How Badly do Job Cuts Affect the Value of Texas Energy Companies?

Texas energy companies continue to cut jobs at a shocking rate. According to the Houston Business Journal, nearly 40,000 people working for three of the world’s largest oilfield services firms have lost their jobs in the last six months, and even more layoffs are anticipated in the near future. Cuts have also occurred in the upstream and manufacturing sectors.

About the Cuts

Halliburton Co. has already cut 9,000 jobs, which amounts to 10 percent of its workforce. Schlumberger Ltd. has cut 20,000 jobs, which is approximately 15 percent of its workforce, and Baker Hughes Inc. has cut 10,500 jobs, which accounts for 17 percent of its workforce. All of these companies also reported losses or a significant decrease in earnings for Q1.

In the upstream sector, Newfield Exploration Co. has announced that it plans to merge two of its units and close its Denver office. Hercules Offshore Inc. has cut its workforce by almost 40 percent, and Linn Energy LLC plans to close its Denver office, eliminating 52 jobs in the process.

Are These Layoffs Necessary?

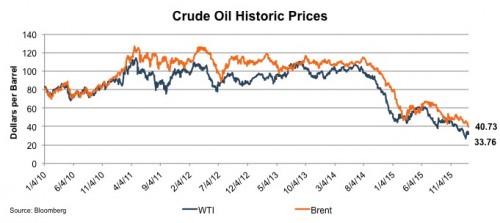

For oilfield service providers, recent job cuts have been largely unavoidable. Oil prices have been declining in recent months, leading to significant revenue loss for companies in this sector. In fact, the Wall Street Journal reports that prices for U.S.-traded crude oil reached a six-year low in mid-March of this year.

For companies in the upstream sector, however, layoffs may not have been a necessity. These companies have not been affected by oil price declines as dramatically as oilfield service providers, so it’s possible that they are simply using the declines as an excuse to “shed fat” and boost efficiency.

Effects on Valuation

Layoffs may impact a company’s performance and value in a number of ways. Some of the possible effects of layoffs include:

- Bad Press: Job loss is associated with a number of negative implications for employees, which can lead to bad press for the company.

- Uncertainty: Downsizing inspires feelings of uncertainty among remaining employees, investors and any other party with a stake in the company’s future.

- Employment Restructuring Expenses: Layoffs often involve employment restructuring expenses, which leads to increased expenses and decreased profits. In fact, several of the companies discussed reported losses after implementing job cuts.

The immediate effect of job cuts on company values is undoubtedly negative. However, cuts are often made in the hope that lower overhead costs and increased efficiency will eventually boost profits and, hence, the company’s overall worth. Thus, the effect of these cuts on the future of Texas energy companies remains unknown.

Looking into the Past

This is not the first time oil prices have dropped enough to have a noticeable impact on the industry. After peaking in 1980, crude oil prices fell steadily for the next six years. The demand for oil was greatly reduced, and businesses in this industry were losing money. In response, they cut back on exploration and drilling significantly, leading to tens of thousands of layoffs.

Oil prices eventually rebounded after the 1980s oil glut. However, because companies had laid off so many workers, they were not prepared to handle the boom that followed. This caused a number of problems for companies in the industry, as they were forced to scramble for employees with the experience and expertise necessary for success in the open positions. Unfortunately, many of the best workers had left oil for good, and potential recruits were wary of joining an industry that seemed so volatile.

In light of this history, some companies with cash reserves are attempting to curb the number of job cuts in order to prevent staffing issues when prices improve. However, for many of the smaller companies, layoffs are unavoidable.

No one can say for certain what the future holds. If the market rebounds quickly, companies that have implemented heavy job cuts may find themselves struggling. If prices remain low, however, companies in this industry that have tried to curb job cuts may have no choice but to cut even more workers loose. Regardless of what happens, achieving a complete recovery from this crisis will not be easy.

This article was originally published in Valuation Viewpoint, May 2015.

Preferences and FinTech Valuations

2015 was a strong year for FinTech. For those still skeptical, consider the following:

- All three publicly traded FinTech niches that we track (Payments, Solutions, and Technology) beat the broader market, rising 11 to 14% compared to a 1% return for the S&P 500;

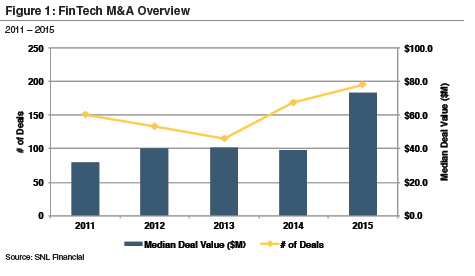

- FinTech M&A volume and pricing rose sharply over recent historical periods with 195 announced deals and a median deal value of $74 million in 2015 (Figure 1);

- A number of notable fundings for private FinTech companies occurred with roughly $9.0 billion raised among approximately 130 U.S. FinTech companies in larger funding rounds (only includes raises over $10 million).

One of the more notable FinTech events in 2015 was Square’s IPO, which occurred in the fourth quarter. Square is a financial services and mobile payments company that is one of the more prominent FinTech companies with its high profile founder (Jack Dorsey, the Twitter co-founder and CEO) and early investors (Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia Capital). Its technology is recognizable with most of us having swiped a card through one of their readers attached to a phone after getting a haircut, sandwich, or cup of coffee. Not surprisingly, Square was among the first FinTech Unicorns, reaching that mark in June 2011. Its valuation based on private funding rounds sat at the top of U.S.-based FinTech companies in mid-2015.

So all eyes in the FinTech community were on Square as it went public in late 2015. Market conditions were challenging then (compared to even more challenging in early 2016 for an IPO), but Square had a well-deserved A-list designation among investors. Unfortunately, the results were mixed. Although the IPO was successful in that the shares priced, Square went public at a price of $9 per share, which was below the targeted range of $11 to $13 per share. Also, the IPO valuation of about $3 billion was sharply below the most recent fundraising round that valued the company in excess of $5 billion.

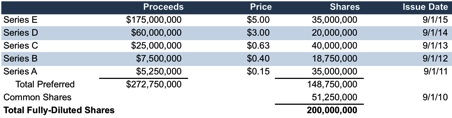

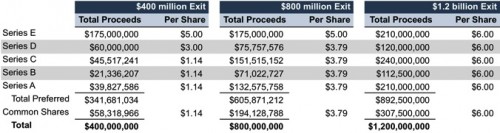

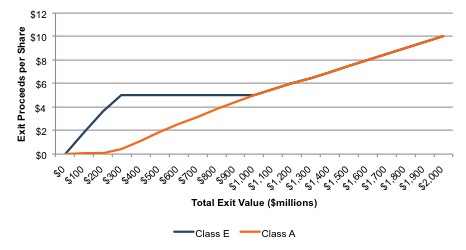

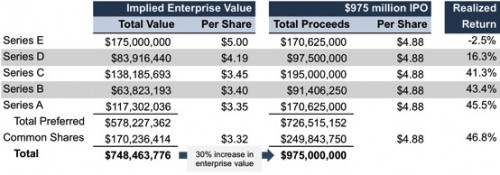

In the category its great pay if you can get it, most Series E investors in the last funding round had a ratchet provision that provided for a 20% return on their investment, even if the offering price fell below the $18.56 per share price required to produce that return. The ratchet locked in through the issuance of additional shares to the Series E investors. The resulting dilution was borne by other investors not protected by the ratchet.

On the flip side the IPO was not so bad for new investors. Square shares rose more than 45% over the course of the opening day of trading and then traded in the vicinity of $12 to $13 per share through year-end. With the decline in equity markets in early 2016, the shares traded near the $9 IPO price in mid-February.

IPO pricing is always tricky—especially in the tech space—given the competing demands between a company floating shares, the underwriter, and prospective shareholders. The challenge for the underwriter is to establish the right price to build a sizable order book that may produce a first day pop, but not one that is so large that existing investors are diluted. According to MarketWatch, less than 2% of 2,236 IPOs that priced below the low end of their filing range since 1980 saw a first day pop of more than 40%. By that measure, Square really is a unique company.

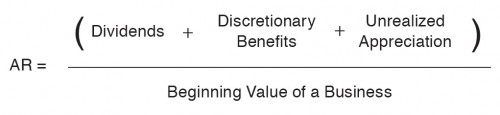

One notable takeaway from Square’s experience is that the pricing of the IPO as much as any transaction may have marked the end of the era of astronomical private market valuations for Unicorn technology companies. The degree of astronomical depends on what is being measured, however. We have often noted that the headline valuation number in a private, fundraising round is often not the real value for the company. Rather, the price in the most recent private round reflects all of the rights and economic attributes of the share class, which usually are not the same for all shareholders, particularly investors in earlier fundraising rounds. As Travis Harms, my colleague at Mercer Capital noted: “It’s like applying the pound price for filet mignon to the entire cow – you can’t do that because the cow includes a lot of other stuff that is not in the filet.”

While a full discussion of investor preferences and ratchets is beyond the scope of this article, they are fairly common in venture-backed companies. Recent studies by Fenwick & West of Unicorn fundraisings noted that the vast majority offered investors some kind of liquidation preference. The combination of investor preferences and a decline in pricing relative to prior funding rounds can result in asymmetrical price declines across the capital structure and result in a misalignment of incentives. John McFarlane, Sonos CEO, noted this when he stated: “If you’re all aligned then no matter what happens, you’re in the same boat… The really high valuation companies right now are giving out preferences – that’s not alignment.”

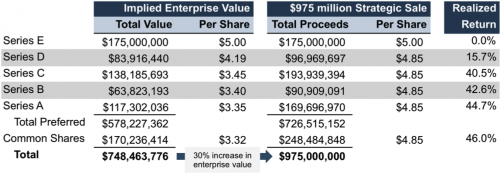

A real-world example of this misalignment was reported in a New York Times story in late 2015 regarding Good Technology, a Unicorn that ended up selling to BlackBerry for approximately $425 million in September 2015. While a $425 million exit might be considered a success for a number of founders and investors, the transaction price was less than half of Good’s purported $1.1 billion valuation in a private round. The article noted that while a number of investors had preferences associated with their shares that softened the extent of the pricing decline, many employees did not. “For some employees, it meant that their shares were practically worthless. Even worse, they had paid taxes on the stock based on the higher value.”

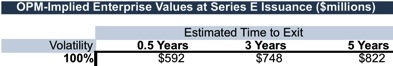

As the Good story illustrates, the valuation process can be challenging for venture-backed technology companies, particularly those with several different share classes and preferences across the capital structure, but these valuations can have very real consequence for stakeholders, particularly employees. Thus, it is important to have a valuation process with formalized procedures to demonstrate compliance with tax and financial reporting regulations when having valuations performed. Certainly, the prospects for scrutiny from auditors, SEC, and/or IRS are possible but very real tax issues can also result around equity compensation for employees.

Given the complexities in valuing venture-backed technology companies and the ability for market/investor sentiment to shift quickly, it is important to have a valuation professional that can assess the value of the company as well as the market trends prevalent in the industry. At Mercer Capital, we attempt to gain a thorough understanding of the economics of the most recent funding round to provide a market-based “anchor” for valuation at a subsequent date. Once the model is calibrated, we can then assess what changes have occurred (both in the market and at the subject company) since the last funding round to determine what impact if any that may have on valuation. Call us if you have any questions.

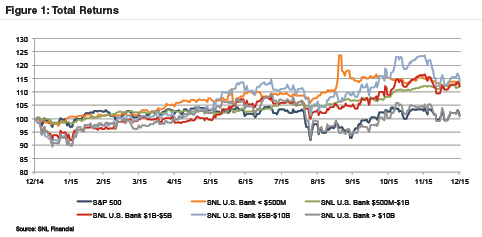

2015: A Good Year for Banks

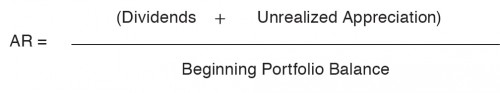

After weak broad market performance in the first quarter of the year and slow advances during the summer, U.S. stocks generally saw amplified returns in the fourth quarter of 2015. The largest banks (those with over $50 billion in assets) generally performed in line with broad market trends, but most banks outperformed the market with total returns on the order of 10% to 15% for the year (Figure 1).

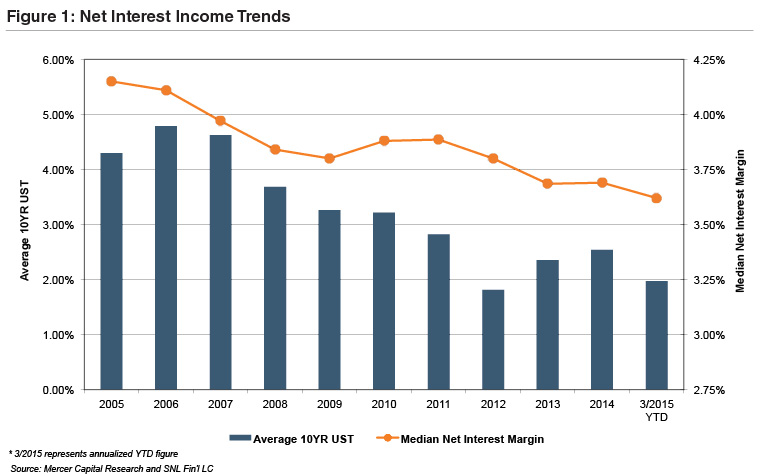

Bank stock performance improved markedly in the fourth quarter as speculation following the FOMC’s September meeting suggested rate increases may begin in the fourth quarter. In mid-December, the FOMC met again and, after seven years of its zero interest rate policy, announced an increase in the target fed funds rate. The shift in monetary policy is expected to gradually improve strains on banks’ net interest margins and should be most apparent for banks with more asset-sensitive balance sheets, though community banks that may have made more loans with longer fixed terms or loan floors may experience some tightening in the short term.

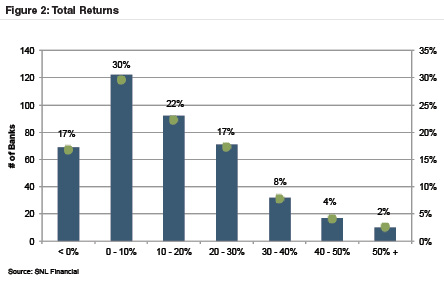

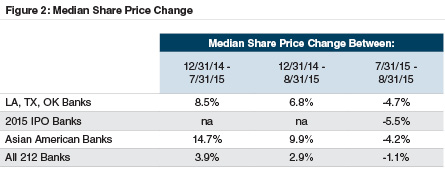

Bank returns generally averaged around 0% to 30% in 2015, though 17% of the U.S. banks analyzed (traded on the NASDAQ, NYSE, or NYSE Market exchanges for the full year) realized negative total returns. These included banks continuing to deal with high levels of NPAs; banks that are located in oil-dependent areas such as Louisiana and Texas; and some banks that have been active acquirers that missed Street expectations. On the other end, a few high performers in 2015 include merger targets as well as banks that have seen more success from acquisition activity (Figure 2).

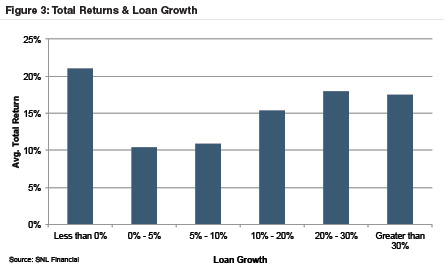

One of the primary factors contributing to stronger returns in 2015 was loan growth. Banks with loan growth over 10% exhibited above-average returns, while those with slower growth tended to exhibit lower returns, with the exception of banks that shrank their portfolios during the year, though for these banks the higher returns likely reflected prior years’ underperformance that was priced into the stocks (Figure 3).

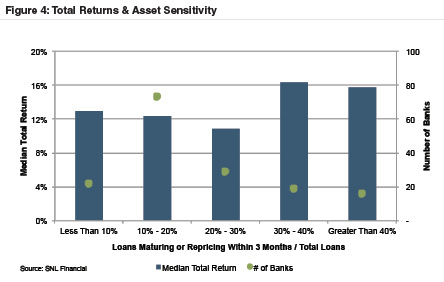

Asset-sensitive banks also outperformed in 2015. While asset sensitivity is difficult to evaluate from publicly available data, we measured asset sensitivity by the proportion of loans maturing or repricing in less than three months from September 30, 2015, relative to total loans (both obtained from FR Y-9C filings). Limiting the analysis to publicly traded banks with assets between $1 billion to $5 billion reveals that the most asset sensitive banks returned about 16% in 2015, or 400 basis points more than less asset sensitive banks (Figure 4).

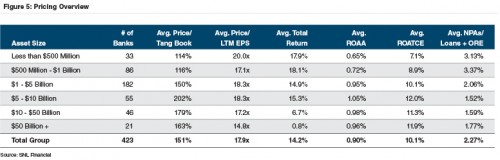

Though the smallest banks generally realized the highest returns in 2015, pricing multiples were strongest for banks with assets between $1 and $10 billion, which generally saw better profitability than the smaller banks. Year-over-year, pricing multiples generally remained flat from 2014 (Figure 5).

Mercer Capital is a national business valuation and financial advisory firm. Financial Institutions are the cornerstone of our practice. To discuss a valuation or transaction issue in confidence, feel free to contact us.

Energy Future Holdings: Valuation Issues Hover Over Bankruptcy Proceedings

When Energy Future Holdings (“EFH”) and certain of its subsidiaries entered into a pre-arranged reorganization under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code on April 29, there were (and remain) a myriad of issues that require resolution for the largest generator, distributor and retail electricity provider in Texas. How should debtor-in-possession (“DIP”) financing be allocated? How and when will restructuring priority be given to various creditors? Is a “tax-free” spin of Texas Consolidated Energy Holdings (“TCEH”) a viable option? What is to be done about Oncor? The list goes on. At the heart of those questions, and of the bankruptcy, are valuation issues that have and likely will continue to permeate throughout the process.

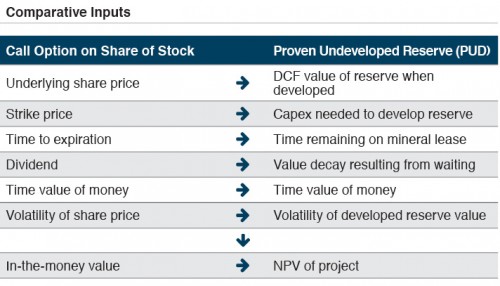

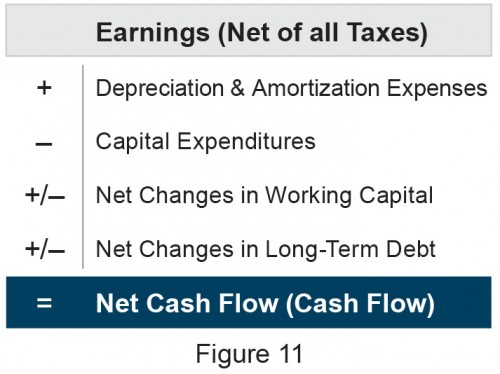

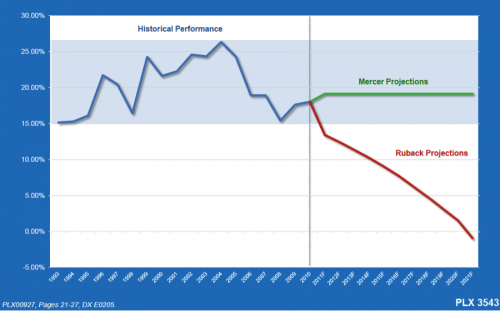

What is EFH – and more specifically its subsidiaries TXU Energy, Luminant and Oncor – worth? That’s the $42 billion question. Valuation professionals can utilize a number of tools at their disposal to attempt to answer that question, including income methods such as discounted cash flow analysis and market methods such as comparative transactions and publicly traded peer analysis. How those methods are applied, along with their underlying economic and financial assumptions, will be closely examined and almost certainly challenged among the stakeholders.

At issue are EFH’s three distinct business units: (i) Luminant which is the merchant power unit; (ii) TXU Energy which is the retail electric unit, and (iii) Oncor’s power delivery business. Luminant and TXU Energy are unregulated, while Oncor is regulated.

A few of the critical existing and potentially emerging valuation issues in EFH’s Chapter 11 process include things like (i) premises of value, (ii) regulatory issues as they pertain to pricing and rate setting, (iii) consolidated vs. non-consolidated restructuring scenarios and (iv) development of projections and cash flows. All of these issues have interplay with each other and they are certainly not exclusive when it comes to valuation considerations for as complex an organization as EFH. In addition we will look to instructive prior electric company bankruptcies, such as Mirant and Dynegy, to help navigate these waters as well.

Premise of Value: Reorganization Value vs. Fair Market Value

“Being in bankruptcy is like being in a fishbowl,” said Sander “Sandy” Esserman, a partner at Stutzman, Bromberg, Esserman & Plifka who was involved in the Mirant Corporation bankruptcy. One of the most meaningful and thematic aspects stakeholders and observers will be viewing in that fishbowl will be the standard of value lens that one peers through. Standard of value considerations will be front and center at EFH’s division Texas Competitive Electric Holdings (“TCEH”), where creditors are disputing EFH’s restructuring strategy that could wipe out billions of dollars of debt.

There are two premises of value to consider: fair market value and reorganization value. The fair market value standard is more of an as-is where-is proposition, which posits that the value of a company is a reflection of what the current marketplace will pay for it.

This standard is used (often successfully) in reorganization plans and liquidation scenarios where a sale of assets or companies is a viable and appropriate solution to the parties. This could be unlikely in EFH’s situation.

According to EFH management, under certain scenarios, a Section 363 sale could trigger tax liabilities of over $6 billion. However, in the midst of Chapter 11 reorganizations, fair market value has been criticized as overemphasizing the “stigma” of bankruptcy, and thus undervaluing a debtor. Esserman concurred that undervaluation can happen, citing American Airlines and Lyondell as examples of companies that emerged out of Chapter 11 and quickly saw stock prices (and thus enterprise values) increase.

The other key standard is reorganization value, which can be defined as the enterprise value of the reorganized debtor. This more futuristic premise takes into account the effects of the bankruptcy process and its benefits to the value of the debtor(s). The difficulty of this can be in its proper application and timing. The Mirant bankruptcy, whereby the court issued an exhaustive memorandum opinion on the valuation efforts, put significant weight on the reorganization value standard and, as such, utilized exit financing and non-distressed equity returns as assumptions in its valuation opinion. This is almost certainly the posture that unsecured creditors will be taking in regard to EFH.

Regulatory & Consolidation Issues: How Does Oncor Fit In?

One of the negotiated items pre-bankruptcy was whether or not to consider a “consolidated” bankruptcy for EFH, meaning including Oncor in the plan.

This is an important consideration. Oncor is not a debtor in the Chapter 11 case, but its value is a relevant component to the restructuring. TXU is Oncor’s largest customer, and it is regulated by the Public Utility Commission of Texas (“PUC”). Due to its regulated status, Oncor is restricted from making distributions to EFH under certain conditions.

Oncor also has an independent board of directors, not to mention certain structural and operational aspects used to enhance Oncor’s credit quality – known as “ring-fencing” measures that further isolate it from EFH. That said, Oncor is profitable and distributions represent an all-important cash inflow to EFH as a means to fund creditors, perhaps as adequate protection to secured creditors or as payment to unsecured creditors.

The rates set by the PUC impact those measures. This brings about the question of where will the influence of the bankruptcy court end and the regulatory authorities begin? Actions by one may or may not influence the other. We do not pretend to know or even want to speculate on what will transpire in respect to this, but however those rates and dividends out of Oncor change, it will impact the value to EFH and its creditors.

The competitive side of EFH’s business, TCEH, is in a highly competitive business that buys and sells a commodity product. Its rates are not set and have fluctuating inputs that have significant impact on valuations.

How the marketplace views Luminant and TXU Energy is different than how it views Oncor, so it might make sense to treat each entity individually, with separate cash flow projections, pricing and market assumptions. That said, there are other consolidated, multi-faceted public electric companies that may provide good valuation benchmarks.

It is notable that in the Mirant bankruptcy the court considered and utilized public comparable companies. However, with the specific structural, tax and regulatory issues involved with EFH and its subsidiaries, one has to be careful not to generalize comparative aspects of these companies, which the Mirant court emphasized.

Projections: Reaching a Consensus or a Battle of Contending Plans?

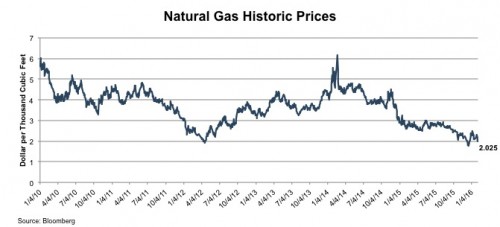

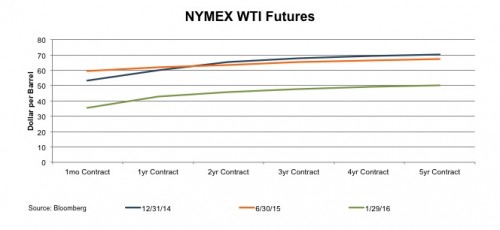

When private equity investors KKR, TPG and Goldman Sachs bought EFH in 2007 for more than $8 billion in equity, it was widely seen as a bullish take on natural gas prices. Back then, investor projections anticipated rising Henry Hub prices. They were wrong. EFH characterized its misfortune this way in their first day motions: “In October 2007, the main ingredients for EFH’s financial success were robust and steady economic growth…natural gas prices that were not expected to significantly decline over the long term. Since 2007, however, overall economic growth was reduced…and wholesale electricity prices have significantly declined.”

New discoveries, hydraulic fracturing and the 2008 recession all led to a drop in natural gas prices. The challenge that needs to be undertaken now is attempting to project prices in today’s environment as these prices form the baseline for any financial or discounted cash flow analysis. Coal prices play a meaningful role as well.

Opinions vary widely on this and therein it is perhaps the most challenging valuation aspect in this entire case. Where will natural gas prices go? Some parties are more optimistic than others and this optimism could fuel the basis for competing reorganization plans. For EFH’s part, it would not surprise people if management took a conservative view on gas prices, having already been burned on prior projections. The stakes are high. Cash flow sensitivity to even slight variations in assumed prices could mean the difference between an unsecured creditor being made whole or getting very little.

One path the court could take is having industry subject matter experts help key industry variables and form a baseline for a projection. The underlying assumptions in the cash flow projections would be ultimately built upon those assumptions.

Even if agreement is reached there, the bottom line cash flow could still vary widely based on cost structure, rates of return and future tax benefits from prior net operating losses (TCEH reported $3.0 billion of pre-tax losses in 2013). The net operating losses, depending on what reorganization plan the court adopts, could prove to be an enormous swing factor as well. They could possibly be worth billions under one scenario or they could potentially be worthless depending on the tax treatment of the plan.

Summary

Valuation issues are front and center of the EFH bankruptcy. How the ultimate reorganization plan plays out will be critical. Many valuation aspects can be structured in a settlement. However, even in bankruptcy environments, there are economic, financial and market issues that still fuel the undergirding drivers to maximizing value for all stakeholders. No investor wants the short end of a stick. Depending on how the valuation issues play out there might be a chance that EFH has a long enough stick for everyone to grasp. Time will tell.

This article was published in The Texas Lawbook on July 10, 2014.

The Oil and Gas Shift is Impacting the Industry in a Few Key Areas

Anybody who has been to a gas pump in the last several months can tell you that the energy industry is currently in the throes of change. Prices are falling to lows that they haven’t seen in almost a decade and the industry itself is being impacted in a large number of different ways. The changing face of economics and the marketplace has presented an entirely new set of challenges that businesses will have to adapt to in order to thrive well into the future.

The Changing Face of Economics and the Marketplace

Another significant change that will impact the oil and gas industries in 2015 and beyond has to do with current market fluctuations that will affect profitability. It’s no secret that oil prices started plummeting in 2014 and show no signs of slowing down. Bernstein Research, for example, estimates that a full 1/3 of all shale projects in the United States become unprofitable once prices fall below $80.

This is a case-by-case basis, however, and is not blanket fact. The Bakken formation in North Dakota, for example, will still be profitable so long as prices do not fall below $42 per barrel – according to the IEA. ScotiaBank’s own research indicates that prices have to stay between $60 to $80 per barrel for the Bakken formation to remain profitable.

Changes in Production and Demand

A large part of the reason why oil prices are continuing to fall has to do with two other significant changes that are impacting the industry: namely, changes to the total amount of oil that the United States and Canada are producing, as well as changes to the demand for oil in areas of the world like Europe and Asia.

According to the International Energy Agency (also commonly referred to as the IEA), shale production in the United States is expected to shift dramatically in the coming years. In scenarios both where oil prices remain roughly where they are and where they continue to fall even farther, the IEA predicts that shale production will still continue to grow, just at a much slower rate than it has been in the last several years. To put that into perspective, production is still expected to increase an additional 950,000+ barrels per day throughout the entirety of 2015.

Another important factor to consider has to do with infrastructure with regards to existing investments. There are a large number of energy companies that have already paid a great deal of money purchasing land, obtaining necessary permits and performing other tasks necessary to drilling. Even if oil prices continue to fall, these companies can’t necessarily curb back on their production or they fear losing an even greater investment than initially feared. In these types of situations, the true “break even” price in production varies depending on the operator and their tolerance versus the amount of debt that they’ve taken on. Even still, it may be too early to tell in many cases how firm those tolerances really are.

The boom in increased oil production in the United States and Canada has created something of a tricky situation for the industry as a whole. After sinking a huge amount of money into infrastructure over the last several years, businesses now have to contend with falling prices that show no signs of slowing down. In order to adapt they will have to look for ways to embrace new technology and streamline production in order to stay profitable well into the future and to break through into a bold new era for the industry as a whole.

This article was originally published in Valuation Viewpoint, January 2015.

Does the Clippers $2 Billion Deal Make Sense?

In recent court testimony, Bank of America – Merrill Lynch (“BoA”) revealed its bid book (“Project Claret”) prepared for potential buyers of a NBA franchise, the Los Angeles Clippers (“Clippers”). We are going to analyze elements within the Project Claret document with a particular focus on the revenue estimate of the local media contract renewal in 2014.

Let’s look at BoA’s estimate of local media revenues primarily related to television content. BoA forecasted television rights payment in June 2014 year-end at $25.8 million from the current contract projecting it to $125 million for a new local media contract. Michael Ozanian of Forbes recently estimated the 2014 new contract amount to most likely be closer to $75 million. I agree with Mr. Ozanian for the following reasons:

- If the Los Angeles Lakers (“Lakers”), back in 2011, signed a local media television rights contract for $5 billion over 25 years, then the average is approximately $200 million a year. Typically these contracts have annual escalation clauses and if the total payout is $5 billion, then the amount in 2012 is close to $100 million for the Lakers. You need to escalate that to about $110 million in 2014.

- The television ratings of the Lakers are multiples of the Clippers and cable subscribers ultimately pay for the right’s fees. So if you are a sophisticated buyer of sports content, like Fox Broadcasting Company or Time Warner Cable, are you going to pay the same dollar amount for the Clippers as you did for the Lakers? The Clippers have ½ the television ratings of the Lakers (1.28 vs 2.72) in the current year. To quote a recent Variety article, “This is believed to be the closest the Clippers have come to the Lakers in television ratings since the 1999-2000 season.” Additionally, the Lakers experienced a very poor win/loss record in the 2013-2014 season. If one analyzed their historical results, the Clippers have less than 1/3 of the viewership as the Lakers (121,000 vs 390,000) last year.

Therefore, how much will the Clippers realistically get in 2014 with the new contract? $75 million is approximately 68% of our estimated Lakers deal amount and seems generous based on the raw ratings numbers. However, if we utilize the Forbes estimate of $75 million in 2014 and the other BoA revenue estimates for game admissions ($62.3 million) and other team revenue ($136.8 million), the total revenue estimate for the Clippers would be $274.1 million in 2014 versus the $324.1 million utilized in BoA Project Claret.

If one assumes a multiple of 5x revenues, which is the high end of multiples paid for an NBA team to date, the indicated enterprise value estimate is $1.370 billion, a far cry from $2 billion. Additionally, many times when dealing with estimates of future results (in this case an estimate of future revenue) the valuation multiple applied should be lower than actual transaction multiples. These multiples are calculated based on historical revenues, which are usually lower than future estimates.

It seems clear to us that based on the data available the $2 billion price from Steve Ballmer is a good deal for the Sterling Trust.

This article was originally published in Valuation Viewpoint, August 2014.

Exploring the Major League Baseball Value Explosion

From 2000 to 2005, Major League Baseball teams were selling for much less than National Football League teams, i.e., typically under $200 million. Most of the MLB teams were showing losses at the time, and there was limited interest in buying the teams that did come up for sale. But the buying and selling environment changed dramatically in 2012, with the Los Angeles Dodgers selling for over $2.15 billion in a spirited auction with sixteen initial bidders.1

What has caused this explosion in MLB prices and do these high prices make sense?

In this article, I attempt to answer this question as I discuss MLB franchise price/value changes in the last fifteen years and whether these dramatic jumps in prices/values make economic/market sense.

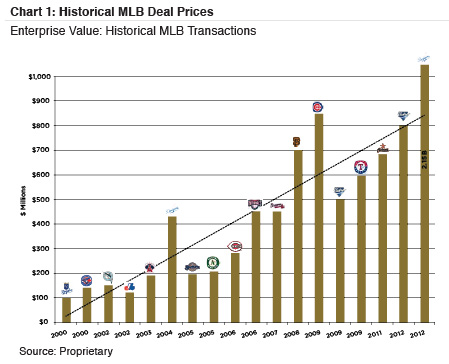

First, I illustrate actual transaction prices for MLB teams in the early 2000s. I then show the significant increases—starting in 2008—leading to the blockbuster $2.15 billion Dodgers deal in 2012.

I then demonstrate the value changes published by Forbes Magazine and discuss key economic changes in the industry (i.e. MLB) that have contributed to these price jumps of twice—and sometimes three times—the 2005 prices for MLB franchises.

Finally, I explore the actual financials for the Texas Rangers and a history of the prices paid for the Rangers over the years.

For definition purposes, when we discuss values, we are always discussing enterprise (equity + debt), not equity values, and when we discuss revenue multiples, we are discussing total revenues from team/franchise and stadium interests, but excluding regional sports network (RSN) interests.

Deal Prices and MLB Values Estimated by Forbes Magazine

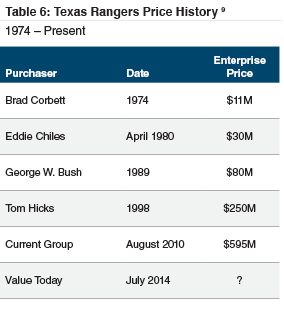

As Chart 1 shows, enterprise prices for MLB teams from 2000 to 2005 were less than $200 million, except for the 2004 Dodgers deal, which came in at $430 million. In 2006, two transactions increased to the low $400 million range. In 2008, a San Francisco Giants deal indicated $700 million, and the Chicago Cubs in 2009 were sold for over $800 million. In 2009 during the “Great Recession,” a smaller market team, the San Diego Padres, transacted at $500 million. Also in 2009, the Texas Rangers sold at $595 million during a bankruptcy bidding war. Finally, the chart shows the big jump with the bankruptcy auction prices of the L.A. Dodgers and their stadium and land at $2.15 billion in 2012.

Changes in Revenue Multiples

Unlike entities in other industries, major league sports teams are usually valued using a market approach rather than an income approach. Most of their enterprise values are referenced as a multiple of team and stadium revenues.

The multiples in revenues paid for actual transactions in the early 2000s were in the 2.0 times to 2.5 times range, but recent deals have been over 4.0 times revenues. The recent 4.0 times multiple reflects anticipated growth in revenues since sophisticated and well-heeled buyers are anticipating significant future revenue growth.

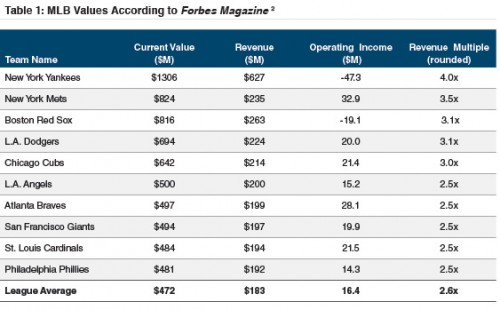

In Table 1, Forbes estimates are developed by Forbes editors utilizing public sources, their proprietary methods of estimating team revenues and expenses, and their judgment as to the valuation multiple to be applied to their revenue estimates.3

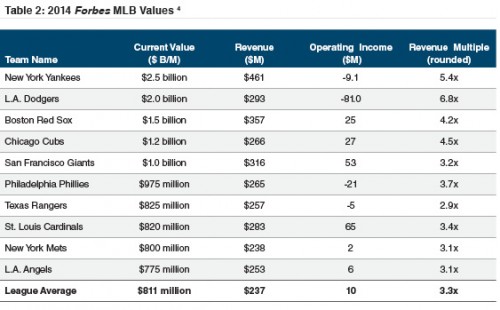

By 2014 (see Table 2), Forbes average MLB value estimate had jumped to $811 million and had a 3.3 times multiple. The values ranged from $2.5 billion for the Yankees to $485 million for the Tampa Bay Rays.

The average revenue estimates for the league have only increased from $183 million to $237 million or thirty percent. Yet the average valuation multiple increased from 2.6 times to 3.3 times causing the average team value to increase sixty-four percent. What caused this significant increase? The answer: potential for increased local revenues due to an explosion in media rights fees.

Meteoric Media Rights Fee Increases

As mentioned earlier, recent media rights fees for local broadcasts of MLB teams have increased three to five times that of older contracts. These older contracts may have been ten years in length, but the new ones can be in force as long as twenty-five years.

Unlike the total revenues for NFL teams and, to a lesser extent, those of the NBA, local media rights fees make up the majority of revenues for MLB teams. In many markets, the content providers (cable and satellite companies) are vying for a unique live product that can differentiate them in the marketplace. This competition has caused bidding wars for TV and other media rights to MLB teams.

The largest current local MLB media contract was negotiated by the L.A. Dodgers and was recently approved by MLB. In this contract, the L.A. Dodgers will reportedly receive $6 billion after a revenue-sharing split with MLB. This equates to an average of $240 million a year over twenty-five years. The old Dodgers contract was approximately $50 million dollars in its last year.

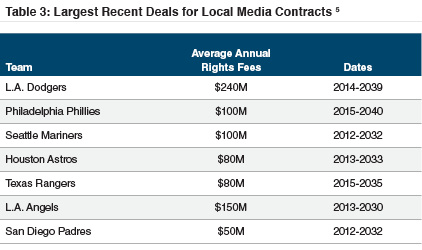

The next highest are the Texas Rangers and the Houston Astros at $80 million a year on average. In addition, the national TV MLB has jumped also—see Table 3.

It should be noted that part of the massive increase in payments to the L.A. Dodgers by Time Warner Cable is covered by Time Warner’s plan to pass the costs on to other pay TV providers, including Direct TV, Dish Network, Charter Communications, and Cox Communications.

Currently, Time Warner Cable and their providers are deadlocked on the price increases they will pay for airing the L.A. Dodger games. The providers contend that Time Warner’s cable price for their L.A. Dodger sports channel is too high. How this negotiation is settled will affect prices other providers pay nationwide. For example, the Houston Astros RSN has not been picked up by many of the local providers and the RSN has been forced to file for bankruptcy.

Table 4 shows the changes in the MLB National media contracts with the various networks. We note that the ESPN contracts increased from $296 million a year to $700 million a year. The Fox contract increased from $257 million a year to $525 million a year, etc. In short, the new national contracts increased by 120 percent from the other contract.

At the height of the recession, the San Diego Padres sold for $500 million in 2009. It resold in 2012 for $800 million due primarily to a major jump in a local media contract.

Are the teams making so much money that they warranted such a much higher price based on profits? The answer, surprisingly, is “no, not really.”

Case Study: Texas Rangers

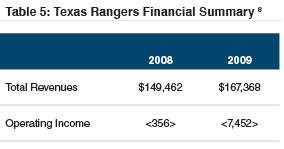

The Texas Rangers sale in 2009 to the highest bidder out of bankruptcy court7 is a good example (Table 5).

Note that these numbers were prior to any regional media contract increases now scheduled to begin with the 2015 season.

Also note that annual amounts shown in the both the local and national contracts are averages and the initial year of the contract is usually much less than the average price shown.

All teams are subject to a player salary cap, which come with significant penalties if violated. So conceptually, if your revenues go up $50 million in a particular year, that amount could fall to the bottom line. How much is $50 million of profit worth to buyers whose primary value driver is not cash flow? It could be $500 million. It could be $1 billion. Which then causes people to wonder how much profit do these teams actually make?

The answer is that many lose money—some significant amounts. Many people ask why anyone would pay these amounts to buy teams if they do not make a reasonable profit.

There are two main answers to that:

- Every buyer has a different motivation.

- Few of us can look at “investments” through the lens of a multi-billionaire to whom a $10 to $50 million annual loss is not significant to their financial well-being.

Texas Rangers Price History

The Texas Rangers also provide a good example of transaction price changes in the MLB. Table 6 shows the transactions in the team since 1974.

Please note that in the $595 million 2010 transaction, the team was making very little money and with signing bonuses deducted, was not cash flow positive. What is the value of this team, considering such facts?

Conclusion

The intensity of local revenues for MLB has created a perfect storm for MLB teams as the media engages in a buying frenzy for live local sports entertainment.

Multiples of 4.0 times revenues are now becoming the new normal versus 2.0 times prior to 2006 driven by local revenue growth with media leading the way. Media contracts are increasing three to five times the annual amounts negotiated in the early to mid-2000s. The outlook for increased local media contracts will create new and higher MLB club transactions for years to come.

But what about value creation? In the case of the Dodgers, if their media revenue increases up hypothetically $200 million a year from the previous contract, how much increase in value will that create? Could it be an extra billion dollars or more? At the end of the day, these local media contract increases, coupled with the new increased national media contracts, generally tend to support the new much higher level of MLB prices.

Obviously, the smaller markets do not enjoy the same increases as the major markets like Los Angeles and New York, etc., but their new contracts will increase in multiples of older contracts i.e., from $15 to $20 million a year to $50 million plus as media providers compete for the exclusive content that live sports provides.

This article was originally published in The Value Examiner, September/October 2014.

Endnotes

- Brian Solomon, “$2 Billion Dodgers Sale Tops List of Most Expensive Sports Team Purchases Ever,” Forbes Magazine, March 29, 2012, http://www.forbes. com/sites/briansolomon/2012/03/29/2-billion-dodgers-sale-tops-list-ofmost-expensive-sports-team-purchases-ever/.

- Michael K. Ozanian and Kurt Badenhausen, “The Business of Baseball,” Forbes Magazine, April 16, 2008, http: http://www.forbes.com/2008/04/16/baseballteam-values-biz-sports-baseball08-cx_mo_kb_0416baseballintro.html. Note the remaining nineteen teams are shown on the NACVA website at http://www.nacva.com/examiner/14-SO-Charts.asp.

- Until recently, Forbes was the only public source of estimates for major league sports teams. They have been developing revenue, profit, and value estimates for over seventeen years. Numbers are as of Dec. 31, 2013.

- Mike Ozanian, “Baseball Team Values 2014 Led by New York Yankees at $2.5 Billion,” Forbes Magazine, March 26, 2014, http://www.forbes.com/sites/mikeozanian/2014/03/26/baseball-team-values-2014-led-by-newyork-yankees-at-2-5-billion/.

- Sources: Proprietary team sources.

- 6 Christina Settimi, “Baseball Scores 12 Billion in Baseball Deals,” Forbes Magazine, October 2, 2012, www.forbes.com.

- Bankruptcy Court For The Northern District Of Texas Fort Worth Division, Texas Rangers Baseball Partners, Chapter 11, Case No. 10-43400-DML.

- Source: Proprietary

- Source: Proprietary

Are There Really 2 NHLs?

This article was originally published in Valuation Viewpoint, October 2014. Mercer Capital is the leader in professional sports valuation. In an increasingly competitive professional, Mercer Capital’s capabilities in franchise valuation, divorce litigation, purchase price allocations, stadium issues, and legal consulting are unsurpassed. We have deep industry knowledge and experience and a deep bench of professionals ready to help. For more information, visit our Professional Sports Industry landing page.

When it comes to the four major league sports (NFL, MLB, NBA, NHL), the NBA and MLB have had less success in Canada vs. the USA, primarily due to demographics. With the exception of Toronto, most of the cities tend to be smaller and have fewer corporate headquarters relative to U.S. cities. Currently there is only one NBA and one MLB team in Canada, both in Toronto.

There is one major league sport, however, that is thriving in Canada, the National Hockey League (“NHL”). The NHL teams in Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Ottawa, Toronto and Montreal are doing very well. In fact, they’re doing much better on average than their U.S. counterpart cities that have much larger populations (i.e. Dallas and Atlanta which is now a former NHL city). So much so that one may say there are really two NHLs, the Canadian NHL and the U.S. NHL.

How can that be?

Let’s look at the estimated 2013 franchise values of the teams as published by Forbes magazine. Three of the seven Canadien teams are in the top four of league franchise values. The Toronto Maple Leafs are first at $1.2 billion, the Montreal Canadiens third at $775 million and the Vancouver Canucks fourth at $700 million. The NHL league average is $413 million. The remaining Canadian teams are valued as follows:

- (#11) Calgary Flames $420 million

- (#14) Edmonton Oilers $400 million

- (#15) Ottawa Senators $380 million

- (#16) Winnipeg Jets $340 million

Our home team, the Dallas Stars, comes in at $333 million and the Columbus Blue Jackets rank last at $175 million.

Now some interesting numbers: the seven Canadian teams feature values averaging $595 million, while the 23 American NHL teams average $358 million. That’s a little over half of the Canadian teams.

How can the New York Islanders, with a metropolitan statistical area (“MSA”) population of 19.9 million, be worth $195 million, while the Winnipeg Jets, with an MSA population of 0.7 million, are valued at $340 million? Additionally how can Vancouver, with a MSA population of 2.3 million, be valued at $700 million? The franchise value relationship with MSA population does not directly correlate. How can this be?

The answer is the popularity of hockey in Canada has no comparison to most U.S. cities. Hockey is the national sport of Canada. Kids grow up playing it, watching it and living it. That culture creates much greater revenue and profits for their teams. This can be demonstrated by analyzing the national television revenues and the local revenues of NHL teams.

NHL: National Television Revenues

The U.S. has a population of 319 million people vs. 35 million for Canada, yet the national TV rights for the NHL in Canada was recently won by Rogers Communications for $5.2 billion over 12 years, or an average of $433 million a year. This compares to the $2 billion, 10-year NBC U.S. deal which averages $200 million per year. In addition, 65% of the Canadian national TV rights will be shared with the 23 U.S. teams. It is interesting that a country with one-tenth the population gets about 2.2 times the national TV revenues compared to the U.S. and then has to share with the U.S. teams.

NHL: Local Revenues

Local TV rights are retained by the teams, as are other local revenues from suites, sponsorship and ticket revenues. Here again, the Canadian teams far outshine the U.S. teams. Forbes estimates the average NHL ticket prices in Canada for six out of the seven teams was $70 for non-premium tickets. Forbes estimated that small markets, Edmonton and Calgary, each had $1.6 million in annual ticket revenues. Compare that figure with the New York Rangers ticket revenue of $1.8 million, and that comparison is shocking (if that is not shocking to you, please compare populations of the three cities). Additionally, local television viewing shows the same type of comparisons as national TV viewing. Therefore, smaller Canadian markets like Vancouver will have multiples of local TV revenue when compared to a larger U.S. market, like Dallas.

Conclusion

In conclusion, after considering the numbers, it is hard to make a case for franchise value comparison between Canadian and U.S. NHL teams. Clearly, the economics indicate there are two different NHLs.

NBA Team Values: Three Ways Cuban and his Owner Bretheren are Cashing In

In a recent article Mark Cuban commented how media revenues will push National Basketball Association (“NBA”) valuations far higher than they are currently. “If we do this right, it’s not inconceivable that every NBA franchise will be worth more than $1 billion within ten years,” he was quoted as saying. While that observation could be on the money, it’s not the only engine that drives NBA team values. NBA franchises are unique properties that are often among the most attractive and reported upon assets in the US (and globally for that matter thanks to Mr. Prokhorov). The undergirding economics of these teams are complex and nuanced. When value drivers align, good things happen and value is unlocked. Like a flywheel with momentum, certain dynamics can push values upward quickly. However, the same dynamics can push the flywheel off its hinges, bringing values crashing down. It’s an exciting property that doesn’t always follow the path of conventional valuation theory, which might be a reason why a Maverick like Mark Cuban loves it so much.

NBA franchise values have recently gone in an upward direction as evidenced by the Sacramento Kings’ $534 million sale in January 2013. That’s quite a figure for the 27th ranked metropolitan statistical area (“MSA”) in the country. This transaction is especially fascinating in light of the Philadelphia 76ers (5th largest MSA) selling for only $280 million just 18 months earlier. What fuels such a vast difference? We explore three issues that contribute considerably to these variances – media rights, arena lease structure, and the NBA’s collective bargaining agreement (“CBA”). Some of these factors are more within an owner’s control than others, but all of them contribute to situational changes that valuations hinge upon. We’ll also explore the tale of two transactions: the 76ers and Kings, to see why and how these factors influence the purchase price.

Media Rights: The Quest for Live Content

It is important to note the majority of NBA team revenues come from local sources, (i.e. game day revenues and local media contracts). The most dynamic (and thus value changing) of these sources in the past few years has been local media rights. National media revenues in NBA are significant but are a much lower percentage of total revenues than the biggest league in North America, the NFL. According to Forbes, the 30 NBA teams collectively generated $628 million from local media last season (about $21 million average per team). In addition, national revenues from ESPN, ABC & TNT total $930 million per year and these deals expire in 2015-2016. It’s a relatively balanced mix compared to the other major leagues. NHL & MLB’s media revenues are more locally focused, while the NFL is nationally dominated.

Basketball’s popularity has grown in recent years. This, coupled with intense media competition for quality live content, has fueled increased media contracts in many markets at unprecedented levels (300% to 500%) over prior contracts.

Live sports programming has a relatively fixed supply and is experiencing increased demand from networks looking for content those viewers will watch live. This commands higher advertising dollars compared to content that is consumed over DVRs and online forms (Netflix, Hulu Plus, Amazon Prime, etc.). Content providers also covet the low production costs and favorable demographics of younger fans. These factors, among other variables, have helped fuel the rapid price increases for sports media rights.

Recently, new media rights contracts across all sports programming have soared to record high annual payout levels. The NHL signed two new TV deals in April 2011 which more than doubled the league’s previous annual payouts with an upfront payment of $142 million. Even the media rights for Wimbledon have seen an increase in the amount of suitors. The NBA’s current national deal expires in a couple of years (2016). Many people expect that the next deal’s value will at least double the current agreement. [Side note: In negotiations that date back to the 70’s ABA/NBA merger, two brothers – Ozzie and Daniel Silna, received a direct portion of the NBA’s national TV revenues – in perpetuity. That’s right…perpetuity. In January 2014 they agreed to a $500 million upfront payment from the NBA and a pathway to eventually buy them out completely. The old transaction has withstood litigation and it has been termed as ‘the greatest sports business deal of all time’]

At the local level, in 2011 the Los Angeles Lakers signed the richest television deal in the NBA which dwarfs other teams. The contract reportedly averages $200 million per year for 20 years. The upper tier NBA franchises historically have received $25 to $35 million annually. Some big market teams have expiring contracts in the next few years, such as the Mavericks. While bidding has not yet begun, it’s reasonable to expect Mr. Cuban and his Mavericks to anticipate a healthy bump in rights fees in the future assuming good counsel and creative structuring.

How did these factors translate to the Kings and 76ers? Even with substantial MSA differences, they were at opposite ends of the media spectrum. The Kings’ deal with CSN California expires after this season, which put ownership in strong position to negotiate a new deal at the time of the transaction. The 76ers signed a 20 year contract in 2009 with Comcast Sports Net, which was reported by Forbes to be “undervalued” from the 76ers perspective, reportedly paying the team less than $12 million the season prior to purchase. That’s quite a difference and it almost surely played a pertinent role the Kings’ and 76ers’ valuations.

Arena Lease and Structure: Slicing Up the Game Day Pie

In the NBA, game day and arena revenue typically make up the lion’s share of a franchise’s income. These revenue streams filter up from a multitude of sources. Aside from regular ticket sales there are club seats, suites, naming rights, parking, concessions, merchandise, and sponsorship revenue. In addition there are non-game revenues such as concerts, events and meetings. On the expense side there’s rent (fixed or variable), revenue sharing (or a hybrid arrangement), capital expenditures, maintenance, overhead allocation and more. All of these aspects are negotiable among the business, municipal, and legal teams involved.

Arena deal structures vary across the board. For example, the Detroit Pistons own The Palace at Auburn Hills while the Golden State Warriors are tenants at Oracle Arena (probably until 2017/2018 anyway). Most arena structures involve some form of public/private partnership. One common theme is public ownership, usually financed via local bonds, with the sports franchise as a tenant paying rent of some form. The chief aspect to consider for legal teams is how to structure agreements for the various revenue streams, expense and capital items.

Historically, some of the most negotiated aspects to the arena lease are how proceeds from certain items as defined by the CBA are allocated. For example, while players as a group receive a flat percentage of basketball related income (“BRI”), they receive reduced percentages of others, such as luxury suites and arena naming rights. This nuance represents an opportunity for team ownership to retain a larger portion of these revenues and legal teams to employ shrewd negotiating tactics. In addition, as the arenas age and significant maintenance costs are required, cost sharing between the public/private partnerships can become an issue. Lease structure also can make outright ownership of a stadium appear less attractive without a partner to share or bear costs.

Again as we examine the Kings and 76ers a contrasting picture emerges. Prior Kings’ ownership (the Maloofs) and the city could not reach an agreement on a new stadium lease after nearly a decade of negotiations. Initially there was a buying group that planned to move the team to Seattle, but then, new local ownership purchased the team (with substantial input from the NBA). This agreement included an agreement for a new $447 million stadium (the majority funded publicly) and a guarantee to keep the team in Sacramento. This new deal was reported to be more favorable to ownership and gives the franchise an opportunity to attract more fans and create refreshed revenue channels. The 76ers on the other hand had already been locked into a long term lease at less favorable terms that were more geared towards revenue sharing with Comcast. Again, the Kings’ new opportunity appears more attractive than the 76ers existing arrangement.

Collective Bargaining Agreement: Leveling the Playing Field

On December 8, 2011, after a 161 day lockout, the NBA and its player union reached a new collective bargaining agreement. This agreement brought about meaningful changes to the salary structures, luxury tax, BRI, and free agency (among other things). Although the CBA is not under direct control of a franchise owner, its impact on competiveness, team operational strategy and expense management is significant.

The changes were important for owners, who had reportedly lost over $300 million annually as a group in the three prior years to the negotiations. From a valuation perspective three items deserve focus: (i) length, (ii) BRI, and (iii) luxury tax provisions. Prior to the agreement, there was a great deal of uncertainty as to how negotiations would play out. Uncertainty infers risk and where there’s more risk, values usually fall. The 10 year agreement (with a 2017 opt-out) brings stability to both players and owners as to what operating structure they can plan for the near to intermediate term future. In addition, BRI revenue splits to the players were lowered from 57% of BRI to around 50% for most of the contract. This split brings cash flow relief (but not competitive relief) to owners across the league. Lastly, the luxury tax structure became much more punitive for big-spending owners, like Cuban. In fact, it economically functions similarly to a hard salary cap that the NFL and NHL employ. In light of this change, NBA franchises have committed an enormous amount of time and resources to understand and execute an appropriate competitive strategy. The luxury tax provisions even the competitive playing field for smaller market teams such as Sacramento and the Memphis Grizzlies (who sold for a reported $377 million in October 2012) and constrains the spending of larger market teams such as the Mavericks, Lakers or Knicks.

How did this facet play out with the Kings and 76ers? All one needs to know is that the 76ers were sold before the new CBA was agreed (Summer 2011) to and the Kings were sold after the CBA was in effect (January 2013). Timing, coupled with the Kings small market status, has an increasingly positive effect on them compared to the 76ers. Advantage: Kings.

Takeaway: NBA Boats Don’t Necessarily Need the Tide to Rise (or Fall)

NBA franchise values are on the rise. There is a buzz around the league that if there were teams on the market the price would be robust right now. The values are driven by a number of different factors (TV, arena rights, CBA), some that cannot be controlled by owners and their advisory teams, but others that can be. Don’t be fooled by market size. A value creation scenario can occur in almost any market. In one of the smallest markets in the country, Tom Benson paid more for the Hornets than Josh Harris’ group did for the 76ers. However, owner involvement, savvy counsel and careful negotiations are a must; because as some transactions have shown, there are no guarantees.

This article was originally published in The Texas Lawbook in March 2014.

2015 Bank M&A Recap

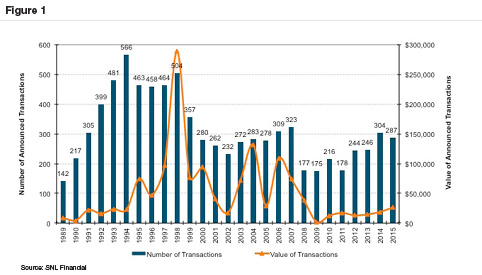

Statistics can be deceptive. The bank M&A market in 2015 could be described as steady, bereft of any blockbuster deals. According to SNL Financial 287 depositories (253 commercial banks and 34 thrifts) agreed to be acquired in 2015 compared to 304 in 2014 and 246 in 2013. Since 1990, the peak in M&A transactions occurred in 1994 (566) followed by 1998 (504). For those who do not remember, 1998 was the blockbuster year when NationsBank/Bank of America, Norwest/Wells Fargo, Bank One/First Chicago NBD and SunTrust Banks/Crestar Financial among others agreed to merge (Figure 1).

There has been a cumulative impact of M&A activity over the years. As of September 30, 2015, there were 6,270 insured depositories compared to about 18,000 institutions in 1985 when interstate banking laws were liberalized. M&A activity when measured by the number of transactions obviously has declined; however, that is not true on a relative basis. Since 1990, the number of institutions that agreed to be acquired in non-assisted deals ranged between 1.4% (1990) and 4.6% (1998) with an overall median of 3.2%. Last year was an active year by this measure, with 4.4% of the industry absorbed, as was 2013 (4.5%).

What accounts for the activity? The most important factors we see are (a) good asset quality; (b) currency strength for many publicly traded buyers; (c) very low borrowing costs; (d) excess capital among buyers; and (e) ongoing earnings pressure due to heightened regulatory costs and very low interest rates. Two of these factors were important during the 1990s. Asset quality dramatically improved following the 1990 recession while valuations of publicly traded banks trended higher through mid-1998 as M&A fever came to dominate investor psychology.

Today the majority of M&A activity involves sellers with $100 million to $1 billion of assets. According to the FDIC non-current loans and ORE for this group declined to 1.20% of assets as of September 30 from 1.58% in 2014. The most active subset of publicly traded banks that constitute acquirers is “small cap” banks. The SNL Small Cap U.S. Bank Index rose 9.2% during 2015 and finished the year trading for 17x trailing 12 month earnings. By way of comparison, SNL’s Large Cap U.S. Bank Index declined 1.3% and traded for 12x earnings. Strong acquisition currencies and few(er) problem assets of would-be sellers are a potent combination for deal making.

Earnings pressure due to both the low level of rates (vs. the shape of the yield curve) and post-crisis regulatory burdens are industry-wide issues. Small banks do not have any viable means to offset the pressure absent becoming an acquirer to gain efficiencies or elect to sell. Many chose the latter. The Fed may have nudged a few more boards to make the decision to sell by delaying the decision to raise short rates until December rather than June or September when the market expected it to do so. “Lift-off” and the attendant lift in NIMs may prove to be a non-starter if the Fed is on a path to a one-done rate hike cycle.

As shown in Figure 2, pricing in terms of the average price/tangible book multiple increased nominally to 142% in 2015 from 139% in 2014. The more notable improvement occurred in 2014 when compared to 2013 and 2012, which is not surprising given the sharp drop in NPAs during 2011-2013. The median P/E multiple was 24x, down from 28x in 2014 and comparable to 23x in 2013. The lower P/E multiple reflected the somewhat better earnings of sellers in which pricing was reported with a median ROA of 0.65% compared to 0.55% in 2014. Although the data is somewhat murky, we believe acquirers typically pay on the order of 10-13x core earnings plus fully-phased-in, after-tax expense savings.

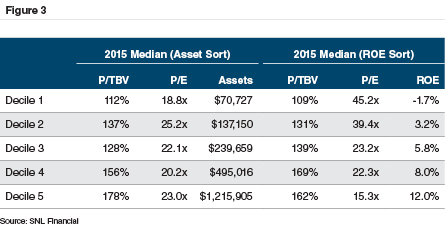

Figure 3 provides perspective on pricing based upon size and profitability as measured by LTM ROE. Not surprisingly, larger and more profitable companies obtained better pricing in terms of the P/TBV ratio; however, as profitability increases the P/E multiple tends to decline. That is not surprising because a higher earning bank should have fewer issues that depress current earnings.

The other notable development in 2015 was the return of non-SIFI large banks to the M&A market after largely being absent since the financial crisis as management and regulators sorted through the changes that the Dodd-Frank Act mandated. BB&T Corporation, which is among the very best acquirers, followed-up its 2014 acquisitions for Bank of Kentucky Financial Corp. and Susquehanna Bancshares with an agreement to acquire Pennsylvania-based National Penn Bancshares. The three transactions added about $30 billion of assets to an existing base of about $180 billion. Other notable deals included KeyCorp agreeing to acquire First Niagara ($39 billion) and Royal Bank of Canada agreeing to acquire City National Corporation ($32 billion). Also, M&T Bancorp was granted approval by the Federal Reserve to acquire Hudson City Bancorp ($44 billion) three years after announcing the transaction.

To get a sense as to how the world has changed, consider that the ten largest transactions in 2015 accounted for $17 billion of the $26 billion of transaction value compared to $9 billion of $19 billion in 2014. The amounts are miniscule compared to 1998 when the ten largest transactions accounted for $254 billion of $289 billion of announced deals that year.

Law firm Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz (“Wachtell”) noted that with the approval of several large deals this year there is more certainty to the regulatory approval process and there is no policy to impede bank mergers x-the SIFI banks. A key threshold for would-be sellers and would-be buyers from a decision process has been $10 billion of assets (and $50 billion) given enhanced regulatory oversight and debit card interchange fee limitation that applies for institutions over $10 billion. Wachtell cited the threshold as an important consideration for National Penn’s board in its decision to sell to BB&T.

There were a couple of other nuances to note. While not always true, publicly-traded buyers did not receive the same degree of “pop” in their share prices when a transaction was announced as was the case in 2012 and 2013. The pops were unusual because buyers’ share prices typically are flat to lower on the news of an announcement. Several years ago the market view was that buyers were acquiring “growth” in a no-growth environment and were likely acquiring banks whose asset quality problems would soon fade.

Also, the rebound in real estate values and resumption of pronounced migration in the U.S. to warmer climates facilitated a pick-up in M&A activity in states such as Georgia (11 deals) and the perennial land of opportunity and periodic busts—Florida (21). The recovery in the banking sector in once troubled Illinois was reflected in 25 transactions followed by 20 in California.

As 2016 gets underway, pronounced weakness in equity and corporate bond markets if sustained will cause deal activity to slow. Exchange ratios are hard to set when share prices are volatile, and boards of sellers have a hard time accepting a lower nominal price when the buyer’s shares have fallen. Debt financing that has been readily available may be tougher to obtain this year if the market remains unsettled.

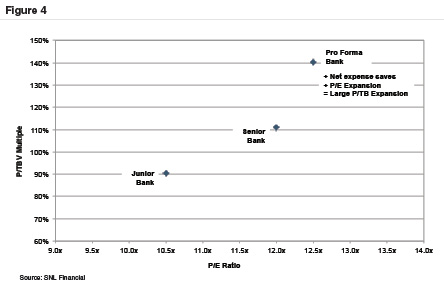

Whether selling or merging, we note for the surviving entity a key goal should be something akin to Figure 4 in which there is shared upside for both the acquirer’s and seller’s shareholders (assuming a merger structured as a share exchange). A well-structured and well-executed transaction can improve the pro forma bank’s profitability and growth prospects. If so, all shareholders may benefit not only from EPS accretion, but also multiple expansion.

We at Mercer Capital have over 30 years of experience of working with banks to assess transactions, ranging from valuation to issuing fairness opinions in addition to helping assess the strategic position (e.g., sell now vs. sell later). Please call if we can help your institution evaluate a significant corporate transaction.

Recent Trends in Agricultural Production Lending

Although farm income is projected to decline for a second consecutive year in 2015, farmers and the broader agricultural industry have had a great run since the Great Recession. The agricultural lending industry? Not so much.

Call it one of the age old conundrums of being in the business of lending money – those to whom you feel most comfortable lending are the least likely to need your services. Such has been the case for several years in the broader agricultural economy. Sure, there have been some farmers and ranchers willing to take advantage of low interest rates to increase leverage and enjoy the associated higher returns on equity and a larger fixed asset base with more profit potential. However, the painful deleveraging associated with the Great Recession left no sector of the economy untouched. Agricultural producers were no exception, with many eschewing debt in favor of fiscal conservatism.

This conservatism among most farmers is contrasted with foreign investors seeking U.S. assets and institutional investors who drove land prices to record level in many areas by 2013. The prices paid implied these investors were oblivious to generating an acceptable return. Elevated land prices have led to concerns among some that lenders could be exposed should land prices fall sharply with a secondary impact on production-related collateral values in a replay of the 1980s bust in the farm sector following the inflation and borrowing binge that occurred during the 1970s.

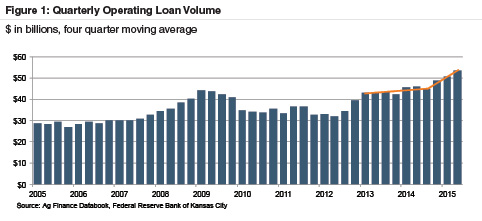

As for production-related lending, record yields and crop prices left many producers so flush with cash that borrowing needs declined. Data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City reveals a steadily declining trend in operating loan volumes at commercial banks over the 2009 to 2012 period (Figure 1). The second half of 2012 showed a rapid rise in loan volumes, but since then agricultural production loans have grown at a relatively slow pace – until recently, that is.

Volume Growth Picks Up Steam

A number of factors have finally reversed course, leading to a notable uptick in demand for financing and an expectation that ag production loan demand will remain strong in the near- term. While real estate agriculture loans also have increased, lending dollar volume in that area has been influenced by the substantial increase in farmland values in recent years. The discussion which follows focuses on production, or operating, lending.

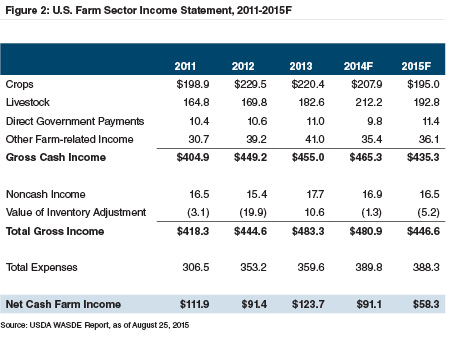

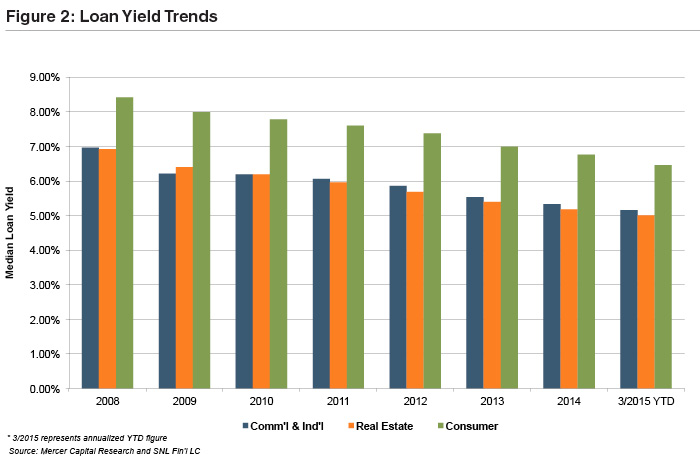

Several years of record crop yields and high commodity prices left farmers and ranchers with little need for operating loans. However, crop receipts are expected to decline by approximately 6% in 2015 and livestock receipts are expected to decline 9%. These declines will be modestly offset by an increase in direct government payments and other income. However, input expenses should remain stable, primarily reflecting higher costs for livestock purchases and labor offset by lower energy costs, leading to an expected 36% decline in net farm income. This decline comes on the heels of a 26% decline in 2014 (Figure 2).

Throughout 2014 producers had the luxury of strong balance sheets, allowing them to avoid significant operating debt despite the downturn in net income for that year. However, during 2015 the cash cushions built up during the commodity boom will begin to be depleted, leaving many producers with little choice but to finance short-term capital investment and input costs with borrowings.

Rates Hold Steady – For Now

The average effective interest rate on non-real estate bank loans to farmers declined from 5.6% in 2008 to 3.8% in 2014, but has shown two consecutive quarter over quarter increases (albeit modest) in the first half of 2015 and measured 4.1% in second quarter 2015. One possible explanation for this slight uptick is that as demand has picked up banks have regained the smallest amount of pricing power. Alternatively, it may be the case that the average borrower credit profile has deteriorated slightly as the industry comes off its highs from the recent commodity pricing boom.

Despite the low rates, ag production loans can be very attractive from an interest rate risk standpoint, as most of the loans renew annually allowing for more rapid adjustment when rates (finally) begin to rise. That said, oftentimes collateral used for non-real estate agricultural loans is less desirable, thus increasing the risk of the loan if it were to fail.

Producers Lock in Fixed Rates

There is an argument to be made that all of the factors affecting loan volume mentioned above are just noise, and producers are simply doing what mainstream America has been doing with residential mortgages for years – locking in these once-in-a-lifetime rates while they still can. The share of floating rate loans made by banks for non-real estate agricultural purposes fell to at least a 15-year low (60%) in the first quarter of 2015. Although it increased to 70.8% in the second quarter, that level remains well below the average exhibited since 2000.

Fixed rate loans are most commonly used for non-feeder livestock production and machinery and equipment, while floating rate loans are more common for shorter-term financing used for feeder livestock (typically sold to a feedlot within one year of age) and current operating and production expenses (including crop production).

Alternative Sources of Lending

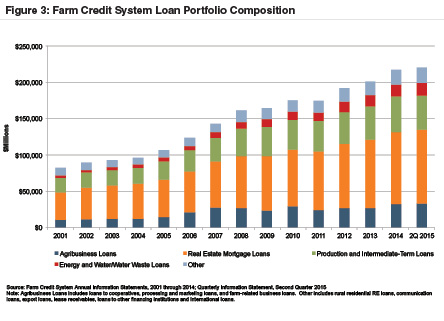

The amount of debt supporting the U.S. agricultural system is vast, and commercial banks are by no means the only player in town. The Farm Credit System (FCS), for example, funds approximately 39% of all U.S. farm business debt (according to the USDA) and commercial banks must compete with farm credit system banks for all types of agriculture and in all 50 states. While Call Report data compiled by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City shows rapid recent growth in non-real estate ag lending at commercial banks, financial data from FCS paints a slightly different picture.

Figure 3 shows steady total FCS loan growth since 2001. However, loan growth in the first half of 2015 was nearly flat, and production and intermediate term loans actually declined relative to year-end 2014. FCS states this decline was driven by borrowers’ tax planning strategies at the end of 2014, resulting in significant repayments in early 2015, as well as a high level of seasonal pay-downs in the first quarter. It’s difficult to draw the conclusion, however, that this data indicates a shift in market share away from FCS toward commercial banks, given classification, measurement and timing differences. It’s worth noting that FCS relies primarily on the public debt markets for its balance sheet funding and these costs increased modestly in the first half of 2015 relative to the same period in 2014.

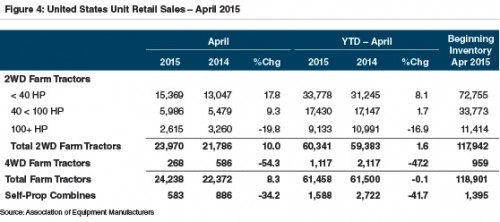

Another source of credit for the agricultural industry is financing provided by heavy equipment dealers and manufacturers. Equipment loan volume can be influenced by commodity cycles somewhat differently than for other operating loans. Producers generally prefer to invest in new equipment when times are good and net incomes are strong, electing to postpone larger capital purchases and make do with aging equipment in times of falling incomes. This effect has played out in the first part of 2015, with rather significant sales declines in what is normally an active period of highly seasonal buying patterns (Figure 4).

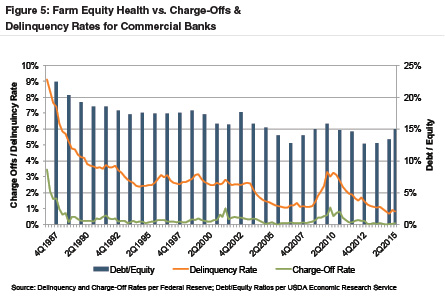

Implications for Asset Quality

Since peaking in late 2009, delinquency and charge-off rates on ag production loans held by commercial banks have fallen consistently and dramatically, and for second quarter 2015 measured 0.81% and 0.09% (seasonally adjusted), respectively. Asset quality data from FCS exhibits a similar trend. As shown in Figure 5, delinquencies and charge-offs tend to be closely correlated with the health of farm balance sheets, which is not surprising.

We note an interesting trend since the end of 2012 in which this relationship appears to have broken down. Farm debt to equity ratios are increasing, while delinquencies and charge-offs continue to decline. Is this a harbinger of things to come? It’s probably too soon to tell, as the agriculture industry is highly susceptible to completely unpredictable events, such as weather patterns, and the health of the overall global economy (also not an easy prediction these days). One thing is certain, the trend is not sustainable indefinitely.

Another issue with the comparability of recent trends to previous points in the long-term historical agriculture cycle is the impact that the dramatic increase in land values has had on farm equity since 2009. A portion of the rise in debt to equity ratios in recent periods is not due to an increase in debt, but rather recent declines in land values (falling asset values will increase debt/equity ratios, all else equal). If land values continue to decline from their historical highs (which most reliable sources predict), and farm debt continues to increase (which all of the factors discussed above would indicate) then leverage ratios will be further strained in the coming quarters and years. Current charge-off rates are de minimis to the point where an increase in asset quality issues related to agricultural production loans will be easily absorbed by all but the most concentrated ag lenders. That said, it bears watching to see if these trends become more sustained and have deeper implications for both agricultural lending and the broader agricultural economy.

August Market Performance & Augustus Caesar

In contemplating August’s market activity, our thoughts drifted to Roman times. In 45 B.C., the Roman Senate honored Julius Caesar by placing his name on the month then known, somewhat drably, as Quintilis. Later, the Senate determined that Augustus Caesar deserved similar recognition, placing his name on the month after July. But this created an immediate issue in the pecking order of Roman rulers – up until then, months alternated between having 30 and 31 days. With July having 31 days, poor Augustus’ stature was diminished by placing his name on a month having only 30 days. To rectify this injustice, the Senate decreed that August also have 31 days, accomplished by borrowing a day from February and shifting other months such that September only had 30 days (to avoid having three consecutive 31-day months).

We provide this historical interlude to illustrate that, while July and August now are equivalent in terms of the number of days, the market environment in these two months during 2015 bore few similarities. In August, volatility returned, commodity prices sank, and expectations of Federal Reserve interest rate action in September diminished.

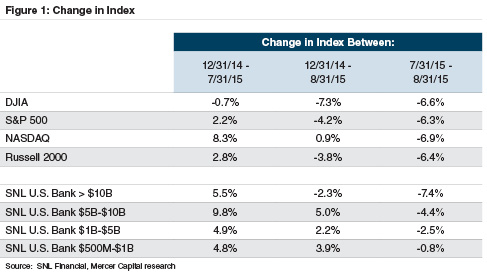

Most broad stock market indices declined between 6% and 7% in August, taking the indices generally to negative territory year-to-date in 2015. As indicated in Figure 1, except for the largest banks, publicly-traded banks generally outperformed the broader market, both year-to-date in 2015 and in August specifically.

For the year, banks benefited from several factors. First, investors appear to expect that rising interest rates will, if not enhance banks’ earnings, at least prove to be a neutral factor. Other sectors of the market, though, may be less fortunate, as companies face higher interest payments or other adverse effects of higher interest rates. Second, banks generally reported steady growth in earnings per share, as assisted by a benign credit environment.