Appalachian Gas Valuations: The Bad, The Ugly, (And The Good)

Eli Wallach, Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef meet at the graveyard hiding place of the missing cashbox and each claims the money for himself in a scene from the film 'The Good, The Bad And The Ugly', 1966 | Getty Images

U.S. dry gas consumption will finish at an all-time high of 84.3 Bcf per day in 2019 and that figure will continue to grow into 2020. However, if gas investors are celebrating, no one knows where the party is. In reality, the investing atmosphere is gloomy with commodity prices consistently below $3.00 per MMcf on the NYMEX and even lower in some locations. The valuation environment is dispiriting for many investors in Appalachia. It doesn’t take long to get buried in a cavalcade of adverse indicators, corporate overhauls, depressed EBITDA multiples and state sized swaths of uneconomic acreage. Data suggests some producers could spend the foreseeable future languishing in shareholder jail or bankruptcy court.

How can economics get this jilted in arguably the largest gas field in the world? Perhaps it’s better to wonder why, at this point, would anyone even believe the dry gas investment premise at all? These are fair questions that investors and the broader stock market are asking themselves. Interestingly, there may be fair answers to them that, when analyzed closely, might chart a tough, disciplined course and perhaps eventually even position the Marcellus and Utica to be a globally superior gas field.

The Bad

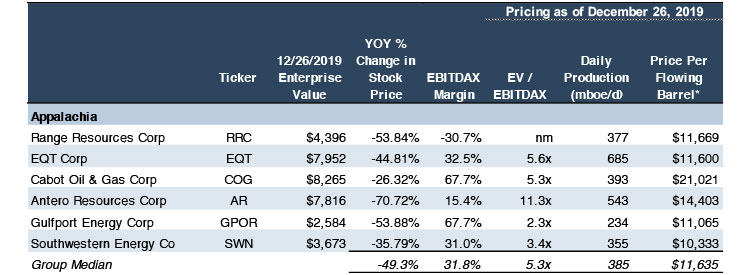

There’s no question that valuations are floundering at relative historic lows. Mercer Capital’s group of public Appalachian gas producers has dropped approximately 50% since last year. It’s the largest collective decline of any other publicly traded U.S. basin group. Of the publicly traded Appalachian-based gas producers, some are trading at the bottom of EBITDA multiple ranges, and nearly all trade at the bottom from a price per flowing barrel metric.

Source: Bloomberg

Transaction activity has been quiet as equity markets are closed and management teams are concerned with stewardship of their existing asset base. Deals that did close were production-oriented; some transacting at higher expected rates of return compared to historical norms (15% or even 20% rates of return).

It’s notable to point out that gas prices haven’t fallen nearly by the magnitude that stock prices have. So, what is happening to create such an investor flight? Consider recent developments.

Corporate Wrangling

Trials are front and center for independent producers. They have been pronounced at Gulfport and EQT, where management and shareholders engaged in some tumultuous struggles this year. Gulfport had board turnover and suspended a share repurchase program that it had initiated only earlier this year (in order to switch to a debt buyback program at a discount). At EQT, corporate governance has also been volatile. Toby and Derek Rice, whose eponymous company merged with EQT in November 2017, waged a successful proxy battle this year, proposing a business plan in September which included a 23% reduction in employees alongside a logistical and strategic overhaul of its drilling plan.

Throwing In A Major Towel

Trouble in Appalachia is not confined to the independents. Chevron recently announced a $10 – $11 billion write-down. More than half of its impairment is attributable to its Marcellus/Utica assets. Chevron’s large position and presence in the region is now mulling an exit from the play.

Cash Flow Challenges

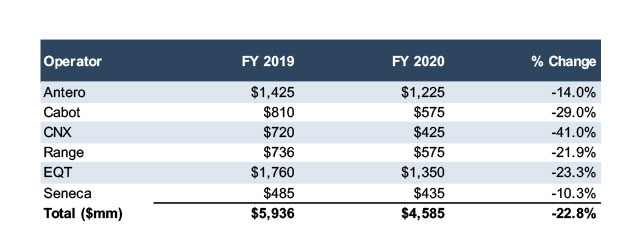

Due in part to the lack of available capital, early projections show capex reductions of 23% in 2020.

Source: Shale Experts

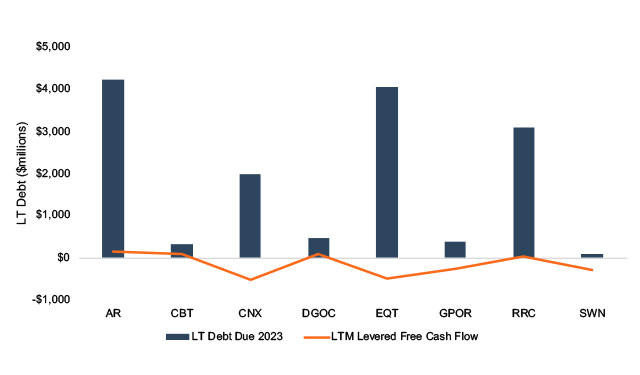

This strategy cuts both ways. It can conserve cash in the short-term to allocate towards debt repayment or share buybacks, but it can also hamstring growth and production in future years, compounding problems with languishing prices. This is top of mind for many producers as they grapple with how to keep investors happy and stay out of bankruptcy court. Some producers are better positioned than others in this aspect, particularly Cabot. The chart below shows the relationship between the total amount of debt principal due over the next five years as compared to trailing levered free cash flow. It shows that some companies have some real challenges in that area.

Source: Capital IQ

Strangulation Via Regulation

The Marcellus and Utica Shale plays possess one of the best unused potential advantages in the natural gas world – proximity to the Northeast United States. One of the biggest potential consumers of the vast gas reserves is neighbor to the Marcellus, yet so little of it makes its way to its natural customer base. Why is this? One word: regulation. For example, the Constitution pipeline, approved by FERC in 2014, has been in regulatory purgatory since that time in the state of New York. Fracking is banned in New York and the regional political climate is frigid towards the natural gas industry, to say the least. In the meantime, New York-area utilities are struggling with gas pressure shortfalls for new customers. Also, in a twist of irony, increasing appetite for natural gas in Massachusetts is being met, at least partially, by Russian (yes, Russian) imports. Thus, Appalachia’s oversupply of gas continues to search for markets while the Northeast gets it from elsewhere. When a Russian LNG tanker pulls into Boston Harbor in the winter…that’s a bad sign.

The Ugly

The near-term doesn’t look any prettier when examining broader economic and commodity trends. In fact, some of it is downright ugly. Supply exceeds demand, futures prices remain anemic and huge areas of quality drilling acreage currently have minimal market value ascribed to them. These factors are putting a boot to the throat of producers and keeping valuations from even getting off the ground.

Get Production For Nothing And Reserves For Free

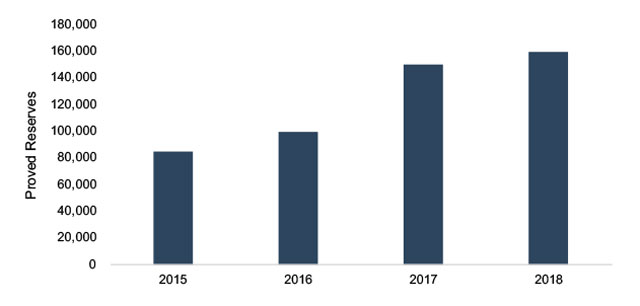

As we consider the supply and demand imbalance right now, we can change the refrain in one of Dire Straits classic songs to “Get Production for Nothing and Reserves for Free.” It can hardly be understated how much the reserves of dry gas in the U.S. have been turned on its head in the past decade. Flippant investors, to the chagrin of some, now view undrilled reserves as a dime a dozen. This was unheard of not long ago. This points out the most fundamental economic driver to these low valuations – oversupply. This hamstrings acreage valuations. According to the 2018 Year End Proved Reserve report which was released in early December, Appalachian dry gas has nearly doubled since just 2015. Even production gain metrics, which surged 48% over this same period, sit in the vapor trail of reserve growth. There is simply too much of a good thing, and it has cheapened gas for everyone else in the Marcellus’ short reach (especially the consumer).

Source: EIA

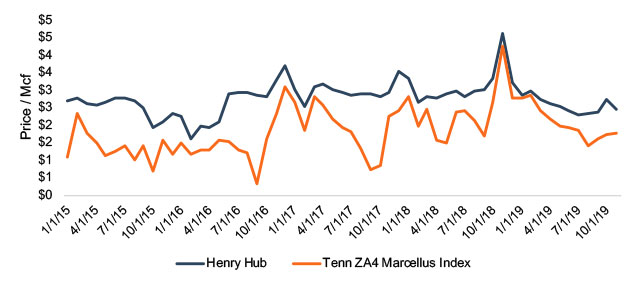

Gas Price Limbo

Even years out, NYMEX gas futures look so flat, it can hardly be called a curve. Like a frantic swimmer getting pulled by an undertow, producers struggle to breathe in this environment. To make matters worse, Appalachia’s regional market constraints make its supply and demand even more imbalanced, leading to consistently wide pricing differentials. What little midstream capacity does come online gets filled too fast to influence pricing power. This has been and remains an Achilles heel for Appalachia.

Source: Bloomberg

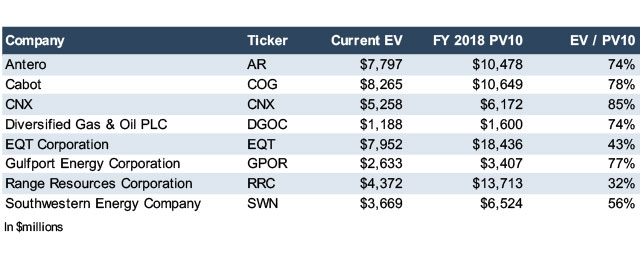

Acreage Values Battling Irrelevancy

At these prices, there are hundreds of thousands of Marcellus and Utica acres that are simply uneconomic. According to a recent analysis by Antero Resources, nearly half (45%) of the needed gas supply in the next four years is currently non-economic at strip prices below $2.48. While that price point doesn’t appear sustainable in the long run, it illustrates why values are so gaunt when it comes to acreage and undrilled reserves. Another way to look at this is to examine companies’ enterprise values as compared to the PV10 values of their proved reserves (including undeveloped reserves), a standardized industry metric.

Source: Capital IQ

None of the companies even gets very close to a ratio of 1:1. Some companies are trading around production reserve values only. Either way one slices it, future drilling inventory does not appear to be particularly valuable in the market’s view at this juncture.

When going through the laundry list of problems that the industry is facing, it can be difficult to see any upside, silver lining or diamonds in the rough. However, if one subscribes to rational market theory, then there are some things, hidden in plain sight, that could make an investor’s journey worth the long ride.

The Good

Intrinsically, Appalachia remains one of the most strategically important gas plays in North America. Eventually, amid all the obstacles it faces, it has arguably the most potential of any shale gas field and could develop into one of the most profitable shale gas fields in the world for decades to come.

Retrenching – Diet And Exercise Pay Off

These challenges are certainly testing the mettle of Appalachian producers. Producers’ intense focus on cash flow has multiple long-term benefits. First, it strengthens balance sheets and makes bankruptcy a more remote concern. Second, the limitations on production growth set a course towards price correction. Third, if and when prices do drift upward, more and more acres become economic. Companies are optimistic about their future. It is notable that Appalachian shareholder returns are manifesting themselves mostly in the form of share buybacks as opposed to dividends. That demonstrates companies believe they are intrinsically undervalued. Remember, the geology and hydrocarbons are there, the question is how cheaply they can be produced. Possibly the most challenging gas environment has forced Appalachian producers to have among the lowest development and operating costs anywhere. Therefore, if producers can survive this, then they can survive and thrive almost anywhere. That’s good because in the future this gas will have places to go.

Oversupply Doesn’t Mean Lack Of Demand

One constant positive for Appalachian producers is that the demand is strong and growing. Platts Analytics estimates that around 80 Tcf of new supply is needed in the U.S. through 2023. Appalachia is expected to supply 38% of that figure. Even with all of the associated gas produced in the Permian right now (which also has logistics issues), it’s not enough. Gas will flow into the Gulf Coast and Appalachia will help lead the way. Globally, natural gas is the only fossil fuel expected to grow in global demand all the way through 2035.

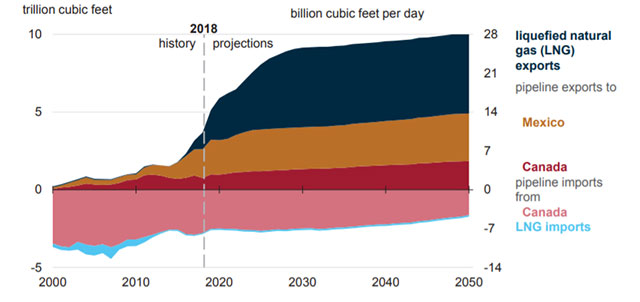

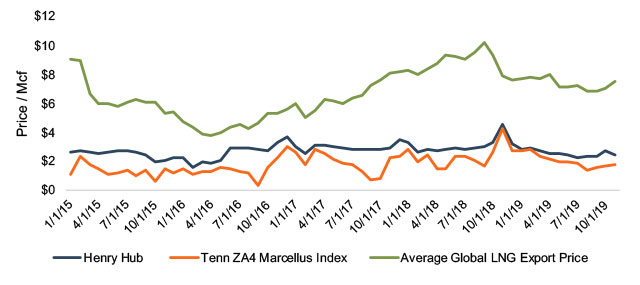

Exports And The LNG Market – A Brass Ring Worth Chasing

The enduring upside for valuations in Appalachia is capitalizing on what’s already in motion: U.S. domination of the worldwide LNG market. It’s not there today, but it is on its way. Between 2017 and 2027, LNG export capacity in the U.S. will have grown tenfold from around 3 Bcf per day to approximately 34 Bcf per day. Price relief for producers could just be a tanker away. Wallowing at $2.50 per MMcf domestically is tough; selling LNG to end markets at up to $9.00 per MMcf is much easier. Global prices are expected to average around $7.00 per MMcf going forward. How does the U.S. fit in this global market? Well, worldwide LNG production growth is flagging, just in time for the U.S. to fill the gap.

Source: U.S. Energy Administration

The Chinese will need energy to engage in any trade wars and American LNG producers will likely supply it over the next 30 years. The U.S. will make up 67% of the growth in global LNG exports through 2024 and China will be the biggest buyer. Looking again at the Appalachian pricing chart overlaid with historical LNG export prices, the opportunity becomes clear.

Source: Bloomberg

A drawback is that compared to the gas basins more proximate to the Gulf Coast, Appalachia has fewer LNG export options. The Elba Island LNG facility is operational, and Cove Point has some capacity, but this pales in comparison to Gulf Coast capacity. At the same time, there are other demand sources, such as Mexico, that will keep overall gas export demand high. Those factors should allow Marcellus and Utica producers more latitude to meet regional demand for east coast population centers. Even if pipeline constraints remain at a minimum, perhaps a tanker with U.S. gas pulls into Boston Harbor instead of a Russian one.

Final Thoughts

One potential wildcard is the possibility of a renewable energy breakthrough. There is certainly a strong sustained desire by many people for this option. However, economically, there are just no alternative sources that can fill the gap in time to meet domestic and international energy and electricity demand. The gap filler is natural gas, and the basin with long-term solutions is primed to be Appalachia. This is the intrinsic valuation premise keeping long-term investors on board.

Originally appeared on Forbes.com.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights