Marking Illiquid Investments in Liquid Funds

This guest post first appeared on Mercer Capital’s Financial Reporting Blog on March 14, 2016.

As mutual fund flows continue to favor passive strategies, some active fund managers are beginning to look to alternative asset classes to augment returns and generate sustainable alpha. Since open-end funds need to calculate NAV on a daily basis, the inclusion of illiquid venture capital investments in liquid funds shines a brighter spotlight on fair value measurement.

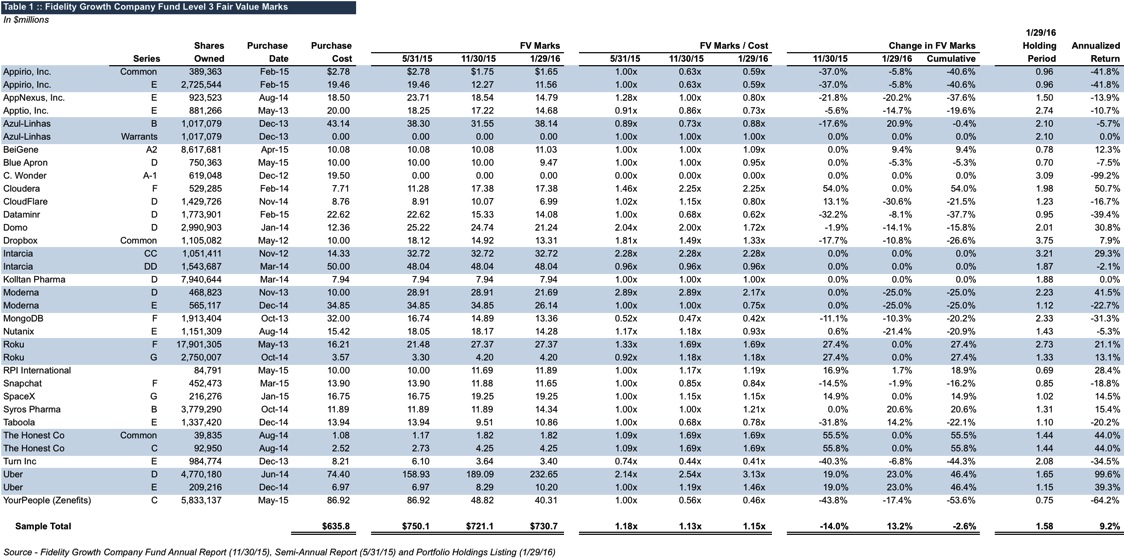

Fund giant Fidelity has garnered the most attention for their venture capital fair value marks. Table 1 summarizes relevant data for a sample of investment holdings in 27 venture companies held by the Fidelity Growth Company Fund (FDGRX).

At the end of January 2016, the reported fair value of the Level 3 venture investments on Table 1 totaled $730.7 million, or 2.0% of total fund assets at that date.1 We offer the following observations:

- It is clear that a fair value process is being followed. While the range of reasonableness for these investments can be wider than what is typical for more liquid investments, Fidelity does not appear to be allowing fair values to become stale. Of the 34 individual positions in the sample, 23 reported changes in fair value during the two months between November 30, 2015 and January 29, 2016.

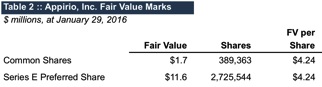

- Fidelity disregards a prominent tenet of the reigning fair value orthodoxy, which is that the fair value of shares within a complex capital structure must take into account the unique economic rights and attributes of the individual classes. In the sample of investments presented in Table 1, the fund owns multiples securities in seven enterprises (the shaded rows). With the single exception of a warrant in Azul-Linhas, the fair value marks are identical, on a per share basis, for the different classes. This outcome is consistent with determining the fair value of the enterprise and dividing by the fully-diluted share count.

In our experience, this approach reflects the thinking of actual venture investors (who, presumably, count as market participants). Auditors, on the other hand, tend in our experience to require using a probability-weighted expected return method or option pricing method to allocate enterprise value to the various classes. While this technique is theoretically superior, it is in conflict with market participant perspectives on value. Since fair value is explicitly a market participant concept, this raises an interesting philosophical issue: how should fair value incorporate market participant perspectives with regard to valuation techniques? The fund’s financial statements are audited by a Big 4 firm. Clear, uniform guidance around this issue would be most helpful to both reporting entities and fair value measurement specialists.

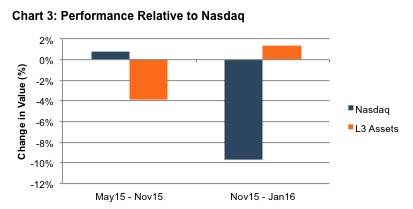

- Non-systematic factors are a significant component of fair value measurement. While the sample is admittedly small, the observed changes in fair value bear no discernible relationship to changes in the Nasdaq composite.

For venture companies, operational and developmental milestones drive value much more than overall market performance and near-term economic data.

- The venture investments were accretive to net asset value per share during the period. Compared to the cumulative loss of 2.3% on the venture investments, the aggregate NAV per share for the fund declined 13.9% over the same period.

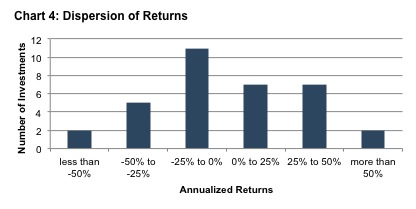

- Calculated from the respective investment dates, the venture investments have posted an aggregate annualized return of 9.2%. The dispersion of results for individual investments has been quite wide, however.

Of the 35 individual positions in the portfolio, sixteen have generated annualized returns (positive and negative) in excess of 25%. Venture investing is not for the faint of heart. The fund’s investment in Uber has performed quite well (99.6% annualized return for Series D and 39.3% for Series E). Without Uber, the overall return on the venture portfolio decreases from 9.2% to negative 7.8%.

Whether venture investing on the part of mutual fund managers is ultimately a good idea is a topic for another day. However, the fair value disclosures surrounding such investments are a treasure trove of information for curious observers. The disclosures bring a measure of transparency to the fair value results for a respected market participant within an asset class for which fair value inputs are difficult to support with precision.

Related Links

- Unicorn Valuations: What’s Obvious Isn’t Real, and What’s Real Isn’t Obvious

- Updated: Valuation Best Practices for Venture Capital and Private Equity Funds

- Are VC trends the canary in the RIA coal mine?

- Preferences and FinTech Valuations

Endnote

1 We excluded investments made subsequent to May 31, 2015 from the table to enhance comparability over time. Including such investments, Level 3 assets at November 30, 2015 totaled $1.2 billion, or 2.4% of total assets at that date. The Portfolio Holdings Listing at January 29, 2016 does not segregate Level 3 assets.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights