Managing the Family Business in an Era of Cheap Capital

One of the hottest topics in the financial press these days are special purpose acquisition corporations, or SPACs. According to one report, SPACs have already raised almost 3x the capital for investment during 2020 as they did during all of 2019. SPACs, also known as “blank check companies,” are publicly traded entities that raise capital from investors to acquire one or more companies. As noted on the SEC’s website, the promoters of SPACs have often not yet identified the company to be acquired at the time of the capital raise.

SPACs are not new, and there are a few potential explanations for their popularity this year. We suspect that at least part of their appeal, however, can be traced to the willingness of investors to accept more risk to generate higher nominal returns.

- Despite a few cyclical upticks, interest rates have steadily ground downward over the past decade, with the so-called risk-free rate, or return on long-term Treasuries, falling from about 4.5% in early 2011 to less than 1.5% today. The incremental return premium for investing in stocks instead of bonds, known as the equity risk premium or ERP, eludes direct observation, but Aswath Damodaran – a widely respected finance professor – estimates that the ERP currently stands somewhere between 3.4% and 5.8%. Adding the two components together, let’s assume the current cost of equity for large public companies is around 7.0%.

- On the debt side, borrowing costs for corporate borrowers are also quite low, with the current yield for BBB-rated issues at less than 2.5%. Adjusting for the tax deductibility of interest payments, the after-tax borrowing cost for investment-grade borrowers is currently less than 2.0%.

- Assuming a moderate capital structure composed of 20% debt and 80% equity, the resulting weighted average cost of capital for large cap public companies is 6.0%.

For public companies, the almost endless supply of cheap capital (as evidenced by the proliferation of SPACs) is a boon. The low cost of capital makes it easier to justify investment opportunities (whether for capital spending or acquisitions) financially, and investors are willing to provide capital in search of higher returns.

For many family businesses, however, the era of cheap capital may not be an unqualified good. Many families have a deep-rooted cultural aversion to relying on non-family equity capital. The abundance of equity capital searching for a good home is therefore not a benefit they can access, at least not through traditional channels. Such constraints on family capital can also limit practical access to cheap debt financing. As a result, many family businesses cannot load up at the capital buffet as readily as their public counterparts.

As a result, cheap capital can create trigger pressure and tensions in both the business and the family.

- For the managers of the family business, the reality is that they are competing with firms who are aggressively taking advantage of the low cost of capital. Holding the line on the family business’s hurdle rate for capital investment will likely result in lost opportunities and slower growth. As one of my colleagues is fond of saying, it is an alternative investment world. Family businesses cannot set their hurdle rates and return expectations in a vacuum. Of course, the cost of capital for most family businesses remains well north of 6.0%. However, the returns available to family businesses are influenced by the returns available in the public capital markets. Directors need to be intentional about either (1) accepting lower prospective returns on potential capital investments, or (2) acknowledging that the family business could lose share to competitors.

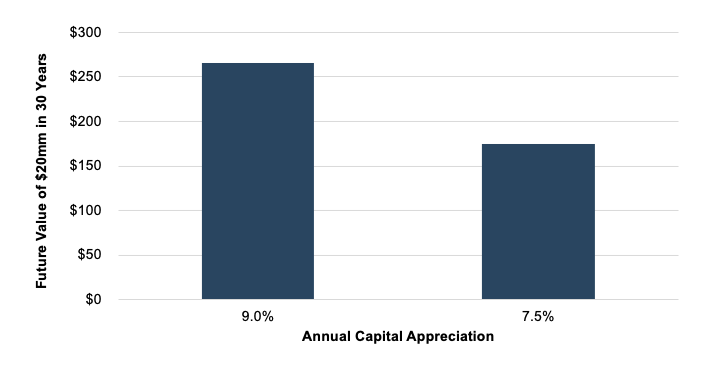

- Family shareholders may need to re-calibrate their expectations for the long-term returns on the family business. If a rising tide lifts all boats, the opposite is also true. Shaving 100 or 200 basis points off annual return expectations has a profound effect on per capita wealth over the course of two or three decades, as illustrated in the following chart. Compounded over 30 years, a 1.5% decrease in annual capital appreciation reduces the family’s future wealth by 34%.

This can have far-reaching consequences for the family’s lifestyle, community impact, and philanthropic ambitions. Return follows risk. Family business directors need to be closely attuned to family shareholders’ risk preferences and return objectives. If shareholders’ return objectives do not align with their professed risk preferences, there are likely some hard conversations ahead. Candid shareholder communication today can forestall family dissension tomorrow.

Selling the family business can serve as a release valve for these building pressures. However, selling the family business does not make all of the family’s problems go away and can even introduce a few new ones. How will your family business adapt to this era of cheap capital?

Family Business Director

Family Business Director