How Much Money Does Your Family Business Really Make?

This post is part of our “Talking to the Numbers” series for family business leaders. In this series of posts, our goal is to help family business directors ask the right questions when reviewing financial statements. Asking better questions will lead to better financial and business decisions.

In our last post in this series, we focused on operating income, which is a critical measure for evaluating the performance of management since it is unaffected by financing and tax decisions made by the board of directors. Net income, on the other hand, reveals how those board-level decisions influence your family business’s earnings and ability to pay dividends. Everyone likes to talk about EBITDA and EBIT – and those are important metrics – but only net income measures the increase in the family’s wealth from owning the business.

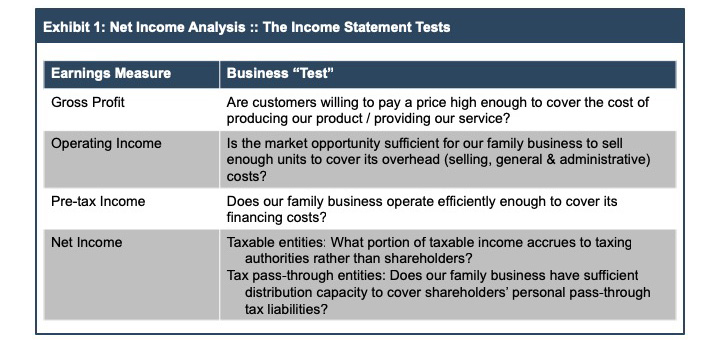

Exhibit 1 summarizes the different “tests” that a family business faces as we move down the income statement.

For the family business to be truly profitable, operating income must be sufficient to cover financing costs. And taxes are a fact of life, so Uncle Sam must take his share before the real profitability of your family business can be discerned.

Financing Costs

Analysts often refer to operating income as EBIT, or earnings before interest and taxes. Interest expense is the cost of financing the portion of the family business funded by debt. All financing sources – both debt and equity – have costs, but only the cost of debt is measurable by accountants. (We’ll address the cost of equity in a future post.) So interest expense is what shows up on the income statement.

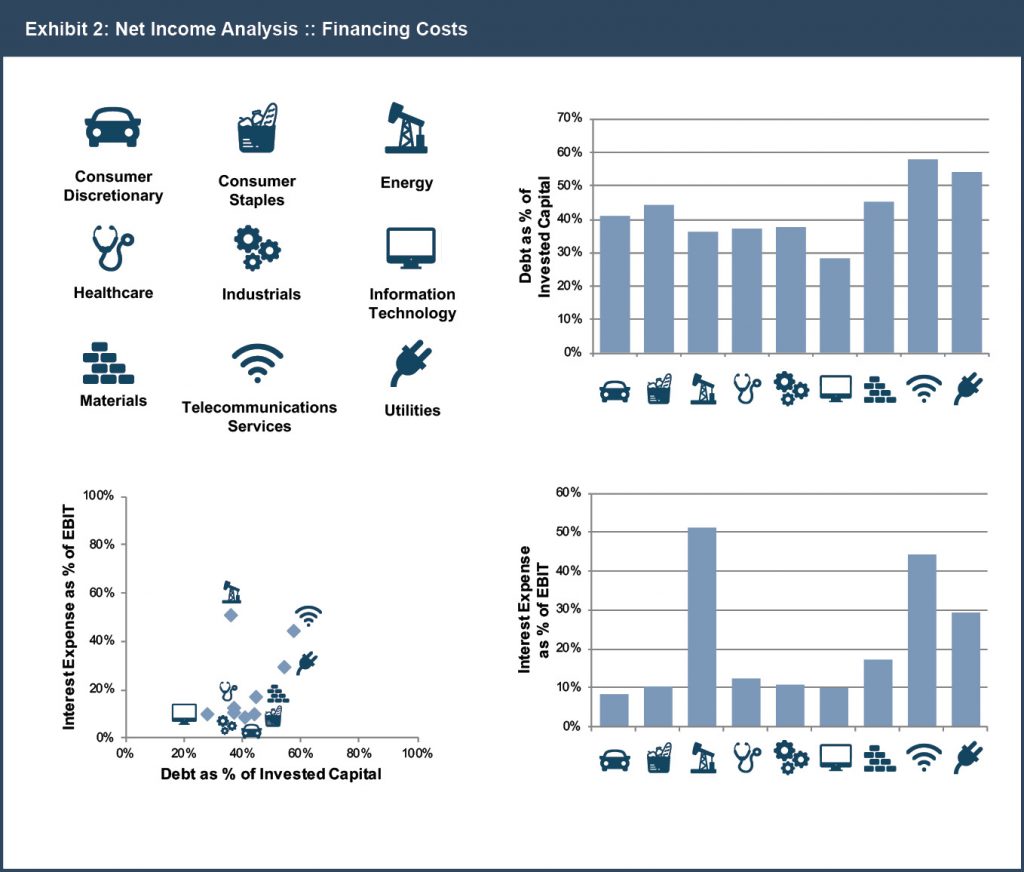

The amount of interest expense on the income statement depends on the amount of debt on the balance sheet and the rate charged by lenders. The relationship between balance sheet leverage and interest burden for our data set is summarized in Exhibit 2.

Reviewing the data in the exhibit above, we can discern the strong positive correlation between balance sheet funding and the interest coverage ratio. The principal exception to this relationship is in the energy sector, where depressed operating earnings have increased the proportion of EBIT that is required to pay interest costs.

How risky is your family business from an operating perspective?

From a balance sheet perspective, companies tend to use more financial leverage in industries that rely on large investments in physical assets (telecommunications and utilities), and less in industries that rely more on human capital and intellectual property (such as information technology).

From an income statement perspective, recurring revenue and predictability of earnings are also indicators of debt capacity. To illustrate this, we sorted the companies in our data set into two groups on the basis of observed year-to-year volatility of EBIT. The companies demonstrating less volatility had median debt to invested capital ratios of 43%, while the median for companies in the higher volatility group was 35%.

For family business directors, the key questions around financing costs include:

- What is the appetite for risk among our family shareholders? Are our family shareholders willing to accept greater financial risk in exchange for the opportunity for higher returns?

- How risky is our family business from an operating perspective? Do we have good visibility into future earnings from year-to-year, or do operating earnings vary markedly from period to period?

Income Taxes

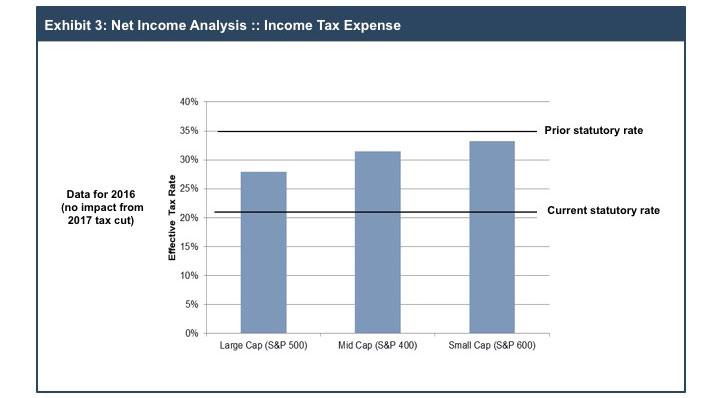

Unlike financing costs, income taxes are proportional to pre-tax earnings. As a result, income taxes do not affect the risk profile of a family business, but they do influence the returns – and dividend paying capacity – of a family business. We make a couple observations when studying our public company data set, both of which are evident in Exhibit 3.

First, the effective tax rate for public companies (income tax expense as a percentage of pre-tax income) has historically been less than the prevailing statutory rate. Second, the effective tax rate is inversely related to company size: the effective tax rate for large cap companies in our data set was just under 28%, while the effective tax rate for small cap companies was a bit over 33%. We suspect this is attributable to a couple factors: (1) the largest companies likely have the greatest access to the most sophisticated and effective tax strategies, and (2) the large cap companies likely earn a greater portion of their income in lower-tax international jurisdictions than do small cap companies.

How does your family business’s effective tax rate compare to the statutory tax rate?

For family businesses, there is the added wrinkle of deciding whether to adopt a tax pass-through structure. Many family businesses elect to be organized as S corporations (or other pass-through forms), while public operating companies are generally organized as C corporations. While the S election eliminates one layer of taxation, it is not necessarily the optimal structure for all family businesses, particularly following the implementation of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

The most important thing for family business directors to understand about the S election is that the legal and economic consequences of the election are reversed. Legally, the S election removes the obligation to pay income tax on corporate earnings from the corporation. However, economically, the S election relieves shareholders of the obligation to pay dividend tax on distributions from the corporation.

Let’s unpack that a bit.

Though an S corporation does not have to write a check to the IRS, its shareholders are required to do so for the full amount of taxes on the earnings “passed-through” to the shareholders. These taxes are due whether there is a corresponding distribution from the company or not. Therefore, an S corporation has to make a distribution to its shareholders sufficient to make them whole on the pass-through tax liability they are now legally obligated to pay. So from an economic perspective, the company still has to pay taxes on its income; those taxes are just routed through the shareholders as distributions. But having paid those taxes, the shareholders have no further obligation for taxes on additional distributions received from the family business.

As a result, the economic benefit of the S election to family business shareholders will be most pronounced for businesses that have the capacity to distribute a substantial portion of net (after tax distribution) earnings. Shareholders of family businesses that do not plan to make significant after-tax distributions may, in fact, be worse off under an S election, since the personal tax rate (29.6% assuming eligibility for the qualifying business income deduction) is higher than the C corporation tax rate (21%).

Family business leaders should seek answers to the following questions when thinking about income taxes:

- How does our family business’s effective tax rate compare to the statutory tax rate? Are there available strategies that could reduce – or at least defer – the tax drag on net income and dividend capacity? A penny of taxes saved really is a penny earned.

- Should our family business be organized as an S corporation? What is the likely future relationship between dividend payments and earnings reinvestment? What used to be a slam-dunk analysis in favor of the S election is no longer nearly so straightforward. The reduction in C corporation tax rates may have tipped the scales back in favor of C corporation status for some family businesses.

Conclusion

So how much money does your family business really make? EBITDA is an important measure for a lot of reasons, but there are significant claims on the cash flow measured by EBITDA before it trickles down to the family shareholders. As a family business director, the decisions you make with regard to financing and tax structure can have a material effect on how much money the business really makes. Contact one of our experienced family business advisory professionals today to discuss how best to approach these important decisions.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director