Year in Review: Across MedTech, Discipline Is a Recurring Theme

Last month, the medtech team at Mercer Capital attended the 2025 Musculoskeletal New Ventures Conference, where discussions among founders, venture investors, strategic acquirers, and advisors converged on a consistent message: activity in the industry is increasingly shaped by discipline around clinical differentiation, capital efficiency, and strategic coherence. Innovation continues across the ecosystem, though expectations around execution, funding, and exit visibility have tightened.

For early-stage companies, investors described an environment that supports new ventures, albeit with a greater emphasis on efficient capital deployment. Successful companies are pursuing leaner development strategies with earlier clinical or regulatory wins, rather than broad, capital-intensive pipelines. Incremental innovation, particularly in mature segments such as orthopedics, has been attractive when paired with platform scalability or data-enabled (AI) differentiation. Management quality and adaptability remain critical at this stage.

In contrast, as other observers have also noted, venture capital has favored select growth-stage and later-stage deals. Investments flowed into companies able to articulate coherent clinical and commercial strategies aligned with the priorities of large, strategic buyers. Clear narratives around end-market adoption, strategic fit, and integration potential have tended to lead to higher valuations across observed transactions.

Among large, established medtech companies, portfolio optimization was an ongoing effort. For public companies, exposure to higher-growth segments has increasingly supported better valuation multiples and relative equity performance. In response, strategic acquirers such as Stryker, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Johnson & Johnson have tuned their portfolios through targeted acquisitions, divestitures, and capital redeployment. For example, Stryker’s acquisition of Inari Medical reflects the appeal of the high-growth interventional markets with strong clinical differentiation, while its divestment of the spine business demonstrates an effort to exit slower-growth or less strategically differentiated segments. Similarly, Johnson & Johnson’s acquisitions of Shockwave Medical and V-Wave in 2024 augmented a cardiovascular platform focused on markets with long-term growth potential, while the announced separation of its DePuy Synthes orthopedics business signals a broader effort to simplify and sharpen strategic focus within its portfolio.

Overall healthcare IPO activity in 2025 was broadly in line with 2024 levels, with issuance concentrated among higher-quality medtech and life sciences companies rather than reflecting a broad-based market reopening. Offerings such as Caris Life Sciences, which combined scale, revenue growth, and a differentiated data-driven platform, were relatively well received, suggesting that the IPO window remains available but is selective.

Across various company stages and transactions, 2025 activity in medtech reflected a consistent emphasis on disciplined, capital-efficient growth. Whether among early-stage investments prioritizing focused development, later-stage companies articulating clear strategic fit, or large strategics actively reshaping portfolios, the common thread has been the pursuit of durable clinical differentiation and well-defined paths to scale or exit.

Documenting Fair Market Value: Lessons from Estate of Rowland v. Commissioner

A Guide for Estate Planners

Executive Summary

Business valuations that are well-documented with support for the methodology used and how the concluded value was arrived at are at the core of effective estate tax planning. The recent decision in Estate of Rowland v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo. 2025-76) reinforces that truth by showing how incomplete valuation documentation within Form 706 can jeopardize an otherwise straightforward portability election.

While Rowland involved a filing delay, the Court’s opinion makes clear that a deficient or poorly documented valuation can be just as damaging as a missed deadline. For estates holding closely held business interests, which are often significant and complex assets, the importance of thoroughly documenting the process of reaching fair market value cannot be overstated.

Background: The Portability Election and Form 706

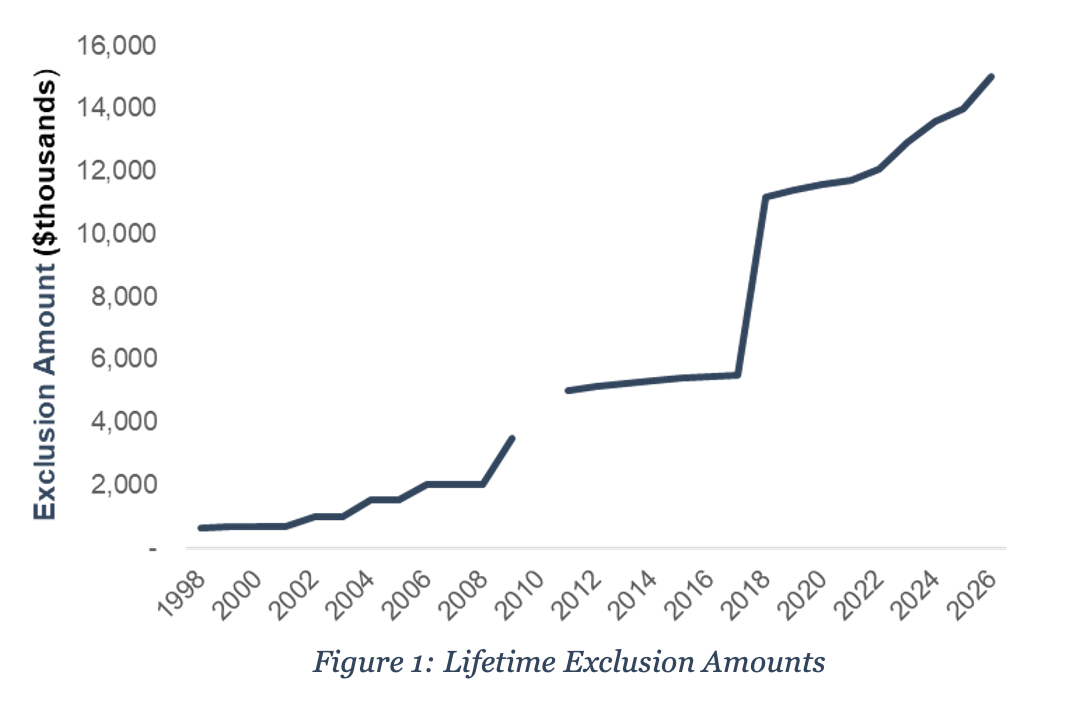

Under Internal Revenue Code § 2010(c)(5)(A), a surviving spouse may use any portion of the deceased spouse’s unused estate tax exclusion (the deceased spousal unused exclusion, or “DSUE”) if the first spouse’s executor properly elects portability.

That election must be made through a timely filed and complete Form 706. Even when an estate owes no estate tax, the return must contain detailed and supportable valuations of every asset, including business interests. Omitting or estimating values exposes the election to IRS challenge and potential invalidation.

Facts of the Case

Fay Rowland died in 2016, leaving an estate approximately $3.7 million below the filing threshold. Her executor obtained a six-month extension but filed Form 706 nearly six months after the extended deadline.

The return also lacked key valuation detail: 1) schedules reflected only estimated totals, not fair market values for individual assets; and 2) the executor claimed the “relaxed reporting” exception for assets passing to a surviving spouse, yet a portion of the estate passed to grandchildren’s trusts, making the exception inapplicable.

When the surviving spouse’s estate (Billy Rowland) later claimed Fay’s DSUE, the IRS denied the election, arguing the filing was neither timely nor properly prepared. The Tax Court agreed, which lead to Billy’s Estate paying approximately $1.5 million in additional taxes.

The Court’s Reasoning

Timeliness Was Not Enough

The Court held the return untimely, but even if it had met the filing window, it failed the requirement of being “complete and properly prepared.” Completeness, the Court emphasized, includes providing valuation information sufficient for the IRS to verify reported amounts and compute the DSUE accurately.

Valuation Documentation Is Integral to Completeness

Treas. Reg. § 20.2010-2(a)(7) requires a Form 706 filed solely to elect portability to include the same detail as a taxable return, except for assets passing entirely to a spouse or charity. The Rowland estate’s generalized estimates prevented the IRS from evaluating the DSUE computation.

The Court rejected arguments of substantial compliance and equitable relief, holding that valuation documentation is not simply a procedural technicality, but rather a statutory prerequisite.

Why Business Valuations Matter

For many families, closely held business interests comprise a large share of estate value. These assets require specialized valuation under Revenue Ruling 59-60. A well-supported valuation not only establishes compliance but also enhances the credibility of the entire filing.

A defensible business valuation requires:

- Identifying the rights and benefits of the interest being valued (control, transfer restrictions, etc.).

- Using relevant market evidence, including public comparables and transaction data.

- Applying sound financial analysis that addresses expected cash flows, risk, and growth prospects.

- Reporting clearly and effectively to the IRS and other readers.

Documentation: The Bridge Between Valuation and Compliance

The Rowland decision underscores that a valuation unsupported by documentation is no valuation at all. A properly prepared Form 706 should therefore include:

- Narrative descriptions of each business interest, outlining ownership, structure, and rights.

- Detailed valuation schedules explaining how conclusions were reached.

