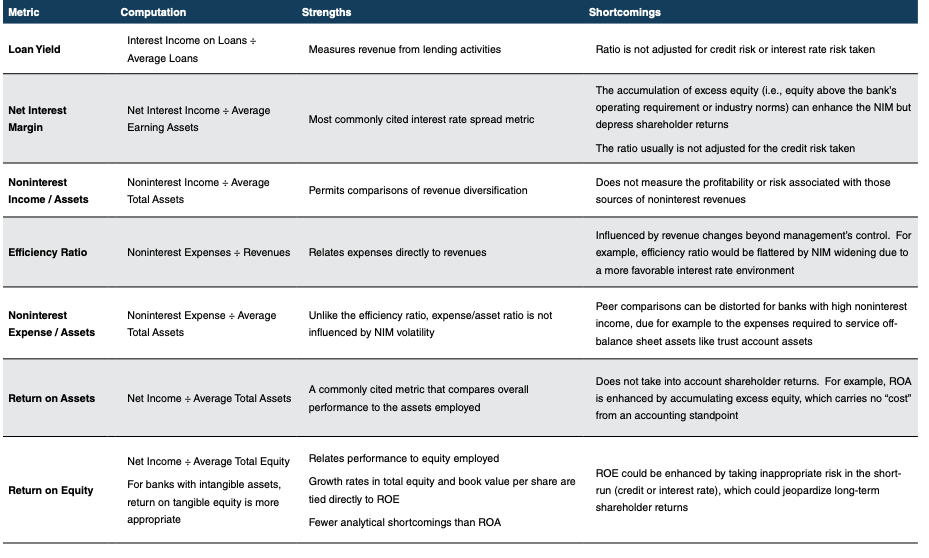

Valuation Approaches

Valuation specialists identify three broad valuation approaches within which several valuation methods exist:

- The Asset Approach develops a value for a bank’s common equity based on the difference between its assets and liabilities, both adjusted to market value. This approach is less common in practice, given analysts’ focus on banks’ earnings capacity and market pricing data. In theory, a rigorous application of the asset approach would require determining the value of the bank’s intangible assets, such as its customer relationships, which introduces considerable complexity.

- The Market Approach provides indications of value by reference to actual transactions involving securities issued by comparable institutions. The obvious advantage of this approach is the coherence between the goal of the valuation itself (the derivation of market value) and the data used (market transactions). The disadvantage, though, is that perfectly comparable market data seldom exists. While we will not cover the topic in this article, transactions in the subject bank’s common stock, which often occur for privately held banks due to their frequently widespread ownership and stature in the community, may serve as another indication of value under the market approach.

- The Income Approach includes several methods that convert a cash flow stream (such as earnings or dividends) into a value. Two broad subsets of the income approach exist – single period capitalization methods and discounted cash flow methods. For bankers, a single period capitalization is analogous to a net operating income capitalization in a real estate appraisal; it requires an earnings metric and a capitalization multiple. Alternatively, bank valuations often use projection-based methodologies that convert a future stream of benefits into a value. The strengths and weaknesses of a projection-based methodology derive from a commonality – it requires a forecast of future performance. While creating such a forecast is consistent with the forward-looking nature of investor returns, predicting the future is, as they say, difficult.

The following discussion focuses on the valuation methodologies used most commonly for banks, the comparable company method and the discounted cash flow method.

Comparable Company Method

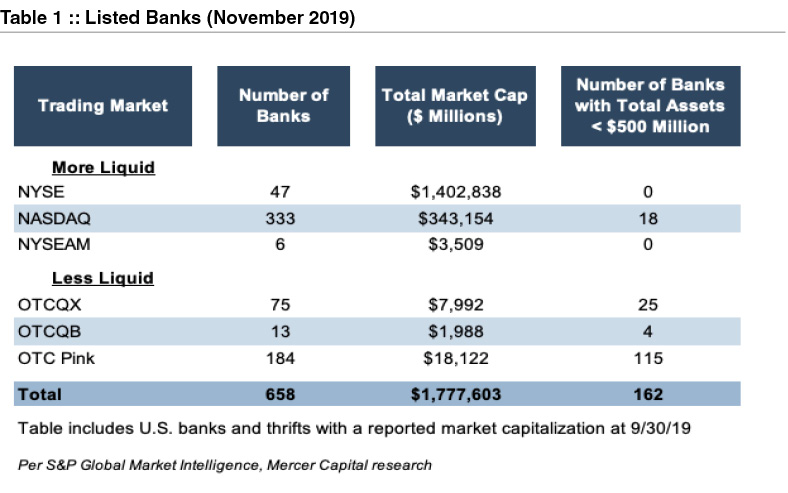

Bank analysts are awash in data, both regarding banks’ financial performance but also market data regarding publicly traded banks’ valuation. Table 1 presents a breakdown by trading market of the number of listed banks in November 2019.

To narrow this surfeit of comparable company data, analysts often screen the publicly traded bank universe based on characteristics such as the following:

- Size, such as total assets or market capitalization

- Profitability, such as return on assets or return on equity

- Location

- Asset quality

- Revenue mix, such as the proportion of revenue from loan sales or asset management fees

- Balance sheet composition, such as the proportion of loans or dependence on wholesale funding

- Trading market or volume

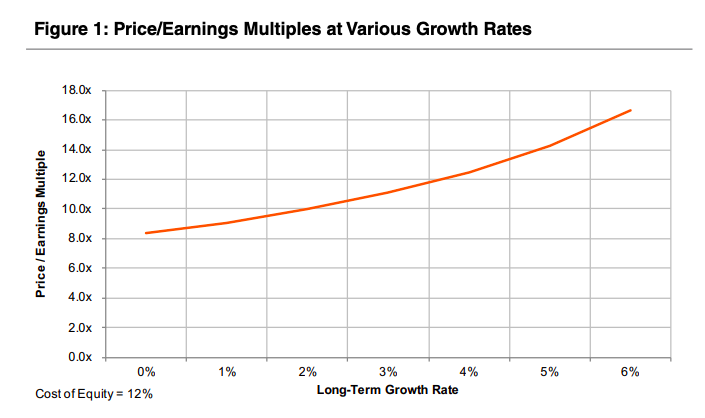

Even after applying screens similar to the preceding, it remains doubtful that the publicly traded banks will exactly mirror the subject bank’s characteristics. This is especially true when valuing smaller community banks, as a relatively limited number of publicly traded banks exist with assets of less than $500 million that trade in more liquid markets. Ultimately, the analyst must determine an appropriate valuation multiple based on the subject bank’s perceived growth opportunities and risk attributes relative to the public companies. For example, analysts can compare the subject bank’s historical and projected EPS growth rates against the public companies’ EPS growth rates, with a materially lower growth outlook for the subject bank suggesting a lower pricing multiple.

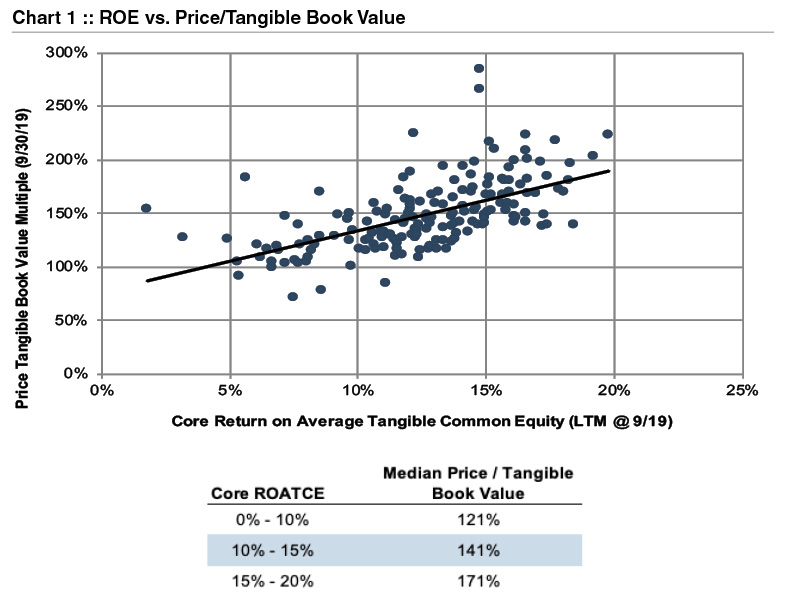

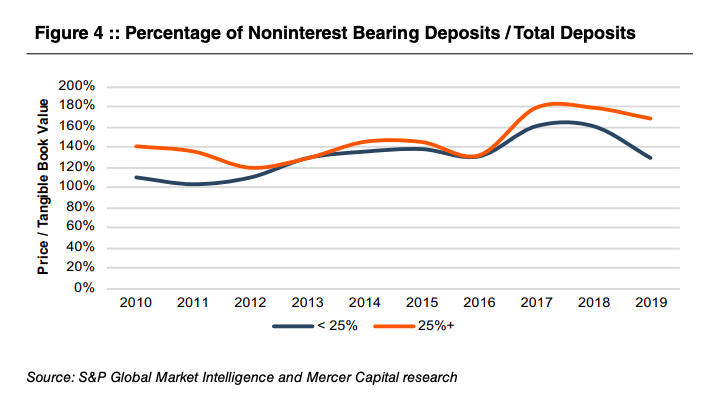

Part 1 of this community bank valuation series described various valuation metrics applicable to banks, most prominently earnings and tangible book value. It is important to reiterate that while bankers and analysts often reference price/tangible book value multiples, the earning power of the institution drives its value. Chart 1 illustrates this point, showing that price/tangible book value multiples rise along with the core return on tangible common equity. This chart includes banks traded on the NASDAQ, NYSE, or NYSEAM with assets between $1 and $10 billion.

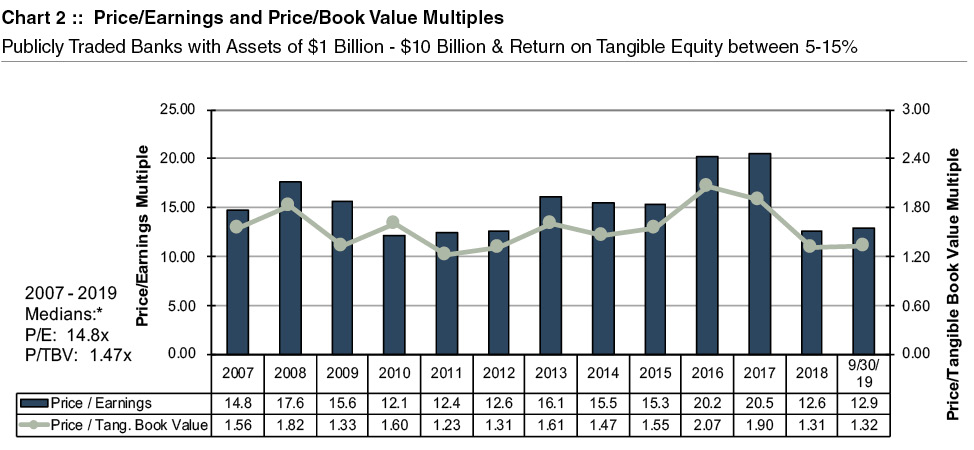

Since banking is a more mature industry, bank price/earnings multiples tend to vary within a relatively tight range. Chart 2 provides some perspective on historical price/earnings and price/tangible book value multiples, which includes banks traded on the NASDAQ, NYSE, or NYSEAM with assets between $1 and $10 billion and a return on core tangible common equity between 5% and 15%. Trading multiples in the first several years of the analysis may be distorted by recessionary conditions, while the multiples reported for 2016 and 2017 were exaggerated by optimism regarding the potential, at that time, for tax and regulatory reform. The diminished multiples at yearend 2018 and September 30, 2019 reflect a challenging interest rate environment, marked by a flat to inverted yield curve, and the possibility for rising credit losses in a cooling economy.

Discounted Cash Flow Method

The discounted cash flow (DCF) method relies upon three primary inputs:

- A projection of cash flows distributable to investors over a finite time period » A terminal, or residual, value representing the value of all cash flows occurring after the end of the finite forecast period

- A discount rate to convert the discrete cash flows and terminal value to present value

1. Cash Flow

First, a few suggestions regarding projections:

- For a financial institution, projecting an income statement without a balance sheet usually is inadvisable, as this obscures important linkages between the two financial statements. For example, the bank’s projected net interest income growth may require a level of loan growth not permitted by the bank’s capital resources.

- Including a roll-forward of the loan loss reserve illustrates key asset quality metrics, such as the ratios of loan charge-offs to loans and loan loss reserves to loans. The level of charge-offs should be assessed against the bank’s historical performance and the economic outlook.

- Key financial metrics, both for the balance sheet and income statement, should be assessed against the bank’s historical performance and peer banks.

- While projections can be prepared on a consolidated basis, we prefer developing separate projections for the bank and its holding company. This makes explicit the relationships between the two entities, such as the holding company’s reliance on the bank for cash flow. For leveraged holding companies, a sources and uses of funds schedule is useful.

In preparing a DCF analysis for a bank, the most meaningful cash flow measure is distributable tangible equity. The analyst sets a threshold ratio of tangible common equity/tangible assets or another regulatory capital ratio based on management’s expectations, regulatory requirements, and/or peer and publicly traded comparable company levels. Equity generated by the bank above this target level is assumed to be distributed to the holding company. After determining the holding company’s expenses and debt service requirements, the remaining amount represents shareholder cash flow, which then is captured in the DCF valuation analysis.

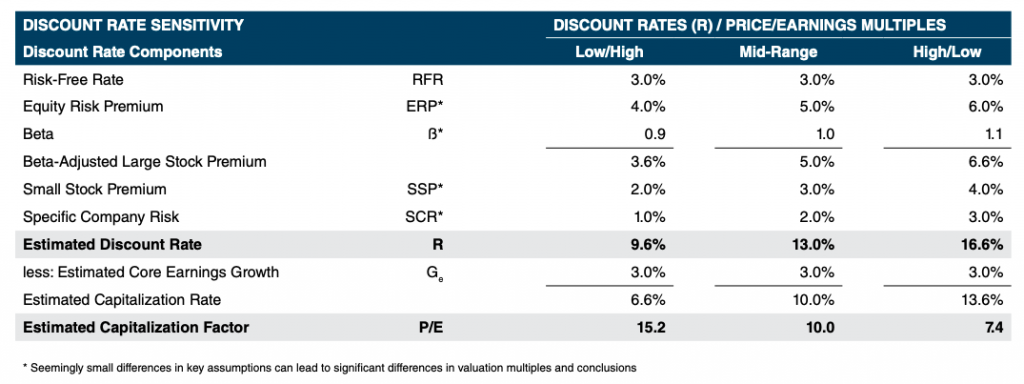

2. Discount Rate

For a financial institution, the discount rate represents the entity’s cost of equity. Outside the financial services industry, analysts most commonly employ a weighted average cost of capital (WACC) as the discount rate, which blends the cost of the company’s debt and equity funding. However, banks are unique in that most of their funding comes from deposits, and the cost of deposits does not rise along with the entity’s risk of financial distress (because of FDIC insurance). Therefore, a significant theoretical underpinning for using a WACC – that the cost of debt increases along with the entity’s risk of default – is undermined for a bank. Analytical consistency is created in a DCF analysis by matching a cash flow to equity investors (i.e., dividends) with a cost of equity.

A bank’s cost of equity can be estimated based on the historical excess returns generated by equity investments over Treasury rates, as adjusted by a “beta” metric that captures the volatility of bank stocks relative to the broader market. Analysts may also consider entity-specific risk factors – such as a concentration in a limited geographic market, elevated credit quality concerns, and the like – that serve to distinguish the risk faced by investors in the subject institution relative to the norm for publicly traded banks from which cost of equity data is derived.

3. Terminal Value

The terminal value is a function of a financial metric at the end of the forecast period, such as net income or tangible book value, and an appropriate valuation multiple. Two techniques exist to determine a terminal value multiple. First, the Gordon Growth Model develops an earnings multiple using (a) the discount rate and (b) a long-term, sustainable growth rate. Second, as illustrated in Chart 2, bank pricing multiples tend to vary within a relatively tight range, and a historical average trading multiple can inform the terminal value multiple selection.

Correlating the Analysis

In most analyses, the values derived using the market and income approaches will differ. Given a range, an analyst must consider the strengths and weaknesses of each indicated value to arrive at a final concluded value. For example, earnings based indications of value derived using the market approach may be more relevant in “normal” times, as the values are consistent with investors’ orientation towards earnings as the ultimate source of returns (either dividends or capital appreciation). However, in more distressed times when earnings are depressed, indications of value using book value assume more relevance. If a bank has completed a recent acquisition or is in the midst of a strategic overhaul, then the discounted cash flow method may deserve greater emphasis. We prefer to assign quantitative weights to each indication of value, which provide transparency into the process by which value is determined.

Relative Value Analysis

The analysis is not complete, however, when a correlated value is obtained. It is crucial to compare the valuation multiples implied by the concluded value, such as the effective price/earnings and price/tangible book value multiples, against those reported by publicly traded banks. Any divergences should be explainable. For example, if the bank operates in a market with constrained growth prospects, then a lower than average price/earnings multiple may be appropriate. A higher return on equity for a subject bank, relative to the comparable companies, often results in a higher price/tangible book value multiple. As another reference point, the effective pricing multiples may be benchmarked against bank merger and acquisition pricing to ensure that an appropriate relationship exists between the subject minority interest value and a possible merger value.

Conclusion

There are many valuation issues that remain untouched by this article in the interest of brevity, such as the valuation treatment of S corporations and the discount for lack of marketability applicable to minority interests in banks with no active trading market. Instead, this article addresses issues commonly faced in valuing minority interests in any community bank. A well-reasoned valuation of a community bank requires understanding the valuation conventions applicable to banks, such as pricing multiples commonly employed or the appropriate source of cash flow in a DCF analysis, but within a risk and growth framework that underlies the valuation of all equity instruments. Relating these valuation parameters to a comprehensive analysis of a bank’s financial performance, risk factors, and strategic outlook results in a rigorous and convincing determination of value. In the next edition, we will move beyond the valuation of minority interests in banks, focusing on specific valuation nuances that arise when engaging in a valuation for merger purposes.

Originally published in Bank Watch, November 2019.

Kress v. U.S.

Scott A. Womack, ASA, MAFF, Senior Vice President, originally presented the session “Will Kress v. U.S. Change Your Life? Or Will It Change Your Valuation Practice?” at the Forensic and Valuation Services Conference hosted by the Tennessee Society of CPAs on October 23, 2019.

Should Kress be immediately considered as support for tax-affecting earnings of a pass-through entity? In this session, Scott Womack tackles that question by taking a deep dive into the case including viewpoints from the participating experts, presenting the views of other commentators, and discussing the appeal by the IRS and its withdrawal.

Key learning objectives include:

- Understand the key issues of Kress and their importance to your practice

- Review of arguments regarding tax-affecting vs. not tax-affecting

- Have knowledge of the range of opinions re Kress

- Understand how Kress impacts valuation of pass-through entities

Critical Issues in Valuation & Family Transitions | Auto Dealers

Scott A. Womack, ASA, MAFF, Senior Vice President, originally presented the session “Critical Issues in Business Valuations and Family Transitions for Auto Dealers” at the 2019 Lane Gorman Trubitt Controllers’ Roundtable on October 17, 2019.

Auto dealers, like most business owners, can actually influence the value of their store. What are some of the value drivers of a store valuation and areas that appraisers adjust for in business valuations? Mr. Womack presents on these topics and discusses key elements of buy-sell agreements and other family transition issues that he observes from his auto dealer practice.

2019 Core Deposit Intangibles Update

In our annual update of core deposit trends published a year ago, we described an increasing trend in core deposit intangible asset values in light of rising interest rates. At the time several more short-term rate hikes by the Fed were expected during 2018 and 2019. However, the equity and high yield credit markets disagreed as both fell sharply during the fourth quarter in anticipation of the December rate hike that the Fed later implemented.

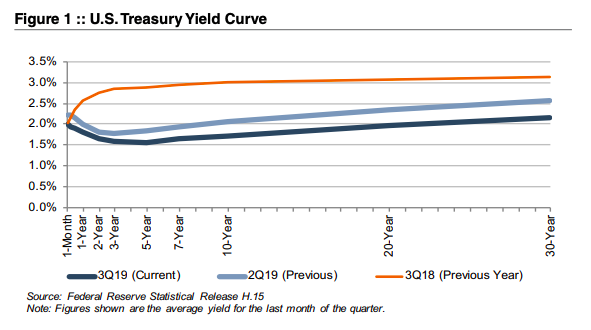

A year later the Fed has cut three times in 2019 and thereby erased three of the four hikes it implemented in 2018. As 2019 unfolded, intermediate- and long-term U.S. Treasury rates declined from what appears to be cycle highs reached in November 2018 through August 2019. As a result, the U.S. Treasury curve inverted with short-rates that are closely tied to the Fed’s policy rates exceeding intermediate- and long-term rates. By late August 3-month bills yielded about 50bps more than the 10-year bond. Also, the spread between 10-year and 2-year Treasuries, commonly cited as an indicator of impending recessions when negative, was nominally negative. During October intermediate- and long-term rates rose modestly in anticipation of the third Fed rate cut supporting economic growth and thereby flattened the curve.

Alongside these fluctuations in the interest rate environment, the banking industry has seen increasing competition for deposits in recent years. Improved loan demand in the post-recession period has led to greater funding needs, while competition from traditional banking channels has been compounded by the increased prevalence of online deposit products, often offering higher rates. All of these trends have combined to make strong core deposit bases increasingly valuable in bank acquisitions in the post-recession years. One question to ponder, however, is how much the value attributable to core deposits may ease given the reduction in rates that has occurred recently.

Using data compiled by S&P Global Market Intelligence, we analyzed trends in core deposit intangible (CDI) assets recorded in whole bank acquisitions completed from 2000 through September 2019. CDI values represent the value of the depository customer relationships obtained in a bank acquisition. CDI values are driven by many factors, including the “stickiness” of a customer base, the types of deposit accounts assumed, and the cost of the acquired deposit base compared to alternative sources of funding.

For our analysis of industry trends in CDI values, we relied on S&P Global Market Intelligence’s definition of core deposits.1 In analyzing core deposit intangible assets for individual acquisitions, however, a more detailed analysis of the deposit base would consider the relative stability of various account types. In general, CDI assets derive most of their value from lower-cost demand deposit accounts, while often significantly less (if not zero) value is ascribed to more rate-sensitive time deposits and public funds, or to non-retail funding sources such as listing service or brokered deposits which are excluded from core deposits when determining the value of a CDI.

Trends in CDI Values

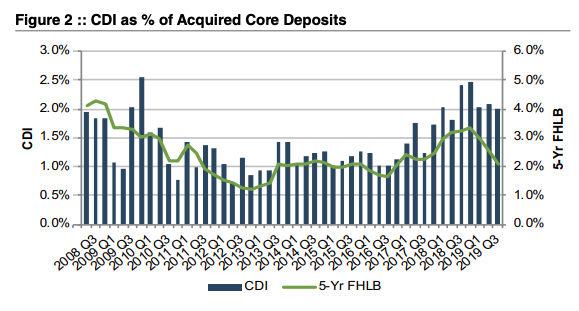

Figure 2 summarizes the trend in CDI values since the start of the 2008 recession, compared with rates on 5-year FHLB advances. Over the post-recession period, CDI values have largely followed the general trend in interest rates. As alternative funding became more costly during 2017 and 2018, CDI values generally ticked up as well, relative to post-recession average levels. During 2019, the trend reversed as CDI values have exhibited a declining trend in light of yield curve inversion and Fed rate cuts at its last three meetings.

This decline in CDI values has been somewhat slower than the drop in benchmark interest rates, however, in part because deposit costs typically lag broader movements in market interest rates. In general, banks were slow to raise deposit rates in the period of contractionary monetary policy through 2018 and, as a result, rates remain below benchmark levels leaving banks less room to reduce rates further. For CDs, the lagging trend is even more pronounced given their nature as time deposits. Many banks attempted to “lock-in” rates by increasing reliance on CDs when expectations were for continued rate increases as late as year-end 2018. Now that rates are on the decline, banks have been stuck with CDs that cannot be repriced until their maturities even as benchmark rates fall. While time deposits typically are not considered “core deposits” in an acquisition and thus would not directly influence CDI values, they do significantly influence a bank’s overall cost of funds, and while funding costs remain high a strong core deposit base remains a valuable asset to acquirers.

Even as CDI assets remain above post-recession average levels at approximately 2.0- 2.5%, they are still below long-term historical levels which averaged closer to 2.5-3.0% in the early 2000s.

Accounting for CDI Assets

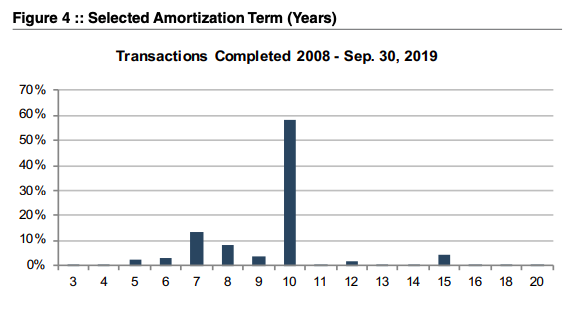

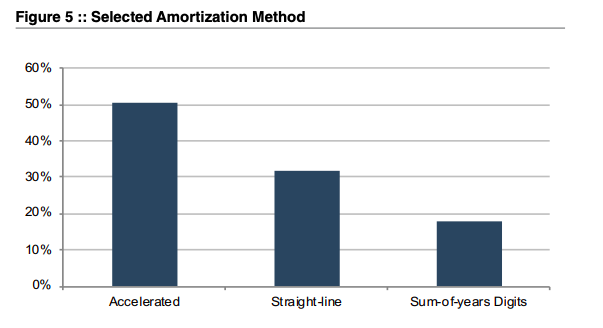

Based on the data for acquisitions for which core deposit intangible detail was reported, a majority of banks selected a ten-year amortization term for the CDI values booked. Less than 10% of transactions for which data was available selected amortization terms longer than ten years. Amortization methods were somewhat more varied, but an accelerated amortization method was selected in more than half of these transactions.

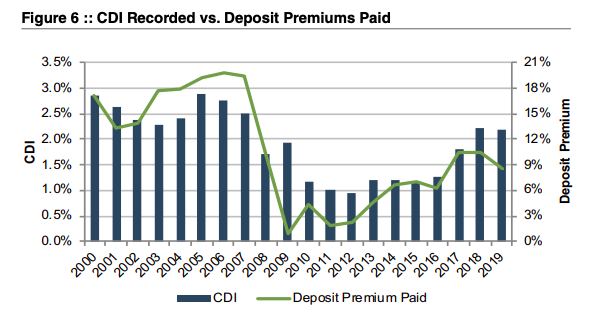

Trends in Deposit Premiums Relative to CDI Asset Values

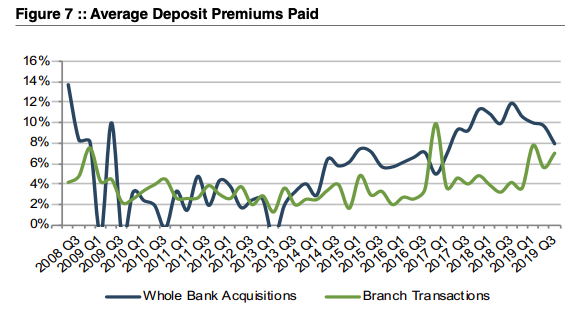

Core deposit intangible assets are related to, but not identical to, deposit premiums paid in acquisitions. While CDI assets are an intangible asset recorded in acquisitions to capture the value of the customer relationships the deposits represent, deposit premiums paid are a function of the purchase price of an acquisition. Deposit premiums in whole bank acquisitions are computed based on the excess of the purchase price over the target’s tangible book value, as a percentage of the core deposit base. While deposit premiums often capture the value to the acquirer of assuming the established funding source of the core deposit base (that is, the value of the deposit franchise), the purchase price also reflects factors unrelated to the deposit base, such as asset quality in the acquired loan base, unique synergy opportunities anticipated by the acquirer, etc. Any additional factors may influence the purchase price to an extent that the calculated deposit premium doesn’t necessarily bear a strong relationship to the value of the core deposit base to the acquirer. This influence is often less relevant in branch transactions where the deposit base is the primary driver of the transaction and the relationship between the purchase and the deposit base is more direct.

Deposit premiums paid in whole bank acquisitions have shown more volatility than CDI values. Despite improved deal values in recent years, current deposit premiums in the high single digits remain well below the pre-financial crisis levels when premiums for whole bank acquisitions averaged closer to 20%.

Deposit premiums paid in branch transactions have generally been less volatile than tangible book value premiums paid in whole bank acquisitions. Branch transaction deposit premiums have averaged in the 5.5%-7.5% range during 2019, up from the 2.0-4.0% range observed in the financial crisis, and have continued to rise in recent quarters in light of increasing deposit competition.

For more information about Mercer Capital’s core deposit valuation services, please contact us.

Originally published in Bank Watch, October 2019.

Valuation Issues in Auto Dealer Litigation

In our family law and commercial litigation practice, we often serve as expert witnesses in auto dealership valuation disputes. We hope you never find yourself a party to a legal dispute; however, we offer the following words of wisdom based upon our experience working in these valuation-related disputes. The following topics, posed as questions, have been points of contention or common issues that have arisen in recent disputes. We present them here so that if you are ever party to a dispute, you will be a more informed user of valuation and expert witness services.

Should Your Expert Witness be a Valuation or Industry Expert?

Oftentimes, the financial and business valuation portion of a litigation is referred to as a “battle of the experts” because you have at least two valuation experts, one for the plaintiff and one for the defendant. In the auto dealer world, you are hopefully combining valuation expertise with a highly-specialized industry. It is critical to engage an expert who is both a valuation expert and an industry expert – one who holds valuation credentials and has deep valuation knowledge and also understands and employs accepted industry-specific valuation techniques. Look with caution upon valuation experts with minimal industry experience who utilize general valuation methodologies often reserved for other industries (for example, Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) or multiples of Earnings Before Interest, Taxes and Depreciation (EBITDA)) with no discussion of Blue Sky multiples.

Does the Appraisal Discuss Local Economic Conditions and Competition Adequately?

The auto industry, like most industries, is dependent on the climate of the national economy. Additionally, auto dealers can be dependent or affected by conditions that are unique to their local economy. The type of franchise relative to the local demographics can also have a direct impact on the success/profitability of a particular auto dealer. For example, a luxury or high-line franchise in a smaller or poorer market would not be expected to fare as well as one in a market that has a larger and wealthier demographic.

In those areas that are dependent on a local economy/industry, an understanding of that economy/industry becomes just as important as an understanding of the overall auto dealer industry and national economy. Common examples are local markets that are home to a military base, oil & gas markets in Western Texas or natural gas in Pennsylvania, or fishing industries in coastal areas. There’s also a fine balance between understanding and acknowledging the impact of that local economy without overstating it. Often some of the risks of the local economy are already reflected in the historical operating results of the dealership.

If There Are Governing Corporate Documents, What Do They Say About Value, and Should They Be Relied Upon?

Many of the corporate entities involved in litigation have sophisticated governance documents that include Operating Agreements, Buy-Sell Agreements, and the like. These documents often contain provisions to value the stock or entity through the use of a formula or process. Whether or not these agreements are to be relied upon in whole or in part in a litigated matter is not always clear. In litigated matters, focus will be placed on whether the value concluded from a governance document represents fair market value, fair value, or some other standard of value. However, the formulas contained in these agreements are not always specific to the industry and may not include accepted valuation methodology for auto dealers.

Two common questions that arise concerning these agreements are 1) has an indication of value ever been concluded using the governance document in the dealership’s history (in other words, has the dealership been valued using the methodology set out in the document)?; and 2) have there been any transactions, buy-ins or redemptions utilizing the values concluded in a governance document? These are important questions to consider when determining the appropriate weight to place on a value indication from a governance document.

Some litigation matters (such as divorce) state that the non-business party to the litigation is not bound by the value indicated by the governance document since they were not a signed party to that particular agreement. It is always important to discuss this issue with your attorney.

Have There Been Prior Internal Transactions of Company Stock and at What Price?

Similar to governance documents, another possible data point(s) in valuing an auto dealership are internal transactions. A good appraiser will always ask if there have been prior transactions of company stock and, if so, how many have occurred, when did they occur, and at what terms did they occur? There is no magic number, but as with most statistics, more transactions closer to the date of valuation can often be considered as better indicators of value than fewer transactions further from the date of valuation.

An important consideration in internal transactions is the motivation of the buyer and seller. If there have been multiple internal transactions, appraisers have to determine the appropriateness of which transactions to possibly include and which to possibly exclude in their determination of value. Without an understanding of the motivation of the parties and of the specific facts of the transactions, it becomes trickier to include some, but exclude others. The more logical conclusion would be to include all of the transactions or exclude all of the transactions with a stated explanation.

What Do the Owner’s Personal Financial Statements Say and Are They Important?

Most owners of an auto dealership have to submit personal financial statements as part of the guarantee on the floor plan and other financing. The personal financial statement includes a listing of all of the dealer’s assets and liabilities, typically including some value assigned to the value of the dealership. In litigated matters, these documents are important as another data point to valuation.

One view of the value placed on a dealership in an owner’s personal financial statement is that no formal valuation process was used to determine that number; so, at best, it’s a thumb in the air, blind estimate of value. The opposing view is the individual submitting the personal financial statement is attesting to the accuracy and reliability of the financial figures contained in document under penalty of perjury. Further, some would say that the value assigned to the dealership has merit because the business owner is the most informed person regarding the business, its future growth opportunities, competition, and the impact of economic and industry factors on the business.

For an appraiser, it’s not a good situation to be surprised by the existence of these documents. A good business appraiser will always ask for them. The dealership value indicated in a personal financial statement should be viewed in light of value indications under other methodologies and sources of information. At a minimum, personal financial statements may require the expert to ask more questions or use other factors, such as the national and local economy, to explain any difference in values over time.

Does the Appraiser Understand the Industry and How to Use Comparable Industry Profitability Data?

The auto dealer industry is highly specialized and unique and should not be compared to general retail or manufacturing industries. As such, any sole comparison to general industry profitability data should be avoided.

If your appraiser solely uses the Annual Statement Studies provided by the Risk Management Association (RMA) as a source of comparison for the balance sheet and income statement of your dealership to the industry, this is problematic. RMA’s studies are organized by the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). Typical new and used retail auto dealers would fall under NAICS #441110 or #441120. This general data does not distinguish between different franchises.

Is there better or more specialized data available? Yes, the National Automobile Dealers Association (NADA) publishes monthly Dealership Financial Profiles broken down by Average Dealerships, which would be comparable to RMA data. However, NADA drills down further, segmenting the industry into the four following categories: Domestic Dealerships, Import Dealerships, Luxury Dealerships and Mass Market Dealerships. While no single comparison is perfect, an appraiser should know to consult more specific industry profitability data when available.

Do You Understand Actual Profitability vs. Expected Profitability and Why It’s Important?

Either through an income or Blue Sky approach, auto dealers are typically valued based upon expected profitability rather than the actual profitability of the business.

The difference between actual and expected profitability generally consists of normalization adjustments. Normalization adjustments are adjustments made for any unusual or non-recurring items that do not reflect normal business operations. During the due diligence interview with management, an appraiser should ask does the dealership have non-recurring or discretionary expenses and are personal expenses of the owner being paid by the business? Comparing the dealership to industry profitability data as discussed earlier can help the appraiser understand the degree to which the dealership may be underperforming.

An example of how normalizing adjustments work is helpful. If a dealership has historically reported 2% earnings before taxes (EBT) and the NADA data suggests 5%, the financial expert must analyze why there is a difference between these two data points and determine if there are normalizing adjustments to be applied. Let’s use some numbers to illustrate this point. For a dealership with revenue of $25 million, historical profitability at 2% would suggest EBT of $500,000. At 5%, expected EBT would be $1,250,000, or an increase of $750,000. In this case, the financial expert should analyze the financial statements and the dealership to determine if normalization adjustments are appropriate which, when made, will reflect a more realistic figure of the expected profitability of the dealership without non-recurring or personal owner expenses. This is important because, hypothetically, a new owner could optimize the business and eliminate some of these expenses; therefore, even dealerships with a history of negative or lower earnings can receive higher Blue Sky multiples because a buyer believes they can improve the performance of the dealership. However, as noted earlier, the dealership may be affected by the local economy and other issues that cannot be fixed so the lower historical EBT may be justified.

For more information on normalizing adjustments, see our article Automobile Dealership Valuation 101.

Conclusion

The valuation of automobile dealerships can be complex. A deep understanding of the industry along with valuation expertise is the optimal combination for general valuation needs and certainly for valuation-related disputes. If you have a valuation issue, feel free to contact us to discuss it in confidence.

Originally published in the Value Focus: Auto Dealer Industry Newsletter, Mid-Year 2019.

Five Trends to Watch in the Medical Device Industry

The medical device manufacturing industry produces equipment designed to diagnose and treat patients within global healthcare systems. Medical devices range from simple tongue depressors and bandages, to complex programmable pacemakers and sophisticated imaging systems. Major product categories include surgical implants and instruments, medical supplies, electro-medical equipment, in-vitro diagnostic equipment and reagents, irradiation apparatuses, and dental goods.

The following outlines five structural factors and trends that influence demand and supply of medical devices and related procedures.

1. Demographics

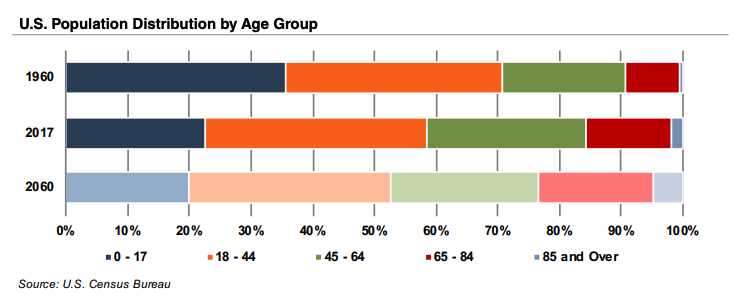

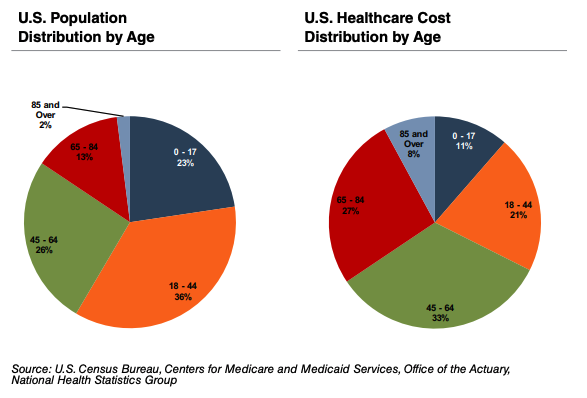

The aging population, driven by declining fertility rates and increasing life expectancy, represents a major demand driver for medical devices. The U.S. elderly population (persons aged 65 and above) totaled 49 million in 2016 (15% of the population). The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that the elderly will roughly double by 2060 to 95 million, representing 23% of the total population.

The elderly account for nearly one third of total healthcare consumption. Personal healthcare spending for the population segment was $19,000 per person in 2014, five times the spending per child ($3,700) and almost triple the spending per working-age person ($7,200).

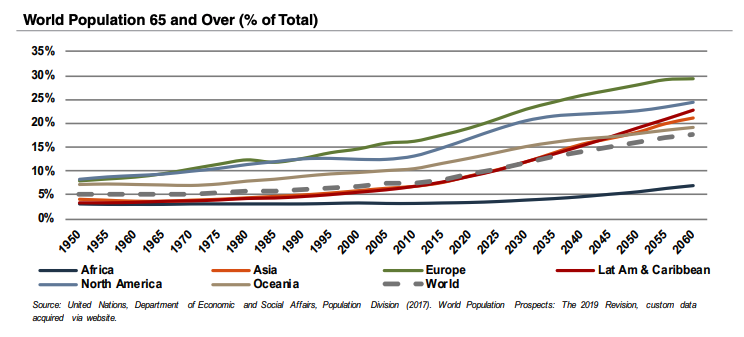

According to United Nations projections, the global elderly population will rise from approximately 607 million (8.2% of world population) in 2015 to 1.8 billion (17.8% of world population) in 2060. Europe’s elderly are projected to reach approximately 29% of the population by 2060, making it the world’s oldest region. While Latin America and Asia are currently relatively young, these regions are expected to undergo drastic transformations over the next several decades, with the elderly population expected to expand from less than 8% in 2015 to more than 21% of the total population by 2060.

2. Healthcare Spending and the Legislative Landscape in the U.S.

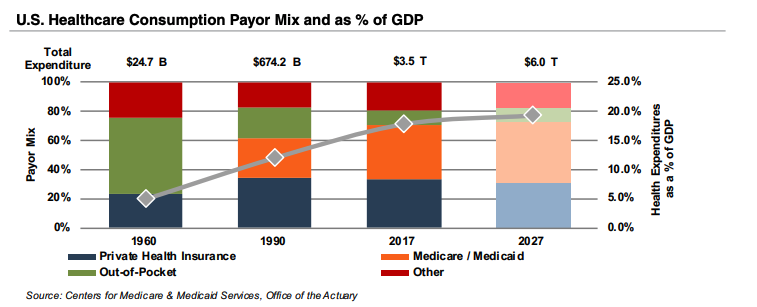

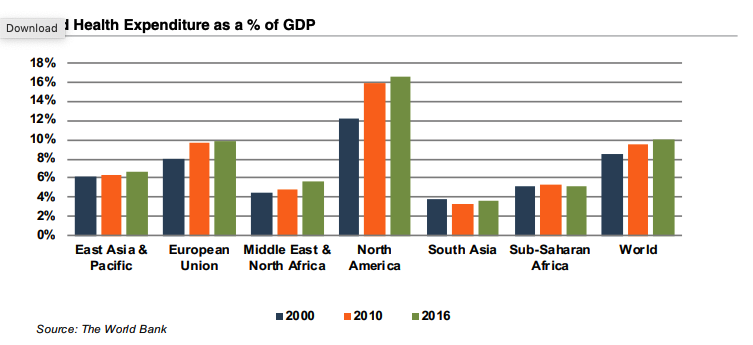

Demographic shifts underlie the expected growth in total U.S. healthcare expenditure from $3.5 trillion in 2017 to $6.0 trillion in 2027, an average annual growth rate of 5.5%. While this projected average annual growth rate is more modest than that of 7.0% observed from 1990 through 2007, it is more rapid than the observed rate of 4.3% between 2008 and 2017. Projected growth in annual spending for Medicare (7.9%) is expected to contribute substantially to the increase in national health expenditure over the coming decade. Healthcare spending as a percentage of GDP is expected to expand from 17.9% in 2017 to 19.4% by 2027.

Since inception, Medicare has accounted for an increasing proportion of total U.S. healthcare expenditures. Medicare currently provides healthcare benefits for an estimated 60 million elderly and disabled people, constituting approximately 15% of the federal budget in 2018. Medicare represents the largest portion of total healthcare costs, constituting 20% of total health spending in 2017. Medicare also accounts for 25% of hospital spending, 30% of retail prescription drugs sales, and 23% of physician services.

Owing to the growing influence of Medicare in aggregate healthcare consumption, legislative developments can have a potentially outsized effect on the demand and pricing for medical products and services. Net mandatory benefit outlays (gross outlays less offsetting receipts) to Medicare totaled $591 billion in 2017, and are expected to reach $1.3 trillion by 2028.

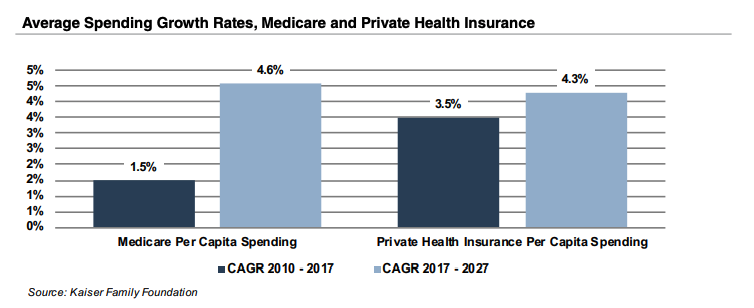

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“ACA”) of 2010 incorporated changes that are expected to constrain annual growth in Medicare spending over the next several decades, including reductions in Medicare payments to plans and providers, increased revenues, and new delivery system reforms that aim to improve efficiency and quality of patient care and reduce costs. On a per person basis, Medicare spending is projected to grow at 4.6% annually between 2017 and 2027, compared to 1.5% average annualized growth realized between 2010 and 2017, and 7.3% during the 2000s.

As part of ACA legislation, a 2.3% excise tax was imposed on certain medical devices for sales by manufacturers, producers, or importers. The tax had become effective on December 31, 2012, but met resistance from industry participants and policy makers. In late 2015, Congress passed legislation promulgating a two-year moratorium on the tax beginning January 2016. In January 2018, the moratorium suspending the medical device excise tax was extended through 2019.

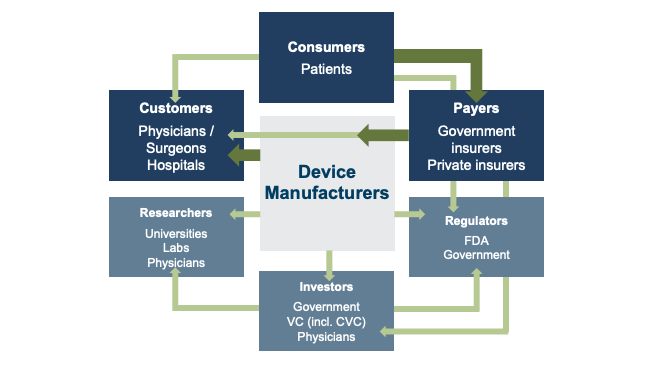

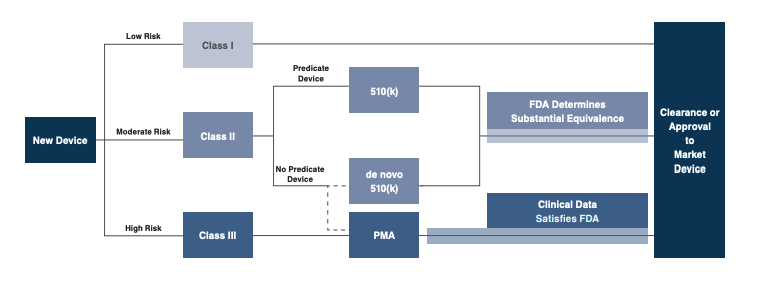

3. Third-Party Coverage and Reimbursement

The primary customers of medical device companies are physicians (and/or product approval committees at their hospitals), who select the appropriate equipment for consumers (patients). In most developed economies, the consumers themselves are one (or more) step removed from interactions with manufacturers, and therefore pricing of medical devices. Device manufacturers ultimately receive payments from insurers, who usually reimburse healthcare providers for routine procedures (rather than for specific components like the devices used). Accordingly, medical device purchasing decisions tend to be largely disconnected from price.