Why Do Family Businesses Tend to Borrow Less Money?

As recounted in the Harvard Business Review article entitled “What You Can Learn from Family Business,” an academic study of family-controlled and non-family public companies found that debt constituted 37% of the capital of family-run businesses, compared 47% for the non-family companies. This finding is generally consistent with our experience working with family businesses of all sizes. In this post, we consider why family-run businesses might be a bit more debt-shy than their non-family peers.

Debt and Family Business Value

Greater use of low-cost debt reduces the overall weighted average cost of capital.

One of the principal textbook reasons for using financial leverage is to “maximize” the value of the business. According to the theory, greater use of low-cost debt reduces the overall weighted average cost of capital. If the value of a business is equal to the present value of expected future net cash flows of the enterprise, a lower discount rate will result in a higher present value. Since the relevant discount rate for the value of the family business is the weighted average cost of capital, companies that borrow the “optimal” amount of debt will thereby “maximize” their value, or so the theory goes.

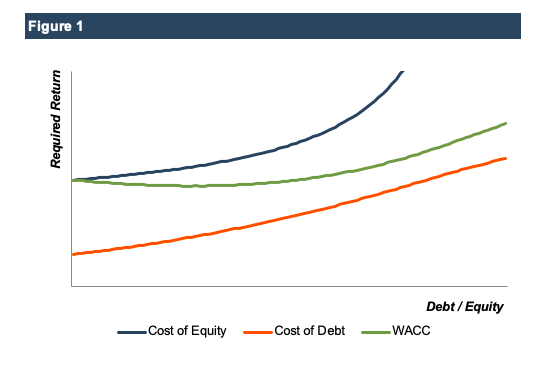

This theory is unimpeachable as far as it goes, but in our view, a couple sizable grains of salt are in order. First, the difference between the current and “optimal” weighted average cost of capital is often quite modest. As shown in Figure 1 below, increasing financial leverage increases the costs of both debt and equity capital.

Because the absolute cost of the capital components is dynamic with respect to the amount of leverage, the resulting weighted average cost of capital is less sensitive to leverage than one might expect. As a result, borrowing money for the sole purpose of “maximizing” shareholder value has the potential to be a fools’ errand.

Second, when family businesses are sold, buyers are focused on the value of the assets (tangible and intangible). Most transactions are structured so that the seller receives a gross amount of consideration which they must then use to pay off any outstanding indebtedness, with the residual serving as the net proceeds to the family shareholders.

- The textbook theory assumes that the company’s shares are freely-traded so that there is a deep and liquid market for minority shares in the company. In that case, the capital structure is a given that will not be affected by trading activity in the shares, and investors are rightly concerned with just what that capital structure is.

- But the reality for most family businesses is that transactions of minority interests in shares are infrequent, and that the relevant market is that in which the company as a whole will transact; buyers in that market are indifferent to the existing capital structure of the seller.

In this way, the market for family businesses is more like the housing market than the stock market. The value of a house does not depend on the size of the mortgage on that house. In the same way, the value of your family business to a potential buyer does not depend on the amount of debt outstanding.

Debt and Returns on Family Capital

If capital structure management doesn’t influence the value of your family business, why does the amount of debt matter?

Why are family businesses willing to accept lower returns in exchange for less risk?

Financial leverage may not change the value of your family business, but it absolutely will influence how the return on invested capital is allocated to lenders and family shareholders. Shareholder returns for a given level of ROIC will be higher the more debt financing is used in the family business. But these higher returns are available only in exchange for bearing greater risk. If, as the authors of the Harvard Business Review study maintain, family businesses do, in fact, use less financial leverage than their non-family peers, why are family businesses willing to accept lower returns in exchange for less risk?

We suspect there are at least two reasons for this preference on the part of family shareholders.

First, the costs of failure for family businesses are much higher than the finance textbook would indicate. In the event of bankruptcy, the shareholders of textbook theory blithely accept the financial loss and continue on their merry way. In contrast, the failure of a family business comes with enormous costs in terms of the socioemotional wealth of the family. The resulting job loss, negative economic impact to the local community, and damaged family reputation weigh heavily on family shareholders but are of no concern to the textbook investor.

Second, family shareholder wealth (and, potentially, income) is often concentrated in the family business. As a result, shareholders are naturally more averse to risk than the textbook investor. If you’re going to have all of your eggs in one basket, you need to do everything in your power to protect that basket. For many family businesses, that defensive posture includes borrowing less money than their non-family peers.

The Financial Value of Resilience

In our experience, successful family businesses use debt judiciously to take advantage of attractive capital investment opportunities, enhance family shareholder returns, and on occasion to promote diversification outside the family business. The finding that, on balance, family businesses tend to use a bit less debt than their non-family peers is consistent with our observations over the years. The authors of the Harvard Business Review conclude that family businesses prioritize resilience over performance.

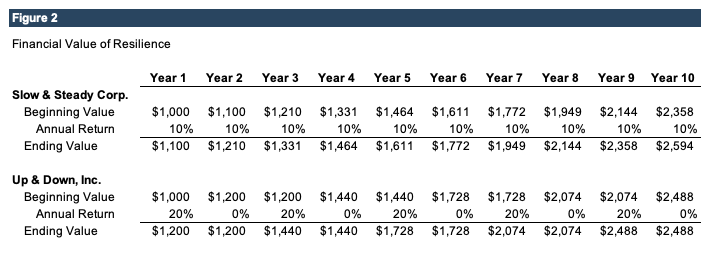

Even apart from the concept of socioemotional wealth, resilience pays dividends in the long run. To illustrate, consider the long-term outcomes for two family businesses: Slow & Steady Corp. earns a 10% return each year, while the returns for Up & Down, Inc. alternate between 0% and 20% each year. The average annual return is 10% for each business, yet, after ten years, Slow & Steady Corp. is worth more than Up & Down, Inc.

If your family business has a long-term horizon, resilience will prove rewarding. Indeed, the Harvard Business Review study found that – over the long-term – the family-run businesses generated superior returns.

Since resilience is rewarded, how are you and your fellow directors enhancing the resilience of your family business through your capital structure decisions?

Family Business Director

Family Business Director