Non-Operating Working Interests in Oil & Gas

Part 1: Characteristics of Non-Op Working Interests, the Risks, and the Benefits

A working interest is an interest in an oil and gas lease, entitling the owner to a percentage of the profits from the oil and gas extracted within a leasehold area. Working interests bear all costs corresponding to the amount of working interest held. For this reason, they are often considered to be like a net profit interest.

However, not all working interests are the same. Broadly speaking, there are two main types of working interests: a traditional operating working interest — sometimes just referred to as a working interest, and “non-operating” working interests (or “non-op” for short).

While the owner of a non-op working interest has an economic or revenue interest in a well or an area of development, they typically have little to no authority or decision-making power

Non-op interests differ from the traditional operating working interests in a critical respect. While the owner of a non-op working interest has an economic or revenue interest in a well or an area of development, they typically have little to no authority or decision-making power in production decisions, activities, or any other operational aspect within the rights and area covered by a lease. That power lies with the contractual operator. However, non-op interests bear the cost burden alongside operating working interest owners, including drilling and completion, workover, lease operating expenses, plugging, etc. In addition, they also only get paid after royalties are paid out first. Royalty interest holders, on the other hand, are not subject to any of these expenses and are typically locked in at a fixed percentage of revenue from the hydrocarbons produced.

Characteristics, Risks, and Benefits

Many operators have a small amount of non-op interests in their portfolio, typically accrued from properties changing hands over time. There are risks associated with non-op interests. There is the possibility of recurring monthly losses if a well becomes uneconomic. But the greater risk — at least from the perspective of operators owning non-op interests — is from not being able to control the development process related to that interest. Especially with unlucky timing, this can slow the pace of getting their own AFEs and ultimately pose severe problems following a drilling plan.

Non-op interests have a different appeal and benefit for certain classes of investors. They provide experience to the investors who want to be involved directly in exploration and production (though may not have the skills) or the capital to do so entirely independently. There also can be attractive buy-in opportunities to assist an operator in financing a development project. Operators needing to source capital for drilling and completion can package a portion of the operating interests and sell it off as non-op interest to an investor who will buy it at the right price.

Non-op interests have a different appeal and benefit for certain classes of investors

One key publicly traded company in this space is Northern Oil and Gas (NOG). NOG primarily functions as an aggregator of non-op interests and seems to think this is a good strategy. In NOG’s Q3 earnings call, CEO Nicholas O’Grady discussed recent trends of operators needing to offload their non-operating working interests amid “shareholder return requirements, dividends, [and] buybacks. They want to drill their own wells … and then they’ve got their own set of budget … They’ve got maybe two obligation wells, but it makes more sense to do cube development and they want to drill six. Well, how do you manage your capital there? You go find that non-op partners, sell your interest … whatever it might be, and you drill additional wells in that regard.”

In some instances, owners of non-operating working interests are charged periodically to pay for their share of the overhead costs incurred by the operator. The rate at which this overhead is charged to the non-op interest owners will inevitably differ from actual overhead costs, which are partially variable. One organization that often plays a role in these contractual relationships between operators and non-operators is the Council of Petroleum Accountants Societies (“COPAS”). Though it has no statutory authority, the organization is influential in modeling standard and widely adopted accounting practices for developing and maintaining joint operating agreements between parties involved in the oil and gas industry. These practices include guidance on how operator costs and overhead are allocated between an operator and a non-op holder.

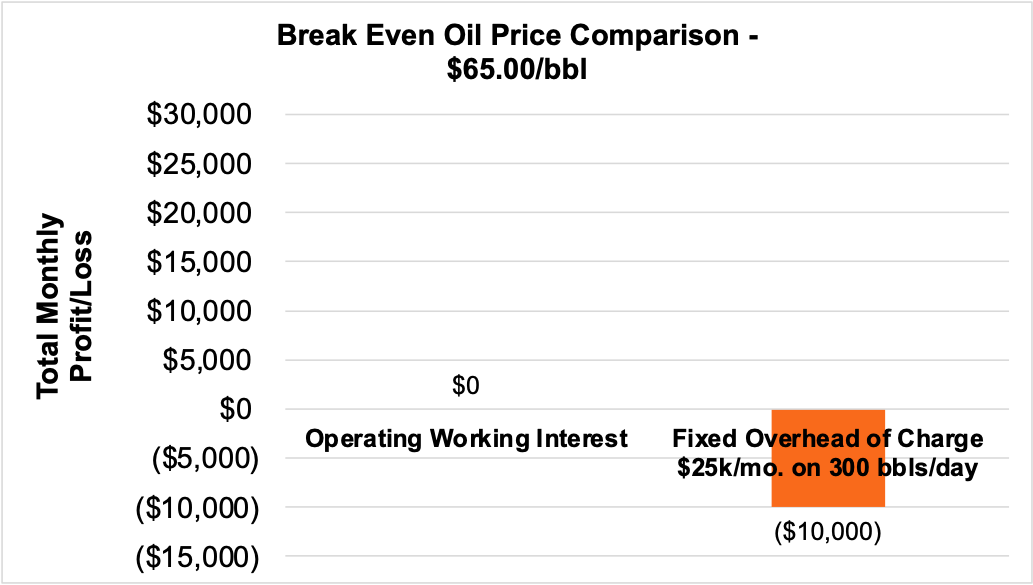

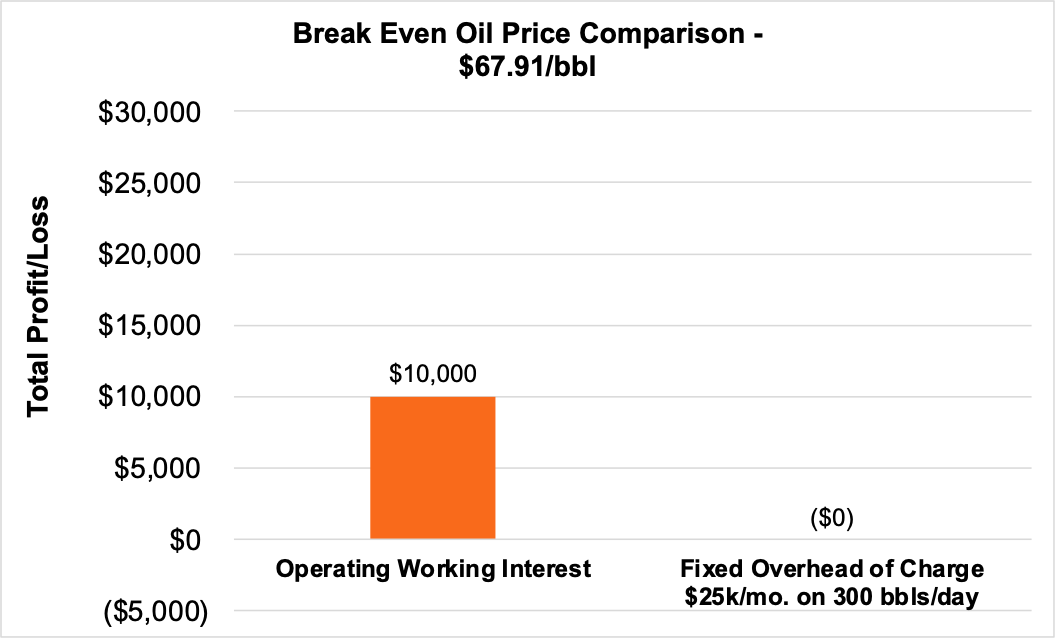

How much overhead is charged by an operator and how it is allocated are critical economic distinctions between operating and non-op interests. If the overhead being charged is higher than the actual cost, profit margins will differ between the operating interest and the non-op interest. In those scenarios, the operating interest will have a lower break-even oil price ($/bbl) than the non-op interest.

As an example, non-op owners are hypothetically charged $25,000/mo. for administrative overhead that only costs the operator $15,000. In addition, this hypothetical joint operating agreement calls for pro-rata overhead allocation. The charts below illustrate the difference in the break-even price points between operating and non-operating interests, both with the exact same costs besides the one overhead component.

As seen above, the economics between an operating interest and a non-op interest can sometimes differ significantly in certain circumstances. This can play a role in the economics and valuation aspects of these two types of interests, which we will cover in part 2 of this series.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights