8 Things to Know About Section 409A

1. What is Section 409A?

Section 409A is a provision of the Internal Revenue Code that applies to all companies offering nonqualified deferred compensation plans to employees. Generally speaking, a deferred compensation plan is an arrangement whereby an employee (“service provider” in 409A parlance) receives compensation in a later tax year than that in which the compensation was earned. “Nonqualified” plans exclude 401(k) and other “qualified” plans.

What is interesting from a valuation perspective is that stock options and stock appreciation rights (SARs), two common forms of incentive compensation for private companies, are potentially within the scope of Section 409A. The IRS is concerned that stock options and SARs issued “in the money” are really just a form of deferred compensation, representing a shifting of current compensation to a future taxable year. So, in order to avoid being subject to 409A, employers (“service recipients”) need to demonstrate that all stock options and SARs are issued “at the money” (i.e., with the strike price equal to the fair market value of the underlying shares at the grant date). Stock options and SARs issued “out of the money” do not raise any particular problems with regard to Section 409A.

2. What are the consequences of Section 409A?

Stock options and SARs that fall under Section 409A create problems for both service recipients and service providers. Service recipients are responsible for normal withholding and reporting obligations with respect to amounts includible in the service provider’s gross income under Section 409A. Amounts includible in the service provider’s gross income are also subject to interest on prior underpayments and an additional income tax equal to 20% of the compensation required to be included in gross income. For the holder of a stock option, this can be particularly onerous as, absent exercise of the option and sale of the underlying stock, there has been no cash received with which to pay the taxes and interest.

These consequences make it critical that stock options and SARs qualify for the exemption under 409A available when the fair market value of the underlying stock does not exceed the strike price of the stock option or SAR at the grant date.

3. What constitutes “reasonable application of a reasonable valuation method”?

For public companies, it is easy to determine the fair market value of the underlying stock on the grant date. For private companies, fair market value cannot be simply looked up on Bloomberg. Accordingly, for such companies, the IRS regulations provide that “fair market value may be determined through the reasonable application of a reasonable valuation method.” In an attempt to clarify this clarification, the regulations proceed to state that if a method is applied reasonably and consistently, such valuations will be presumed to represent fair market value, unless shown to be grossly unreasonable. Consistency in application is assessed by reference to the valuation methods used to determine fair market value for other forms of equity-based compensation. An independent appraisal will be presumed reasonable if “the appraisal satisfies the requirements of the Code with respect to the valuation of stock held in an employee stock ownership plan.”

A reasonable valuation method is to consider the following factors:

The value of tangible and intangible assets

The present value of future cash flows

The market value of comparable businesses (both public and private)

Other relevant factors such as control premiums or discounts for lack of marketability

Whether the valuation method is used consistently for other corporate purposes

In other words, a reasonable valuation considers the cost, income, and market approaches, and considers the specific control and liquidity characteristics of the subject interest. For start-up companies, the valuation would also consider the company’s most recent financing round and the rights and preferences of any securities issued. The IRS is also concerned that the valuation of common stock for purposes of Section 409A be consistent with valuations performed for other purposes.

4. How is fair market value defined?

Fair market value is not specifically defined in Section 409A of the Code or the associated regulations. Accordingly, we look to IRS Revenue Ruling 59-60, which defines fair market value as “the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller when the former is not under any compulsion to buy and the latter is not under any compulsion to sell, both parties having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.”

5. Does fair market value incorporate a discount for lack of marketability?

Among the general valuation factors to be considered under a reasonable valuation method are “control premiums or discounts for lack of marketability.” In other words, if the underlying stock is illiquid, the stock should presumably be valued on a non-marketable minority interest basis.

This is not without potential confusion, however. In an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP), stock issued to participants is generally covered by a put right with respect to either the Company or the ESOP. Accordingly, valuation specialists often apply marketability discounts on the order of 0% to 10% to ESOP shares. Shares issued pursuant to a stock option plan may not have similar put rights attached, and therefore may warrant a larger marketability discount. In such cases, a company that has an annual ESOP appraisal may not have an appropriate indication of fair market value for purposes of Section 409A.

6. Are formula prices reliable measures of fair market value?

In addition to independent appraisals, formula prices may, under certain circumstances, be presumed to represent fair market value. Specifically, the formula cannot be unique to the subject stock option or SAR, but must be used for all transactions in which the issuing company buys or sells stock.

7. What are the rules for start-ups?

For purposes of Section 409A compliance, start-ups are defined as companies that have been in business for less than ten years, do not have publicly traded equity securities, and for which no change of control event or public offering is reasonably anticipated to occur in the next twelve months. For start-up companies, a valuation will be presumed reasonable if “made reasonably and in good faith and evidenced by a written report that takes into account the relevant factors prescribed for valuations generally under these regulations.” Further, such a valuation must be performed by someone with “significant knowledge and experience or training in performing similar valuations.”

This presumption, while presented as a separate alternative, strikes us a substantively and practically similar to the independent appraisal presumption described previously. Some commentators have suggested that the valuation of a start-up company may be performed by an employee or board member of the issuing company. We suspect that it is the rare employee or board member that is actually qualified to render the described valuation.

The bottom line is that Section 409A applies to both start-ups and mature companies.

8. Who is qualified to determine fair market value?

The safe harbor presumptions of Section 409A apply only when the valuation is based upon an independent appraisal, and it is likely that a valuation prepared by an employee or board member would raise questions of independence and objectivity.

The regulations also clarify that the experience of the individual performing the valuation generally means at least five years of relevant experience in business valuation or appraisal, financial accounting, investment banking, private equity, secured lending, or other comparable experience in the line of business or industry in which the service recipient operates.

In our reading of the rules, this means that the appraisal should be prepared by an individual or firm that has a thorough educational background in finance and valuation, has accrued significant professional experience preparing independent appraisals, and has received formal recognition of his or her expertise in the form of one or more professional credentials (ASA, ABV, CBA, or CFA). The valuation professionals at Mercer Capital have the depth of knowledge and breadth of experience necessary to help you navigate the potentially perilous path of Section 409A.

Originally published in the Financial Reporting Update: Equity Compensation, June 2019.

Shelf Life of an Equity Compensation Valuation

Clients frequently want to know, “How long is an equity compensation valuation good for?” We get it. You want to provide employees, contractors, and other service providers who are compensated through company stock with current information about their interests, but the time and cost required to get a valuation must also be considered.

Due to the natural business changes every company goes through, accounting and legal professionals often recommend updates at least annually if no significant change or financing has occurred. However, unique company or market characteristics often necessitate more frequent updates. Here are some of the factors to consider when determining the need for a valuation update:

- Significant changes in the company’s financial situation

- Shift in overall strategy

- Achievement of business milestones

- Changes in market or industry conditions

- Gain or loss of major customer accounts

- Additional funding

- Issuance of new equity compensation

- Potential for an upcoming IPO

- Changes in expectation as to the timing of an exit event

Even for companies that have fairly steady operations, the effects of small business changes accumulate over time. Companies that deal with major changes relatively infrequently may be suited to regular summary updates to supplement full comprehensive reports as a way to maximize the cost-benefit analysis of equity compensation valuation.

Originally published in the Financial Reporting Update: Equity Compensation, June 2019.

Simple vs. Complex Capital Structures

Executives expend a great deal of effort to determine the optimal way to finance the operations of their businesses. This may involve bringing on outside investors, employing bank debt, or financing through cash flow. Once the money has hit the bank, they may wonder, what effect does the capitalization of my company have on the value of its equity?

A company with a simple capital structure typically has been financed through the issuance of one class of stock (usually common stock). Companies with complex capital structures, on the other hand, may include other instruments: multiple classes of stock, forms of convertible debt, options, and warrants. This is frequent in startup or venture-backed companies that receive financing through multiple channels or fundraising rounds and private equity sources.

With various types of stock on the cap table, it is important to note that all stock classes are not the same. Each class holds certain rights, preferences, and priorities of return that can confer a portion of enterprise value to the shares besides their pro rata allocation. These often come in two categories: economic rights and control rights. Economic rights bestow financial benefits while control rights grant benefits related to operations and decision making.

Economic rights:

- Liquidation preference

- Dividends

- Mandatory redemption rights

- Conversion rights

- Participation rights

- Anti-dilution rights

- Registration rights

Control rights:

- Voting rights

- Protective provisions

- Veto rights

- Board composition rights

- Drag-along rights

- Right to participate in future rounds (pro-rata rights)

- First refusal rights

- Tag-along rights

- Management rights

- Information rights

The value of a certain class of stock is affected both by the rights and preferences it holds as well as those held by the other share classes on the cap table. The presence of multiple preferred classes also brings up the issue of seniority as certain class privileges may be overruled by those of a more senior share class.

Complex capital structures require complex valuation models that can integrate and prioritize the special treatments of individual share classes in multi-class cap tables. As such, models such as the PWERM or OPM are better-suited for these types of circumstances.

Originally published in the Financial Reporting Update: Equity Compensation, June 2019.

Calibrating or Reconciling Valuation Models to Transactions in a Company’s Equity

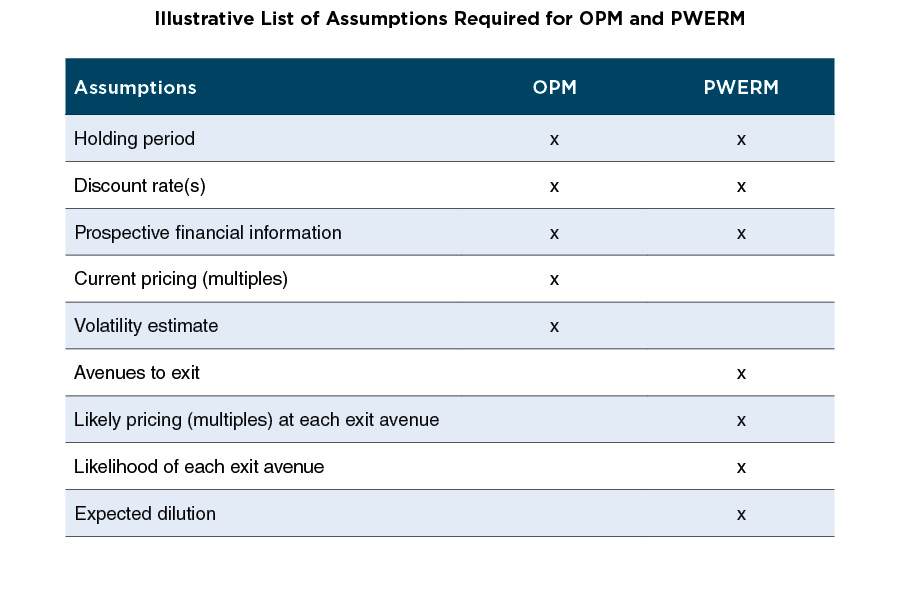

When an exit event is not imminent, the appropriate models to measure the fair value of a company with a complex capital stack are the Probability Weighted Expected Return Method (PWERM), the Option Pricing Method (OPM), or some combination of the two. While the choice of the model(s) is often dictated by facts and circumstances – for example, the company’s stage of development, visibility into exit avenues, etc. – using either the PWERM or the OPM requires a number of key assumptions that may be difficult to source or support for pre-public, often pre-profitable, companies. In this context, primary or secondary transactions involving the company’s equity instruments, which may or may not be identical to common shares, can be useful in measuring fair value or evaluating overall reasonableness of valuation conclusions.

For companies granting equity-based compensation, transactions are likely to take the form of either issuances of preferred shares as part of fundraising rounds or secondary transactions of equity instruments (preferred or common shares, as part of a fundraising round or on a standalone basis). Fundraising rounds usually do not provide pricing indications for common shares (or options on common) directly. However, a backsolve exercise that calibrates the PWERM and/or the OPM to the price of the new-issue preferred shares can provide value indications for the entire enterprise and common shares. While standalone secondary transactions may involve common shares, facts and circumstances around those transactions may determine the usefulness of related pricing information for any calibration or reconciliation exercise. Calibration, when viable, provides not only comfort around the overall soundness of valuation models and assumptions, but also a platform on which future value measurements can be based.

This article presents a brief discussion on evaluating observed or prospective transactions. Not all transactions are created equal – a fair value analysis should consider the facts and circumstances around the transactions to assess whether (and the degree to which) they are useful and relevant, or not.1

Fair Value

ASC 718 Compensation-Stock Compensation defines fair value as “the amount at which an asset (or liability) could be bought (or incurred) or sold (or settled) in a current transaction between willing parties, that is, other than in a forced or liquidation sale.” ASC 820 Fair Value Measurement defines fair value as “the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.” While some of the finer nuances may differ slightly, both definitions make reference to the concepts of i) willing and informed buyers and sellers, and ii) orderly transactions.

Notably, ASC 820 includes the directive that “valuation techniques used to measure fair value shall maximize the use of relevant observable inputsÉand minimize the use of unobservable inputs.” We take this to mean that pricing information from transactions should be used in the measurement (valuation) process as long as they are relevant from a fair value perspective.

Willing and Informed Parties

A fundraising round involving new investors, assuming the company is not in financial distress, tends to involve negotiations between sophisticated buyers (investors) and informed sellers (issuing companies). As such, these transactions are relevant in measuring the fair value of equity instruments, including those granted as compensation.

When a fundraising round does not involve new investors, the parties to the transaction are not necessarily independent of each other. However, such a round may still be relevant from a fair value perspective if pricing resulted from robust negotiations or was otherwise reflective of market pricing.

Secondary Transactions – Orderly Transactions?

As they give rise to observable inputs, secondary transactions can be relevant in the measurement process if the pricing information is reflective of fair value. Pricing from transactions in an active market for an identical equity instrument would generally reflect fair value. In other cases, orderly transactions Ð those that have received adequate exposure to the appropriate market, allowed sufficient marketing activities, and were not forced or distressed Ð can give rise to transaction prices that are reconcilable with fair value. Orderly secondary transactions that are relatively larger and those that involve equity instruments similar to the subject interests are more relevant.

Strategic Elements

Some fundraising rounds involve strategic investors who may receive economic benefits beyond just the ownership interest in the company. The strategic benefits could be codified in explicit contracts like a licensing arrangement. Consideration paid for equity interests acquired in such transactions may exceed the price a market participant (with no strategic interests) would consider reasonable. However, even as the pricing indication from such a transaction may not be directly relevant, it can be a useful reference or benchmark in measuring fair value. For example, it may be possible to estimate the excess economic benefits accruing to the strategic investors. Any fair value indication obtained separately could then be compared and reconciled to the price from the strategic fundraising rounds.

In other instances, strategic rounds may result in the company and investors sharing equally in the excess economic benefits. The transaction price could then be reflective of fair value, and a backsolve analysis to calibrate to the transaction price would be viable.

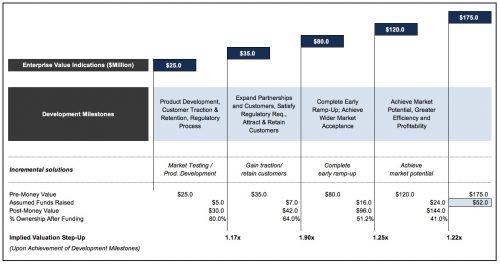

More Complex Structures

A tranched preferred investment may segment the purchase of equity interests into multiple installments. Pricing for such a round is usually set before the transaction and is identical across the installments, but future cash infusions may be contingent on specified milestones. Value of a company usually increases upon achieving technical, regulatory, or financial milestones. Even when future installments are not contingent on specified milestones, value may increase over time as the company makes progress on its business plan. Pricing set before the first installment tends to reflect a premium to the value of the company at the initial transaction date as it likely includes some expectation of potential economic upside from future installments. On the other hand, the same price may reflect a discount from the value of the company at future installment dates as the investments are (only) made once the economic upside is realized. Accordingly, a reconciliation to pricing information from these fundraising rounds may require separate estimates of the expectation of future upside (for the initial transaction date) and future values implied by the initial terms of the transaction (for later installment dates).

Some fundraising rounds involve purchases of a mix of equity instruments across the capital stack (i.e. different vintages of preferred and/or common) for the same or similar stated price per share. Usually, common shares involved in mixed purchases represent secondary transactions. From a fair value perspective, the transaction could be relevant in the aggregate and provide a basis to discern prices for each class of equity involved (considering the differences in rights and preferences among the classes). In other instances, either the company or the investor may have entered into a transaction for additional strategic benefits beyond just the economics reflected in the share prices. Depending on whether the buyer or the seller expects the additional strategic benefits, reported pricing may exceed the fair value of common shares or understate the value of the preferred shares. In yet other instances, mixed purchases at the same or similar prices may indicate a high likelihood of an initial public offering (IPO) in the near future. Typically, preferred shares convert into common at IPO and only one class of share exists subsequently.

Timing of Transactions and Other Events

Perhaps obviously, for both secondary and primary transactions, more proximate pricing indications are generally more directly useful for fair value measurement. Older, orderly transactions involving willing and informed parties would have been reflective of fair value at the time they occurred. If a more recent pricing observation is not available, current value indications could still be reconciled with the older transactions by considering changes at the company (and general market conditions) since the transaction date.

Planned future fundraising rounds could also provide useful information. In addition to the factors already addressed, a fair value analysis at the measurement date would need to consider the risk around the closing of the transaction.

Besides the usual transactions, other events that occur subsequent to the measurement date could still have a bearing on fair value. Future events that were known or knowable to market participants at the valuation date should be considered in measuring fair value. Events that were not known or knowable, but were still quite significant, may require separate disclosures.

Special Case – IPOs

An example of a special event on the horizon is an impending IPO. An IPO is usually a complex process that is executed over a relatively long period. At various points during the process, the company’s board or management, or the underwriter (investment banker) may project or estimate the IPO price. These estimates may change frequently or significantly until the actual IPO price is finalized. Even the actual IPO price may be subject to specific supply and demand conditions in the market at or near the date of final pricing. Subsequent trading often occurs at prices that vary (sometimes drastically) from the IPO price. For these reasons, estimates or actual IPO prices are unlikely to be reflective of fair value for pre-IPO companies.

Setting aside the uncertainties and idiosyncrasies around the process, an IPO provides ready liquidity for investors and access to public capital markets for the company. The act of going public ameliorates the risks associated with the lack of marketability of investments in a company. Easier access to public markets generally lowers the cost of capital, which would engender higher enterprise values. Accordingly, fair value of a minority equity interest prior to an IPO is generally perceived to be meaningfully different from (estimates of) the IPO price.

Conclusion

Incorporating information from observed or prospective transactions can help calibrate the PWERM or the OPM (or other valuation methods), along with the underlying assumptions. However, a valuation analysis should evaluate the transactions to assess whether they are relevant. Even when they are not directly relevant, transactions can help gauge the reasonableness of valuation conclusions.

Valuation specialists are fond of thinking their craft involves a blend of technique and judgment. The specific mechanics of models and methods, and related computations, represent the technical aspect. There is certainly some judgment involved in developing or selecting the assumptions that feed into the models. Judgment plays a bigger role, perhaps, in weaving together the models, assumptions, valuation conclusions, and other facts and circumstances, including transactions, into a coherent and compelling narrative.

Contact Mercer Capital with your valuation needs. We combine technical knowledge and judgment developed over decades of practice to serve our clients.

1 The discussion presented in this article is a summary of our reading of the relevant sections in the following:

Valuation of Privately-Held-Company Equity Securities Issued as Compensation, AICPA Accounting & Valuation Guide, 2013

Valuation of Portfolio Company Investments of Venture Capital and Private Equity Funds and Other Investment Companies, Working Draft of AICPA Accounting & Valuation Guide, 2018

Originally published in the Financial Reporting Update: Equity Compensation, June 2019.

Valuation Methods for Private Company Equity-Based Compensation

Equity-based compensation has been a key part of compensation plans for years. When the equity compensation involves a publicly traded company, the current value of the stock is known and so the valuation of share-based payments is relatively straightforward. However, for private companies, the valuation of the enterprise and associated share-based compensation can be quite complex.

The AICPA Accounting & Valuation Guide, Valuation of Privately-Held-Company Equity Securities Issued as Compensation, describes four criteria that should be considered when selecting a method for valuing equity securities:

- Going Concern. The method should align with the going-concern status of the company, including expectations about future events and the timing of cash flows. For example, if acquisition of the company is imminent, then expectations regarding the future of the enterprise as a going concern are not particularly relevant.

- Common Share Value. The method should assign some value to the common shares, unless the company is in liquidation with no expected distributions to common shareholders.

- Independent Replication. It is important that the results of the method used by a valuation specialist can be independently replicated or approximated using the same underlying data and assumptions. When completing the valuation, proprietary practices and models should not be the primary method of determining value.

- Complexity and Stage of Development. The complexity of the method selected should be appropriate to the company’s stage of development. In other words, a simpler valuation method (like an OPM) with fewer underlying assumptions may be more appropriate for an early-stage entity with few employees than a highly complex method (like a PWERM).

With these considerations in mind, let’s take a closer look at the four most common methods used to value private company equity securities.

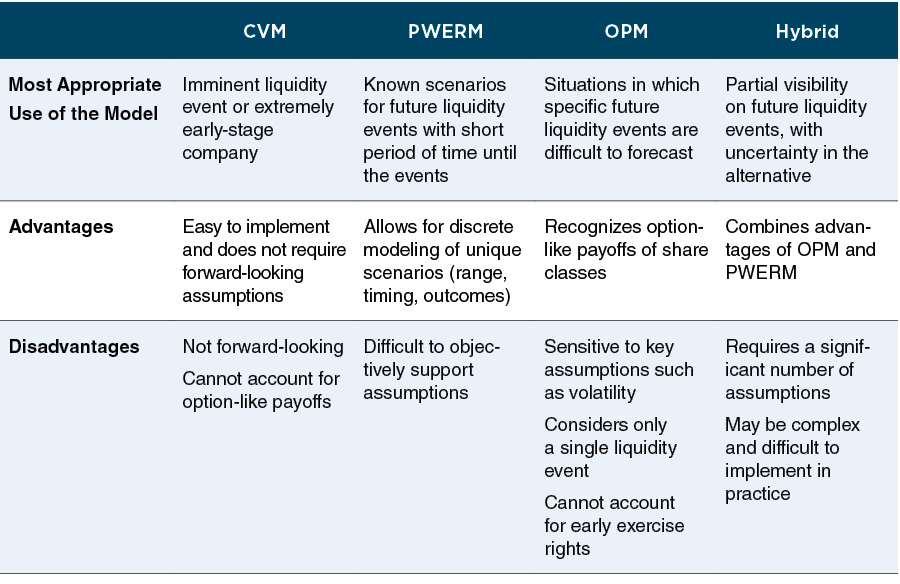

Current Value Method (CVM)

The Current Value Method estimates the total equity value of the company on a controlling basis (assuming an immediate sale) and subtracts the value of the preferred classes based on their liquidation preferences or conversion values. The residual is then allocated to common shareholders. Because the CVM is concerned only with the value of the company on the valuation date, assumptions about future exit events and their timing are not needed. The advantage of this method is that it is easy to implement and does not require a significant number of assumptions or complex modeling.

However, because the CVM is not forward looking and does not consider the option-like payoffs of the share classes, its use is generally limited to two circumstances. First, the CVM could be employed when a liquidity event is imminent (such as a dissolution or an acquisition). The second situation might be when an early-stage company has made no material progress on its business plan, has had no significant common equity value created above the liquidation preference of the preferred shares, and for which no reasonable basis exists to estimate the amount or timing of when such value might be created in the future.

Generally speaking, once a company has raised an arm’s-length financing round (such as venture capital financing), the CVM is no longer an appropriate method.

Probability-Weighted Expected Return Method (PWERM)

The Probability-Weighted Expected Return Method is a multi-step process in which value is estimated based on the probability-weighted present value of various future outcomes. First, the valuation specialist works with management to determine the range of potential future outcomes for the company, such as IPO, sale, dissolution, or continued operation until a later exit date. Next, future equity value under each scenario is estimated and allocated to each share class. Each outcome and its related share values are then weighted based on the probability of the outcome occurring. The value for each share class is discounted back to the valuation date using an appropriate discount rate and divided by the number of shares outstanding in the respective class.

The primary benefit of the PWERM is its ability to directly consider the various terms of shareholder agreements, rights of each class, and the timing when those rights will be exercised. The method allows the valuation specialist to make specific assumptions about the range, timing, and outcomes from specific future events, such as higher or lower values for a strategic sale versus an IPO. The PWERM is most appropriate to use when the period of time between the valuation date and a potential liquidity event is expected to be short.

Of course, the PWERM also has limitations. PWERM models can be difficult to implement because they require detailed assumptions about future exit events and cash flows. Such assumptions may be difficult to support objectively. Further, because it considers only a specific set of outcomes (rather than a full distribution of possible outcomes), the PWERM may not be appropriate for valuing option-like payoffs like profit interests or warrants. In certain cases, analysts may also need to consider interim cash flows or the impact of future rounds of financing.

Option Pricing Model (OPM)

The Option Pricing Model treats each class of shares as call options on the total equity value of the company, with exercise prices based on the liquidation preferences of the preferred stock. Under this method, common shares would have material value only to the extent that residual equity value remains after satisfaction of the preferred stock’s liquidation preference at the time of a liquidity event. The OPM typically uses the Black-Scholes Option Pricing Model to price the various call options.

In contrast to the PWERM, the OPM begins with the current total equity value of the company and estimates the future distribution of outcomes using a lognormal distribution around that current value. This means that two of the critical inputs to the OPM are the current value of the firm and a volatility assumption. Current value of the firm might be estimated with a discounted cash flow method or market methods (for later-stage firms) or inferred from a recent financing transaction using the backsolve method (for early-stage firms). The volatility assumption is usually based upon the observed volatilities of comparable public companies, with potential adjustment for the subject entity’s financial leverage.

The OPM is most appropriate for situations in which specific future liquidity events are difficult to forecast. It can accommodate various terms of stockholder agreements that affect the distributions to each class of equity upon a liquidity event, such as conversion ratios, cash allocations, and dividend policy. Further, the OPM considers these factors as of the future liquidity date, rather than as of the valuation date.

The primary limitations of the OPM are its assumption that future outcomes can be modeled using a lognormal distribution and its reliance on (and sensitivity to) key assumptions like assumed volatility. The OPM also does not explicitly allow for dilution caused by additional financings or the issuance of options or warrants. The OPM can only consider a single liquidity event. As such, the method does not readily accommodate the right or ability of preferred shareholders to early-exercise (which would limit the upside for common shareholders). The potential for early-exercise might be better captured with a lattice or simulation model. For an in-depth discussion on the OPM, see our whitepaper A Layperson’s Guide to the Option Pricing Model at mer.cr/2azLnB.

Hybrid Method

The Hybrid Method is a combination of the PWERM and the OPM. It uses probability-weighted scenarios, but with an OPM to allocate value in one or more of the scenarios.

The Hybrid Method might be employed when a company has visibility regarding a particular exit path (such as a strategic sale) but uncertainties remain if that scenario falls through. In this case, a PWERM might be used to estimate the value of the shares under the strategic sale scenario, along with a probability assumption that the sale goes through. For the scenario in which the transaction does not happen, an OPM would be used to estimate the value of the shares assuming a more uncertain liquidity event at some point in the future.

The primary advantage of the Hybrid Method is that it allows for consideration of discrete future liquidity scenarios while also capturing the option-like payoffs of the various share classes. However, this method typically requires a large number of assumptions and can be difficult to implement in practice.

Conclusion

The methods for valuing private company equity-based compensation range from simplistic (like the CVM) to complex (like the Hybrid Method). In addition to the factors discussed above, the facts and circumstances of a particular company’s stage of development and capital structure can influence the complexity of the valuation method selected. In certain instances, a recent financing round or secondary sale of stock becomes a datapoint that needs to be reconciled to the current valuation analysis and may even prove to be indicative of the value for a particular security in the capital stack (see “Calibrating or Reconciling Valuation Models to Transactions in a Company’s Equity” on page 6). At Mercer Capital, we recommend a conversation early in the process between company management, the company’s auditors, and the valuation specialist to discuss these issues and select an appropriate methodology.

Originally published in the Financial Reporting Update: Equity Compensation, June 2019.

The Rise of FreightTech

To the lay person, transportation may seem like the farthest end of the spectrum from the technology industry – telephone orders and paper shipment tracking. But those in the know understand just how tech-enabled the industry has become. Advancements in machine learning, artificial intelligence, and predictive technology could have the power to disrupt the way goods are transported, stored, and tracked. And investors are clearly willing to take bets on that.

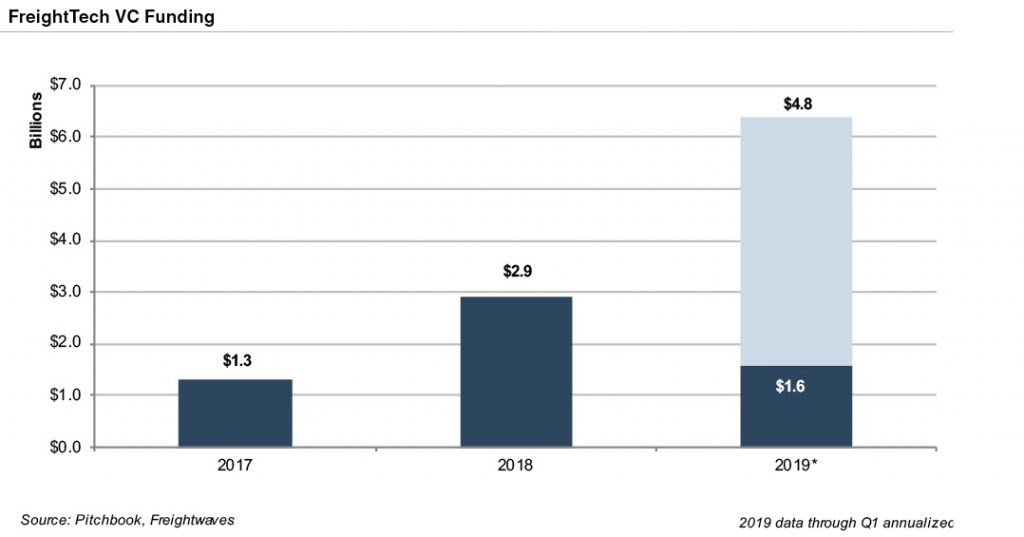

Over the past few years, FreightTech has emerged as its own category of technology. The level of excitement in the space grew in 2018 as global venture capital investment increased to $2.9 billion from $1.3 billion the prior year. FreightTech is on track for another year of exponential growth in 2019, with $1.6B of funding raised in the first quarter alone.

The willingness of industry participants to adopt logistics technology is evident as well. Corporate players and major OEMs have spun up innovation departments, startup accelerators, and investment arms in order to find and fund new technology. However, it’s not only the companies that directly benefit from this technology that are investing capital in the space. Technology players recognize the potential for returns on transportation investments, too. Alphabet’s venture capital arm, Capital G, led a $185 million investment in Convoy, a tech-enabled freight matching startup, at the end of 2018. The Series C round valued Convoy at $1.0 billion and brought the company’s total capital raise to $265 million. Softbank Vision Fund, known for making big bets on disruptive technology, got in on the game too. The fund invested $1.0 billion in Flexport, a digital platform for freight forwarding and logistics, at the start of the year. The investment valued the company at $3.2 billion.

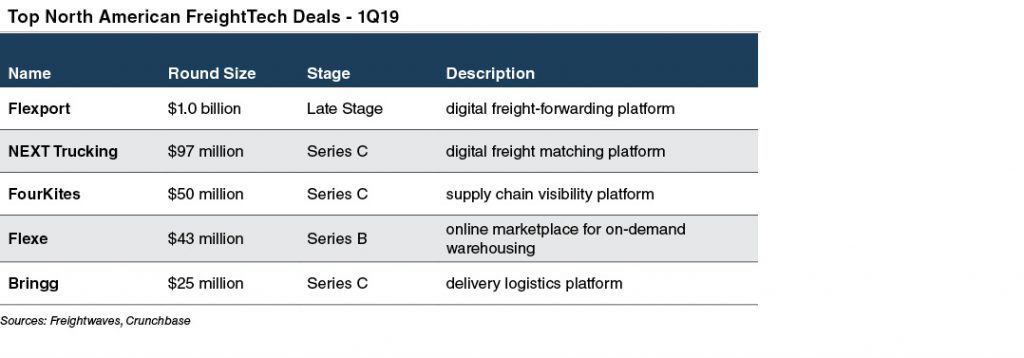

The table below shows the five largest North American FreightTech investments in the first quarter of 2019 by round size.

Investment in FreightTech has not only grown in terms of aggregate investment, but the average size of deal rounds has increased as well, mirroring the trends in the overall venture capital landscape. According to Morningstar, the average round size for a Series B round in the FreightTech industry increased 78% from $24.5 million in 2014 to $43.6 million in 2017.

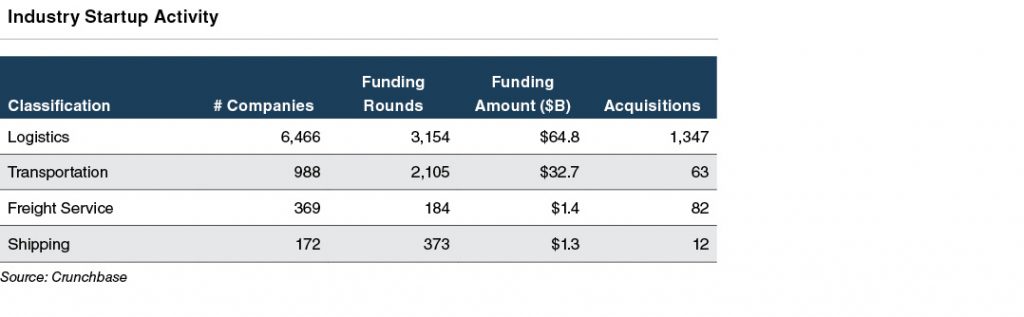

The classification of transportation and logistics startups differs, but it is clear that there is growing innovation in many different facets of the industry. It is evident that technological change in the freight transportation industry is about far more than just digitizing processes that once involved paper or fax machines. The application of advanced data and analytics to the transportation and logistics industry has the potential to change the global movement of freight.

Originally published in the Value Focus: Transportation & Logistics, First Quarter 2019.

NADC 2019 Spring Conference Recap

I recently attended the 2019 Spring Conference of the National Auto Dealers Counsel (NADC) in Dana Point, California. This article provides a couple of key takeaways from the day and a half sessions on the current conditions in the industry.

Vehicle Subscription Services

Car subscription services are becoming a popular alternative to leasing. Each service varies in structure and is operated by dealers, manufacturers, and third parties. Some offer reasonable traditional leases or allow customers to make monthly payments, but allow more flexibility/frequency in swapping vehicles for changing preferences and needs.

Some manufacturers are only initially offering subscription services regionally, or in specific markets (BMW and Mercedes-Benz are offering vehicle subscription services in the Nashville market).

Effect of Tariffs on New Vehicle Cost Differences

There has been a lot of talk in the news recently about impending tariffs in the auto dealer industry. Many unknowns and questions remain—Will President Trump enact tariffs? How will they affect the auto industry?

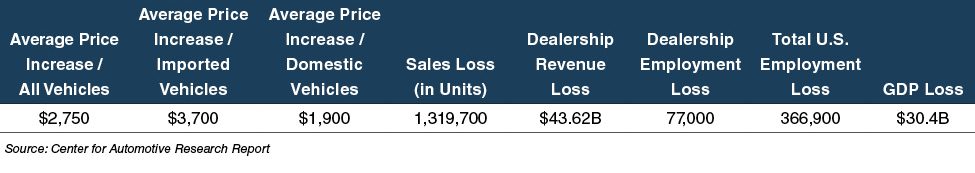

The Center for Automotive Research Report has compiled statistics to show the likely effects of tariffs on new/ used vehicle pricing, estimated losses for dealers, and projected employment and GDP loss (as seen below). With so much at stake, the auto dealer industry will keep a close eye on monitoring any new developments.

Tax Reform Act – Pass Through Entities vs. C Corporations

Amid the many changes that have resulted from the recent tax reform (the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA)), here are a few directly impacting the auto dealer industry:

- Interest Expense Deduction – Auto dealers are allowed to deduct total interest expense (including floor plan interest) up to 30% of their adjusted taxable income (“ATI”) and still recognize bonus depreciation on their qualified tangible property. If total interest expense is less than 30% of ATI, then the full amount is deductible along with bonus deprecation. If total interest expense is greater than 30% of ATI, auto dealers can deduct the full amount of interest expense, but lose the recognition of the bonus depreciation.

- Sale/Dissolution Planning – During the year of a potential sale, auto dealers should understand the ramifications of closing the sale earlier in the year versus later in the year. An earlier sale in the year could limit the wages for that year’s tax return that could offset a large ordinary income event from LIFO and depreciation recapture and other ordinary income. Whenever possible, contact your accountant or tax planning consultants to discuss the timing of a proposed sale.

- Pass Through Entities vs. C Corporations – While there are many other legal considerations for choosing your entity structure, the TCJA has had an impact on the valuation of C Corporations. Specifically, the value of C Corporations has increased by approximately 15%, all other factors, due to the decline in the corporate tax rates. To learn more about the impact of the changing corporate tax rates on C Corporation valuations, read this recent article.

Originally published in the Value Focus: Auto Dealer Industry Newsletter, Year-End 2018.

Measuring Up: Sorting Through the Puzzle of Dealership Metrics and Performance Statistics

This article explains dealership metrics and performance statistics–what they mean, how to evaluate them, and where a particular store stacks up. As always, performance measures are relative. We are relying upon averages provided by NADA as well as our experience working with auto dealers.1

A few key terms help frame our discussion:

- Variable operations refers to new vehicle department, used vehicle department, finance & insurance department, excluding warranty sales

- Fixed operations refers to service department (including warranty), parts department, and body shop where applicable

- Front-end gross margin refers to the gross profit margin realized on the sale of new and used vehicles; front-end margin typically varies in amounts between new and used vehicles depending on the franchise and types of cars being sold

- Domestic dealerships as defined by NADA typically consist of Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler/Dodge/Jeep/Ram/Fiat (FCA)

- Luxury dealerships as defined by NADA typically consist of Acura, Audi, BMW, Infiniti, Jaguar/Land Rover, Lexus, Mercedes Benz, Porsche, and Volvo

- Import dealerships typically consist of Acura, Audi, BMW, Hyundai, Infiniti, Jaguar/Land Rover, Kia, Lexus, Mazda, Mercedes Benz, Mitsubishi, Nissan, Porsche, Subaru, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Volvo

- Mass-market dealerships as defined by NADA typically consist of Chrysler/Dodge/Jeep/ Ram/Fiat (FCA), Ford, General Motors, Honda, Hyundai, Kia, Mitsubishi, Mazda, Subaru, Toyota, and Volkswagen

- High-line or ultra high-line dealerships may consist of Lamborghini, Rolls Royce, Bentley, Aston Martin, Lotus, McLaren, Maserati, etc.

Specifically, we are relying upon information from the average dealership profile for 2017 and 2018 from NADA.2

New Vehicle Department

For the average dealership profile, our experience has been that this department comprises between 50% – 60% (58% for 2017-2018 per NADA) of total gross sales. The front-end gross margin on new vehicles can vary over time and is somewhat controlled by the manufacturer. Typically, dealerships track and measure front-end gross margin on a per unit basis and can evaluate the overall performance of that figure by comparing it to prior years. Most domestic, import, or luxury dealerships experience a lower front-end gross margin on new vehicles than on used vehicles. Conversely, most high-line dealerships experience a higher front-end gross margin on new vehicles than on used vehicles.

New vehicles generally have a higher average retail selling price, lower front-end gross margins, and sell fewer units than used vehicles. These factors result in new vehicles comprising approximately 25% of total overall gross profits for an average dealership.

Used Vehicle Department

For the average dealership profile, our experience has been that this department comprises between 25% – 40% of total gross sales. These percentages can vary depending on franchise/dealership type and regional location. Like new vehicles, dealerships also track frontend gross profits on used vehicles on a per unit basis. Most domestic, import, or luxury dealerships experience a higher front-end gross margin on used vehicles than on new vehicles.

The sale of used vehicles should not be overlooked when assessing the value of a dealership. More often than not front-end gross margins on used vehicles will be higher than new vehicles. Additionally, the sale of both new and used vehicles put more cars in service and help drive profitability to fixed operations (to be discussed in next section). Based on our experience valuing new car dealerships, the range of used retail vehicles sold to new retail vehicles sold is 1.00 to 1.25. This figure can vary by dealership and can also be quite cyclical throughout the year. Further, our experience shows this ratio can climb to 1.5 to 1.6 when considering dealerships with successful wholesale used vehicle sales.

Used vehicles generally have a lower average retail selling price, higher front-end gross margins, and sell more units than new vehicles. These factors result in used vehicles comprising approximately 25% of total overall gross profits for an average dealership, or about even with the total overall gross profit contribution from new vehicles.

Fixed Operations

The long-term success of a dealership’s fixed operations is often tied to their effectiveness in selling new and used vehicles over time. These activities help to build brand in a market. Another critical factor in the success and level of profitability in the fixed operations is the auto industry cycle. In our last issue, we discussed the cyclicality of the industry not only in terms of certain months during the year, but also year-over-year.

Two such indicators of the auto industry life cycle are the SAAR and the average age of car. As shown on page 14 of the newsletter, the monthly SAAR began to level off in late 2018 and into the first few months of 2019 (despite a slight spike in March 2019) evidencing slower new light vehicle sales. Additionally, per our previous newsletter, the average age of cars in service was approximately ten years.

Both factors foreshadow that fixed operations of successful dealerships should experience an uptick in the short-term and mitigate the moderate/sluggish new vehicle sales. When customers hold onto their cars longer, they are less likely to spend money on a new or used vehicle, but their maintenance needs on their current vehicle will likely increase.

For the average dealership profile, our experience suggests that the service department comprises between 10% – 15% of total gross sales. However, this department is typically the most profitable in terms of a percentage of sales. The combination of much higher margins on lower sales results in the service department averaging 45% – 50% of total gross profits, or a much higher contribution level than new or used vehicles.

Conclusion

All dealerships are not created equally. This article is a general discussion on various dealership metrics and performance statistics. Each statistic is relative and not to be viewed in a vacuum. Hopefully, we have provided a better understanding of the various departments, including fixed vs. variable operations and their contribution to overall profitability and the eventual value of a store. A graphic display of historical profitability and other metrics are discussed later in the newsletter. For an understanding of how your dealership is performing along with an indication of what your store is worth, contact us. We are happy to discuss your needs in confidence.

1 The data and discussion are based generally on average dealership profiles and do not pertain specifically to domestic dealerships, import dealerships, ultra high-line dealerships, etc. Specific types of dealerships and their regional location could have different performance metrics and criteria.

2 It’s important to note that other national sources of Blue Sky multiple data (Haig Partners and Kerrigan Advisors) classify the categories of dealerships slightly different from NADA, so all comparisons and discussion should be done in general terms.

Originally published in the Value Focus: Auto Dealer Industry Newsletter, Year-End 2018.

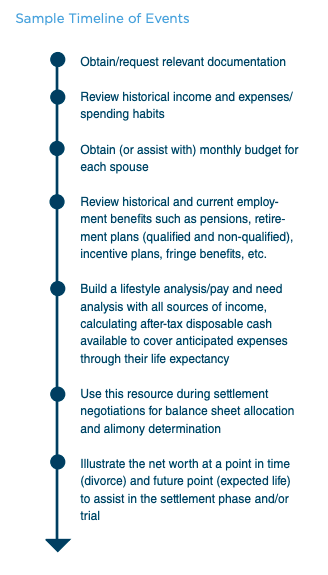

How to Present Complex Finance to Judges

Originally presented at the 2019 AAML/BVR National Divorce Conference in Las Vegas, in this session, Z. Christopher Mercer, FASA, CFA, ABAR delves into more than 30 years of experience presenting complex valuation and damages issues to judges and juries. One of the key ideas of effective communication is the KISS principle, or “keep it simple, stupid.” The question is, how can we do that? Chris provides the techniques and templates necessary to communicate your position, and your opponent’s position, in such a way that judges can hone in on and understand the most important information and why it’s important.

Labor Shortage in Trucking Sector

Driver Shortage

The trucking industry is wedged between a rock and a hard place when it comes to driver recruitment. Trucking companies are simultaneously exploring self-driving technology, while still convincing new entrants to the labor market that commercial driving is a career choice that will pay off. Punctuating the less-than-glamorous work and lifestyle conditions of the occupation, those entering the labor force realize that the career path could be upended in the near-term by the economic cycle and disrupted in the long term by the impending evolution of autonomous transportation. With several companies (like Tesla) beginning deployment of self-driving trucks, and numerous others deep in development of the technology, young workers may fear choosing a vocation that trucking companies are actively planning to automate.

Rob Sandlin, CEO of Patriot Transportation, emphasized these challenges in the company’s third quarter earnings call, “Management spends a good deal of time dealing with these issues surrounding driver shortage, including advertising, recruiting, compensation, dispatcher training and productivity among others.” With the tightening of the labor market, companies have found new ways to attract talent including investments in newer and more reliable assets, in-house training programs, incentive bonuses, and, of course, a simple increase in wages.

Executives at many of the largest trucking companies dedicated time in their third quarter investor calls and presentations to this issue. PAM identified several unique recruitment initiatives in its November corporate presentation. The company is taking advantage of temporary visitor qualifications through the B1 Visa program to increase labor capacity. This program allows commercial drivers with Mexican residence temporary entry to the United States for truck delivery. Additionally, the company’s new driver-friendly initiatives promote lifestyle and career improvements. Its “Driver Life-Cycle” program provides dedicated driver experience with a path towards ownership through a lease-to-own set up.

Patriot mentioned significant changes to its recruitment efforts, as well. “In the latter part of fiscal 2018, we implemented a significant change to our hiring process, we added [a] driver advocate position and introduced productivity-based driver pay, all in an effort to attract and retain drivers. We are encouraged by the increased number of drivers hired and in training since these implementations, and we’ll continue to monitor our progress for any needed adjustments to our plan.”

Mechanic Shortage

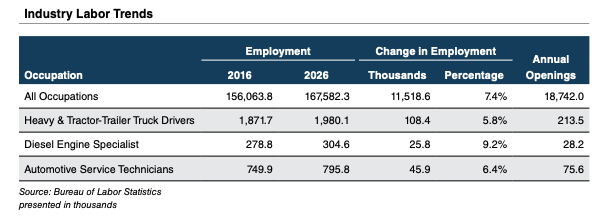

The driver shortage (which is estimated to reach 108,000 by 2026) has sparked major shifts in the way hiring and training are conducted in the industry. While this shortage will hurt shippers until autonomous technology is fully developed, the long-term problem may actually lie in another labor pool: service technicians.

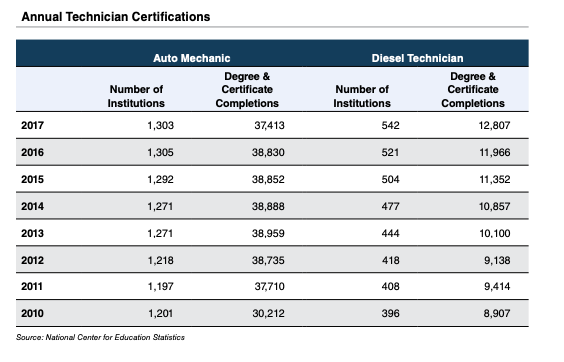

As new truck designs increase the level of technology on board, those who service them will have to develop more tech-focused expertise. Additional sensors, predictive technology, and, of course, autonomy will evolve the role of the truck mechanic as they start spending more time with computers than wrenches. While technical colleges and certificate programs continue to produce a skilled workforce, the supply of service technicians has not kept pace with the increasing demand.

Trucking companies have had to adapt to the shifting labor force trends and find new ways to fulfill maintenance needs. Like driver scarcity, mechanic shortages have caused companies to seek alternatives to traditional labor sourcing, from outsourcing labor needs to developing training programs.

Overall, employment in the transportation and warehousing industry grew 3.5% from October 2017 to October 2018, adding more than 183,700 jobs. Nearly 37,000 of these jobs were in the trucking industry, which experienced a 2.5% increase in employment over the prior year. The transportation industries are adding jobs faster than the overall non-farm economy, which experienced a more modest 1.7% increase in employment.

Despite labor pressures in the industry, economic activity and transportation demand remain strong. While executives will continue to monitor driver and mechanic shortages, the outlook for trucking in 2019 appears optimistic. John Roberts III, CEO of J.B. Hunt, summed up the industry sentiment well on the company’s third quarter earnings call.

Just final comment on the people side of things. Driver hiring has been a challenge. It’s been a challenge in the past. It presented us with the challenge like we have never seen before this year. In fact, our unseated need number got as high as [it’s] ever been. In about the last 60 days, we’ve seen that number come down a little bit through a number of internal efforts. And I think overall pay in the industry is starting to catch up a little bit. And so I think more people are becoming interested. But we’re making progress there and feel confident we’ll continue to get through that. Good year, some challenges, and frankly, we’re looking forward to heading into 2019.

Originally published in the Value Focus: Transportation & Logistics, Fourth Quarter 2018.

Net Interest Margin Trends and Expectations

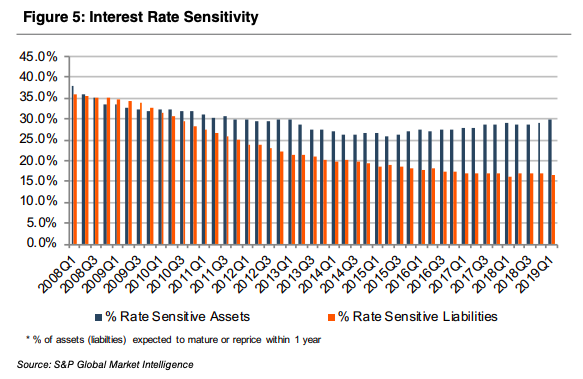

Since Bank Watch’s last review of net interest margin (“NIM”) trends in July 2016, the Federal Open Market Committee has raised the federal funds rate eight times after what was then the first rate hike (December 2015) since mid2006. With the past two years of rate hikes and current pause in Fed actions, it’s a good vantage point to look at the effect of interest rate movements on the NIM of small and large community banks (defined as banks with $100 million to $1 billion of assets and $1 billion to $10 billion of assets).

As shown in Figure 1, NIMs crashed in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis, primarily because asset yields fell much quicker than banks could reprice term deposits. NIMs subsequently rebounded as the asset refinancing wave subsided while banks were able to lower deposit rates. A several year period then occurred in which asset yields grinded lower at a time when deposit rates could not be reduced. This period was particularly tough for commercial banks with a high level of non-interest bearing deposits.

Since rate hikes started, the NIM for both small and large community banks have increased about 20bps through year-end 2018 before experiencing some pressure in early 2019. The nine hikes by the Fed to a target funds rate of 2.25% to 2.50% amounts to a 225bps increase.

At first pass, the expansion in the NIMs is less than might be expected; however, there are always a number of factors in bank balance sheets that will impact the NIM, including:

- Loan Floors. Many Libor- and prime-based commercial loans had floors that required 100-150bps of hikes before the floors were “out-of-the-money.”

- Competition. Intense competition for loans in an environment in which bonds yielded very little resulted in pressure in the margin over a base rate as bank and non-bank lenders accepted lower margins in order to make loans.

- Asset Mix. Community banks located in rural and semi-rural areas tend to have low loan-to-deposit ratios and, therefore, have not benefited as much as peers located in and around MSAs that are “loaned-up.” Nonetheless, net loans as a percentage of assets among community banks increased by an average of 15bps each quarter since year-end 2016 while bond portfolios declined.

- Loan Mix. Community banks tend to have somewhat more of their loan portfolios allocated to residential mortgages and CRE than regional banks. As a result, it will take much longer for these mostly fixed-rate assets to reprice than Libor-based C&I portfolios.

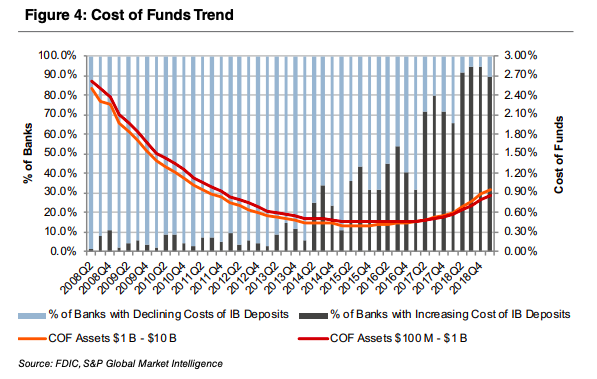

- Deposit COF. In recent quarters the marginal cost of funds (“COF”) has become expensive as depositors who came to accept being paid essentially nothing for their money began to demand more competitive rates once the Fed Funds rate approached 2%.

- Deposit Mix. In addition to depositors demanding higher rates, a mix shift from non-interest bearing and very low-yielding transaction accounts into higher paying money markets and time deposits has pushed the COF higher, too, in recent quarters.

Fed to Cut Rates?

Recent incremental pressure on NIMs notwithstanding, community banks’ balance sheets were poised to take advantage of rising rates the past several years. The outperformance of bank stocks beginning in November 2016 reflected several factors, including an economic and regulatory backdrop that would allow the Fed to raise rates further and faster, and thereby support NIM expansion.

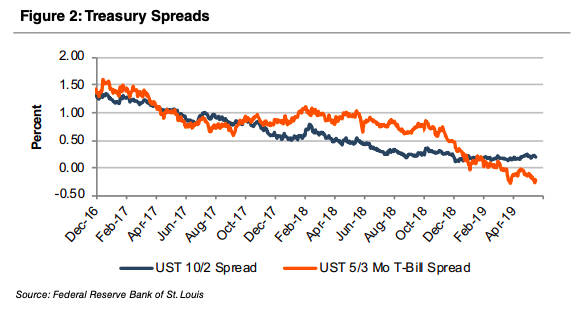

The underperformance of bank stocks since last fall reflects investor concern that this tailwind is ending in addition to more general concerns about what a possible economic slowdown implies for credit costs. Telltale signs include the inversion of the Treasury yield curve and yields on the two-year and five-year Treasuries that, as of the date of the drafting of this article, are below the low-end of the Fed Funds target range.

Also, the spot and forward curves for 30-day Libor imply the Fed will cut the Funds target rate and other short-term policy rates one or two times by early 2020 (or stated differently, the December rate hike was a mistake).

The Federal Funds rate, the predominant influence on short-term interest rates, has remained unchanged since year-end 2018 at a target range of 2.25%–2.50% due to concerns about lower inflation figures and what they may forewarn about future economic growth as reflected in falling U.S. Treasury yields. The FOMC reiterated its wait-and-see approach on May 1. However, the sand appears to be shifting beneath the Fed’s feet.

The Wall Street Journal’s most recent Economic Forecasting Survey revealed an increasing belief that the Fed’s next move will be to cut rates. 51% of respondents said that a rate cut would be the next move, up from 44% in April. 25.5% replied that the next rate raise would occur in 2020 or later. Fed officials have maintained their stance that a rate move in either direction will not occur soon.

The Importance of Deposits and Next Steps

As deposit costs initially lagged, but more recently moved with short-term interest rate hikes, the composition of a bank’s deposit base and funding structure has become increasingly important. As shown in Figure 4, the percentage of banks experiencing a rising cost of interest bearing deposits has steadily increased. Total funding costs have nearly doubled since year-end 2016 as depositors have reoriented funds toward accounts offering higher rates. Banks searching for funding either must engage in intense deposit competition or tap into higher-cost sources such as wholesale funding.

Going forward community banks may face a modest reduction in NIMs because the yield curve is flat and the cost of incremental funding is expensive. Some community banks will choose to slow loan growth in order to protect margins; others will accept a lower margin. The predicament demonstrates yet again why deposit franchises are a key consideration for acquirers as banks with low cost deposit franchises and excess liquidity are particularly attractive in the current market.

Originally published in Bank Watch, May 2019.

Employee Benefits Agency Consolidation and Valuation

Lucas Parris, CFA, ASA-BV/IA, vice president, co-presented the session, “Employee Benefits Agency Consolidation and Valuation” with Mike Strakhov (Live Oak Bank) at the 2019 Workplace Benefits Renaissance Conference in Nashville, TN (February 20-22, 2019).

A short description of the session can be found below.

Insurance agency merger and acquisition activity has been at historic levels for the past few years. Employee benefit agency transactions represent a significant number of these annually. This session will address the current state of agency consolidation including trends, who’s buying and who’s selling and the overall impact to employee benefits distribution. We’ll also identify and discuss the important characteristics that drive value of an employee benefits agency.

The Importance of Fairness Opinions in Transactions

It has been 34 years since the Delaware Supreme Court ruled in the landmark case Smith v. Van Gorkom, (Trans Union), (488 A. 2d Del. 1985) and thereby made the issuance of fairness opinions de rigueur in M&A and other significant corporate transactions. The backstory of Trans Union is the board approved an LBO that was engineered by the CEO without hiring a financial advisor to vet a transaction that was presented to them without any supporting materials.

Why would the board approve a transaction without extensive review? Perhaps there were multiple reasons, but bad advice and price probably were driving factors. An attorney told the board they could be sued if they did not approve a transaction that provided a hefty premium ($55 per share vs a trading range in the high $30s).

Although the Delaware Supreme Court found that the board acted in good faith, they had been grossly negligent in approving the offer. The Court expanded the concept of the Business Judgment Rule to include the duty of care in addition to the duties to act in good faith and loyalty. The Trans Union board did not make an informed decision even though the takeover price was attractive. The process by which a board goes about reaching a decision can be just as important as the decision itself.

Directors are generally shielded from challenges to corporate actions the board approves under the Business Judgement Rule provided there is not a breach of one of the three duties; however, once any of the three duties is breached the burden of proof shifts from the plaintiffs to the directors. In Trans Union the Court suggested had the board obtained a fairness opinion it would have been protected from liability for breach of the duty of care.

The suggestion was consequential. Fairness opinions are now issued in significant corporate transactions for virtually all public companies and many private companies and banks with minority shareholders that are considering a take-over, material acquisition, or other significant transaction.

When to Get a Fairness Opinion

Although not as widely practiced, there has been a growing trend for fairness opinions to be issued by independent financial advisors who are hired to solely evaluate the transaction as opposed to the banker who is paid a success fee in addition to receiving a fee for issuing a fairness opinion.

While the following is not a complete list, consideration should be given to obtaining a fairness opinion if one or more of these situations are present:

- There is only one offer for the bank and competing bids have not been solicited

- Competing bids have been received that are different in price and structure (e.g., cash vs stock)

- The shares to be received from the acquiring bank are not publicly traded and, therefore, the value ascribed to the shares is open to interpretation

- Insiders negotiated the transaction or are proposing to acquire the bank

- Shareholders face dilution from additional capital that will be provided by insiders

- Varying offers are made to different classes of shareholders

- There is concern that the shareholders fully understand that considerable efforts were expended to assure fairness to all parties

What’s Included (and What’s Not) in a Fairness Opinion

A fairness opinion involves a review of a transaction from a financial point of view that considers value (as a range concept) and the process the board followed. The financial advisor must look at pricing, terms, and consideration received in the context of the market for similar banks. The advisor then opines that the consideration to be received (sell-side) or paid (buy-side) is fair from a financial point of view of shareholders (particularly minority shareholders) provided the analysis leads to such a conclusion.

The fairness opinion is a short document, typically a letter. The supporting work behind the fairness opinion letter is substantial, however, and is presented in a separate fairness memorandum or equivalent document.

A well-developed fairness opinion will be based upon the following considerations that are expounded upon in an analysis that accompanies the opinion:

- A review of the proposed transaction, including terms and price and the process the board followed to reach an agreement

- The subject company’s capital table/structure

- Financial performance and factors impacting earnings

- Management’s current year budget and multi-year forecast

- Valuation analysis that considers multiple methods that provide the basis to develop a range of value to compare with the proposed transaction price

- The investment characteristics of the shares to be received (or issued), including the pro-forma impact on the buyer’s capital structure, regulatory capital ratios, earnings capacity, accretion/dilution to EPS, TBVPS, DPS

- Address the source of funds for the buyer and any risk funding may not be available

It is important to note what a fairness opinion does not prescribe, including:

- What the highest obtainable price may be

- The advisability of the action the board is taking versus an alternative

- Where a company’s shares may trade in the future

- How shareholders should vote a proxy

- The reasonableness of compensation that may be paid to executives as a result of the transaction

Due diligence work is crucial to the development of the fairness opinion because there is no bright line test that consideration to be received or paid is fair or not. Mercer Capital has nearly four decades of experience in assessing bank (and non-bank) transactions and the issuance of fairness opinions. Please call if we can assist your board.

Originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, April 2019

Kress v. U.S. Denies S Corporation Premium and Accepts Tax-Affecting

The issue of a premium for an S corporation at the enterprise level has been tried in a tax case, and the conclusion is none.

In Kress v. United States (James F. Kress and Julie Ann Kress v. U.S., Case No. 16-C-795, U.S. District Court, E.D. Wisconsin, March 25, 2019), the Kresses filed suit in Federal District Court (Eastern District of Wisconsin) for a refund after paying taxes on gifts of minority positions in a family-owned company. The original appraiser tax-affected the earnings of the S corporation in appraisals filed as of December 31, 2006, 2007, and 2008. The court concluded that fair market value was as filed with the exception of a very modest decrease in the original appraiser’s discounts for lack of marketability (DLOMs).

Background on GBP

The company was GBP (Green Bay Packaging Inc.), a family-owned S corporation with headquarters in Green Bay, Wisconsin. The company experienced substantial growth after its founding in 1933 by George Kress. A current description of the company, consistent with information in the Kress decision, follows.

Green Bay Packaging Inc. is a privately owned, diversified paper and packaging manufacturer. Founded in 1933, this Green Bay WI based company has over 3,400 employees and 32 manufacturing locations, operating in 15 states that serve the corrugated container, folding carton, and coated label markets.

Little actual financial data is provided in the decision, but GBP is a large, family-owned business. Facts provided include:

- Although GBP has the size to be a public company, it has remained a family-owned business as envisioned by its founder.

- About 90% of the shares are held by members of the Kress family (a Kress descendant is the current CEO), with the remaining 10% owned by employees and directors.

- The company paid annual dividends (distributions) ranging from $15.6 million to $74.5 million per year between 1990 and 2009. While historical profitability information is not available, the distribution history suggests that the company has been profitable.

- Net sales increased during the period 2002 to 2008.

Hoovers provides the following (current) information, along with a sales estimate of $1.3 billion:

Green Bay Packaging is the other Green Bay packers’ enterprise. The diversified yet integrated paperboard packaging manufacturer operates through 30 locations. In addition to corrugated containers, the company makes pressure-sensitive label stock, folding cartons, recycled container board, white and kraft linerboards, and lumber products. Its Fiber Resources division in Arkansas manages more than 210,000 acres of company-owned timberland and produces lumber, woodchips, recycled paper, and wood fuel. Green Bay Packaging also offers fiber procurement, wastepaper brokerage, and paper-slitting services. (emphasis added)

The court’s decision states that the company’s balance sheet is strong. The company apparently owns some 210 thousand acres of timberland, which would be a substantial asset. GBP also has certain considerable non-operating assets including:

- Hanging Valley Investments (assets ranging from $65 – $77 million in the 2006 to 2008 time frame)

- Group life insurance policies with cash surrender values ranging from $142 million to $158 million during this relevant period and $86 million to $111 million net of corresponding liabilities

- Two private aircraft, which on average, were used about 50% for Kress family use and about 50% for business travel

GBP was a substantial company at the time of the gifts in 2006, 2007, and 2008. We have no information regarding what portion of the company the gifts represented, or how many shares were outstanding, so we cannot extrapolate from the minority values to an implied equity value.

The Gifts and the IRS Response

Plaintiffs James F. Kress and Julie Ann Kress gifted minority shares of GBP to their children and grandchildren at year-end 2006, 2007, and 2008. They each filed gift tax returns for tax years 2007, 2008 and 2009 basing the fair market value of the gifted shares on appraisals prepared in the ordinary course of business for the company and its shareholders. Based on these appraisals, plaintiffs each paid $1.2 million in taxes on the gifted shares, for a combined total tax of $2.4 million. We will examine the appraised values below.

The IRS challenged the gifting valuations in late 2010. Nearly four years later, in August 2014, the IRS sent Statutory Notices of Deficiency to the plaintiffs based on per share values about double those of the original appraisals (see below). Plaintiffs paid (in addition to taxes already paid) a total of $2.2 million in gift tax deficiencies and accrued interest in December 2014. It is nice to have liquidity.

Plaintiffs then filed amended gift tax returns for the relevant years seeking a refund for the additional taxes and interest. With no response from the IRS, Plaintiffs initiated the lawsuit in Federal District Court to recover the gift tax and interest they were assessed. A trial on the matter was held on August 3-4, 2017.

The Appraisers

The first appraiser was John Emory of Emory & Co. LLC (since 1999) and formerly of Robert W. Baird & Co. I first met John in 1987 at an American Society of Appraisers conference in St. Thomas. He is a very experienced appraiser, and was the originator of the first pre-IPO studies. Emory had prepared annual valuation reports for GBP since 1999, and his appraisals were used by the plaintiffs for their gifts in 2006, 2007, and 2008.

The Emory appraisals had been prepared in the ordinary course of business for many years. They were relied upon both by shareholders like the plaintiffs as well as the company itself.

The next “appraiser” was the Internal Revenue Service, where someone apparently provided the numbers that were used in establishing the statutory deficiency amounts. The court’s decision provides no name.

The third appraiser was Francis X. Burns of Global Economics Group. He was retained by the IRS to provide its independent appraisal at trial. As will be seen, while his conclusions were a good deal higher than those of Emory (and Czaplinski below), they were substantially lower than the conclusions of the unknown IRS appraiser. The IRS went into court already giving up a substantial portion of their collected gift taxes and interest.

The fourth appraiser was hired by the plaintiffs, apparently to shore up an IRS criticism of the Emory appraisals. Nancy Czaplinski from Duff & Phelps also provided an expert report and testimony at trial. Emory’s report had been criticized because he employed only the market approach and did not use an income approach method directly. Czaplinski used both methods. It is not clear from the decision, but it is likely that Czaplinski was not informed regarding the conclusions in the Emory reports prior to her providing her conclusions to counsel for plaintiffs.

While the court did not agree with all aspects of the work of any of the appraisers, the appraisers were treated with respect in the opinion based on my review. That was refreshing.

The Court’s Approach

The court named all the appraisers, and began with an analysis of the Burns appraisals (for the IRS). In the end, after a thoughtful review, the court did not rely on the Burns appraisals in reaching its conclusion.

After reviewing the essential elements of the Burns appraisals, the court provided a similar analysis of the Emory appraisals. The court was impressed with Emory’s appraisals, and appeared to be influenced by the fact that the appraisals were done in the ordinary course of business for GBP and its shareholders. The court surely noticed that the IRS must have accepted the appraisals in the past since Emory had been providing these appraisals for many years. Other Kress family members had undoubtedly engaged in gifting transactions in prior years.

The court then reviewed the Czaplinski appraisal. While the court was light on criticisms of the Czaplinski appraisals, it preferred the methodologies and approaches in the Emory appraisals.

Interestingly, the entire analysis in the decision was conducted on a per share basis, so there was virtually no information about the actual size or performance or market capitalization of GBP in the opinion. We deal with the cards that are dealt.

Summary of the Court’s Discussion

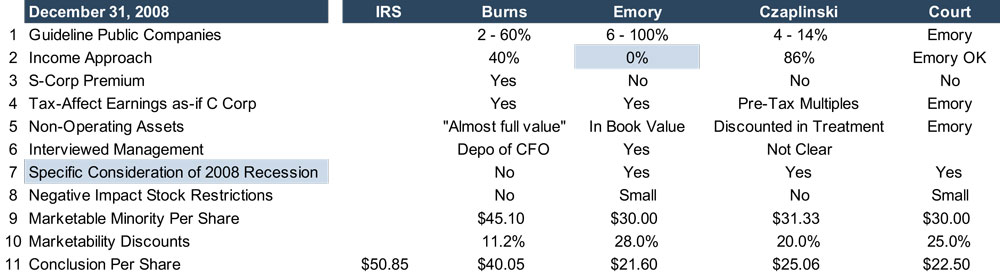

As I read the court’s decision, there were ten items that were important in all three appraisals, and an additional item that was important in the December 31, 2008 appraisal. Readers will remember the Great Recession of 2008. It was important to the court that the appraisers consider the impact of the recession on the outlook for 2009 and beyond in their appraisals for the December 31, 2008 date.

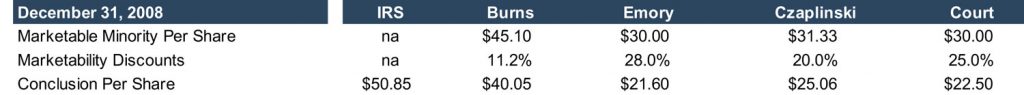

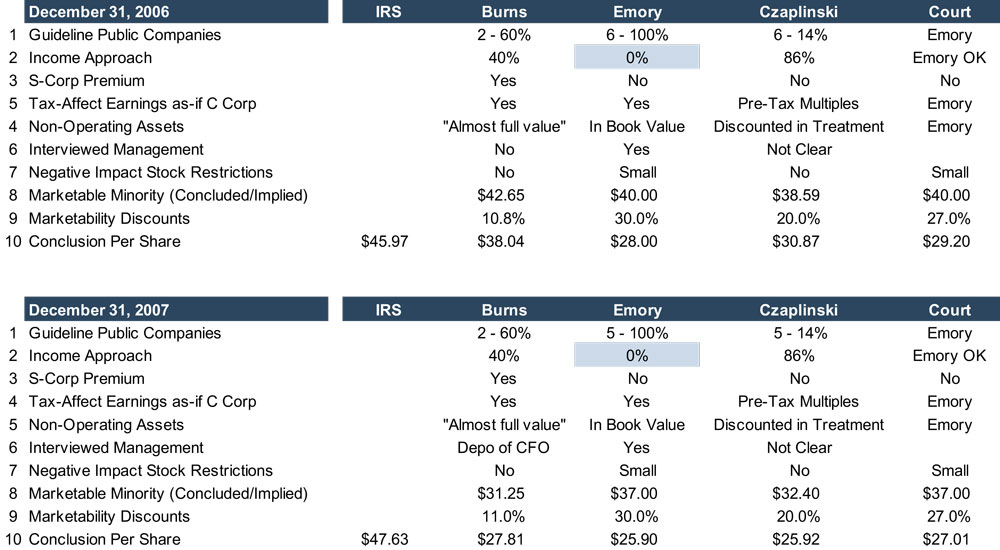

In the interest of time and space, we will focus on the appraisals as of December 31, 2008 in the following discussion. The summaries of the other appraisals are provided without comment at the end of this article. The December 31, 2008 summary follows. We deal with the eleven items that were discussed or implied in the subsections below.

There are six columns above. The first provides the issue summary statements. The next four columns show the court’s reporting regarding the eleven items found in the 2008 appraisal based on its review of the reports of the appraisers. Note that there is no detail whatsoever for the rationale underlying the IRS conclusion for the Statements of Deficiency. The final column provides the court’s conclusion. To the extent that items need to be discussed together, we will do so.

Items 1 and 2: The Market Approach and the Income Approach

All the appraisers employed the market approach in the appraisals as of December 31, 2008 (and at the other dates). They looked at the same basic pool of potential guideline companies but used different companies and a different number of companies in their respective appraisals.

The court was concerned that the use of only two comparable companies in the Burns report was inadequate to capture the dynamics of valuation. In fact, Burns used the same two guideline companies for all three appraisals, and the court felt that this selective use did not capture the impact of the 2008 recession on valuation (Item 7). He weighed the market approach at 60% and the income approach at 40% in all three appraisals.

Czaplinski used four comparable companies in her 2008 appraisal and weighted the market approach 14% (same in her other appraisals). Her income approach was weighted at 86%.

Emory used six guideline companies in the 2008 appraisal. While he used the market approach only, the court was impressed that “he incorporated concepts of the income approach into his overall analysis.” This comment was apparently addressing the IRS criticism that the Emory appraisals did not employ the income approach.

Items 3 and 4: The S-Corp Premium/Treatment

The case gets interesting at this point, and many readers and commentators will talk about its implications.

At the enterprise level, both Burns and Emory tax-affected GBP’s S corporation earnings as if it were a C corporation. This is notable for at least two reasons: