Bridging Valuation Gaps With Options

How Option Pricing Can Be Used to Understand the Future Potential of Assets Most Affected by Low Prices, PUDs and Unproven Reserves

Due to the precipitous drop in oil prices in 2020, oil E&P companies in the U.S. have struggled to pay their debts, and in many cases already have had to file for bankruptcy. In this post, we re-examine how option pricing, a sophisticated valuation technique, can be used to understand the future potential of the assets most affected by low prices, PUDs and unproven reserves. Whether companies are looking to sell these reserves to improve their cash balance, or are trying to generate reorganization cash flow projections during a Chapter 11 restructuring, understanding how to value PUDs and unproven reserves is crucial to survival in a down market.

The Struggle: Valuation in Distressed Markets

The petroleum industry was one of the first major industries to widely adopt the discounted cash flow (DCF) method to value assets and projects—particularly oil and gas reserves. These techniques are generally accepted and understood in oil and gas circles to provide reasonable and meaningful appraisals of hydrocarbon reserves. When market, operational, or geological uncertainties become challenging, such as in today’s low price environment, the DCF can break down in light of marketplace realities and “gaps” in perceived values can appear.

The DCF can break down in light of marketplace realities and “gaps” in perceived values can appear.

While DCF techniques are generally reliable for proven developed reserves (PDPs), they do not always capture the uncertainties and opportunities associated with the proven undeveloped reserves (PUDs) and particularly are not representative of the less certain upside of possible and probable (P2 & P3) categories. The DCF’s use of present value mathematics deters investment at low ends of pricing cycles. The reality of the marketplace, however, is often not so clear; sometimes it can be downright murky.

In the past, sophisticated acquirers accounted for PUDs upside and uncertainty by reducing expected returns from an industry weighted average cost of capital (WACC) or applying a judgmental reserve adjustments factor (RAF) to downward adjust reserves for risk. These techniques effectively increased the otherwise negative DCF value for an asset or project’s upside associated with the PUDs and unproven reserves.

At times, market conditions can require buyers and sellers to consider methods used to evaluate and price an asset differently than in the past. In our opinion, such a time currently exists in the pricing cycle of oil reserves, in particular to PUDs and unproven reserves. In light of oil’s low price environment, coupled with the future price deck, many, if not most, PUDs appear to have a negative DCF value.

What does this mean for the E&P companies looking to reorganize under a Chapter 11 Bankruptcy? There are five key concepts for management teams and their advisors to be familiar with to understand how reserve valuation impacts Chapter 11 reorganization.

- Liquidation vs. Reorganization. The proposed reorganization plan must establish a “reorganization value” that provides superior outcomes for shareholders relative to a Chapter 7 liquidation proceeding.

- Liquidation Value. This premise of value assumes the sale of all of the company’s assets within a short period of time. Different types of assets might be assigned different levels of discounts (or haircuts) based upon their ease of disposal.

- Reorganization Value. As noted in ASC 852, Reorganizations, reorganization value “generally approximates the fair value of the entity before considering liabilities and approximates the amount a willing buyer would pay for the assets of the entity immediately after the restructuring.” Reorganization values are typically based on DCF analyses.

- Cash-Flow Test. A cash-flow test examines the viability of a reorganization plan, and should be performed in order to determine the solvency of future operations. In practice, this test involves projecting future payments to creditors and other cash flow requirements including investments in working capital and capital expenditures.

- Fresh-Start Accounting. Upon emergence from bankruptcy, fresh-start accounting may be required to allocate a portion of the reorganization value to specific identifiable intangible assets. Fair value measurement of these assets typically requires use of the multi-period excess earnings method or other techniques often used in purchase price allocations following a business combination.

If recent market transactions are utilized to establish a liquidation value, then it stands to reason that very little, if any, value will be given to the PUD reserves. For a company trying to avoid liquidation in a distressed market where sale prices do not indicate the true value, there may still be a way to demonstrate significant value if reserves are retained in reorganization. However, that reorganization value has typically been based on a DCF. It is possible that the DCF may capture significant value in PUD reserves because in reorganization debt levels are adjusted. When debt levels are adjusted the cash flow PUD reserves need to generate to be viable is much lower. This will provide two significant benefits: more time and possibly more cash. More time may allow global and regional oil and gas prices to increase while the additional cash flow from lower interest payments may allow investment in future PUD wells.

Unfortunately, it is still the case that the present value calculation is strongly tied to current market conditions, and thus even for companies with reasonable leverage, many PUD and unproven reserves show negative cash flow. The presence of some sizable transactions made without significant PDPs shows that there are buyers who disagree with this assessment and see value in these reserves. The issue is demonstrating that value in either a sale or bankruptcy scenario. An option pricing model is one solution that could account for the value of the increased time provided by restructuring the debt.

Option Pricing Providing A Potential Solution

One of the primary challenges for industry participants when valuing and pricing oil and gas reserves is addressing PUDs and unproven reserves. As previously discussed, if one relied solely on the market approach many of these unproven reserves would be deemed worthless. Why then, and under what circumstances, might the unproven reserves have significant value?

The answer lies within the optionality of a property’s future DCF values. In particular, if the acquirer has a long time to drill, one of potentially multiple forces come into play: either the PUDs potential for development can be altered by fluctuations in the price outlook for a resource, or, as seen with the rise of hydraulic fracturing, drilling technology can change driving significant increases in the DCF value of the unproven reserves.

This optionality premium or valuation increment is typically most pronounced in unconventional resource or when the PUDs and unproven reserves are held by production. These types of reserves do not require investment within a fixed shorter and/or contractual timeframe.

Current Pricing Environment:

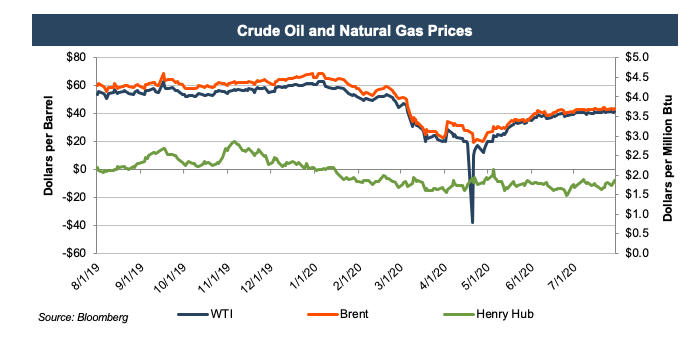

As oil prices have dropped and temporarily stabilized around $40 PUD values may drop precipitously.

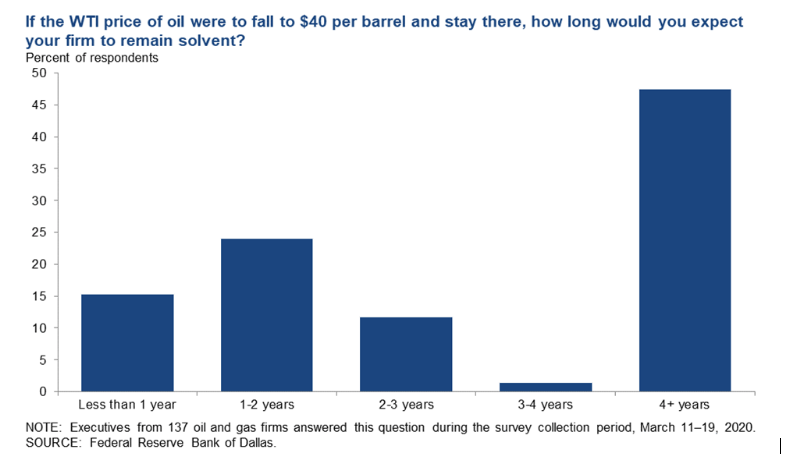

After the last recession, some PUDs faced a similar, yet more modest, decline in prices. In fact, nearly half the companies surveyed this spring by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas reported only being able to be solvent for 2-3 years at the most under these values. We have already seen some declare bankruptcy.

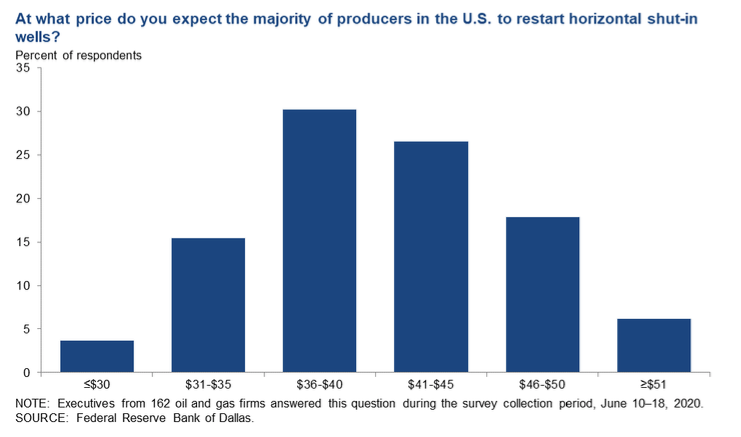

Valuation would be made easier if we could determine when oil prices would rise again. Valuations vary as to producers’ sensitivity to this price. The Dallas Fed’s latest survey suggests that $40 is about the tipping point to restart shut-in wells, but not necessarily to drill new ones:

Experienced dealmakers realize that the NYMEX future projections amount to informed speculation by analysts and economists many times vary widely from actual results. So what actions do acquirers take when values are out of the money in terms of drilling economic wells? Why do acquirers still pay for the non-producing and seemingly unprofitable acreage? In many cases, they are following a real option conceptual framework.

Real Options: Valuation Framework

PUDs are typically valued using the same DCF model as proven producing reserves after adding in an estimate for the capital costs (capital expenditures) to drill. Then the pricing level is adjusted for the incremental risk and the uncertainty of drilling “success,” i.e., commercial volumes, life and risk of excessive water volumes, etc. This incremental risk could be accounted for with either a higher discount rate in the DCF, a RAF, or a haircut. Historically, in a similar oil price environment, as we face today, a raw DCF would suggest little or no value for the PUDs or unproven reserves.

An option pricing model can guide a prospective acquirer or valuation expert to the appropriate segment of market pricing for undeveloped acreage.

In practice, undeveloped acreage ownership functions as an option for reserve owners; they can hold the asset and wait until the market improves to start production. Therefore an option pricing model can be a realistic way to guide a prospective acquirer or valuation expert to the appropriate segment of market pricing for undeveloped acreage. This is especially true at the bottom of the historic pricing range occurring for the natural gas commodity currently. This technique is not a new concept as several papers have been written on this premise. Articles on this subject were written as far back as 1988 or perhaps further, and some have been presented at international seminars.

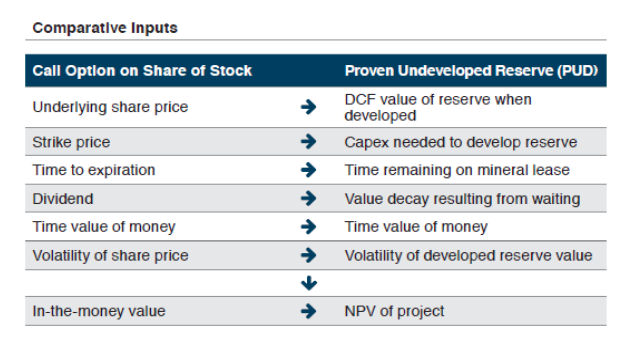

The PUD and unproved valuation model is typically seen as an adaptation of the Black Scholes option model. It is most accurate and useful when the owners of the PUDs have the opportunity, but not the requirement, to drill the PUD and unproven wells and the time periods are long, (i.e. five to 10 years). The value of the PUDs thus includes both a DCF value, if applicable, plus the optionality of the upside driven by potentially higher future commodity prices and other factors. The comparative inputs, viewed as a real option, are shown in the table below.

When these inputs are used in an option pricing model the resulting value of the PUDs reflects the unpredictable nature of the oil and gas market. This application of option modeling becomes most relevant near the bottom of historic cycles for a commodity. In a high oil price environment, adding this consideration to a DCF will have little impact as development is scheduled for the near future and the chances for future fluctuations have little impact on the timing of cash flows. At low points, on the other hand, PUDs and unproved reserves may not generate positive returns and thus will not be exploited immediately. If the right to drill can be postponed for an extended period of time, (i.e. five to ten years), those reserves still have value based on the likelihood they will become positive investments when the market shifts at some point in the future. In the language of options, the time value of the currently out-of-the-money drilling opportunities can have significant worth. This worth is not strictly theoretical either, or only applicable to reorganization negotiations. Market transactions with little or no proven producing reserves have demonstrated significant value attributable to non-producing reserves, demonstrating the recognition by some buyers of this optionality upside.

All that said, there are some challenges and dangers in applying the options model to reserves such as observable markets, risk quantification, assumption sensitivity, service and drilling availability, and time to expiration to name several.

Utilization of the modified option theory is not in the conventional vocabulary of many oil patch dealmakers, but the concept is considered among E&P executives as well during transactions in non-distressed markets. If the right to drill can be postponed for an extended period of time, (i.e. five to ten years), the time value of the out-of-the-money drilling opportunities can have significant worth in the marketplace. Careful application is important, but given today’s conditions, the benefit can outweigh the challenges.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights