Oil Frackers Are Breaking Records Again – In Bankruptcy Court

This year has beaten down America’s oil producers. It started bad, with the Russian-Saudi battle for market share, then cascaded into terrible as the COVID pandemic gutted petroleum demand and sent oil prices down to an unheard of -$38 (negative!) per barrel.

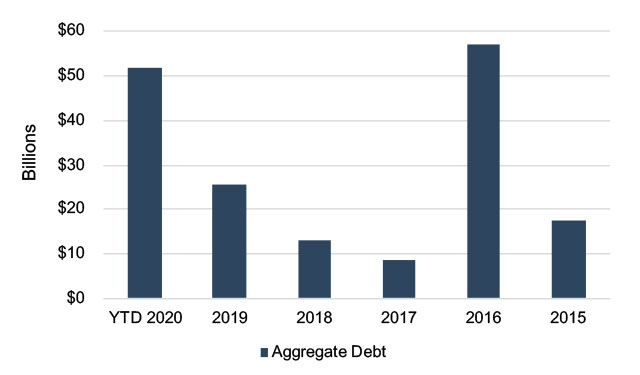

Those with the weakest hands have taken shelter in bankruptcy court, where it has been a busy six months. With the announcement of offshore producer Arena Energy’s bankruptcy late last week the count of North American bankruptcy filings for producers stood at 36 (31 of those have been in the second and third quarter so far this year). In terms of aggregate debt, the industry is near $53 billion for 2020 so far. That puts the upstream segment on the precipice of having the most debt dollars exposed to bankruptcy protection in U.S. history and we still have four months to go.

Some industry insiders are hearing that around 60-70 additional producers may file before year-end, meaning that a wave of companies are on this precipice. If that is the case, then Chapter 11 records will be left in the dust very shortly. That appears to be a monumental shift for six months of depressed prices, but it is important to remember that at around $50 per barrel (where oil had been most of the year prior) some upstream producers are barely breaking even. So when prices dropped even 15-20%, there wasn’t much margin left to work with.

As the industry heads down this road there will be some differences this time around compared to the surge in 2016, but with familiar signposts as well.

What’s Different This Time?

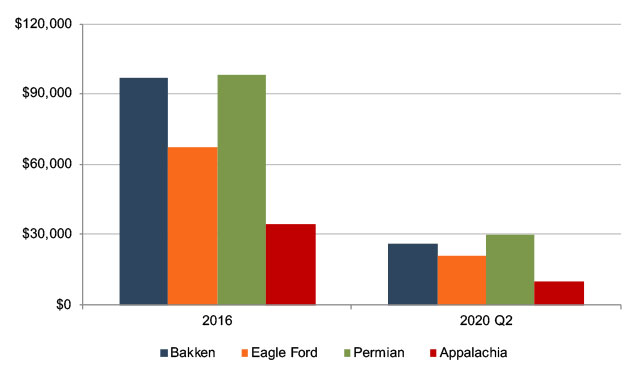

In 2016 a lot was different as far as the maturity and costs of drilling in the U.S. The Permian Basin was still getting its bearings on horizontal drilling in its bountiful stacked geologic formations in the Delaware and Midland sub-basins. Optimism and asset values were higher also as supply and demand balances were flipped in the U.S. at the time. While prices for 2016 averaged $43 per barrel, which is surprisingly close to today’s WTI prices of $42, asset values were far different and future drilling inventory (otherwise known as acreage) is currently valued significantly lower. The chart below gives us a glimpse of that.

Rig counts and production declines are a hot topic right now as rigs and production are becoming scarcer items. This is different from last time because a higher percentage of U.S. production is tied to horizontal shale wells which decline much faster than conventional wells. According to the latest Dallas Fed Energy Survey, 82% of respondents shut-in or curtailed production in the second quarter 2020. Most of those producers expect minor or even significant costs to put those wells back online. This devalues reserves and limits recoveries for unsecured creditors. In contrast, few if any were shutting in wells in 2016.

Another difference may be in how Chapter 11 reorganization plans consider future drilling plans and commitments. Let us not forget that an exploration and production company’s primary assets are essentially two things: (i) existing production and (ii) a drilling plan for future production. In the past, companies could effectively drill their way out of bankruptcy to generate cash flow, but as we’ve shown before, that may not be an option for some filers at $42 per barrel. Others that have hedged their production may have more latitude. That is a case by case situation. Drilling commitments and even force majeure are sometimes a significant negotiating point in bankruptcy cases.

What’s Not Different This Time?

For starters, this is some producers’ second or even third time that they have been in a restructuring situation in the past few years. This is sometimes known as the proverbial “Chapter 22” bankruptcy. Chaparral is one of those companies. In fact, Chaparral is an example of what else might not be different this time around –equitizing debt. Chaparral announced last week it will be equitizing all $300 million of its unsecured debt. Whiting’s bankruptcy will do this as well as their unsecured holders are estimated to recover around 39% of $2.6 billion in claims, but will end up owning 97% of the new company going forward, leaving 3% for the existing shareholders.

Speaking of unsecured debt, the magnitude of unsecured debt will set records. However, the mix of secured vs. unsecured debt, overall, is similar to 2016. Asset values on the other hand are in different places, particularly PUD’s. This creates some uncertainty as to exactly where in the debt stack that creditors may recover their capital or otherwise must restructure their interest, often referred to by insiders as the “fulcrum security.” In a Chapter 11 bankruptcy scenario, there is typically a tier of creditors that is only partially “in the money.” For example, if a debtor’s secured debt will be paid in full, but unsecured debt will receive say 20 cents on the dollar, the unsecured debt is what is known as the fulcrum security. This could also change during the bankruptcy especially if commodity prices change during the process and before plans of reorganization are approved. As challenging as this year has been so far, it is far from over and there may be a glimmer of hope that prices could rise before the end of the year.

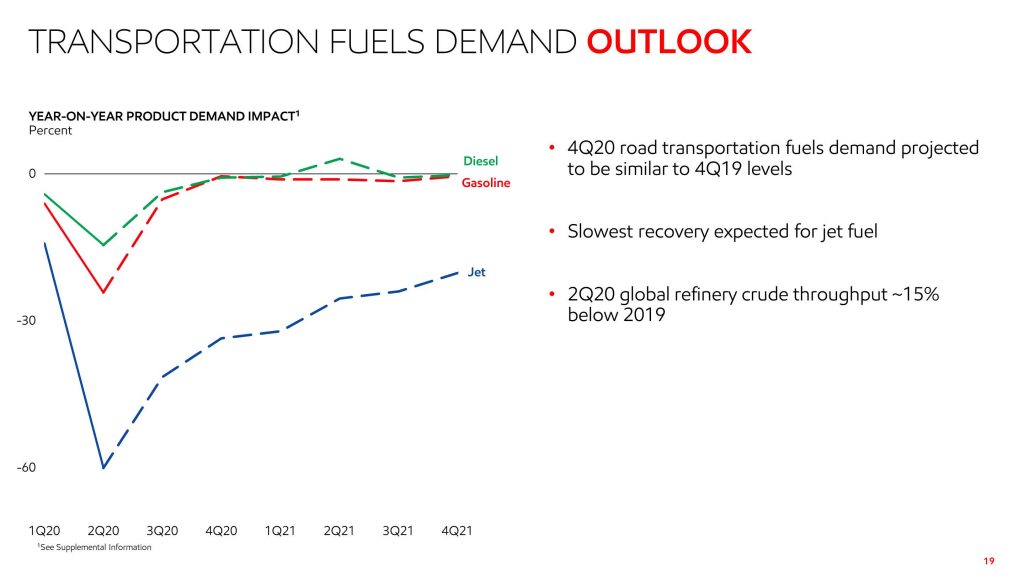

There are some bullish signs for oil. Drawdowns on inventories exceeding projections and have been coming down since mid-July. They now stand at levels similar to where they were in early April and are much closer to equilibrium than thought even 45 days ago. Fuel demand (except for jet fuel) is likely to recover before the end of the year, thus bringing upward pressure on prices according to ExxonMobil’s (XOM) latest investor presentation.

If this happens, it will improve creditor recoveries, and lubricate gears of the bankruptcy process. It would also bring relief to those who are not planning to file and are looking to weather this year’s storm. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that even a precipitous rise in prices could stop this year from breaking bankruptcy records. That is the unfortunate reality that makes 2020 a frustrating year for many.

Originally appeared on Forbes.com on August 25, 2020.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights