Chasing Waterfalls: How Volatile Equity Structures Are Changing Returns

Oil and gas asset values have experienced tremendous volatility over the past year. They have almost returned to where they started in 2020. However, most investors have experienced that unpredictable possibility differently than their assets have since they are not actually participating directly in assets. I am not just talking about debt leverage effects here either. Instead, people are investing in an entity that, in turn, owns and operates a group of assets. These equity and entity structures can change volatility exposure depending on how it is constructed. This includes what is known by multiple names, but generally called an equity distribution waterfall. Investopedia defines a distribution waterfall as “a way to allocate investment returns or capital gains among participants of a group or pooled investment.” The operative word there is “allocate.”

Distribution waterfalls are mechanisms to allocate not only profit but also risk. Frequently found in joint venture arrangements and other financing structures such as DrillCos, distribution waterfalls have become a popular arrangement in recent years. The possibilities of an equity allocation are technically and practically endless yet generally negotiable. However, they often follow a typical framework. First, there is usually language in agreements for return of capital provisions, often followed by a preferred return provision. Lastly, residual returns are then usually subject to some form of payout split between investors. Some investors provide capital at the outset of the project which is a key economic factor for the distribution waterfall. Other investors provide non-capital contributions such as management expertise, technology, or assets in-kind. These different contributions can be beneficial to the entity by improving capital efficiency, synergizing expertise, creating optionality in varying respects or accelerating development timing.

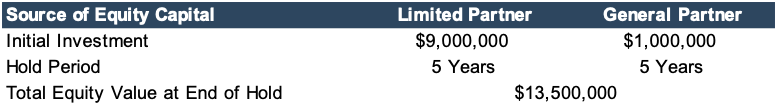

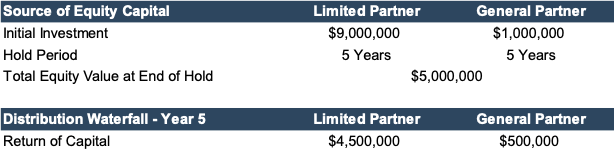

Things get interesting when contributions convert into distributions from a sale or liquidity event. Each investor can have different return profiles depending on the waterfall structure. Incentives can vary too. Sometimes they can be aligned, other times not so much. Take a hypothetical and simplified example; An upstream partnership is formed between an investor with mostly capital and a knowledgeable management team. $10 million of capital is provided to fund the assets in a domestic play with $9 million contributed by the investor and $1 million by the management team. No debt is procured. Each investor agrees that the distribution waterfall will begin with a return of each investor’s capital pro-rata, then secondly earn a 7% preferred return, lastly, residual cash flow is split 70/30. The management team runs the business and is reasonably compensated during this time. In five years, they sell the assets for $13.5 million.

The returns for the partners might look something like this:

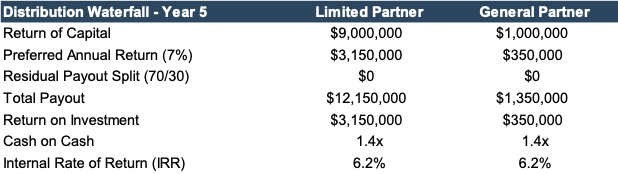

At first glance, this appears pretty simple. The payout made it only through the first two tiers of the waterfall with no residual cash flow to split in the 70/30 tranche. Everyone makes out the same. However, look at what happens when the total equity returns notch up to say $20 million in that same five-year period in this structure:

Both investors benefit in this scenario, but now the management team (general partner) has much higher relative return metrics relative to its original investment. In fact, they’ve more than doubled the limited partners’ returns from an IRR perspective and had over one turn better from a cash-on-cash perspective. That is great, however, this example assumes strong returns. That has not been the reality for most oil and gas ventures in the past year. What happens when asset values go down?

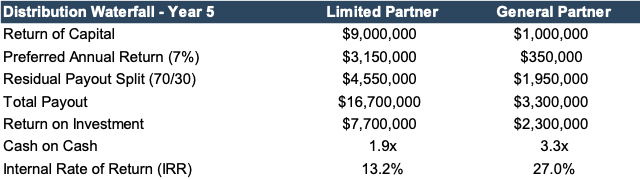

First, holding periods are sometimes extended if they can be to attempt to ride out the storm. In addition, further investments, and capital expenditures typically get trimmed, which can conserve cash but this can also generate strain on business plans, growth and holding periods leading to disagreements between management and investors on which path to take. Take the same example and assume a $5 million total return pot:

The limited partner in this example has lost 9x as much as the general partner management team because they had that much more to lose. Now, most parties prefer not to absorb that type of loss so what can also happen is the parties can extent holding periods in the hope that the time value optionality can prove fruitful to higher asset values later down the line. This can work, but not always.

The math is relatively straightforward in a liquidity event. But what about transactions that occur prior to a liquidity event? How do you account for the different payoff structures for components of the capital stock?

This is increasingly relevant as liquidity events have been deferred considering market conditions, and management teams are having difficult conversations with sponsors as portfolio companies are being consolidated (often referred to as “SmashCos”). NGP did this last year with some of its portfolio companies. Quantum Energy Partners did this for two of its Haynesville Midstream companies as well.

This brings up a delicate issue of how to re-allocate management’s equity ownership. The payoff structure of the waterfall is critical, as the value of a capital component does not necessarily equal its value under a liquidation scenario today. Just like stock options, certain capital components have optionality that results in incremental value over what is implied by the company’s current value. I have dealt with these option pricing models and scenario analyses, and sometimes they can reflect significant value beyond what a simple waterfall allocation might imply.

What is clear is that returns for the same asset can diverge quickly among different equity classes can end up being dramatically different over the course of an investment. Therefore, how they are set up can heavily influence the sometimes-delicate dance between equity holders. When asset values are high, then tensions among investors tend to ease, but in environments such as what we have seen recently, it can exacerbate them too.

Originally appeared on Forbes.com on March 10, 2021.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights