This article discusses the concept of fair market value and its various effects. First, we explain what fair market value means. Then, we explore the hypothetical negotiations between potential buyers and sellers when determining fair market value and the implications of these discussions.

Finally, we examine the impact on the so-called "marketability discount for controlling interests" by analyzing this "discount" from three perspectives: the meaning of fair market value, the integrated theory of business valuation, and the recurring and incorrect rationales for this discount.

Fair Market Value Defined

Fair market value occurs at the intersection of hypothetical negotiations between hypothetical willing, knowledgeable, and able buyers and sellers. Therefore, in every fair market value determination prepared by business appraisers, it is critical that both buyers and sellers are present for the negotiation.

A fair market value appraisal should reflect considerations of both buyers and sellers and land at the intersection of their negotiations over the expected cash flows, growth, and risks associated with receiving those cash flows, whether for a business or an interest in one.

Every appraisal involves the specification of the relevant standard, or type of value. Fair market value is the most frequently used standard of value employed by business appraisers. Many times, appraisers cite a definition of fair market value and list the eight elements listed in Revenue Ruling 59-60 ("RR 59-60") in their reports. The definition of fair market value found in RR 59-60 is:

2.2 Section 20.2031-1(b) of the Estate Tax Regulations (section 81.10 of the Estate Tax Regulations 105) and section 25.2512-1 of the Gift Tax Regulations (section 86.19 of Gift Tax Regulations 108) define fair market value, in effect, as the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller when the former is not under any compulsion to buy and the latter is not under any compulsion to sell, both parties having reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts. Court decisions frequently state in addition that the hypothetical buyer and seller are assumed to be able, as well as willing, to trade and to be well informed about the property and concerning the market for such property.

The eight elements listed in RR 59-60 are as follows. (I call these the "Basic Eight Factors")

- The nature of the business and the history of the enterprise from its inception.

- The economic outlook in general and the condition and outlook of the specific industry in particular.

- The book value of the stock and the financial condition of the business.

- The earning capacity of the company.

- The dividend-paying capacity.

- Whether or not the enterprise has good will or other intangible value.

- Sales of the stock and the size of the block of stock to be valued.

- The market price of stocks of corporations engaged in the same or a similar line of business having their stocks actively traded in the free and open market, either on an exchange or over-the-counter.

Fair Market Value Reflects Hypothetical Negotiations

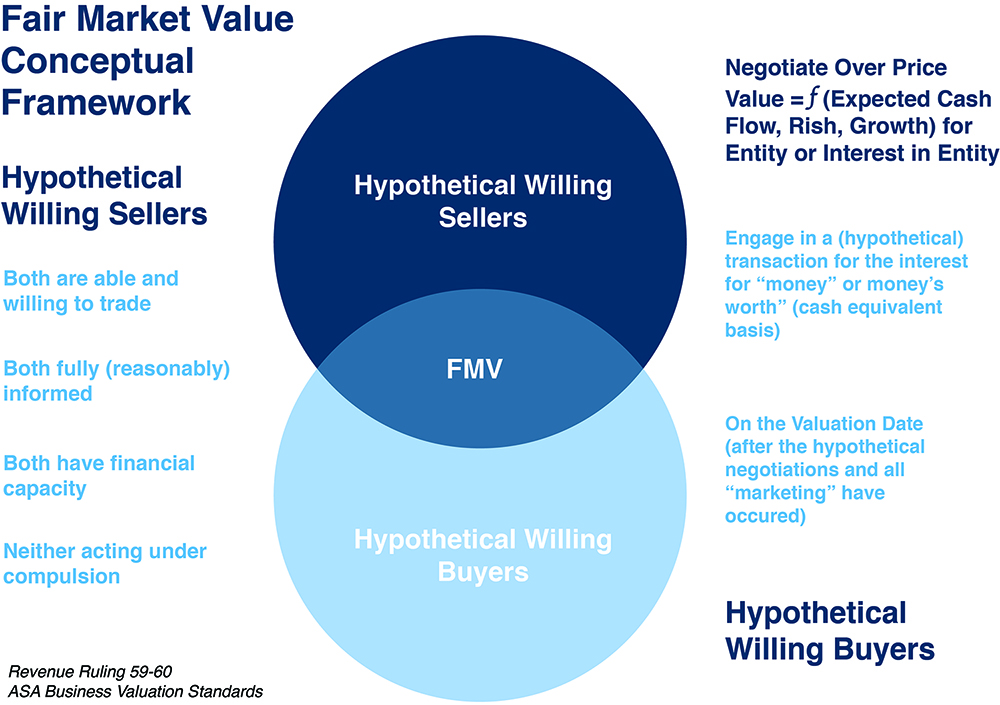

The following figure provides a conceptual look at fair market value. The key elements from the definitions are highlighted around the figure. Hypothetical willing sellers have different interests than do hypothetical willing buyers.

In the world of fair market value:

In the world of fair market value:

- Hypothetical buyers are seeking to acquire expected business cash flows and negotiate price based on their associated risks and expected growth (from their viewpoints).

- Hypothetical sellers, who, if a transaction occurs, are giving up the expected business cash flows that the hypothetical buyers are acquiring, must consider the very same risk and growth factors (from their viewpoints). They negotiate price based on these factors.

- Hypothetical (or real) buyers desire to pay the lowest possible price, but that is not fair market value.

- Hypothetical (or real) sellers desire to receive the highest possible price, but that is not fair market value, either.

- Fair market value necessarily assumes that:

- All hypothetical negotiations and marketing of the subject interest have occurred prior to the consummation of any hypothetical transaction, which occurs on the valuation date.

- Each party to the hypothetical negotiations has taken into account all relevant information that is known or reasonably knowable as of the valuation date.

- The hypothetical parties have agreed to and signed the documentation customarily needed for a transaction prior to or on the valuation date.

- A hypothetical transaction occurs on the valuation date.

Fair Market Value Assumes a Hypothetical Transaction on the Valuation Date

Fair market value assumes that both hypothetical buyers and hypothetical sellers are knowledgeable, willing, and able to transact, and that neither acts under any compulsion. The hypothetical parties negotiate at arm's length and in their respective self-interests. And they engage in a hypothetical transaction with the following characteristics:

- The transaction occurs for money or money's worth, i.e., for a cash-equivalent price.

- The transaction occurs on the valuation date. This fact is critical to understanding fair market value. We address this issue in more depth below.

The So-Called "Marketability Discount for Controlling Interests"

The question of whether a marketability discount should be applicable to controlling interests of businesses has been around for a long time. I addressed the question in an article in the Business Valuation Review of the American Society of Appraisers in 1994. The answer to the questions was, and still is, no. I have addressed this issue in several books and numerous articles and blog posts since then.

The Definition of Fair Market Value

Let's first address the question based on the definition of fair market value, which represents a hypothetical transaction in a subject interest on the valuation date for cash or its equivalent. If there is a hypothetical transaction for a controlling interest in a company, say Acme Manufacturing, on the valuation date for cash at fair market value, what possible reason could there be for discounting that value for "lack of marketability?" It has just been marketed and the interest became fully liquid.

The Integrated Theory of Business Valuation

Next, let's address the question of marketability discounts for controlling interests from the viewpoint of the integrated theory of business valuation.

Any valuation discount represents differences in expected cash flow, growth, and risk between one conceptual level of value and another. For example, the marketability discount, or discount for lack of marketability, represents differences in expected cash flow, growth, and risk between the marketable minority/financial control level of value (V = CFe / (Re – Ge)). CFe represents the normalized expected cash flow of an enterprise (business), Ge represents the expected growth of that cash flow, and Re represents the risks associated with the business and achieving the expected cash flows. The familiar Gordon Model represents the value of a business at the marketable minority/financial control level of value.

The nonmarketable minority level of value can be represented conceptually by the equation (Vsh = CFsh / (Rhp – Gv)). Vsh is the nonmarketable minority level of value. CFsh is the expected cash flow to the shareholder of a subject illiquid minority interest. CFsh is almost always less than CFe because of reinvestments into a business or agency costs imposed by controlling shareholders. Gv is the expected growth in value of the illiquid minority interest over the expected holding period of the investment (including liquidity assumed at the marketable minority/financial control level of value. Rhp represents the risks associated with achieving CFsh, including growth, over the expected holding period of the investment.

Why does a marketability discount (or DLOM) exist?

- CFsh is most often less than CFe

- Gv may be less than Ge

- Rhp is almost certainly greater than Re

Recurring Mistaken Rationales for Marketability Discounts for Controlling Interests

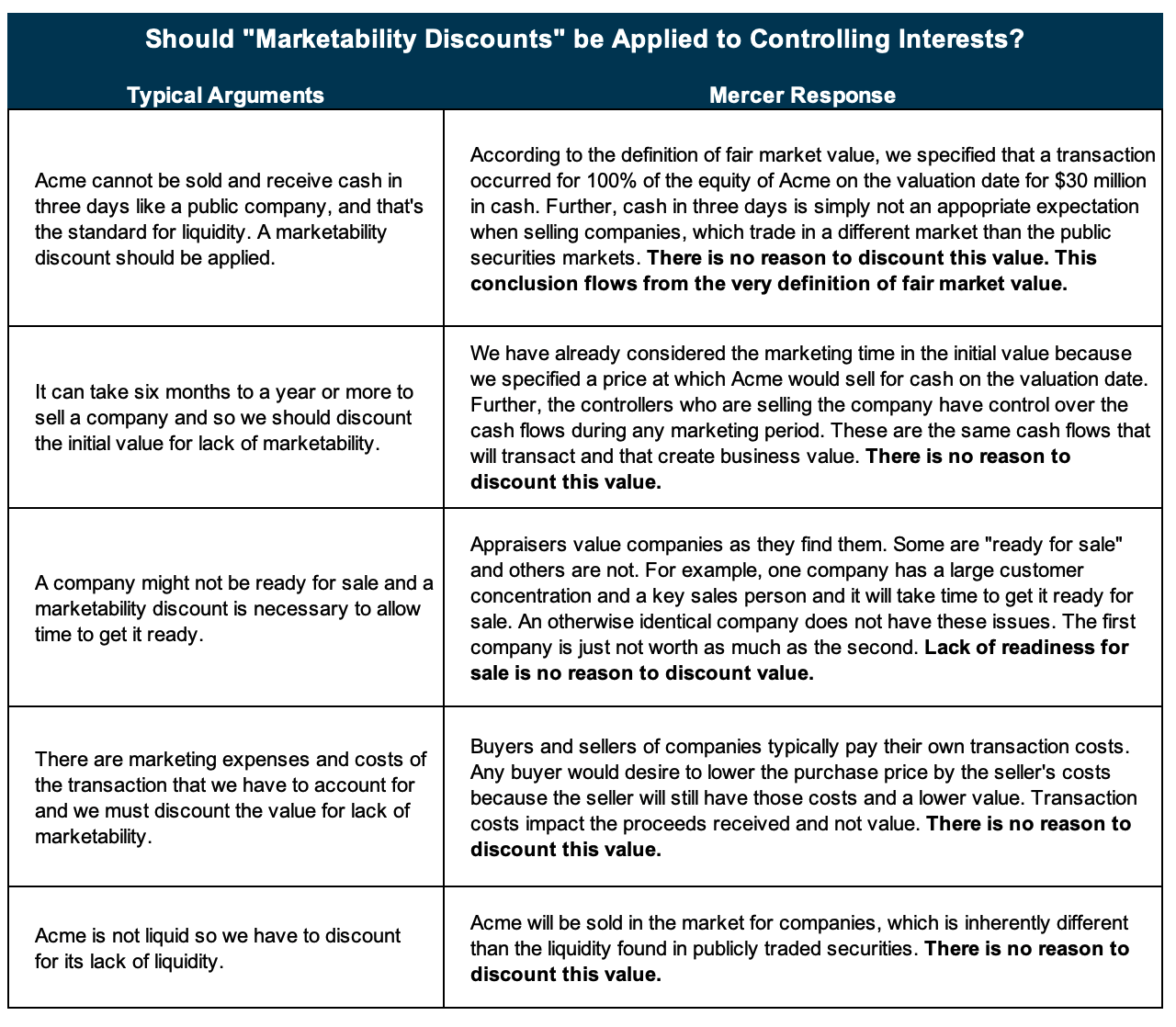

Let's take the analysis a bit further. Assume we have valued 100% of the equity of Acme Manufacturing, a manufacturer of parts for the automotive industry. The initial financial control/marketable minority value is $30 million. You as the other appraiser, and I agree that this is a reasonable value. The question now is whether a marketability discount should be applied. In the following figure some of the typical arguments for such a discount are addressed and we find that they are not correct or reasonable.

Conclusion

To those who would suggest that a controlling interest is "marketable and non-liquid" and therefore, a marketability discount for controlling interests should be applied, please articulate what that means in terms of expected cash flows, growth and the risks of achieving those cash flows. Differences in these factors are the only sources of valuation discounts (or premiums). It cannot be done, so those authors who try to create a fictional level of value are, in my opinion, simply wrong.