In this two-part series (the first post dropped on Valentine’s Day), we are covering a topic near and dear to the hearts of business valuation analysts. LOV – or the “Levels of Value” – refers to the idea that while “price” and “value” may be synonymous, they don’t quite mean the same thing. A nonmarketable minority interest level of value is very different from a strategic control interest level of value.

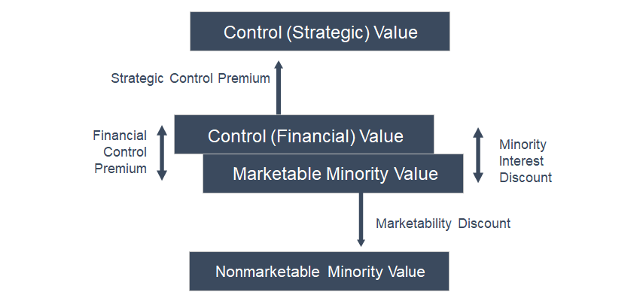

Part I of this two-part series described the Levels of Value and why the concept is so important to auto dealers. We present the Levels of Value chart below for reference.

This week, in part II of this series, we reshare a prior post (originally published in February 2021) and we discuss four potential transactions in which selecting the appropriate level of value is critical and explain why: 1) estate planning, 2) corporate development, 3) divestitures, and 4) shareholder redemptions.

Engagement administration and engagement planning are two steps in the valuation process that don’t garner much of the spotlight. However, defining the scope of the engagement is critical to the success of a valuation project. The scope and eventual engagement letter are often described as a road map for the project to follow. One of the great strengths of a family business is the ability to take the long view. Unburdened by the quarterly reporting cycles of publicly traded companies, family businesses can make investing and operating decisions for long-term benefit without worrying about the effect on the next quarter’s earnings. One of the foundations of this long-term perspective is the stability of ownership within the family. With an indefinite holding period, why does the value of the family business even matter? While the family may have an indefinite holding period, the fact of mortality means that individual shareholders do not. So, even for committed families, transactions will occur and valuations will matter. Let's consider four potential transactions in which selecting the appropriate level of value is critical.

1. Estate Planning

Many family shareholders determine that transferring wealth to heirs while still living is advantageous. Regardless of the specific technique used, the value of shares in the family business is a cornerstone of the estate planning process. Under the IRS’ definition of fair market value, the appropriate level of value depends on the attributes of the block of shares being transferred. Since estate planning almost always involves transactions of minority interests in the family business, the nonmarketable minority interest level of value is relevant.

There are also elements of estate planning that are unique to auto dealers. All dealerships must be operated by a Dealer Principal approved by the OEM. Any succession plan must consider whether the next generation would be approved as a Dealer Principal by the OEM. This approval is not always guaranteed. When desiring to transfer ownership to the next generation, dealers would be wise to consider a family choice that has been active in the dealership or has industry experience.

Any succession plan must consider whether the next generation would be approved as a Dealer Principal by the OEM.

Measuring the value of shares in the family business at the nonmarketable minority interest level of value is a two-step process. First, we consider what the shares would be worth if they were traded on an exchange (i.e., the marketable minority level of value). Second, we determine an appropriate discount to apply to that value to reflect the unfortunate side effects of owning a minority interest in a private company. The magnitude of that discount depends on factors like the expected duration of the holding period until a liquidity event, the level of interim distributions, and the expected pace of capital appreciation. When combined with an assessment of the risks facing the investor, these factors determine the marketability discount, which, in turn, defines the fair market value of the shares on a nonmarketable minority interest basis.

2. Corporate Development

Family businesses have two basic pathways for growth: organic growth through capital expenditures (“build”) or non-organic growth through acquisitions (“buy”). The pathways are not mutually exclusive. Some families are culturally averse to acquisitions, while for others a disciplined acquisition strategy is part of the family’s business DNA. As we have discussed in this space in prior blogs, the prospects for organic growth for dealers are somewhat constrained. While dealers can improve Fixed Operations and Used Vehicle Operations, they are limited to selling more vehicles from their OEM on the new vehicle side of operations. Those growth opportunities have been more constrained over the last two years due to inventory shortages and the microchip crisis. For more desired growth, dealers must consider adding additional rooftops or acquiring other dealerships.

For more desired growth, dealers must consider adding additional rooftops or acquiring other dealerships.

For family business acquirers, developing an appropriate valuation of the target is essential. As one of our colleagues is fond of saying: “Bought right, half right.” Regardless of the strategic merits of a proposed acquisition, the overpayment will weigh on the returns available to future generations of the family. When formulating a bid price for a potential target, acquirers should seek to answer two questions.

What is the business worth to the existing owners? Selling their business to you means that the existing owners will be giving up the future cash flows they expect the business to generate under their stewardship. This reflects the financial control level of value, which as we noted in last week’s post, is probably not much different from the marketable minority value.

What is the business worth to us? To answer this question, acquirers need to carefully evaluate how the target “fits” with their existing business. Will the combination of the two businesses generate revenue synergies (i.e., 2 + 2 = 5)? Or are there duplicative costs that can be eliminated as a means of generating higher margins for the combined entity? Perhaps the combination will reduce the risk of the family business, or perhaps the family has access to lower-cost capital than the existing owners. In any event, family business acquirers should develop forecasts for the pro forma combined entity using well-supported inputs that reflect the strategic case for the acquisition to determine what the business is worth to them. Forecasts are less seldomly used in the valuation of auto dealerships, but the concept of determining the anticipated future earnings is the same. Auto dealers will generally evaluate the last two to four years of operations to arrive at that conclusion. Due to heightened profitability over the last two years, this exercise can be more difficult. We are seeing many dealers consider an average of several years of operations as an indicator of expected future operations.

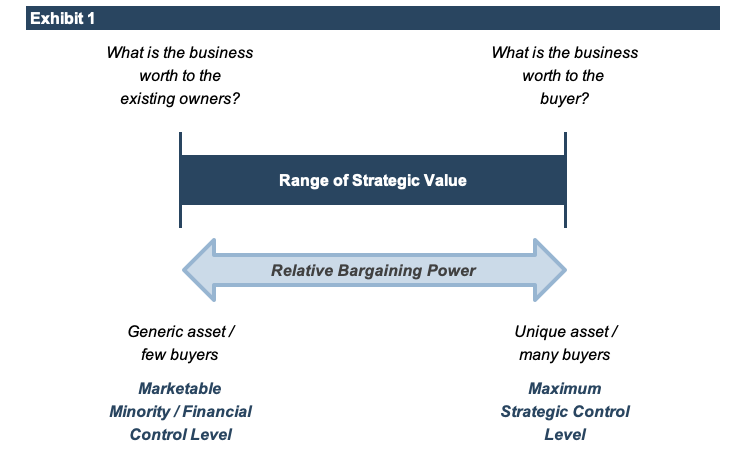

The difference between these two values defines the “space” over which negotiations will center. The ultimate purchase price will reflect the relative bargaining power of the two parties. As illustrated in Exhibit 1, bargaining power is a function of the number of likely buyers for the target, and whether the target represents a generic or unique opportunity for buyers.

To avoid overpaying, savvy family business acquirers focus not just on what the target could be worth to them, but also what the target is worth to its current owners, along with a careful assessment of the factors that influence the relative bargaining power of the parties.

3. Divestitures

At some point, many families transition to being enterprising families. In other words, they are defined by the fact that they pursue economic opportunities together, rather than by continued ownership of the legacy family business. In pursuit of broader portfolio management objectives, enterprising families may sell businesses from time to time. In this case, the dynamics described in the preceding section are reversed.

In the auto dealer space, we generally see divestitures occurring for one of two reasons in recent times. First, smaller single-point dealers are facing more pressures to compete against larger auto groups in terms of online platforms, imaging requirements, and the fear/threat of electric vehicles being introduced into their models. Secondly, dealers that do not have an identified succession plan or successor Dealer Principal candidates are apt to consider selling. Heightened profits and heightened blue sky valuation multiples are also making the decision to sell more attractive in the current environment.

As the seller, you won’t have direct access to what your business could be worth to the buyer. However, knowing how your industry is structured and how your business operates, you should be able to estimate potential revenue synergies and cost-saving opportunities available to the buyer.

In order to achieve a sales price closer to the value of your business to the buyer, it is important to identify the attributes of your business that differentiate it from other potential acquisition targets available to buyers. Further, generating interest from a larger pool of buyers is essential to reaping greater proceeds from a divestiture.

4. Shareholder Redemptions

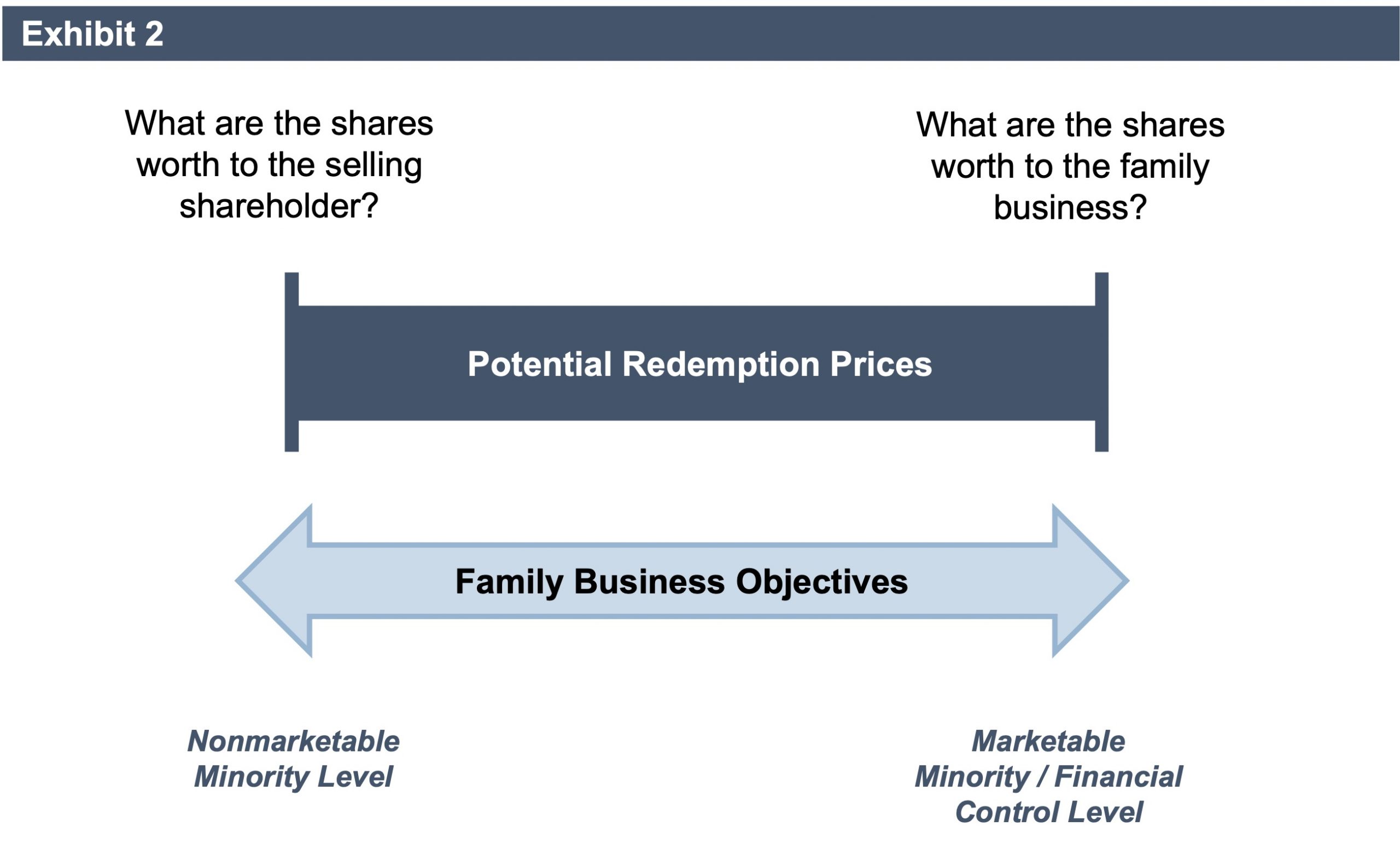

A shareholder redemption is a purchase by the family business of shares from a family shareholder. As with our corporate development and divestiture examples from last week’s post, shareholder redemptions reflect an inherent tension between buyers and sellers, as illustrated in Exhibit 2. Unfortunately, we often see these events occur in litigation because of the differing perspectives described below. It’s common for dealers to incentivize key employees and management with an ownership stake as part of an employment agreement. These ownership interests become the subject of redemption if the employee resigns or is terminated from the dealership.

In a shareholder redemption transaction, the buyer and seller do not share the same perspective.

In a shareholder redemption transaction, the buyer and seller do not share the same perspective.

The selling shareholder owns an illiquid minority interest in a private business. As a result, the fair market value – the amount that a hypothetical willing buyer would pay – reflects a marketability discount. In other words, the nonmarketable minority level is relevant.

However, in a shareholder redemption transaction, the buyer is not a hypothetical party, but the company that issued the shares in the first place. The family business is not burdened by the illiquidity of the shares in the same way a shareholder is. As a result, the value of the shares to the family business is consistent with the marketable minority level of value.

It strikes us as a bit perverse to evaluate transactions between family shareholders and family businesses in terms of relative negotiating leverage. Instead, we prefer to frame the decision in terms of family business objectives: What is the purpose of the redemption? The “correct” price at which to conduct a shareholder redemption transaction is always a bit ambiguous. Consider the alternatives:

Nonmarketable Minority Level. This seems straightforward – after all, that is the fair market value of what the shareholder owns. Why should the family business pay any more than that?

Marketable Minority Level. On the other hand, this is the value of what the redeeming company is acquiring. Why should the departing shareholder accept any less than that?

From an economic perspective, redemption at the nonmarketable minority level is accretive to the non-selling shareholders. Redeeming at the marketable minority level provides a windfall to the selling shareholder relative to the fair market value of their shares. There is no simple escape from this dilemma. The ambiguity around the level of value in these instances generally exists for engagements for internal and strategic planning purposes. If these events result in litigation, the levels of value are typically defined in the applicable standard of value or case laws of the jurisdiction governing the matter.

If the family business wants to discourage redemption requests, the nonmarketable minority level of value may be preferable.

If the family business is designing a shareholder liquidity program with a view to promoting positive shareholder engagement, it may be desirable to conduct redemptions at the marketable minority level of value. However, in such cases it is essential to set limits on the amount of redemption requests the family business will honor in a given period; otherwise, the liquidity program could trigger a “run on the bank,” crowding out corporate investments critical to the long-term sustainability of the family business.

If the objective of the redemption is to “prune” the family tree of unwanted branches, it may be necessary to pay a redemption price at the marketable minority / financial control level of value. Depending on state statute, it may be a legal necessity. In any event, the departing shareholders are likely to demand such pricing to exit the family business.

Conclusion

Your family business has a different value at each level of value because of differences in expected cash flows and risk factors. Considering four common corporate transactions, we have illustrated why the level of value matters to family businesses:

When transferring minority interests among family members in furtherance of estate planning objectives, the fair market value of the interests transferred is properly measured at the nonmarketable minority level.

When considering a potential acquisition, family businesses should evaluate both the marketable minority / financial control level of value (what the target is worth to the existing owners) and the potential strategic control level of value (what the target is worth to the family business). These two values for the target define the relevant range for negotiating a transaction price.

When divesting a business, the dynamics are reversed. The relevant negotiating range is set by the difference between the marketable minority / financial control level of value (in this case, what the business is worth to the family) and the strategic control level of value (what the business is potentially worth to the buyer). The family can improve its negotiating leverage in these situations by differentiating the business from other available targets and exposing the business to multiple motivated buyers.

Finally, shareholder redemptions can occur at either the nonmarketable minority or marketable minority /financial control levels of value. The appropriate level for a given transaction should be selected with a view to the objectives of the redemption for the family business.

These transactions can have profound and long-lasting economic implications for the family business and its shareholders. When the stakes are high, it’s a good idea to measure twice and cut once. When your dealership is preparing for any of these transactions, give one of our valuation professionals a call.