Current Commodity Price Environment May Lead to Next Round of OFS Bankruptcies

When I was given the assignment to author this blog post this week, I thought “Could one possibly ‘draw’ a more timely assignment?” Several weeks ago, Mercer Capital’s Energy Team noted that we should consider the current condition of the oilfield services (“OFS”) industry as the topic of one of our upcoming blog posts. The price for West Texas Intermediate (“WTI”) had been declining since mid-February, due largely to decreased demand related to the coronavirus, and the Russia-Saudi Arabia failure to reach an agreement on production cuts. Industry participants were growing a least somewhat concerned – and then came the March 6 news that the Russian-Saudi negotiating difficulties might lead to an actual price war – and then came the March 9 actual start of the price war.

More Possible OFS Bankruptcies? How Did We Get “Here”?

By way of “background,” the U.S. OFS industry went through a major round of bankruptcies following the late 2014 drop in oil prices. From the WTI peak in June 2014 at $106/bbl, prices fell to $58/bbl in mid-December 2014 and on to $30/bbl in January 2016. While there were a couple of upward moves in WTI in April and August of 2015, those were short-lived with the “trend” remaining a fairly clear path downward.

Data provided in Haynes and Boone, LLP’s Oilfield Services Bankruptcy Tracker report (January 2020) show the annual number of identified OFS bankruptcies rising from 33 in 2015, to 72 in 2016, before easing to 55 in 2017 and 12 in 2018. Although the WTI price was generally rising during 2016, the price remained below $55/bbl with the impact of the fall from $60+/bbl pricing continuing to ripple through the industry well into 2017.

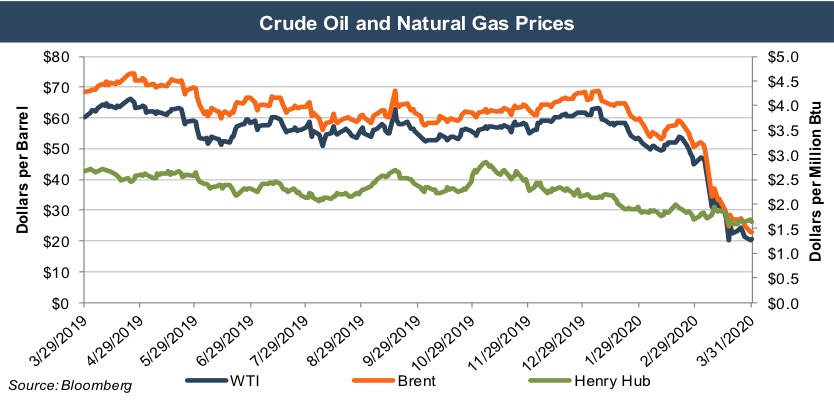

During 2018 – through October – WTI had generally ranged between $61 and $74/bbl. OFS bankruptcies slowed, but the industry was hardly prospering. Many industry participants were more accurately described as “hanging-on” or “maintaining operations” – hoping for a rise in demand, or a drop in supply, to lift prices and move the industry to more favorable profitability. However, in November 2018, rising worldwide inventories caused by global supply running well ahead of demand, fueled in part by the continuing growth in U.S. production, resulted in prices dipping to a low point of $43/bbl in December. While pricing improved somewhat in 2019, with WTI generally between $54 and $64/bbl, the loss of $62+/bbl pricing led to an uptick in the number of OFS bankruptcies late in 2019.

Source: Haynes and Boone, LLP

Source: Haynes and Boone, LLP

Recent Events – Industry and Non-Industry

As we entered 2020, there didn’t seem to be any specific indications of change ahead for oil prices. Few had ever heard the term coronavirus and no one was anticipating a Russian break from OPEC+, or using the term “price war” in regard to the Russian-Saudi failure to reach an agreement on OPEC+ production cuts. The World Health Organization’s China office had begun receiving reports in December of an unknown virus that had led to cases of pneumonia in Wuhan, a major city in eastern China, but the term “outbreak” wasn’t being used.

Within eight weeks that had all changed markedly. By late February we had already gone beyond “outbreak” and had moved on to regularly hearing of the possibility of a pandemic. People and countries began to react. Multiple countries were significantly limiting travel in order to slow the spread of what we all now know as the novel coronavirus, or Covid-19. Quarantines, self-imposed and government-imposed, were reducing economic production and travel, thereby reducing the level of demand for transportation fuels and fuels as a means of production. In addition, it was becoming clear that the Russian-Saudi disagreement on production cuts was more than a minor matter. The possibility of a split in the Russian-Saudi production alliance to maintain oil prices was being actively discussed as having real potential. Oil prices naturally responded with a downward turn, reaching as low as $45/bbl near the end of February.

On Friday, March 6th, it was reported that Moscow had outright refused to reduce its crude production in order to offset the fall in demand related to the coronavirus. Over the subsequent weekend, rumors swirled as to the magnitude of the impasse. Then, on Monday, March 9th, the worst possible scenario for oil prices became more than a possibility. An actual price war was initiated as both Russia and Saudi Arabia announced production increases. The anticipated glut immediately pitched prices into a dive with the WTI falling from $41/bbl to $31/bbl by day’s end for a single-day decline of 24%.

What to Expect

As to what we can expect going forward from here, we don’t know. The coronavirus, now a pandemic, is obviously spreading. How much and how far are the unknowns, along with how large the impact will be on the U.S. and global economy, and thus, the demand for oil. What is know is that oil demand will be down for a time. What’s also known is that the outbreak will eventually be contained and the economic impact reversed when things return to “normal.”

So, What About Oil Supply?

Well, we have two very significant oil exporters, formerly allied on oil production levels, now markedly un-allied on oil production. Not only un-allied, but both purposefully increasing production levels, in the face of lower demand, for the purpose of causing economic pain to each other. Unfortunately, that economic pain radiates, by extension, to all oil producers and the businesses that provide equipment and services to the oil producers. What does that mean for U.S. OFS market participants in the near term? Pain. Economic pain. For those that have more economic “wriggle-room,” better margins, lower financial leverage, more defendable market position, it won’t be good. For those with less of that economic wriggle-room, it could go well beyond “not good.” If the alliance break isn’t remedied fairly quickly and the two belligerents remain belligerent, the production glut could last long enough that a new round of OFS bankruptcies could be in the making.

What’s absolutely certain is the uncertainty of it all – and at least some very real OFS industry economic pain if either the virus impact, or possibly the Russian-Saudi dust-up, lasts long enough to keep oil prices down at the new current level, or an even worse scenario, lower than the current level.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights