A Matter of Life (Insurance) and Death

A buy-sell agreement among family shareholders should provide clear instructions for how the company’s stock is to be valued upon the occurrence of a triggering event, such as the departure or death of a shareholder. The United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit recently heard Thomas A. Connelly, in his Capacity as Executor of the Estate of Michael P. Connelly, Sr., Plaintiff-Appellant v. United States of America, Department of Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, Defendant-Appellee. The Eighth Circuit court affirmed a district court decision that concluded that life insurance proceeds received by a company triggered by a shareholder’s death should be included in the valuation of the company for estate tax purposes.[1]

Connelly is an estate tax deficiency case dominated by two themes: (i) the treatment of life insurance in the valuation of stock of a private company when a shareholder dies and (ii) the consequences of executing a buy-sell agreement that fails to meet the requirements under the Internal Revenue Code, Treasury regulations, and applicable case law, for purposes of controlling the valuation of a closely held company.[2] Using Connelly as a backdrop, we first demonstrate how opposing applications of life insurance proceeds received upon the death of a shareholder impact a company valuation. We then offer observations from a study of the Connelly buy-sell agreement from a valuation perspective that private business owners and their advisors should mind when drafting, reviewing, and amending buy-sell agreements.

The Stock Purchase Agreement

Crown C Supply Company, Inc. is a roofing and siding materials company founded in 1976 and headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri.[3] Crown C (an S corporation) and brothers Michael, Thomas, and Mark Connelly originally entered into a stock purchase agreement (“SPA”) on January 1, 1983. Mark’s interest in Crown C was terminated prior to the stock purchase agreement being amended and restated on August 29, 2001.[4] Crown C had 500 shares of common stock at the date of the SPA’s execution. Michael, via a trust, owned 385.9 shares of Crown C stock representing a 77.18% ownership interest. Thomas, individually, owned the remaining 114.1 shares representing a 22.82% ownership interest.

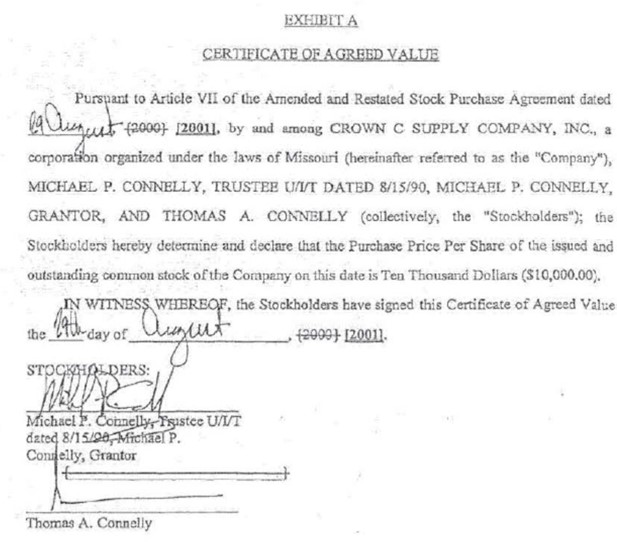

Pursuant to the terms of the SPA, Michael and Thomas executed a certificate of agreed value that set the purchase price of Crown C’s stock upon a triggering event at $10,000 per share (see graphic below). Based on this purchase price per share, which disregarded accepted valuation principles and methodologies, the implied aggregate market value of the company’s stock on August 29, 2001, was $5.0 million.

Therefore, at that date, Michael’s shares would have had an agreed value of approximately $3.9 million, while Thomas’s shares would have had an agreed value of approximately $1.1 million. In July 2009, with no update to the agreed value of the company’s equity, Crown C purchased life insurance policies on both Michael’s and Thomas’s lives in the amount of $3.5 million each. The rationale for purchasing the same amount of life insurance on each brother’s life when one brother’s ownership interest was approximately 3.4x larger than the other brother’s is unclear. The SPA dictatedthat life insurance proceeds were to be used to redeem a deceased shareholder’s interest.

The Sale and Purchase Agreement

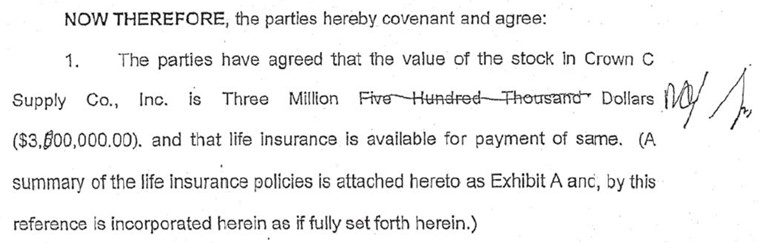

Michael, who served as Crown C’s president and CEO, died on October 1, 2013. Thomas was the executor of Michael’s estate. Effective November 13, 2013, Thomas, as trustee of Michael’s trust and a second trust for Molly C. Connelly, Michael’s daughter, recused himself from “all matters touching upon the sale, pricing, negotiation, and transaction of any sale of the stock of Michael P. Connelly, Sr.’s interest in Crown C Supply Company, Inc.”[5] Had Thomas not recused himself he would have been in the conflicted position of negotiating on behalf of Michael’s estate with the company, of which he was now the sole surviving shareholder. Effective the same date, Thomas and Michael’s son, Michael P. Connelly, Jr., executed a sale and purchase agreement governing the redemption of the estate’s shares in Crown C as well as in other entities.[6] Thomas (representing Crown C) and Michael Jr. (representing Michael Sr.’s estate) agreed, without relying upon a formal valuation, to a purchase price of $3.0 million for the estate’s shares (see graphic below).

The estate noted, however, that the $3.0 million purchase price “resulted from extensive analysis of Crown C’s books and the proper valuation of assets and liabilities of the company. Thomas Connelly, as an experienced businessman extremely acquainted with Crown C’s finances, was able to ensure an accurate appraisal of the shares.[7] I’ll discuss the importance of engaging a qualified appraiser in matters such as these below.

The Estate’s Argument: Life Insurance Proceeds Are Not a Corporate Asset

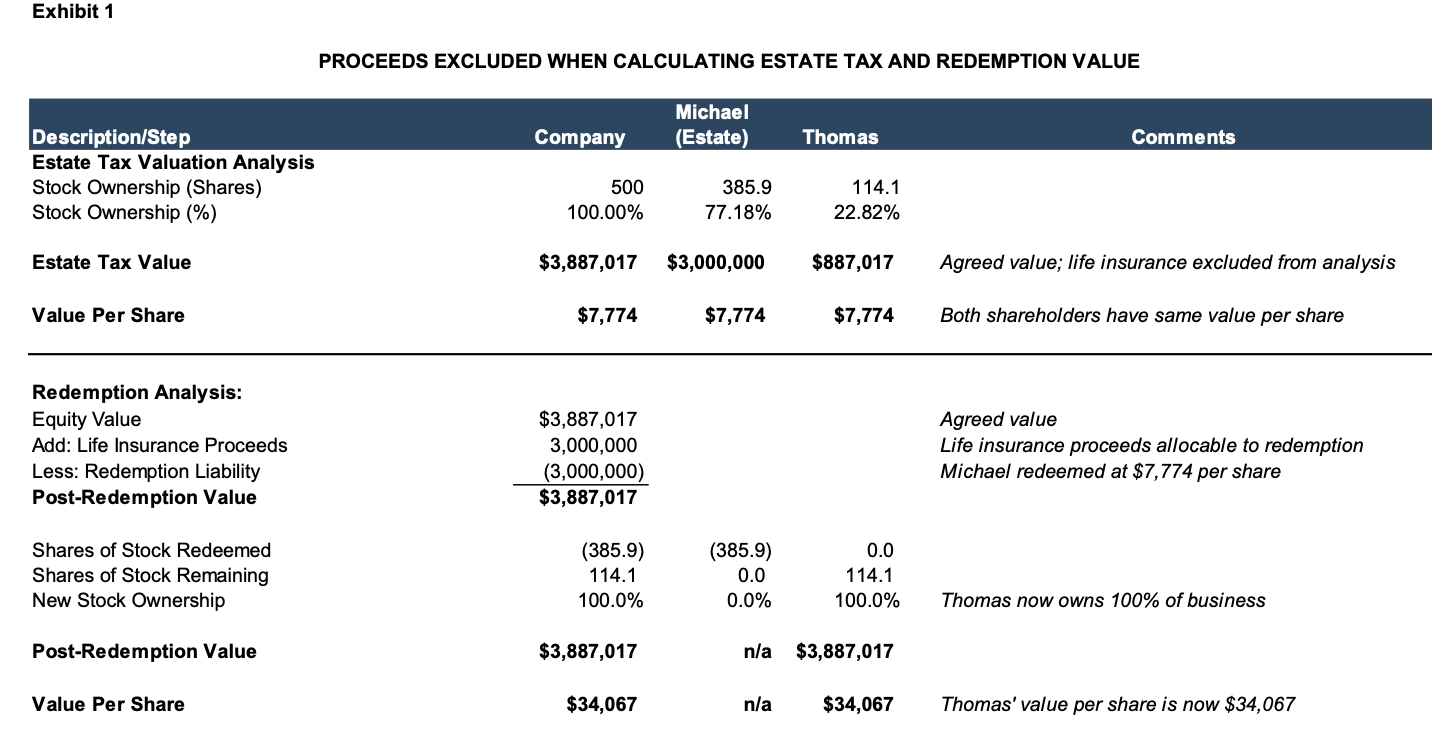

Crown C received $3.5 million in life insurance proceeds upon Michael’s death. Crown C immediately recognized a corporate redemption liability and used $3.0 million of the life insurance proceeds to redeem the estate’s interest in Crown C. It is interesting to note from the graphic above that Michael’s estate’s interest originally was equal to the total cash value of the life insurance proceeds, but at some point was reduced by $500,000 because the company needed additional funding.[8] Exhibit 1 demonstrates this narrative.

(click here to expand the figure above)

Key takeaways from this scenario:

One would expect to see a “top-down” valuation methodology in which the value of 100% of Crown C’s equity is established first, followed by the determination of value attributable to the estate’s shares. However, the aggregate value of Crown C’s equity of $3.9 million was implied based on the value of the estate’s interest of $3.0 million.

Crown C immediately recognizes a redemption liability equal to $3.0 million in life insurance proceeds and pays $3.0 million to Michael’s estate in exchange for redeeming the estate’s 385.9 shares; Michael’s estate is redeemed at $7,774 per share.[9]

Post-redemption, the total value of the company’s equity does not change while the share count decreases from 500 shares to 114.1 shares, all owned by Thomas.

Thomas now owns 100% of the company at a value of $34,067 per share,[10] which is approximately 4.4x the value at which Michael’s estate was redeemed. The value of Thomas’s ownership interest increased by 338% with no additional investment.

The IRS’ Argument: Life Insurance Proceeds Are a Corporate Asset

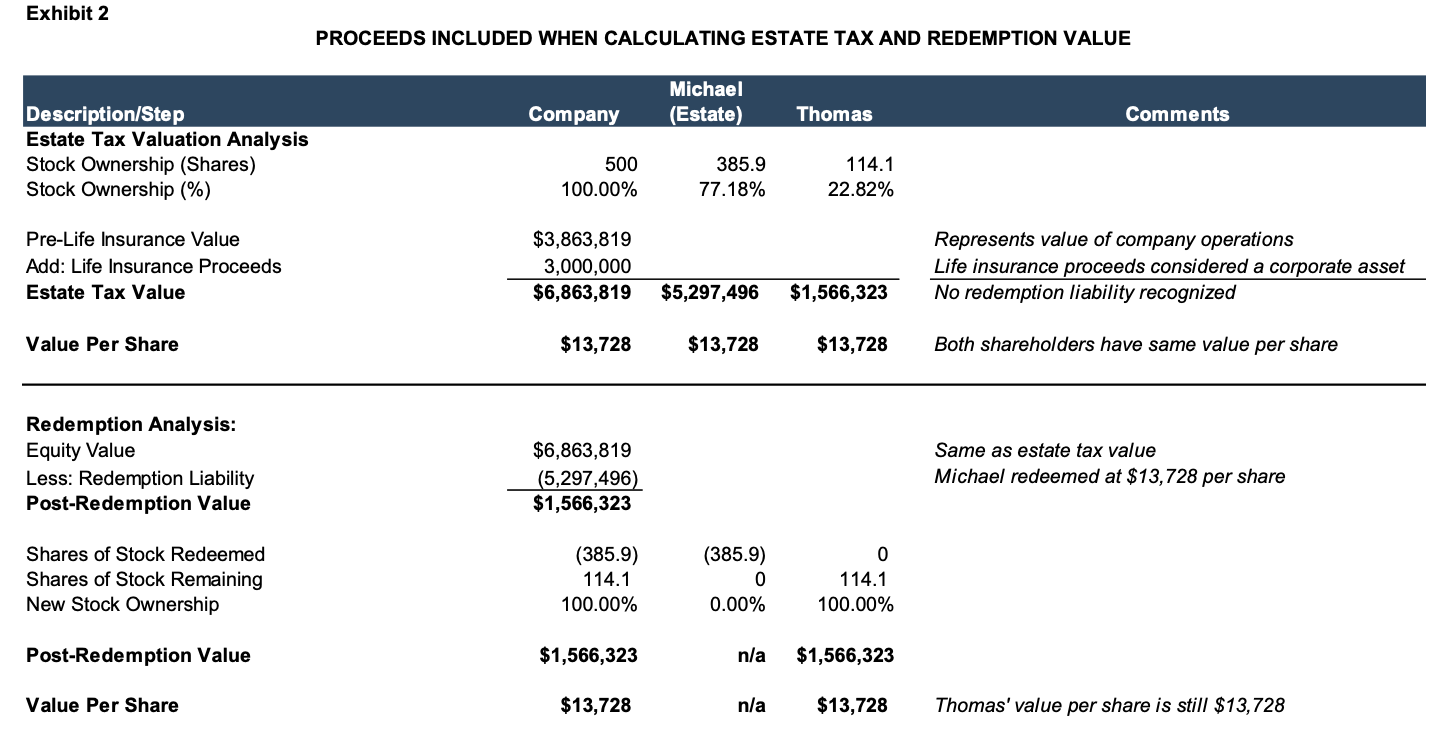

The IRS saw things differently, arguing that the insurance proceeds should be included in Crown C’s equity value. See Exhibit 2 below.

(click here to expand the figure above)

Key takeaways from this scenario:

The equity value of the business for estate tax purposes was $6.9 million inclusive of the $3.0 million in life insurance proceeds. The IRS did not include the excess $500,000 of life insurance in its valuation.

The resulting value per share is $13,728[11].

The estate’s 385.9 shares have a total value of $5.3 million and Michael’s estate is redeemed at $13,728 per share, reducing the company’s equity value to $1,566,323.

Post-redemption, the share count decreases from 500 shares to 114.1 shares, all owned by Thomas at a value of $13,728 per share, which is equal to the pre-redemption value per share.

As the life insurance proceeds utilized only totaled $3.0 million, the redemption liability of $5.3 million would have been underfunded by approximately $2.3 million, leaving the company (in this case, solely Thomas) on the hook to finance the shortfall.

The Funding Mechanism Dilemma

It should be obvious that the manner in which life insurance proceeds are treated can have a dramatic impact on the selling shareholder, the remaining shareholders, and the company’s ability to buyout the selling shareholder. In one scenario, the estate is redeemed relative to a windfall received by the surviving shareholder. In the second scenario, the estate is redeemed at a higher value, but to the detriment of the company most likely having to finance a portion of the buyout. So, what is the fair way to treat life insurance in this situation? Ultimately, the parties to the buy-sell agreement decide what is fair with the help of their legal and other professional advisors, but such a decision must be addressed directly and without vagueness in the buy-sell agreement.

The Defining Elements of a Valuation Process Agreement

We now turn to observations of the Connelly SPA itself from a valuation perspective. Valuation process agreements such as the Connelly SPA have six defining elements:[12] (i) standard of value; (ii) level of value; (iii) the “as of” date; (iv) qualifications of the appraiser; (v) appraisal standards; and (vi) funding mechanisms. The first five elements are required to specify an appraisal that is consistent with prevailing business appraisal standards. We’ve seen how the Connelly SPA addressed element #6, funding mechanisms. So, how, then, does the Connelly SPA stack up regarding defining elements #1 through #5?

Standard of Value

Per the American Society of Appraisers ASA Business Valuation Standards, the standard of value is “the identification of the type of value being used in a specific engagement; e.g. fair market value, fair value, investment value.”[13]

Fair market value, the standard that applies to nearly all federal and estate tax valuation matters and which is specified in most buy-sell agreements, is referenced in the Connelly SPA as part of the definition of appraised value per share. Fair market value itself, however, is not defined in the SPA. Without a specific, clear definition of fair market value, such as that from the ASA Business Valuation Standards or the Internal Revenue Code, the interpretation of fair market value is left to the appraiser(s). In the Connelly matter, upon a triggering event two appraisers were to be engaged (one by Crown C and one by the selling shareholder). Should the opinions of these two appraisers diverge by more than 10% of the lower appraised value, a third appraiser could have been engaged. The SPA as drafted opens the door for three interpretations of fair market value. And with multiple interpretations comes the increased likelihood of litigation.

Level of Value

Valuation theory suggests that there are various “levels” of value applicable to a business or business ownership interest. The graphic below depicts these levels. A formal business valuation for gift and estate tax purposes will clearly state the level of value, and therefore, no interpretation is needed as to the applicability of control premiums or discounts for lack of control and lack of marketability.

Per the Connelly SPA, in the scenario in which appraisers are utilized in lieu of issuing a certificate of agreed value, “the appraisers shall not take into consideration premiums or minority discounts in determining their respective appraisal values.” In the absence of minority interest discounts, Thomas’s minority interest (22.82%) would have been valued on a pro-rata basis relative to Crown C’s total value.

The As-Of Date

Every appraisal has an “as-of” date, more commonly referred to as the valuation date. Why is the valuation date important? Business appraisers rely upon information that was “known or reasonably knowable” on the valuation date. For purposes of filing Form 706, the valuation date is the date of death (estates may elect the alternate date, six months from the date of death, as the valuation date). For redemption purposes, however, the Connelly SPA refers to “Appraisal Date,” which is “the date an option is exercised or a mandatory purchase is required.” As such, the Connelly SPA does allow for a redemption to occur on a specific date.

Qualifications of Appraisers

If the qualifications of an appraiser are not specified, just about anyone can do the appraisal. The Connelly SPA mentions that an appraiser “shall have at least five years of experience in appraising businesses similar to the Company.” That’s it. The SPA makes no mention of formal education, valuation credentials such as ASA, ABV, or CVA, or continuing education and training requirements. Ultimately, this was a moot point for Connelly because no appraiser was ever hired to do a valuation. But what could happen if an unqualified appraiser is hired to perform a valuation? A recent tax court case, Estate of Scott M. Hoensheid, deceased, Anne M. Hoensheid, Personal Representative, and Anne M. Hoensheid, Petitioners, v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue Service, Respondent (T.C. Memo 2023-34), addressed this situation head-on. While the case was related to the donation of closely held stock, not using a qualified appraiser had a damaging impact on the taxpayer. The company whose shares were subject to the charitable gift had been marketed for sale by an investment banker prior to the gift. The taxpayer’s attorney suggested that the investment banker be considered to do the appraisal for the gifting because "since they have the numbers, it would seem to be the most efficient method."[14] In court, the petitioners argued that the investment banker was qualified because he had prepared "dozens of business valuations" over the course of his 20+ year career as an investment banker. According to the court, an individual’s “mere familiarity with the type of property being valued does not by itself make him qualified.” The court further noted that the investment banker “does not have appraisal certifications and does not hold himself out as an appraiser.” The court relied on testimony at trial about appraisal experience to be instructive, as the investment banker testified that he conducted valuations "briefly" and only "on a limited basis" before starting at the investment bank the year before the appraisal. The investment banker also testified that he performed (presumably at no charge) business valuations for prospective clients "once or twice a year" in order to solicit their business. The court found the investment banker’s “uncontroverted testimony sufficient to establish that he does not regularly perform appraisals for which [he] receives compensation." The end result for the taxpayer in Hoensheid: the Tax Court found that the taxpayer failed to comply with the qualified appraisal requirements and denied the charitable deduction.

Appraisal Standards

Occasionally, buy-sell agreements lay out the specific business appraisal standards to be followed by the appraiser. Standards most often cited in buy-sell agreements are the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (commonly referred to as “USPAP”), the ASA Business Valuation Standards, AICPA’s Statement on Standards for Valuation Services No. 1 (commonly referred to “SSVS”) and NACVA’s Professional Standards. The Connelly SPA did not reference any of these standards. Without any appraisal standards referenced, any appraiser elected to perform a valuation under the SPA who was not a member of one of the national appraisal organizations has no requirement to follow any set of standards or code of ethics.

Tax Court Conclusions

Connelly was first decided by the District Court in September 2021. Having been appealed by the estate, the Eighth Circuit affirmed the District Court’s decision in June 2023. The District Court Decision The IRS had contended that the life insurance proceeds should be included in the valuation of Crown C’s equity. The estate argued that the redemption obligation was a corporate liability that offset the life insurance proceeds dollar for dollar. The District Court sided with the IRS, noting that “Because the insurance proceeds are not offset by Crown C's obligation to redeem Michael's shares, the fair market value of Crown C at the date of date of death and of Michael's shares includes all of the insurance proceeds.”[15]

The Circuit Court Decision

The Circuit Court affirmed the District Court’s decision, noting “In sum, the brothers’ arrangement had nothing to do with corporate liabilities. The proceeds were simply an asset that increased shareholders’ equity. A fair market value of Michael’s shares must account for that reality.”[16]

Current Status

Shareholder buyouts often occur at inconvenient times, and poor planning can have financially devastating consequences. In Connelly, a poorly drafted buy-sell agreement resulted in a notice of deficiency from the IRS in the amount of $998,155 [17] and undisclosed legal and professional fees incurred to litigate the matter. The estate has sought a refund of $1,027,042 that it views was “erroneously, illegally, and excessively assessed against and/or collected from Plaintiff as federal estate tax…”[18] In August 2023, counsel for the estate filed with the Supreme Court of the United States a petition for a writ of certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eight Circuit. On December 13, 2023, the Supreme Court granted the petition for writ of certiorari, signifying its acceptance of the case for review. As of February 2024, the case had not yet been set for argument.

[1] Courts have had differing opinions on the life insurance/valuation matter. In Estate of George C. Blount, Deceased, Fred B. Aftergut, Executor, v. Commissioner, the United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh Circuit ruled that life insurance proceeds used to redeem a stockholder’s shares do not count towards the fair market value of the company when valuing those same shares.

[2] The buy-sell agreement that is the subject of Connelly was challenged by the IRS as invalid for controlling the valuation of the subject company’s stock in an estate tax scenario. The district and circuit courts both agreed and deemed the buy-sell agreement invalid.

[3] Crown C was sold to SRS Distribution, Inc., a portfolio company of Leonard Green & Partners and Berkshire Partners, in 2018. Terms of the deal were not disclosed. Crown C continued to serve the St. Louis market as of the publication date of this article.

[4] Amended and restated stock purchase agreement by and among Michael P. Connelly, trustee U/I/T dated 8/15/90, Michael P. Connelly, grantor, and Thomas A. Connelly, executed effective August 29, 2001.

[5] Sale and purchase agreement by and among Thomas A. Connelly, trustee of The Michael Connelly Irrevocable Trust dated 15 August 1990, Crown C Supply Co., Inc., a Missouri Corporation, Thomas A. Connelly, individually, Connelly Partnership/Connelly, LLC, and 5200 Manchester, LLC, executed November 13, 2013.

[6] Ibid.

[7]Connelly v. United States, Memorandum and Order, page 21, September 2021.

[8] Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri – St. Louis, No. 21-3683, page 3, filed June 2, 2023.

[9] ($3.0 million / 385.9 shares) = $7,774 / share.

[10] ($3.9 million / 114.1 shares) = $34,067 per share.

[11] ($6.9 million / 500 shares)

[12] Mercer, Z. Christopher, Buy-Sell Agreements for Closely Held and Family Business Owners (Peabody Publishing LP, 2010).

[13] American Society of Appraisers Business Valuation Standards (approved through November 2009).

[14] T.C. Memo. 2023-34; Estate of Scott M. Hoensheid, deceased, Anne M. Hoensheid, Personal Representative, and Anne M. Hoensheid, Petitioners, v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue Service, Respondent.

[15] Connelly v. United States, Memorandum and Order, page 35, September 2021.

[16] Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri – St. Louis, No. 21-3683, page 13, filed June 2, 2023

[17] Complaint of Thomas A. Connelly, Executor of the Estate of Michael P. Connelly, Sr. dated May 23, 2019.

[18] Ibid.

Originally published in Mercer Capital's Value Matters Newsletter: Q1 2024