Oilfield Water Management

Clean Future Act Regulatory Concerns

In the midst of the COVID pandemic, the rise of the Delta-variant, and general summer distractions, not a lot of attention has been given to the 117th Congress’ H.R. 1512 – aka the “Climate Leadership and Environmental Action for our Nation’s Future Act” or the “CLEAN Future Act.” The Act was first presented as a draft for discussion purposes in January 2020. After more than a year of hearings and stakeholder input, it was introduced as H.R. 1512 in March 2021. The Act’s stated purpose is:

“To build a clean and prosperous future by addressing the climate crisis, protecting the health and welfare of all Americans, and putting the Nation on the path to a net-zero greenhouse gas economy by 2050, and for other purposes.”

As broad as that stated purpose is, it’s not surprising just how far-reaching the implications of the nearly one-thousand-page-long Act are for many sectors of the U.S. economy. While Congress is a long way away from any bipartisan climate legislation being enacted, the Act provides some insight regarding the plans of the House Democrat Leadership for a clean energy future. It also potentially serves as a “red flag” to many industry participants that will be materially impacted by those plans.

Of particular interest to the Oilfield Water Management sector, is Section 625 of the Act. In that section, the Environmental Protection Agency would be ordered to determine whether certain oil and gas production byproducts, including produced water, meet the criteria to be identified as hazardous waste. The legislation in fact, mandates that the EPA must make its determination within a year after the Act becomes law.

Per the EPA’s April 2019 study publication, Management of Exploration, Development and Production Wastes: Factors Informing a Decision on the Need for Regulatory Action, produced water is defined as “the water (brine) brought up from the hydrocarbon bearing strata during the extraction of oil and gas. It can include formation water, injection water, and any chemicals added downhole or during the oil/water separation process.” Since 1988, EPA has held that oilfield-produced water should be regulated as non-hazardous waste. As such, produced water has been subject to the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act’s (RCRA) much less restrictive Section D provisions regarding non-hazardous waste, instead of RCRA Section C’s much more restrictive provisions regarding hazardous waste.

Per a June 2021 report by Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, if the EPA’s Act-directed review of the 1988 produced water’s non-hazardous classification is revised to a hazardous classification, an enormous disruption in oilfield water management would result. The report specifies that severe disposal capacity constraints would be brought into play.

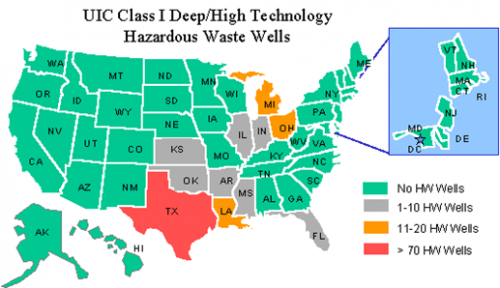

At the current time, oilfield produced water disposal is available at an estimated 180,000 Class II disposal wells located throughout the U.S. If the Act were to lead the EPA to reclassify produced water as hazardous waste, all produced water would have to be disposed of in Class I wells, of which there are far fewer. The EPA’s data on Class I wells indicates that approximately 800 such wells are in existence; however, the wells are located in only 10 states due to geological requirements. The majority of those Class I wells are located in Texas and Louisiana. The EPA also indicates that only 17% of the Class I wells are available for hazardous waste disposal. Adding to the limited Class I well availability matter, the University of Wisconsin Eau Claire reports that those hazardous waste disposal wells are located at a mere 51 facilities.

Source: EPA

The cost of transporting Eagle Ford and Permian Basin produced water (in excess of 10 million barrels per day), for example, hundreds for miles to Class I facilities on the Texas and Louisiana Gulf Coast would be prohibitive to many producers. As a result, a substantial reduction in U.S. oil and gas production would be a natural and expected consequence, with the economic and industry ripple effect of such reduced production being enormous. Gabriel Collins, the Baker Botts Fellow in Energy and Environmental Regulatory Affairs at the Baker Institute, notes that any such re-classification would very likely lead to multi-system disruptions severe enough to make achieving the Act’s climate, energy, environmental, and social objectives impossible.

While the Act is awaiting action by the U.S. House of Representatives, it’s well worth Oilfield Water Management industry participants keeping a close eye on it. Although Congress’ attention has been focused on COVID relief and is now focused on infrastructure matters, the CLEAN Future Act will eventually come to the forefront, with potentially far-reaching impacts if unchanged from its current form.

Conclusion

Mercer Capital closely monitors the Oilfield Water Management and other areas of the Oilfield Services industry. We’re always happy to answer your OFS-related, or more general valuation-related questions. Please contact a Mercer Capital professional to discuss your needs in confidence.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights