Saudi Arabia, Russia, or the United States – Did One of the Players Blink?

It’s been a truly dizzying time in the world of international oil production over the last five weeks. With so much macroeconomic activity, twists and turns, it’s been easy to fall behind as to “what’s gone on”, and for even those who’ve been paying reasonably good attention, you may not be sure what all has occurred. What suggestions were made? What deals were cut? What cooperation was gained? What threats were made, and who, if anyone, “blinked”? To some extent, we may never know the answers to all those questions.

How We Got Here

So, what occurred in the last few months that got us to this very dynamic point in time? To summarize:

January-February 2020 – The coronavirus “goes” pandemic, spreading throughout the world. While the full extent of damage from the pandemic remains unknown, it’s expected that at least 2 million people will contract the virus, the death toll will easily surpass 120,000 and the economic damage will be of a magnitude that hasn’t been seen in several generations. Due to the need for quarantines, travel restrictions, forced business shutdowns and stay-at-home orders to limit the spread and speed of the spread, oil demand plunged and oil prices sagged.

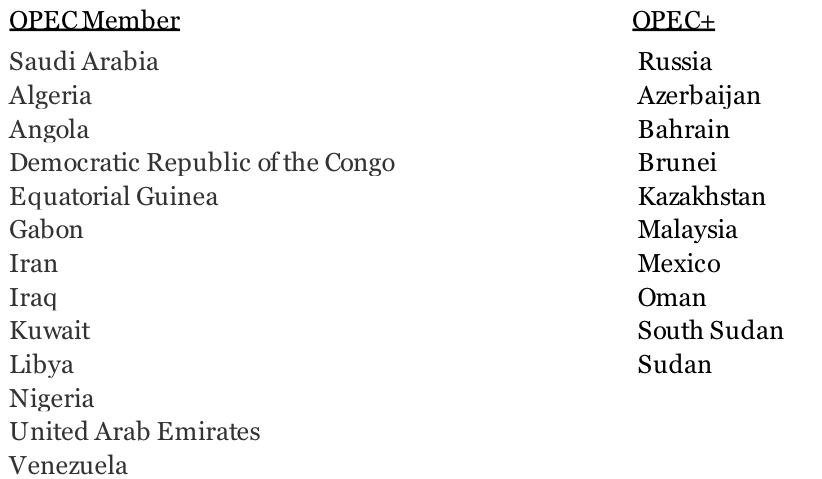

March 6, 2020 – The three-year OPEC+ (OPEC represented by Saudi Arabia and “+” effectively meaning Russia) production/price cooperation pact, set to expire on March 31, fell apart when Moscow refused to support Riyadh’s demand for additional production cuts aimed to offset the reduced demand for oil resulting from the coronavirus pandemic.

March 8, 2020 – So what do two strong-willed centrally-run countries do when their oil production control negotiations (for the purpose of supporting oil prices, on which both countries rely) break-down? Keep negotiating? Give-in a little for their mutual good? No. Instead they purposefully shove their thumb into the other party’s eye by boosting production? Make sense? Not really. Unless there are ulterior motives in-play such as, curbing the U.S. shale revolution that buoyed the U.S. to energy/oil independence and the top spot in world oil production. Not a certain motivation, but a potential motivation that has a lot of people talking about the possibility.

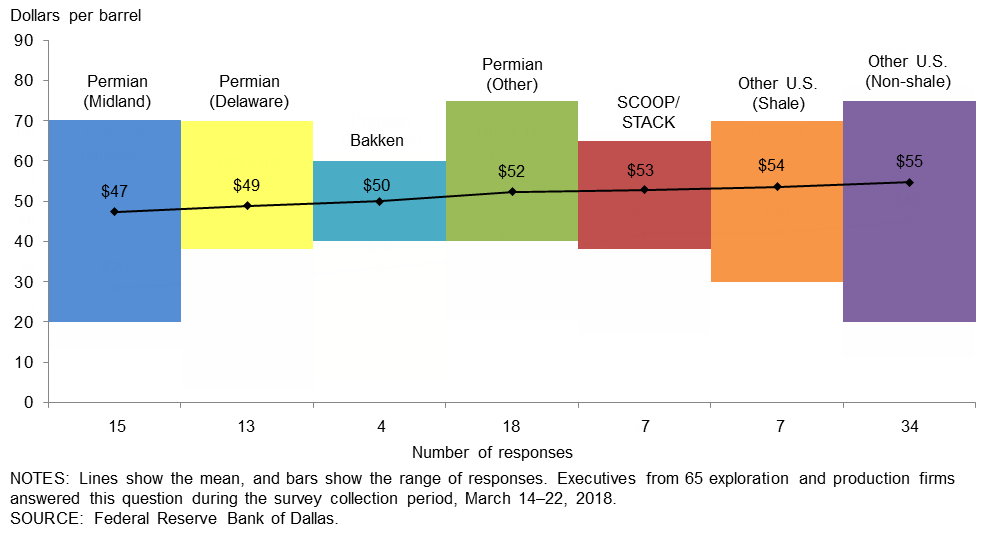

Late March 2020 – At this point, Covid-19 has significantly reduced oil demand. In the meantime, the Saudis and the Russians have boosted oil production and oil prices have tanked. The U.S.’s shale producers are in free fall with bankruptcies staring them in the face. U.S. energy independence and oil production leadership are in the crosshairs and the Saudis and Russians are showing no signs of any rational behavior on energy production. Here’s where the geopolitical, oil-production-tied-relationships game starts to get “interesting”.

What’s a Newly Leading Oil Producer With a Threatened Leading Position to Do?

It’s at this point that all sorts of possible actions on the part of the U.S. begin to be discussed. Various suggested actions include:

Lure Saudi Arabia away from OPEC and into a production-setting relationship with the U.S. – This one was simply a bit hard to imagine having much of a chance at all. First, the U.S. has always been very critical of production controlling cartels, and production setting with the Saudis would be the exact opposite of our long-held free-market values. Second, U.S. anti-trust laws simply wouldn’t allow the U.S. government to engage in limiting production, or oil companies to join together for the purpose of controlling oil production.

That being said, the Wall Street Journal reported in late March that officials at the Energy Department were seeking to convince the Trump administration to push for Saudi Arabia to quit OPEC and work with the U.S. to stabilize oil prices. At the same time, Hart Energy was reporting that Energy Secretary Dan Brouillette had indicated that he didn’t know if a U.S.-Saudi oil alliance was going to be presented as a path forward in any formal way as a part of the public policy process, and that no decisions regarding any such alliance had been made. However, it was also reported that the Trump administration would soon send a special energy representative from the Energy Department, to Saudi Arabia, in order to improve talks between the two countries. Brouillette also indicated that the Trump administration would at some point engage in some sort of diplomatic effort with Saudi Arabia and Russia on oil production levels and that he would work with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and other officials on that effort. This all left the likelihood U.S.-Saudi cooperation open to individual interpretation.

U.S. Production Limits Via the Texas Railroad Commission

Although the U.S. government may be prohibited from entering into oil production agreements by anti-trust laws, that’s not the case for individual states. In late March, reports began to surface of the Texas Railroad Commission having been approached by two major Texas oil producers with the idea of negotiating for production limits with OPEC. The Texas Railroad Commission? Despite the Commission’s name, it long ago ceased any regulation pertaining to the railroads, however, its regulation of Texas oil production (control granted to it back in 1919) continues to this day. Although the Commission has long had a reputation for markedly lenient regulation of production levels, the current crisis has powerful voices calling for the Commission to consider working with OPEC to reduce production levels in order to save the U.S. oil industry from the devastating impact of sub-$25/barrel oil prices.

While this may pose a “workable” process, it comes with multiple layers of required cooperation and agreements. Does the Commission address OPEC directly, or through the Trump administration? OPEC itself requires member cooperation, and the Commission would need the cooperation of other U.S. oil producing states. After all, if the Commission limited production in Texas, but such limits simply triggered higher output in other U.S. states, the effort would be for naught. President of the Texas Oil & Gas Association (TXOGA), Todd Staples, commented on that very matter indicating that if Texas oil and gas operators cut back production in isolation, that reduced production would likely be filled by operators producing in other states.

Even if the Commission’s involvement gained the necessary cooperation from the Trump Administration, OPEC and other states, the idea faces headwinds both from a purely practical standpoint and from those that simply don’t want the Commission involved in the production quotas. Some additional items on the practical side of things:

- Wayne Christian, the Commission’s Chairman, noted that the Commission hasn’t imposed such limits in more than 40 years, the Commission doesn’t have staff with any experience in implementing production limits, the Commission would have to track production across thousands of independent producers, and the Commission’s technological capabilities for handling such a process are quite limited.

- The Commission’s next meeting was, at that time, weeks away on April 21st, meaning that no action in pursuit of limiting production levels would occur for some time.

- Other high oil producing states, unlike Texas, don’t have similar regulatory bodies to the Texas Railroad Commission. Without such regulatory bodies, those states may not have the ability to effectively limit in-state oil production.

Even if these practical barriers could be overcome, there remain powerful voices that are opposed to any moves that go beyond market forces. Mike Sommers, the CEO of the American Petroleum Institute, has pushed back against proposals that would involve U.S. officials negotiating a joint production cut with OPEC and Russia. Sommers noted that the U.S. has always supported the market as the determinant of oil prices, and that during times of crisis, those principles shouldn’t be abandoned. Sommers was particularly opposed to the proposal from a Texas Railroad Commission commissioner, that would regulate oil production within Texas. Commissioner Sommers further indicated that any such proposal would be damaging to our posture in the world, and that imposing a production quota on Texas produced oil would penalize the most efficient producers while supporting less efficient companies. Frank Macchiarola, Senior Vice President of Policy, Economics and Regulatory Affairs at the American Petroleum Institute echoed Sommers sentiments indicating that the Institute’s position is very simple– quotas are bad. He added that quotas have been proven to be ineffective and harmful, and that there’s no reason at this time to be imitating OPEC.

However, Texas Railroad Commission commissioner Ryan Sitton noted that he’d already spoken with OPEC Secretary-General Mohammad Barkindo regarding an international agreement that would ensure economic stability as the world recovers from the coronavirus outbreak. Sitton stated that Barkindo had invited the commissioner to OPEC’s meeting in June to further discuss the matter. Commissioner Sitton further noted that international cooperation was absolutely necessary if Texas were to decide to limit production. He commented that if Texas limited production as part of an international agreement to balance the markets, he thought the odds of success would be very good. However, he further noted that if reductions were only implemented by Texas, without collaboration with others, the odds of success were near zero.

Forget the “Carrot”, Use the Stick

Of course, there’s always those in favor of the straight-forward approach to motivating others to a preferred course of action through of the “stick”, rather than the “carrot”. Especially those that view the Saudi-Russian production spikes as an overt attempt to damage the U.S. shale oil industry. Senators, including Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and John Hoeven of North Dakota, noted that the American people are not without recourse in responding to the Saudi-Russian actions. They’ve noted that tariffs and other trade restrictions, investigations, safeguard actions, sanctions, and much else are within the arsenal of potential responses. Another similarly minded suggestion is to remove U.S. armed forces from the Saudi kingdom.

Others, such as oil industry analyst Ellen Wald indicate that the best option for U.S. in this situation is for the Trump administration to pursue diplomatic efforts to settle things down. Wald noted that sanctions and embargoes aren’t realistic and will having a negative impact for the United States. Sitton seemed to concur with Wald’s position indicating that a diplomatic solution and planned production cuts would be better for everyone. He added that although the Trump administration could embargo Russian and Saudi oil as a form of punishment, his hope was that we don’t end-up going there.

Interestingly, suggested use of these more “stick” type actions have not been coming from the Trump administration. Instead, President Trump has remained more measured in his comments, only noting that if the Saudis and Russians didn’t resolve the matter on their own in short-order, that he would get involved at the appropriate time.

The Art of the Deal

President Trump, ever the deal-maker, may be looking to a solution that avoids violation of the U.S. anti-trust laws, sidesteps brokering a deal on behalf of the Texas Railroad Commission and doesn’t include the actual application of any “stick” – although maybe using the threat of the “stick.” Within the last week, President Trump tweeted that he expected Russia and Saudi Arabia to agree to cut production by millions of barrels a day. Although the Kremlin soon thereafter denied any talks with the Saudis, officials from the kingdom then noted that they would consider significant production cuts as long as other members in the G-20 group of nations were willing to join the effort. On April 9, OPEC and Russia announced plans to reduce their oil production by more than 20%, albeit also indicating that they expect the U.S. and other top producers to join the effort to prop-up prices. U.S. officials noted that while they had not committed to any specific cuts in production, expectations were that U.S. output would fall substantially over the next two years, sounding ever so much like the U.S. is on-board with participating in the reductions, albeit without crossing the line into anti-trust law triggering commitments. However, one sticking point to the agreement was Mexico, who on April 10 balked at the plan. Mexican President Lopez Obrador refused to sign-off on the agreement as it would necessitate putting his plans for Pemex’s revival on hold. That resulted in Obrador getting a call from President Trump from which the U.S. seemed to be offering to take part of Mexico’s required production cut with some sort of undefined “repayment” to occur at a later date. Ultimately, a deal was reached, with OPEC+ nations agreeing to reduce output by 9.7 million barrels per day, representing approximately 10% of global demand before the coronavirus pandemic. However, with demand down an estimated 35%, the cut does not fully balance supply and demand. Oil prices were largely unchanged on the news of the agreement.

Conclusion, or Lack Thereof

As we indicated, it’s been a truly dizzying time in the rough-n-tumble world of oil production. Like they say, if you miss a day, you miss a lot. For now, it at least appears that someone may have just blinked. The Trump administration seems to be on the verge of a truly historic deal to cut worldwide oil production and bring oil prices up to a modestly workable level. And that with the U.S. not committing to forcing domestic producers to cut production levels but indicating that U.S. production would “naturally” decline without the government’s intervention. That coupled with a potential side-deal with Mexico to “cover” part of the production decrease that was being sought from that country, but that Mexico is unwilling to shoulder on its own. Will it work? Will the deal be accomplished?

Although an agreement was reached to reduce oil production in light of demand destruction caused by the coronavirus pandemic, oil markets appear to remain oversupplied. Will OPEC+ and other nations agree to another deal to further reduce production? Will U.S. production decline faster than anticipated due to low oil prices? Will the Texas Railroad Commission implement proration orders for Texas producers? All we can say is, stay tuned – and expect the unexpected.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights