Is It Time to Eat the Golden Goose?

It was ten years ago in these very pages of Bank Watch that we wrote an article entitled “Is It Time for Banks to Rethink Insurance?” The year was 2014. Interest rates were near zero, the S&P 500 was in the neighborhood of 1,600, and Bitcoin finished the year at a mere $300.

The narrative at the time was that the lingering effects of the great recession, higher capital requirements for banks, and frothy valuations for insurance agencies driven by private equity bidders had firmly crowded out the banks from the agency M&A market. Indeed, bank acquisitions of insurance agencies had been declining for several years at that point. We suggested at the time that banks could still benefit from the recurring revenue stream offered by an insurance subsidiary, not to mention the higher growth and diversification in non-interest income.

In the decade since, a few banks did invest in their insurance agency operations, though mostly through organic means as opposed to M&A. At the same time, market multiples and private equity’s appetite for insurance agencies only increased. The net effect has led to some very favorable outcomes for banks willing to part with their insurance units.

Just last month, Trustmark (TRMK) announced an agreement to sell Fisher Brown Bottrell Insurance to Marsh McLennan Agency for approximately $316 million in cash, resulting in after-tax proceeds to TRMK of $228 million. The reported deal value implies a multiple of 5.4x revenue, 18.6x earnings-before-interest-taxes-depreciation-and-amortization (EBITDA), and 25.7x net income. TRMK intends to use proceeds from the deal to reposition lower-yielding securities to higher-yielding, market-rate securities, and meaningfully improve its capital ratios.

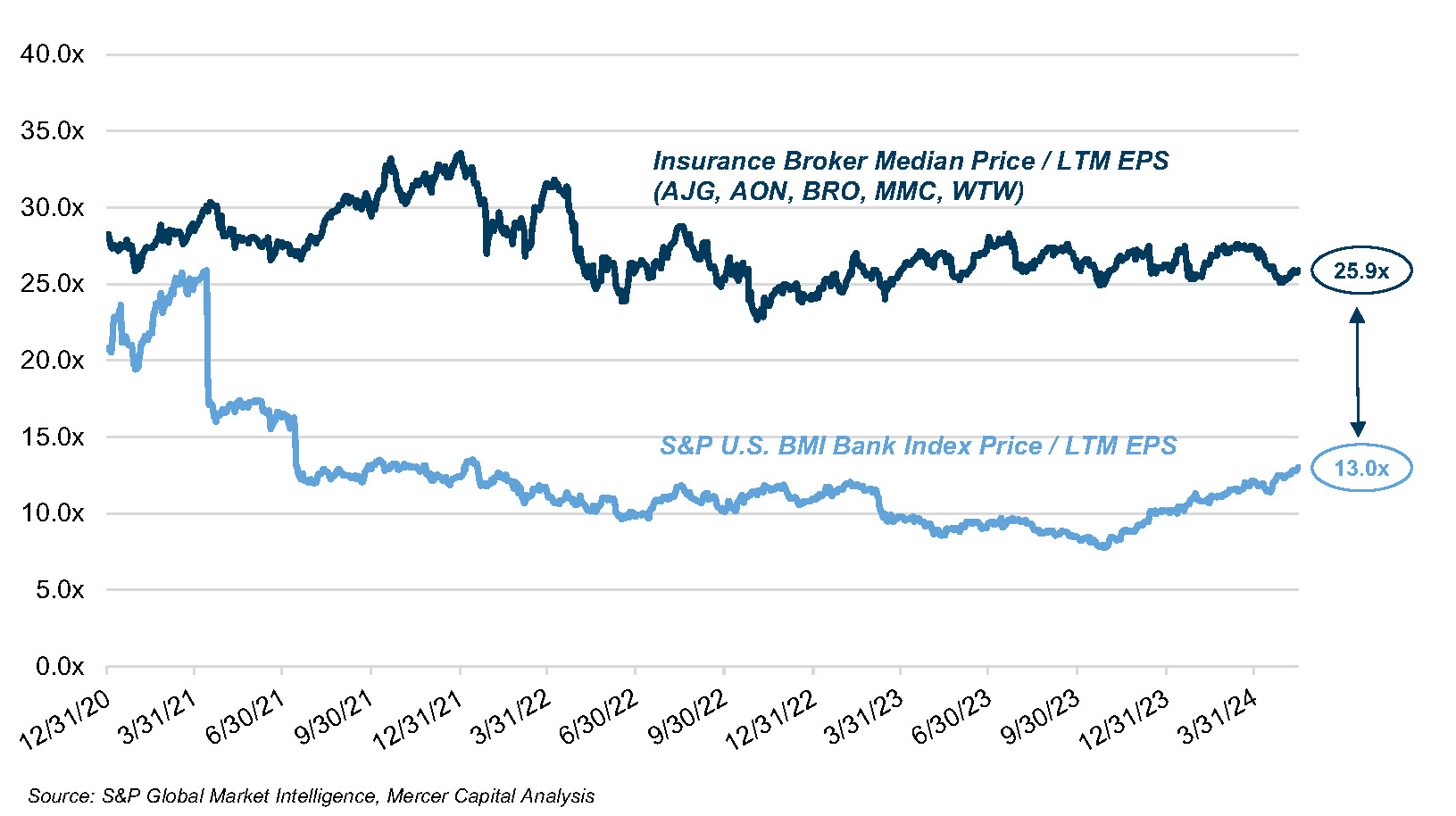

So how did we get to this point? And what is the next step in this cycle? As shown in Exhibit 1, the differential between PE multiples for banks and insurance brokers has been widening for several years. Part of this is attributable to market dynamics and interest rates, leading to lower returns (and expectations) for banks when compared to public insurance brokers.

Through mid-May 2024, the median PE multiple for the public insurance broker group was 25.9x, which is roughly double that of the S&P U.S. BMI Bank Index at 13.0x. Thus, it would only be natural for a bank with a significant insurance operation to wonder if the value realization of a dollar of insurance income would be better captured outside the bank’s typical pricing multiples.

Exhibit 1: PE Multiple Differential Between Banks and Insurance Brokers

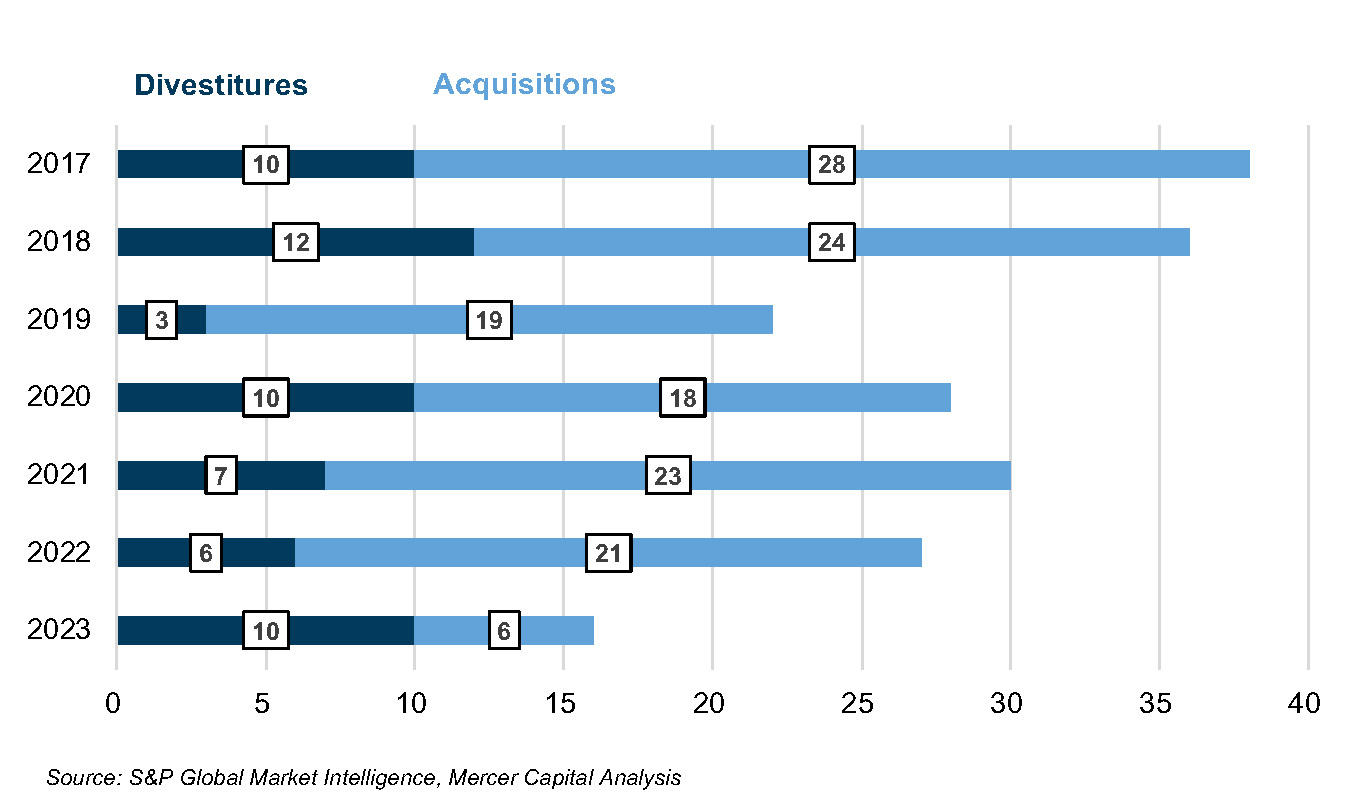

This arbitrage of earnings multiples has undoubtedly influenced many sellers of bank-owned agencies in recent years. As observed by S&P Global Market Intelligence, 2023 marked the first time in at least eight years that U.S. banks divested more insurance agencies than they acquired (see Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Bank Divestitures and Acquisitions of Insurance Agencies

The strategic rationale behind the latest group of divestitures has been largely consistent. Capitalizing on the sale of an insurance subsidiary at a favorable valuation provides several benefits, potentially including:

- Capital redeployment from lower-yielding to higher-yielding securities;

- The ability to offset losses from bond portfolio repositioning with the gain on the insurance unit sale;

- Enhancements to capital ratios;

- Tangible book value per share accretion; and,

- Additional support and focus for the core banking business.

In certain circumstances, the driving force behind a transaction might be the strategic imperative of a particular acquirer (such as the desire to bolster presence in a geographic market or to double down on a particular line of business).

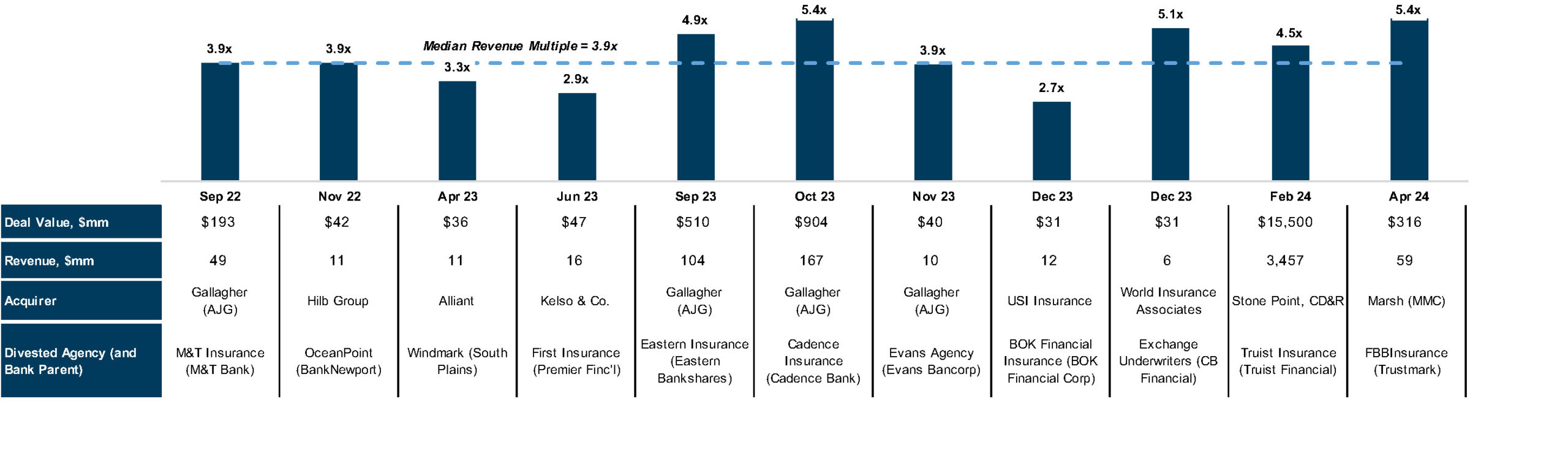

Exhibit 3: Revenue Multiples for Select Bank / Insurance Agency Divestitures Since 2022

Click here to expand the image above

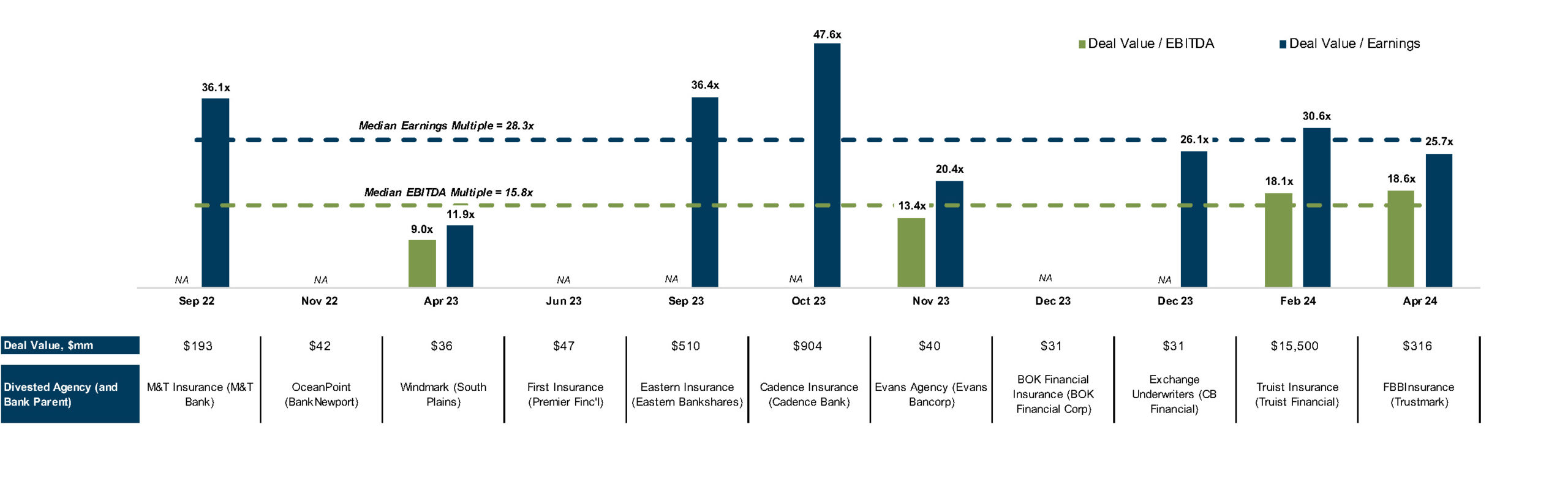

Exhibit 4: Earnings and EBITDA Multiples for Select Bank / Insurance Agency Divestitures Since 2022

Click here to expand the image above

On Exhibit 3, we have summarized the revenue multiples and other metrics for select insurance agency divestitures since 2022. Six of the eleven agencies had insurance revenue of under $20 million. At the other end of the spectrum, Truist’s sale of its insurance division to private equity buyers Stone Point and CD&R is one of the largest insurance brokerage transactions of all time (and was achieved in 20% and 80% stages). Public acquirer Arthur J. Gallagher & Co. has been the most prolific bank agency acquirer, inking large deals for M&T Insurance, Eastern Insurance, and Cadence Insurance.

One interesting observation is that the price paid as a multiple of insurance revenue is only loosely correlated with size. The median revenue multiple for the group is 3.9x.

Exhibit 4 presents the earnings multiples (where available) for the same group of agency transactions. Obviously, not all buyers/sellers choose to disclose earnings multiples and not all of the bank sellers report segment-level financial statements for their insurance subsidiaries. Further, transactions in the insurance brokerage industry are often struck on the basis of pro forma earnings (or EBITDA) to the buyer.

It is likely that these buyers (most of whom are either strategic or private equity sponsored consolidators) would anticipate a modest amount of add-backs for reduced back-office expenses and other industry synergies. While there is greater dispersion in these observations, the median EBITDA and earnings multiples for the group are 15.8x and 28.3x, respectively.

So are bank acquisitions of insurance agencies a thing of the past now? Not necessarily. Hindsight is always 20/20. Perhaps banks should have pushed back against the private equity buyers over the last decade and been willing to bid higher on acquisitions. In retrospect, paying 8x or 10x or even 12x EBITDA for a small insurance agency doesn’t seem that crazy when the consolidated unit can now be monetized at 15x.

Often, the best determinant of total return in an M&A deal is entry price, and so if a bank has the ability to source proprietary off-market agencies or books of business through local connections, that strategy is still well worth considering.

What about banks that already have an insurance subsidiary? What steps should you take? Here are a few suggestions:

- Conduct a strategic evaluation of the agency in the context of the bank’s overall strategy. Does the agency fit into the long-term vision of the bank? Is the sum of the parts greater than the whole?

- What is the agency’s true earning power or valuation as a stand-alone entiy? Consider obtaining an independent valuation or Quality of Earnings study to analyze the financials, ask the difficult questions, and examine the business in the way that a potential acquirer would.

- If sale is a possibility, is the business actually ready for sale? Is the corporate structure clean or messy? Do you have a collection of third-party producer arrangements that need to be consolidated? Are there minority owners? How does the expense allocation and/or resource sharing between the bank and agency work?

- Do you have alignment between the agency and bank management? Are there separate boards? Intertwined management and/or ownership? Would a sale create potential issues of conflict or necessitate a fairness opinion?

Even if all the other boxes are checked, is selling the bank’s agency that took 20 years to build the right long-term move? Maybe. Is it shortsighted to sell off the golden goose agency in the name of “balance sheet repositioning”? Maybe not. Every situation and every transaction is unique. Clearly, the banking and insurance industries are at an interesting place right now – and if you are a participant in both then you have a few options to consider.

If you have questions about these topics or would like to discuss a situation in confidence, please contact a Mercer Capital professional.