The Future of Auto Dealerships

How Inventory Shortages and Electric Vehicles May Shape the Future of Automotive Retail

Just as December is a good time to look back and reflect, January is a good time to look forward, to 2022 and beyond. When we value auto dealerships, we look back at performance in prior years because this helps to inform reasonable expectations for future performance. Prior to the pandemic, the directly preceding twelve months of performance may have been a reasonable proxy for ongoing expectations. However, throughout 2020 and 2021, discussions about when things will return to “normal” or whether we’re in the “new normal” have taken center stage.

In order to look forward, we must also consider the past, or as Shakespeare’s Antonio would say, “What is past is prologue.” In this post, we look at two key trends in 2021 (inventory shortages and electric vehicles/direct selling) and how they may inform how automotive retailing will look in the future.

Inventory Shortages

In case you’ve been living under a rock (or working from home and refusing to turn on the news), new vehicle inventory has been tight, reducing availability and raising prices. While a lack of necessary microchips has stolen headlines, general supply chain issues are also at play (labor shortages, plant shutdowns due to COVID, etc.). From Econ 101, we know low supply leads to higher prices. And even though operating expenses have increased 16.3% for the average auto dealership in the U.S., pre-tax profits more than doubled in the first nine months of 2021.

This inelasticity of demand affords greater pricing power to dealers and manufacturers than they’ve previously achieved.

For years, retail has been obsessed with discounts. Think 10% for signing up for a mailing list, free shipping for orders over $25, or straight to the point: Black Friday/Cyber Monday. Automotive retailing is no exception, with incentives reaching above $4,500 per vehicle prior to the pandemic. As discussed last week, incentives have plummeted in the low inventory environment. Unlike knick-knacks bought in the Christmas season, many car buyers don’t have a reasonable substitute. When their car breaks down, they need a vehicle and can’t wait months for inventory levels to normalize. This inelasticity of demand affords greater pricing power to dealers and manufacturers than they’ve previously achieved.

Auto dealers and their manufacturers are much more profitable under the current operating environment while producing fewer vehicles, reducing execution risk. It’s easy to chalk up these good times to temporary dislocations caused by COVID that will eventually normalize. But in a capitalist society, economic downturns tend to bring back the phrase attributed to Winston Churchill around World War II, “never let a good crisis go to waste.” OEMs will look at how they’ve adapted since March 2020 and look to keep profits higher with more efficient operations.

Once the pandemic is finally in the rear view mirror, we think the level of inventories held on lots will be lower than pre-pandemic levels. While there is still a value to testing out the product before purchasing, we’ve seen other retail industries that hadn’t yet succumbed to ecommerce where certain buyers are now willing to buy sight unseen (see mattresses in a box). This shift in auto will reduce floor plan costs for dealers who can also downsize their real estate holdings or convert it to more service areas if they can find the technicians to fill the bays they already have. Smaller real estate requirements may enable dealerships to move to more cost-effective locations.

But the main concern from dealers we’ve talked to is this: what if prevailing supply conditions fundamentally change the franchised dealer model?

History of Dealer Franchising

To understand the status quo of automotive retailing, we start at the beginning, when automotive manufacturer franchising of dealerships began in 1898. Back then, there were numerous methods of selling vehicles, including franchise locations, direct sales from factory-owned stores, traveling salesmen, wholesalers, retail department stores, and consignment arrangements. As automobiles proliferated, manufacturers preferred outsourcing sales to the franchise model, so they could focus on their core competency of manufacturing vehicles. They would rely on entrepreneurs to understand their local market in terms of which models were popular and where best to situate the dealership within the market. This also lowered investment for the manufacturers who could instead plow those resources back into product development.

The franchise agreements were perceived as shifting risk downward to dealers and rewarding upwards to the manufacturers.

Once this investment was made by numerous “mom and pop” shops throughout the country, dealers lobbied to protect their investment. It was deemed unfair for the Big Three (Ford, GM, Chrysler) to be able to sell directly to consumers in lieu of through its dealers. Manufacturers already operate from a position of power as the sole provider of new vehicles to its franchisees, a risk known in valuation as “supplier concentration.” OEMs can unilaterally determine production levels, and according to a 1956 Senate Committee report, franchise agreements of the 1950s typically did not require the manufacturer to supply the dealer with any inventory and allowed the manufacturer to terminate the franchise relationship at will without any showing of cause. Manufacturers could overproduce and force dealerships to accept the cars with the threat of no inventory in the future. This occurred with Ford during the Depression. Thus, the franchise agreements were perceived as shifting risk downward to dealers and rewarding upwards to the manufacturers.

For perspective, restaurants don’t have similar franchise protections. For example, McDonald’s has both corporate owned and operated locations as well as franchise locations (approximately 93% of locations are franchisees). In this industry, there is heavy competition and franchisors often test out new products in their own locations before rolling them out to franchisees. This is quality assurance and also gives franchisors the ability to point to the success of a product so franchisees don’t feel like they’re being forced into something that may not appeal to their customers.

While dealers made numerous lobbying efforts at the Federal level in the 1930s to 1950s, they made little headway. In fact, a 1939 Federal Trade Commission report found that manufacturers pitting dealers against each other actually led to an intense retail competition which ultimately benefitted consumers. To get the protections they sought, dealers turned to state legislatures, which is why franchise laws are largely handled at the state level. Today, all 50 states have laws that protect dealers, though the strength and terms of these laws varies by state. Common terms include the prohibition of forcing dealers to accept unwanted cars, protection against termination of franchise agreements, and restrictions on granting additional franchises in a dealer’s geographic market area. As many dealers today know, the OEMs still have significant bargaining power in these latter two areas.

Direct Selling

The current market dynamic has prevailed for generations through numerous business cycles. Today, dealers are concerned that manufacturers may use electric vehicles (“EV”) as a means to skirt dealer franchise laws. Tesla has been very successful, particularly if you look at their share price, with its direct-to-consumer electric vehicle sales. OEMs naturally would like a piece of this (or anywhere near their valuation multiple).

While Tesla has encountered legal troubles with its direct selling model, it’s important to note the difference between Tesla and other manufacturers. Tesla never pursued a franchise dealer model. Therefore, direct selling cannot disadvantage dealers of its vehicles since they don’t exist. Tesla offers a luxury product and has yet to reach a meaningful scale. Unlike OEMs of the early to mid-1900s, their product has not garnered mainstream demand, and they can therefore be competitive in their niche by keeping few parties in between the manufacturer and the consumer. While the below graphic is instructive, the OEM tends to play the role of plant, distributor, and wholesaler, meaning there’s really only one extra layer between manufacturer and consumer in this industry.

Dealers naturally contend that direct-to-consumer EV sales should not be allowed as it could be a slippery slope to allowing the sale of all vehicles directly. There is nothing inherently different about the manufacturing and selling process as it relates to the powertrain of the vehicle. Tesla’s exception is not electric; it’s the lack of an existing dealer network. However, one of the benefits of the current dealership model is that consumers can return to the dealership to service their vehicle. If EVs deliver on their promise to require less maintenance than internal combustion engine (“ICE”) vehicles, maybe the need for this dealer network will be diminished in some regard.

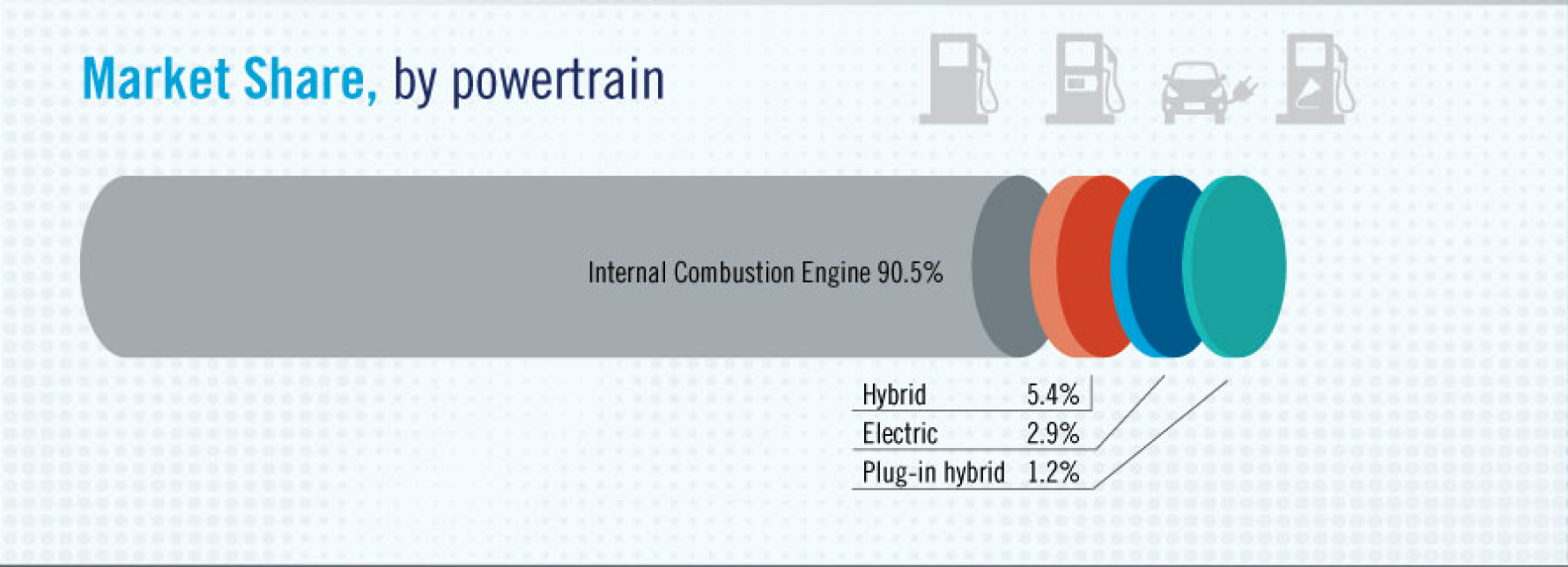

For now, electric vehicles are too expensive to be mainstream, but significant progress has been made on lithium batteries which have lowered costs. Still, massive investments in infrastructure will be necessary to make EVs practical. Electric vehicles are only 2.9% of the market, though combined with hybrids, alternative powertrains amount to 9.5%, with the remaining being internal combustion engines. While this is a relatively small piece of the market, it will likely grow over time.

Source: NADA Market Beat December 2021

Source: NADA Market Beat December 2021

Conclusion

Given the complexity of manufacturing automobiles and the heterogeneous preferences of consumers, we don’t think the recent shift to “just-in-time” delivery out of necessity will last. We believe electric vehicles will compose a much more meaningful market share, though we are less certain on the timing. While there are various proclamations of carbon-neutral by 2050 and the like, we think the market will determine when and how much electric vehicles hit the mainstream. If improved technology reduces costs and fears of range anxiety, EVs could be on the same playing field or even advantaged over ICE vehicles with higher upkeep costs (service and gas).

We don’t believe electric vehicles will meaningfully change dealer franchise laws. However, we believe the trends we’ve seen of smaller stores being gobbled up by increasingly larger auto groups will continue, which is partially due to the threat of direct selling. However, smaller dealers are also getting out with valuations peaking, tax policy uncertainty, and increasing capital requirements to invest in digital platforms, automated systems, and the infrastructure to support electric vehicles rather than the direct selling of these vehicles.

Mercer Capital provides business valuation and financial advisory services, and our auto team helps dealers, their partners, and family members understand the value of their business. Contact a member of the Mercer Capital auto dealer team today to learn more about the value of your dealership.

Auto Dealer Valuation Insights

Auto Dealer Valuation Insights