Four Questions to Ask About Debt in Your Family Business

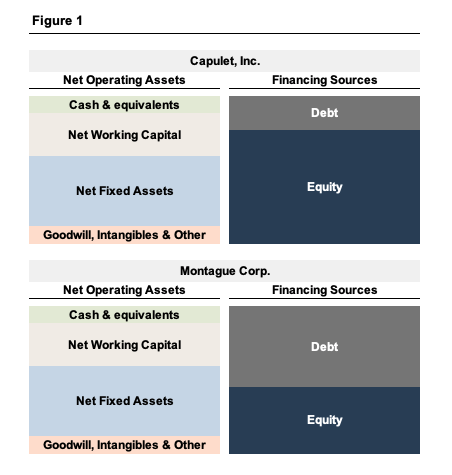

One of the first questions our family business clients ask us is how much debt they should have. We refer to this as the capital structure question. Capital structure is simply the relative proportion of debt and equity capital used to finance a business. Figure 1, depicting a family business balance sheet, illustrates the capital structure decision.

The operations of Capulet, Inc. and Montague Corp. are identical. In other words, the two families have answered the capital budgeting question (“What investments are worthwhile uses of family capital?”) in the same way. However, the Capulets and Montagues have reached very different conclusions regarding the capital structure question (“What mix of debt and equity financing should we use?”). The Capulets have relied primarily on equity financing while the Montagues have favored debt.

Answering the capital structure question well requires considering both business and family characteristics. We find that discerning what the business means to the family is a critical first step. We also find that referencing and interpreting relevant benchmarking data can help families reach consensus when answering the capital structure question. We present benchmarking ratios relevant to the capital structure question in Chapter 6 of the 2019 Benchmarking Guide for Family Business Directors (“the Benchmarking Guide”). In this post, we identify four questions that directors should ask about the use of debt in their family business.

Question #1 – How Good Is Our Collateral?

Rational lenders seek to minimize their risk of loss, and one way of doing that is by identifying the collateral that can be used to secure their position in the event of default. So the first question to ask about debt in your family business relates to collateral – what assets does your family business own that will provide security to a lender?

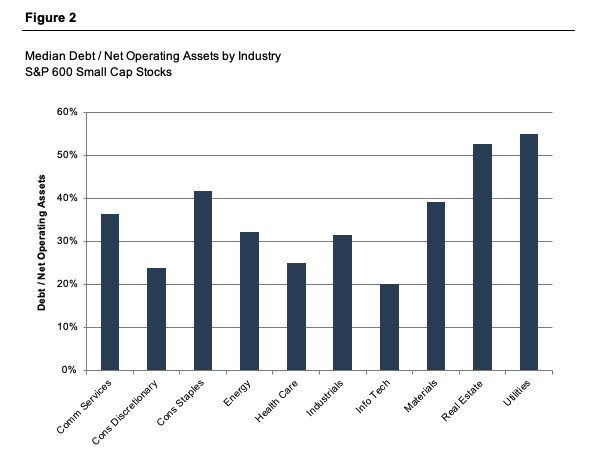

In the consumer context, home and auto loans are often described using the loan-to-value (“LTV”) ratio. The LTV ratio describes the relationship between the amount of debt outstanding and the underlying collateral value. In other words, if you borrowed $30,000 to finance the purchase of your $40,000 car, the LTV ratio on your loan is 75%. In the business context, the analogue to the LTV ratio is the ratio of debt to net operating assets. Figure 2 summarizes data from Table 6.1 of the Benchmarking Guide.

Not all assets are equally useful as collateral. For example, real estate and utility companies have a high proportion of fixed assets having alternative future uses in their asset bases, while health care and information technology company assets tend to be more concentrated in goodwill and intangible assets for which lenders have less enthusiasm.

Smaller family businesses lacking sufficient collateral will sometimes rely on personal guarantees of certain family shareholders to provide security to lenders. This is effectively a subsidy, and all shareholders (both guarantors and not) should be aware of the implications of such guarantees.

Question #2 – Can We Service the Debt?

Collateral value matters most in the event of default. Of course, most family business borrowers would prefer not to enter default. So, the second question to ask about the use of debt in your family business relates to the ability to make timely payments of principal and interest when they come due.

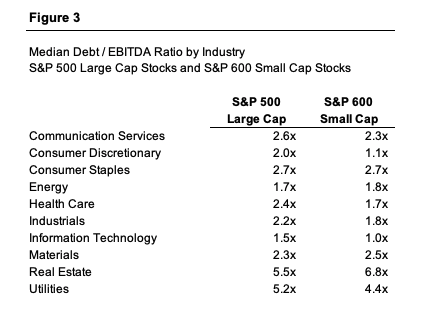

The most common ratio used to evaluate the ability of family businesses to service their debt is the ratio of debt to EBITDA (earnings before interest taxes and depreciation). For a more thorough discussion of the merits and shortcomings of EBITDA as a measure of financial performance, check out this post. Table 6.4 in the Benchmarking Guide presents EBITDA leverage data for public companies. As shown on Figure 3 below, EBITDA leverage varies by industry.

Debt capacity as measured by the Debt / EBITDA ratio depends on the perceived riskiness, or volatility, of cash flow. For example, companies in the consumer staples sector are less sensitive to economic conditions than those in the consumer discretionary sector; as seen in Figure 3, consumer staples companies borrow more per dollar of EBITDA that their counterparts in the consumer discretionary sector. Larger companies are also often perceived to be less risky than smaller companies. With a few exceptions, the large cap companies in Figure 3 have higher Debt / EBITDA ratios than their small cap brethren.

Question #3 – How Much Will It Cost?

The more debt a family uses to fund its operations, the more expensive the debt will be. This is intuitive since the greater the debt balance, the greater the likelihood that lenders will not be repaid. Table 6.6 of the Benchmarking Guide describes the effective interest cost for the public companies in our sample set. Effective interest cost is the quotient of interest expense to the average debt balance for a period.

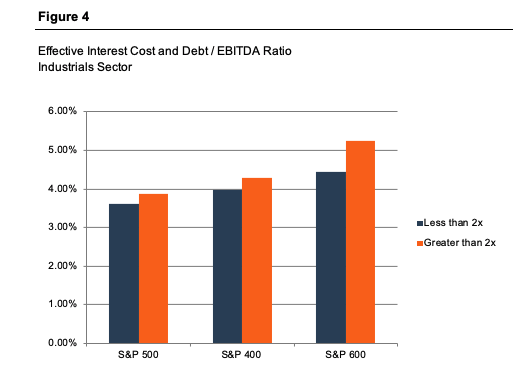

In Figure 4, we pop the hood and look a little deeper at the data, comparing the effective interest cost for companies in the industrials sector. We sorted the companies by Debt / EBITDA ratio, and then computed the median effective interest cost for those companies with leverage ratios less than, or greater than 2x.

While we suspect this analysis would not pass muster statistically, it does confirm the reasonableness of our intuitive hunch that companies with more debt pay a higher effective interest rate, all else equal. The data on Figure 4 also illustrates the effect of company size on risk, with larger companies having lower effective interest costs than their smaller peers.

Question #4 – Will We Be Able to Sleep at Night?

Increasing leverage not only increases the cost of borrowing, it also increases the risk – and therefore cost – of equity. So the final question to ask with regard to the use of debt in your family business is this: Will we be able to sleep at night? Unfortunately, there is no cut-and-dried academic answer to this question. More than anything, the answer depends on the risk tolerances and preferences of your family shareholders.

Observers often focus on the use of debt to minimize the overall cost of capital for a company and thereby maximize its value. And while that may be, to some degree, possible, the increasing costs of debt and equity with leverage mean that the overall cost of capital is relatively flat across a wide span of potential capital structures, as shown in Figure 5.

As shown in Figure 5, the weighted average cost of capital does not vary appreciably across a wide range of potential capital structures. What this suggests is that, for family businesses, the capital structure decision has less to do with increasing the value of the family business and much more to do with financing growth and allocating risk and return among the debt and equity holders. If family shareholders are willing to accept more financing risk, their available returns will be higher. If, on the other hand, the preference of family shareholders is to minimize risk, then they should expect a lower return. Going back to our example in Figure 1, the Capulets bear less risk, but the Montagues have the potential for greater returns. Return always follows risk, and there are no shortcuts.

Conclusion

What’s the right capital structure for your family business? We find that the best answer to that question can be found only after asking a series of other questions: How good is our collateral? Can we service the debt? How much will this cost? And perhaps most importantly, will we be able to sleep at night? Sadly, there are no shortcuts, but the long-term rewards for your family business of answering these questions well can be significant. Capital structure decisions affect the long-term sustainability of your family business and can be costly to unwind. Much better to measure twice and cut once than to arrive quickly at the wrong answer.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director