LOV(E): What Are the “Levels of Value” and Why Does It Matter to Auto Dealers?

Part I

In the spirit of Valentine’s Day, we are covering a topic near and dear to the hearts of business valuation analysts. LOV – or “Levels of value” – refers to the idea that while “price” and “value” may be synonymous, they don’t quite mean the same thing.

This week, we reshare a prior post (originally published in February 2021) that is still relevant today.

Levels of Value Overview

Shareholders are occasionally perplexed by the fact that their shares can have more than one value. This multiplicity of values is not a conjuring trick on the part of business valuation experts but simply reflects the economic fact that different markets, different investors, and different expectations necessarily lead to different values.

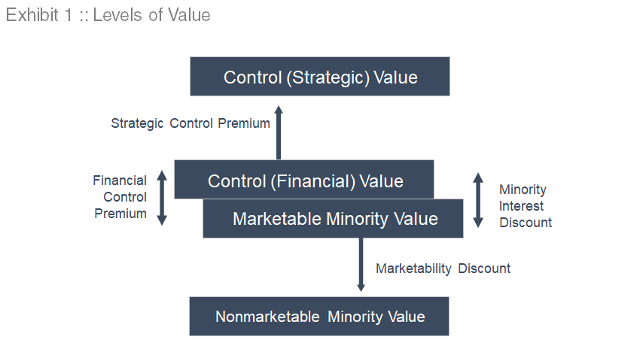

Business valuation experts use the term “level of value” to refer to these differing perspectives. As shown in Exhibit 1, there are three basic “levels” of value for a family business.

Each of the basic levels of value corresponds to different perspectives on the value of the business. Let’s explore the relevant characteristics of each level.

Marketable Minority Level of Value

The marketable minority value is a proxy for the value of your family business if its shares were publicly traded. In other words, if your family business joined the public ranks of Lithia, Sonic, Asbury, etc. through an IPO, what price would the shares trade at? To answer this question, we need to think about expectations for future cash flows and risk.

The marketable minority value is a proxy for the value of your family business if its shares were publicly traded.

- Expected cash flows. Investors in public companies are focused on the future cash flows that companies will generate. In other words, investors are constantly assessing how developments in the broader economy, the industry, and the company itself will influence the company’s ability to generate cash flow from its operations in the future.

- Public company investors have a lot of investment choices. There are thousands of different public companies, not to mention potential investments in bonds (government, municipal, or corporate), real estate, or other private investments. Public company investors are risk-averse, which just means that – when choosing between two investments having the same expected future cash flow – they will pay more today for the investment that is more certain. As a result, public company investors continuously evaluate the riskiness of a given public company against its peers and other alternative investments. When they perceive that the riskiness of an investment is increasing, the price will go down, and vice versa.

So, when a business appraiser estimates the value of your family business at the marketable minority level of value, they are focused on expected future cash flows and risk. They will estimate this value in two different ways.

When a business appraiser estimates the value of your business at the marketable minority level of value, they are focused on expected future cash flows and risk.

- Using an income approach, they create a forecast of future cash flows, and based on the perceived risk of the business, convert those cash flows to present value, or the value today of cash flows that will be received in the future.

- Using a market approach, they identify other public companies that are similar in some way to your family business. By observing how investors are valuing those “comps,” they estimate the value of the shares in your family business. Many novice investors are aware of Price-to-Earnings ratios, and there are plenty of valuation multiples that can be gleaned from public auto dealers.

While these are two distinct approaches, at the heart of each is an emphasis on the cash flow generating ability and risk of your family business.

We start with the marketable minority level of value because it is the traditional starting point for analyzing the other levels of value.

Control (Strategic) Level of Value

In contrast to public investors who buy small minority interests in companies, acquirers buy entire companies (or at least a large enough stake to exert control). Acquirers are often classified as either financial or strategic.

- Financially motivated acquirers often have cash flow expectations and risk assessments similar to those of public market investors. As a result, the control (financial) level of value is often not much different from the marketable minority level of value, as depicted in Exhibit 1. Imagine a private equity buyer with no other auto dealership investments. They’ll pay for the right to earn the cash flows you’ve been generating, but other than some creative financing, they may not be able to meaningfully increase cash flows above what the current dealer principal can achieve.

- Strategic acquirers, on the other hand, have existing operations in the same, or an adjacent industry. These acquirers typically plan to make operational changes to increase the expected cash flows of the business relative to stand-alone expectations (as if the company were publicly traded). For example, two adjacent auto dealers can likely run with a leaner management team.

Strategic acquirers may be willing to pay a premium to the marketable minority value if they can achieve revenue synergies but, given relationships with OEMs, there may be fewer synergies in automotive retail than some other industries.

The ability to reap cost savings or achieve revenue synergies by combining your family business with their existing operations means that strategic acquirers may be willing to pay a premium to the marketable minority value. However, given relationships with OEMs, there may be fewer synergies in automotive retail than some other industries.

Of course, selling your family business to a strategic acquirer means that your family business effectively ceases to exist. The name and branding may change, employees may be downsized, and production facilities may be closed. It also reduces a significant source of cash flow, as future earnings are accelerated to a lump sum payment up front. Many auto dealers have looked to exit with blue sky values high, but it’s also hard to walk away during a time of record profits in a business that can operate throughout the business cycle.

Nonmarketable Minority Level of Value

While strategic acquirers may be willing to pay a premium, the buyer of a minority interest in a family business that is not publicly traded will generally demand a discount to the marketable minority value. All else equal, investors prefer to have liquidity; when there is no ready market for an asset, the value is lower than it would be if an active market existed.

The buyer of a minority interest in a family business that is not publicly traded will generally demand a discount to the marketable minority value.

What factors are investors at the nonmarketable minority level of value most interested in? First, they care about the same factors as marketable minority investors: the cash-flow generating ability and risk profile of the family business. But nonmarketable investors have an additional set of concerns that influence the size of the discount from the marketable minority value.

- Expected holding period. Once an investor buys a minority interest in your family business, how long will they have to wait to sell the interest? The holding period for the investment will extend until (1) the shares are sold to another investor or (2) the shares are redeemed by the family business, or (3) the family business is sold. The longer an investor expects the holding period to be, the larger the discount to the marketable minority value. Imagine you own a 5% interest in a dealership that you’re looking to sell. If a potential buyer knows the dealer will “never sell to one of the big guys,” that will impact how much they’ll pay you for your interest.

- Expected capital appreciation. For most family businesses, there is an expectation that the value of the business will grow over time. Capital appreciation is ultimately a function of the investments made by the family business. Public company investors can generally assume that investments will be limited to projects that offer a sufficiently high risk-adjusted return. Family business shareholders, on the other hand, occasionally have to contend with management teams that hoard capital in low-yielding or non-operating assets, which reduces the expected capital appreciation for the shares. All else equal, the lower the expected capital appreciation, the larger the discount to the marketable minority value. Auto dealerships tend to have pretty strong cash flows, and relatively limited opportunities to reinvest in the business. While the OEM has imaging requirements every so often, the opportunity to meaningfully expand operations tends to be tied to adding on more rooftops.

- Interim distributions. Does your family business pay dividends? Interim distributions can be an important source of return during the expected holding period of uncertain duration. Interim distributions mitigate the marketability discount that would otherwise be applicable. High levels of distributions may be common for minority investors in auto dealerships. However, minority investors cannot compel these distributions themselves, and we’ve seen many cases where the cash simply builds on the balance sheet. As noted above, this can drag on returns.

- Holding period risk. Beyond the risks of the business itself, investors in minority shares of public companies bear additional risks reflecting the uncertainty of the factors noted above. As a result, they demand a premium return relative to the marketable minority level. The greater the perceived risk, the larger the marketability discount. A strong capacity for distributions and opportunities to be sold to a strategic buyer can push down marketability discounts for auto dealerships. Conversely, sporadic distributions and cash buildup can lower expected returns. And while dealerships must send monthly factory statements to the OEM, these don’t commonly get shared on a regular basis with minority investors who may not have a good pulse for how their dealerships are performing.

Conclusion

Your family business has a different value at each level of value because of differences in expected cash flows and risk factors. Hopefully, we’ve illustrated the “why” behind the various levels of value.

Next week we will cover why getting the Level of Value correct is so important, and discuss numerous instances where a dealer may encounter the value of their store from different levels.

Auto Dealer Valuation Insights

Auto Dealer Valuation Insights