Who’s In and Who’s Out?

The intersection of family and business generates a unique set of questions for family business directors. We’ve culled through our years of experience working with family businesses of every shape and size to identify the questions that are most likely to trigger sleepless nights for directors. Excerpted from our recent book, The 12 Questions That Keep Family Business Directors Awake at Night, we address this week one of these key questions and offer possible next steps.

As family businesses evolve, the family’s leaders need to determine the appropriate relationship between membership in the family and ownership in the business. As the third, fourth, and subsequent generations of the family reach adulthood, it becomes increasingly likely that the interests of at least some family members will diverge from the interests of the business.

Family businesses can adopt one of two broad strategies to address this situation:

- Maintain broad-based ownership and make positive shareholder engagement a strategic priority; or,

- Use share redemptions and liquidity programs to achieve concentrated ownership among a subset of the family.

Neither strategy is inherently superior to the other. We discussed the benefits (and challenges) of developing positive shareholder engagement in Chapter 1. In this chapter, we focus on the second strategy.

Motivations for Selling Shares

In this chapter, we focus on voluntary, rather than involuntary, sales of shares. Involuntary sales of shares include those triggered by, and governed by, the relevant terms of the company’s buy-sell agreement. Chapter 8 provides a brief overview of the issues associated with buy-sell agreements.

In some families, selling shares in the family business is perceived as nothing short of treason. Yet, there are often legitimate reasons for family members to sell shares in the family business, such as a desire for diversification, proceeds to start a new business venture, or funding education or other major life events.

In our experience, the desire of family shareholders for liquidity (whether full or partial) can usually be traced to some form of “clientele” effect. The clientele effect names the fact that a company’s shareholder base is not monolithic: different shareholders have different portfolios, risk preferences, income needs, and expectations. In multi-generation family businesses, we find the clientele effect to be common. As the family grows numerically and spreads out geographically and occupationally, it is only natural for shareholders no longer to look so much alike. Differing shareholder needs and preferences are not wrong, but when treated as such, the resulting suspicion can lead to resentment, open conflict, and in too many cases, litigation.

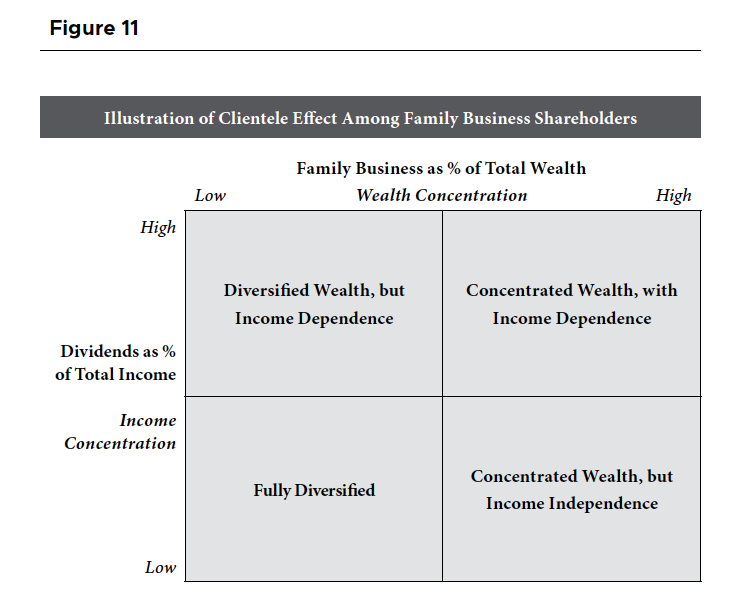

Shareholder clienteles can form along many different potential axes: kinship, geography, employment status, etc. To illustrate the concept, consider the economic role the family business can fulfill in different households, as depicted in Figure 11.

It is only natural that family members in the upper right quadrant view the family business very differently from their cousins or siblings in the lower left quadrant. Those in the upper right quadrant are likely to be very risk-averse, desiring preservation of capital and the current level of dividends above all else. Shareholders in the lower left quadrant will much more closely resemble public market investors, supporting corporate strategies that enhance returns at acceptable risk levels.

For public companies, the clientele effect sorts itself out because shareholders self-select; if the attributes of the company don’t align a shareholders preferences and risk tolerances, it is very easy for the shareholder to sell their holdings and find assets that are a better fit. For family businesses, however, things are not nearly so tidy.

Faced with multiple shareholder clienteles, family business leaders can seek to adopt distribution and reinvestment policies that accommodate as many shareholders as possible. Or, the family can adopt a formal share redemption or liquidity program with a view to providing shareholders greater flexibility in tailoring the economic benefits of family membership to the unique circumstances of their particular household.

Elements of a Shareholder Liquidity Program

While every shareholder liquidity program is unique, there are certain structural elements that all plans, whether formal or informal, must have.

Buyer

There has to be a source for the liquidity made available to selling shareholders. The default assumption is generally that the business will redeem the shares sold under the plan. However, the available liquidity pool may be supplemented by individual shareholders who are able and willing to purchase additional shares.

- If the business redeems shares, the ownership of all the non-selling shareholders increases on a pro rata basis, resulting in no change to the relative ownership. And, since the business is paying for the shares, the redemption will either reduce the company’s liquid assets and/or increase the company’s indebtedness. In either case, the redemption changes the financial risk profile of the family business.

- If shares are instead purchased by other family shareholders, the relative ownership of the buying shareholders will increase. Further, the company’s financial position is unaffected, since it is serving the role of matchmaker, but is not actually a party to the transaction. If there are shareholders with the financial capacity and willingness to purchase additional shares, the family can benefit from having a liquidity program that does not take capital away from the business.

Frequency

Liquidity may be available on a continuous basis or at specified intervals. A continuous plan provides the most flexibility for shareholders, but restricting redemptions to specific dates (annual or potentially even less frequent) is generally more efficient and predictable for the managers of the business, and allows the business to accumulate capital to fund the redemption.

Availability

Liquidity plans generally include caps on the aggregate dollar amount of liquidity to be made available, whether to individual shareholders or in total. Higher caps increase the perceived value of the liquidity program to family shareholders, but at the cost of greater uncertainty to the business. As noted above, however, the uncertainty to the business can be hedged, or even eliminated, if some or all of the purchases are made by other shareholders rather than the company.

Terms

Liquidity programs may provide for immediate cash payment, or require the selling shareholder to accept a note upon tendering their shares. While selling shareholders generally prefer cash, using notes (or a combination of notes and cash) increases the company’s flexibility and may allow for a larger redemption pool. If the terms of the note issued in exchange for shares feature a belowmarket interest rate, the economic value of the transaction will be less than the nominal price.

Pricing

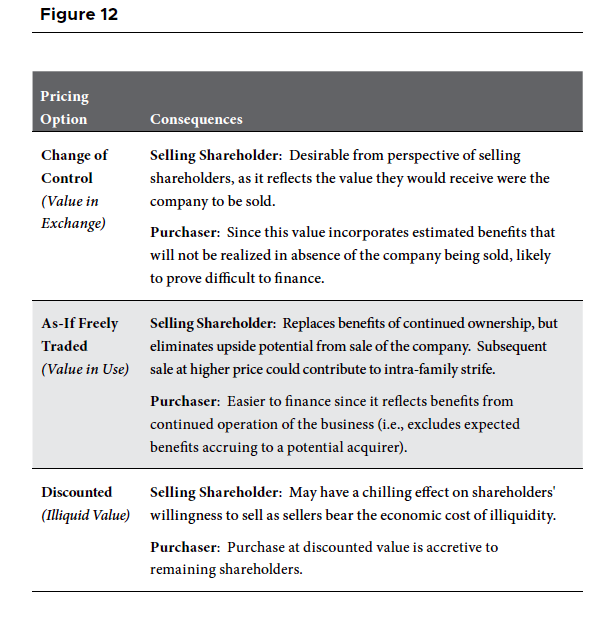

Finally, a liquidity program must specify the price at which shares can be sold. There are essentially three options for the price to be paid, and each option has consequences for the selling and non-selling shareholders.

- Change of Control. The first option is a change of control value. This is akin to the value in exchange for the business. The change of control value contemplates that potential acquirers may anticipate making changes to the business to increase cash flow. If the acquirer is a so-called strategic acquirer, the magnitude of such changes can be quite large. While selling shareholders would prefer to receive a change of control value, it can be difficult for the company (or purchasing shareholder) to finance the purchase since the business is not actually being sold and will presumably continue to be operated with the existing level of cash flow.

- As-If Freely Traded. The second option mimics how the company’s shares would be priced if they were traded in the public stock market. If the change of control value is value in exchange, the as-if freely traded value is value in use. The as-if freely traded price contemplates that the business will continue as an independent entity, so incremental benefits to be expected by a potential acquirer are not included in the projected cash flows. While this value is less attractive to selling shareholders, it is more feasible for the purchaser (whether the company or another shareholder) to finance the purchase at this price. If the company is later sold to a strategic acquirer, shareholders taking advantage of the liquidity program may feel taken advantage of themselves.

- Discounted for Illiquidity. Finally, the price used in the liquidity program may include a discount to reflect the illiquidity of family business shares. Investors prefer to have the ability to easily sell their shares, so it is widely acknowledged that minority shares in private companies are worth less than otherwise comparable shares that are publicly traded. Redemptions at a discounted price confer an economic benefit upon the non-selling family shareholders. Stated alternatively, use of a discounted price imposes an economic penalty on the selling family shareholders. Whether that is desirable or not depends in large part on the family’s posture toward selling shareholders (i.e., is selling stock akin to treason?).

Figure 12 summarizes the various consequences of the different pricing options.

There is no inherently “right” choice for the price to be used in a liquidity program. The company’s directors should weigh the consequences of the various options noted above against the objectives of the liquidity program for the family.

Implementing the Liquidity Program

An effective and sustainable liquidity program should be predictable. Predictability is achieved by having clearly-defined terms that are well-understood by all interested parties, and having regular appraisals of the company’s shares prepared by a qualified independent business valuation expert. A qualified business appraiser will perform periodic valuations on a consistent basis, taking into account the financial performance of the family business, fundamental changes in the operations and outlook for the business and the industry, as well as relevant market changes. At the direction of the company, valuations can be prepared at any (or all) of the three levels noted above.

Implementing a liquidity program increases the importance of shareholder education. If family shareholders are going to have the ability to sell shares, they need to do so on an informed basis. It is essential that selling shareholders have a firm grasp of the company’s financial performance and strategy, and understand the key factors that drive the valuation.

Liquidity programs are not cure-alls, but when carefully designed and implemented, they can relieve many of the pressure points that face growing multi-generation family businesses.

Potential Next Steps

- Identify existing shareholder clienteles and determine the needs, objectives, and preferences of each

- Assess the company’s financial capacity to support an ongoing shareholder liquidity program

- Determine whether the company or other shareholders will be buyers supporting a shareholder liquidity program

- Define the frequency, size/availability, and terms of a shareholder liquidity program that best meet the objectives of shareholders and the needs of the business

- Define the level of value to be used for shareholder liquidity program purchases

- Obtain a qualified independent business valuation at the selected level of value

- Design education and communication tools to ensure that shareholders are well-informed regarding the liquidity program

Family Business Director

Family Business Director