RIA Compensation and Valuation: A Conundrum of Brobdingnagian Proportions

Part 1

1958 Lotus Elite (series 1) | Marc Vorgers

Most of the history of race car development focused on creating larger and more complex motors that would generate greater amounts of horsepower. The tradeoff, frequently overlooked, was that a car has to be in scale with the motor, so more horsepower meant a larger and heavier car. A heavier car is more difficult to handle in corners and requires larger brakes. In racing it consumes more fuel (so more pit stops), and a more complex motor is necessarily less reliable.

Colin Chapman was one of the first race car designers to recognize the tradeoff between power and weight, and his mantra, “add more lightness,” inspired a whole generation of sports cars. Chapman’s first road car, the Lotus Elite, had a small and simple, in-line four cylinder motor which only produced about 105 horsepower. What made the Elite competitive was that the car weighed only about 1,000 pounds (the current generation Chevy Tahoe can weigh six times that), so it handled like a dream and could travel at 130 mph. Consequently, the Elite won its class at Le Mans six years in a row.

A similar tradeoff in an investment management firm’s business model is that of compensation expense versus profit margin. Compensation is almost always the largest expense on an RIA’s income statement and has a direct impact on net income.

One of my earliest memories of working with clients in the RIA space was standing in the corridor of a $2 billion AUM equity manager one afternoon as the staff was packing up to go home. The managing partner took the opportunity to show me around the empty office and explain the business model to me: “Our assets get on the elevator and go home every night.”

Yet the most popular rule-of-thumb metric for valuing RIAs isn’t price per employee, but price to AUM. The value of an RIA is not an accumulation of talent, but an accumulation of client assets that produce a healthy profit – after paying for things like talent. The contribution of client assets to profitability may be more consistent than the contribution of talent assets. “The meter’s always running,” my senior analyst at the time told me.

The truth, of course, lies somewhere in-between. Managed assets produce a revenue stream which, after paying for rent and research and maybe a nice client dinner or two, must be divided between the staff (who service clients, manage the shop, and manage the portfolios) and the ownership of the firm (who may or may not be actively involved in operations). At Mercer Capital, our internal language to distinguish the two is return to labor and return to capital. Choosing how to allocate returns between labor and capital often says everything about an RIA’s business model.

A Tale of Two Managers…

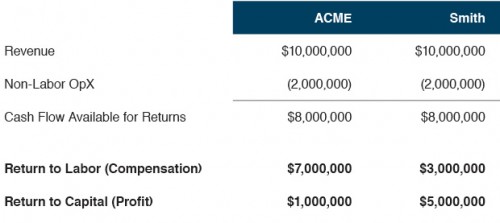

Take a look at the following pair of asset management firms: ACME and Smith. Both generate $10.0 million in revenue, and both spend $2.0 million on non-personnel related expenses. In both cases, that leaves $8.0 million to pay staff and provide a dividend stream or other return to shareholders. At this point the similarities end, and because of differences in compensation structure and the resulting differential in margins, Smith is five times as profitable as ACME.

Since we are a valuation firm, the question we are most likely to be asked at this point is, which firm is worth more: ACME or Smith? That’s an interesting question which deserves more than a little thought. I can think of several occasions where we have been confronted with this very question both formally, when we were working out the share exchange on two similar RIAs with different expense and margin structures, and informally, when we coincidentally valued two very similar firms (for different projects) with approximately the same differential in their respective P&Ls as ACME and Smith.

On the basis of activity alone, maybe ACME and Smith are worth the same. If they have a similar fee schedule, then similar revenue implies similar AUM. But Smith is five times more profitable than ACME, so doesn’t that mean Smith is worth, if not five times as much, at least considerably more? Absent conflicting information, the answer might be yes. Of course, there’s usually conflicting information.

“Why” Matters More Than “What”

Consider the possibility that ACME and Smith are both equity managers serving high net worth and institutional clients. Each employs the same number of staff, and each operates in markets with similar labor availability and costs of living. Now we know a lot of “what” there is to know about ACME and Smith, but we don’t know enough of “why” they show the differential in margins.

ACME operates in a state with a high corporate income tax rate, but no personal tax rate, so they pay out owner distributions in the form of bonuses that inflate compensation expense and deflate margins. Smith is neutral on the tax issue, but has a minority private equity owner that insists that partners are paid only modest salaries such that performance is rewarded for all owners, both inside and outside, via shareholder distributions.

So Which Firm is Worth More?

On the basis of the narrative above, ACME and Smith might be worth about the same. The market for talent being what it is, we might normalize the income statements of both companies and get to a similar margin structure (we will cover how to do that next week). Similar profits might yield similar valuations, but there is a business model difference which matters as well. ACME has more flexibility in its compensation structure and could bonus staff based on ownership and/or performance. This might be a recruiting advantage in the never ending war for talent, thus garnering better “assets” for ACME that will make it more successful than Smith. So is ACME worth more? As a shareholder in Smith, you might be concerned about the firm’s ability to recruit talent, but you would not be concerned about sharing your distribution stream with that talent. So maybe the Smith shareholder has less upside, but that upside is better defined.

The corollary to Collin Chapman’s “add more lightness” here might be to give up on expensive talent and focus on margin, because profits are why businesses operate in the first place. Demonstrated profitability beats adjusted profitability any day. Alas, the early Lotus cars were not known for durability (Chapman also thought that a race car that wasn’t falling apart at the finish line was overbuilt), and skimping on talent to the point that it impairs the longevity of an RIA does little to improve the value of the firm.

Simple, huh?

Next week we will finish the thought with Normalizing Compensation Expense.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights