What Is a “Level” of Value, and Why Does it Matter? (Part 3)

In last week’s post, we demonstrated how critical getting the level of value right is for family businesses for estate planning, acquisitions, and divestitures. We conclude our series on the levels of value this week, by turning our attention to shareholder redemption transactions.

Shareholder Redemptions

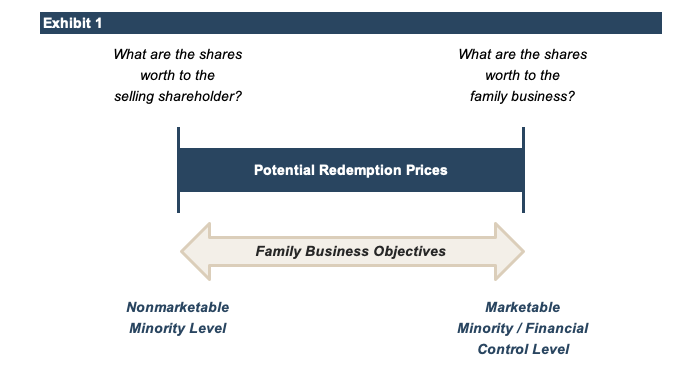

A shareholder redemption is a purchase by the family business of shares from a family shareholder. As with our corporate development and divestiture examples from last week’s post, shareholder redemptions reflect an inherent tension between buyers and sellers, as illustrated in Exhibit 1.

In a shareholder redemption transaction, the buyer and seller do not share the same perspective.

- The selling shareholder owns an illiquid minority interest in a private business. As a result, the fair market value – the amount that a hypothetical willing buyer would pay – reflects a marketability discount. In other words, the nonmarketable minority level is relevant.

- However, in a shareholder redemption transaction, the buyer is not a hypothetical party, but the company that issued the shares in the first place. The family business is not burdened by the illiquidity of the shares in the same way a shareholder is. As a result, the value of the shares to the family business is consistent with the marketable minority level of value.

It strikes us as a bit perverse to evaluate transactions between family shareholders and family businesses in terms of relative negotiating leverage. Instead, we prefer to frame the decision in terms of family business objectives: What is the purpose of the redemption?

The “correct” price at which to conduct a shareholder redemption transaction is always a bit ambiguous. Consider the alternatives:

- Nonmarketable Minority Level. This seems straightforward – after all, that is the fair market value of what the shareholder owns. Why should the family business pay any more than that?

- Marketable Minority Level. On the other hand, this is the value of what the redeeming company is acquiring. Why should the family business pay any less than that?

From an economic perspective, a redemption at the nonmarketable minority level is accretive to the non-selling shareholders. Redeeming at the marketable minority level provides a windfall to the selling shareholder relative to the fair market value of their shares. There is no simple escape from this dilemma.

- If the family business wants to discourage redemption requests, the nonmarketable minority level of value may be preferable.

- If the family business is designing a shareholder liquidity program with a view to promoting positive shareholder engagement, it may be desirable to conduct redemptions at the marketable minority level of value. However, in such cases it is essential to set limits on the amount of redemption requests the family business will honor in a given period; otherwise, the liquidity program could trigger a “run on the bank,” crowding out corporate investments critical to the long-term sustainability of the family business.

- If the objective of the redemption is to “prune” the family tree of unwanted branches, it may be necessary to pay a redemption price at the marketable minority / financial control level of value. Depending on state statute, it may be a legal necessity. In any event, the departing shareholders are likely to demand such pricing to exit the family business.

Conclusion

In this series of posts, we have explained what the levels of value mean. Your family business has a different value at each level of value because of differences in expected cash flows and risk factors. Considering four common corporate transactions, we have illustrated why the level of value matters to family businesses:

- When transferring minority interests among family members in furtherance of estate planning objectives, the fair market value of the interests transferred is properly measured at the nonmarketable minority level.

- When considering a potential acquisition, family businesses should evaluate both the marketable minority / financial control level of value (what the target is worth to the existing owners) and the potential strategic control level of value (what the target is worth to the family business). These two values for the target define the relevant range for negotiating a transaction price.

- When divesting a business, the dynamics are reversed. The relevant negotiating range is set by the difference between the marketable minority / financial control level of value (in this case, what the business is worth to the family) and the strategic control level of value (what the business is potentially worth to the buyer). The family can improve its negotiating leverage in these situations by differentiating the business from other available targets and exposing the business to multiple motivated buyers.

- Finally, shareholder redemptions can occur at either the nonmarketable minority or marketable / minority financial control levels of value. The appropriate level for a given transaction should be selected with a view to the objectives of the redemption for the family business.

These transactions can have profound and long-lasting economic implications for the family business and its shareholders. When the stakes are high, it’s a good idea to measure twice and cut once. When your family business is preparing for any of these transactions, give one of our valuation professionals a call.

See Part 1 of this series here.

See Part 2 of this series here.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director