- Supporting exhibits, such as financial statements and methodology summaries.

- Explicit reference to appraisal standards that demonstrate compliance with USPAP and Treasury requirements.

Without these elements, a return fails the “complete and properly prepared” standard which is exactly what happened in Rowland.

Practical Guidance for Estate Planners

- Engage Qualified Appraisers Early. Business interests should be appraised by professionals experienced in federal transfer tax matters and IRS examinations.

- Coordinate Across Disciplines. Attorneys, accountants, and appraisers should align on ownership structures and entity specifics to ensure consistent reporting.

- Avoid Estimates or Prior-Year Values. Fair market value is determined as of the date of death; using approximations risks inconsistency with IRS standards.

- Explain Discounts and Assumptions. Clearly document the rationale for any discount for lack of control or marketability.

- Maintain Comprehensive Records. Preserve valuation reports, source data, and correspondence to support the filing if later reviewed or audited.

Conclusion

The Estate of Rowland v. Commissioner decision delivers a clear message: Form 706 filings must contain credible, well-documented fair market value determinations for all assets, particularly business interests, or risk invalidation. Portability hinges not only on timeliness but on the completeness and substantiation of reported values. The strength of the filing lies in the quality of its appraisals and the documentation supporting them.

At Mercer Capital, we integrate these principles into every estate and gift tax engagement, ensuring our valuation opinions are technically sound, clearly presented, and defensible which positions clients for successful outcomes under IRS scrutiny.

Valuations are a critical element of successful tax planning strategies and objective third-party valuation opinions are vital. Since 1982, Mercer Capital has provided objective valuations for estate, gift, and income tax matters across virtually every industry sector. To discuss your valuation needs in confidence, please contact one of our professionals or visit www.mercercapital.com.

Revisiting Solvency and Mark-to-Models

The fall of 2025 witnessed several high-profile bankruptcies that surprised the market, notable for both their suddenness and, in some cases, allegations of fraud. Pressure on consumer discretionary income —particularly among lower-income households—has been another theme. Of the top ten filings since September, seven were consumer-related, including Blink Fitness and Forever 21.

The November 4 Chapter 7 liquidation of Renovo Home Partners, with estimated liabilities of $100–$500 million, drew particular attention because it sat at the intersection of leveraged finance, private credit, and valuation. Renovo’s liabilities included a $150 million private credit loan from BlackRock TCP Capital Corp., a publicly traded BDC, marked at 100 as of September 30—just five weeks before the liquidation.

Backed by Audax Private Equity, Renovo was formed in January 2022 through the merger of three home improvement companies. While presumably solvent at inception, subsequent acquisitions and rising interest rates in 2022–2023 weighed on demand for home improvements as the company’s interest burden rose. Execution by management may have been an issue too. TCPC extended its $150 million loan (SOFR + 650 bps) in April 2024, which was carried at par at each subsequent quarter-end even though the company’s performance was deteriorating such that lenders converted some debt to equity in the spring of 2025 and the company elected to PIK in lieu of cash interest payments.

Solvency and Valuation

It is unclear whether Renovo obtained a solvency opinion when TCP extended the loan or when the platform was created. Regardless, the November 2025 bankruptcy filing raises questions about solvency and valuation at the time of the 2024 financing.

If (or had) the company obtained a solvency opinion, the following four questions would have been addressed:

- Does the fair value of the company’s assets exceed its liabilities after giving effect to the proposed action?

- Will the company be able to pay its debts (or refinance them) as they mature?

- Will the company be left with inadequate capital?

- Does the fair value of the company’s assets exceed its liabilities and surplus to fund the transaction?

Test 1: Balance Sheet Test

Does the fair value and present fair saleable value of assets exceed total liabilities, including contingencies?

This balance sheet test is a poorly named term for valuation whereby the subject company’s debt-free value is estimated using DCF, Guideline Public Company, Guideline M&A and Transactions (i.e., prior transactions or LOIs for the subject) methods. Sometimes, the NAV method will be utilized, too, for entities that are more akin to holding companies when assets can be marked to market.

Test 2: Cash Flow Test

Will the company be able to pay its liabilities as they mature?

This assesses whether projected cash flow can support debt service, considering:

- Revolver capacity: Sufficient liquidity to manage annual needs.

- Covenant compliance: Whether forecasts imply violations.

- Refinancing ability: Likelihood of refinancing maturing obligations.

Modeling can be complex or high-level, but assumptions about revenue growth and operating margins are often the key determinants for the cash flow test, which is based on common sense rules. If margins collapse, debt service is in trouble, and if it is steady or improves, then there presumably will not be issues.

Test 3: Capital Adequacy Test

Does the company have unreasonably small capital to operate?

Even if debt service is projected to be adequate, thin margins may leave little room for shocks. Adequacy is judged by pro forma leverage metrics (Debt/EBITDA, EBITDA/Interest) versus market and rating agency benchmarks.

Test 4: Capital Surplus Test

Do assets exceed the sum of liabilities and statutory capital?

This test mirrors the balance sheet approach but includes capital as defined under Section 154 of Delaware corporate law—namely, par value or total consideration received for stock issuance by Delaware-chartered companies.

Mark-to-Model

A forthcoming post will address how private credit is marked. The Renovo case stands out because TCPC marked its loan at par for five quarters, only to prospectively write it down to zero by year-end 2025. The situation has fueled existing widespread skepticism toward private market valuation practices—sometimes dubbed mark-to-myth. Ultimately, every asset marked-to-model becomes marked-to-market once it trades or, in the case of credit, is (or is not) repaid in full.

About Mercer Capital

Mercer Capital is a valuation and transaction advisory firm that values private equity and credit investments and provides solvency opinions for corporate boards, lenders, and other stakeholders involved in highly leveraged transactions.

The New Frontier Of Consumer Credit: Banks vs. Fintechs

Over the past three decades, community and regional banks have scaled back consumer lending while large banks and specialty finance companies have captured significant market share through economies of scale and robust origination platforms. Firms like American Express (NYSE:AXP), Capital One (NYSE:COF), Synchrony Financial (NYSE:SYF), and Ally Financial (NYSE:ALLY) leverage FDIC-insured deposit funding to power their lending operations. Most of these players, along with acquired entities like Discover Financial, operate at the intersection of payments and credit. Visa (NYSE:V) and Mastercard (NYSE:MC) are important payment partners to traditional banks, however.

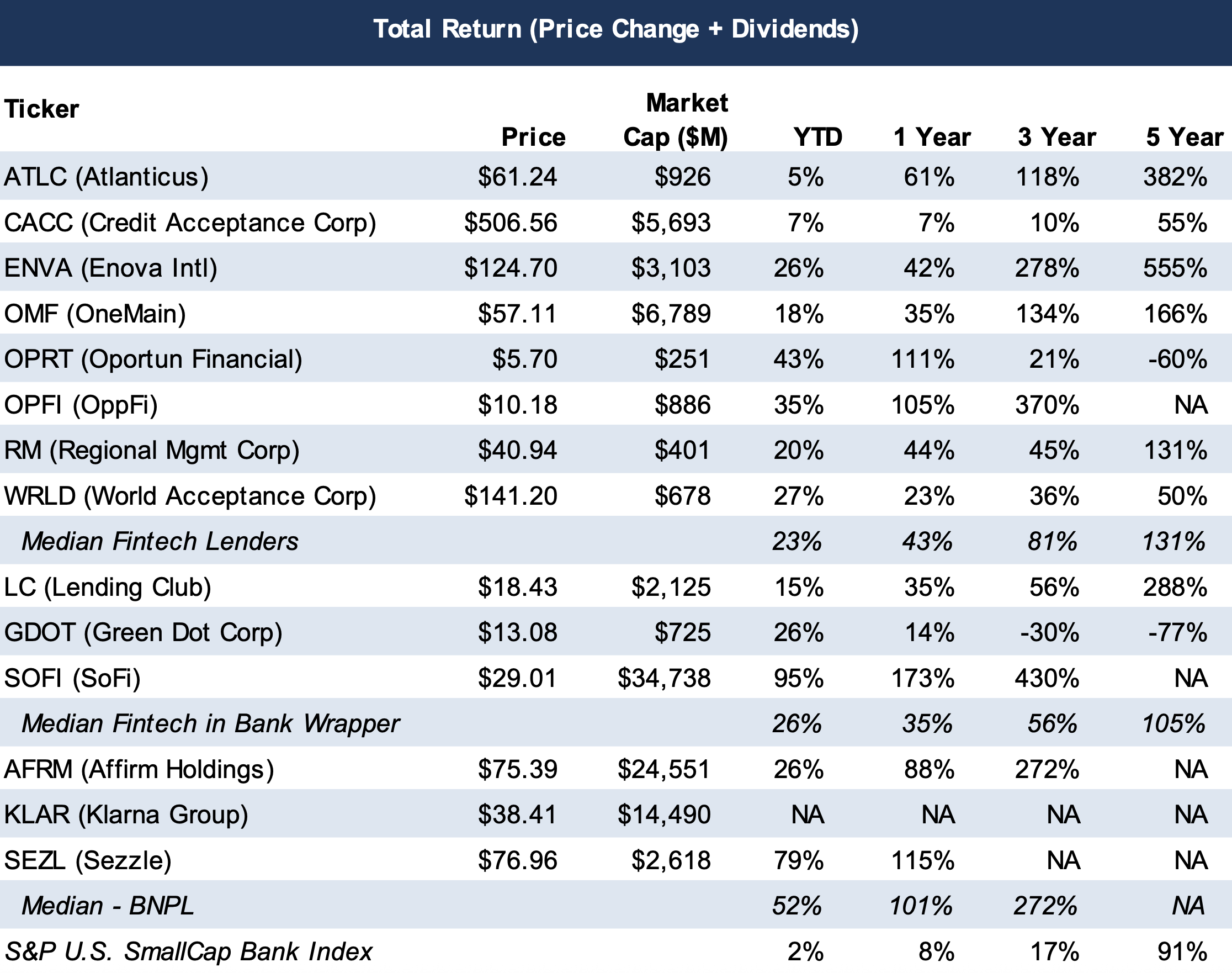

Since the GFC ended in 2009, fintech has transformed consumer credit and payments, intensifying competition for banks and expanding credit access, particularly for subprime and near-prime borrowers. Fintech lenders such as OppFi (NYSE:OPFI), Enova (NYSE:ENVA), and Oportun (NASDAQGS:OPRT) have carved out niches by using data-driven underwriting and digital delivery to serve underserved markets.

BNPL providers like Affirm Holdings (NASDAQGS:AFRM), Klarna (NYSE:KLAR), and Sezzle (NASDAQCM:SEZL) have further reshaped the landscape, offering easy payment options to consumers while boosting merchant sales. Established players like PayPal (NASDAQGS:PYPL) and Block (NYSE:SQ) have also embraced BNPL, with Block’s Afterpay and Cash App exemplifying a broader mission to democratize financial services.

The operating environment for these companies has been favorable this year because funding is relatively easy with wide open capital markets; the Trump Administration has virtually dismantled the CFPB and borrowing costs are declining with Fed rate cuts. In 2023, funding was difficult in the wake of SVB’s failure (e.g., Affirm struggled to complete one or more securitizations), and the CFPB under the Biden Administration presented a challenging regulatory environment.

The Rise of Alternative Lenders

Post-Dodd-Frank, many banks retreated from small-dollar and unsecured lending due to heightened compliance costs and regulatory scrutiny, which diminished the appeal of these products. Fintechs filled the gap, leveraging technology to serve subprime and near-prime consumers. Companies like OppFi paired underserved borrowers with credit products through digital channels, often via partnerships with small banks.

Using alternative data, machine-learning underwriting, and payroll-linked repayment models, these firms positioned themselves as modern alternatives to payday loans and credit cards. BNPL providers like Affirm and Klarna followed suit, offering short-term, interest-free or low-interest installment plans that gained traction amid post-COVID e-commerce growth.

Convergence of Banks and Fintechs

In recent years, the distinction between banks, fintech lenders and payments has blurred somewhat. Block’s company description captures this from a portfolio perspective:

Block builds technology to increase access to the global economy. Each of our brands unlocks different aspects of the economy. Square makes commerce and financial services accessible to sellers. Cash App is the easy way to spend, send, and store money. Afterpay is transforming the way customers manage their spending. TIDAL is a music platform that empowers artists. Bitkey is a simple self-custody wallet built for bitcoin. Proto is a suite of bitcoin mining products and services. Together, we’re helping build a financial system that is open to everyone.

For fintech lenders offering “lending as a service,” access to low-cost, stable deposit funding and perhaps greater regulatory certainty remains a coveted advantage of traditional commercial banking. Some have accessed bank funding. LendingClub acquired Radius Bank in 2021 to become a bank, and SoFi’s 2022 charter has bolstered its funding advantage. Others, like OppFi, rely on FDIC-insured bank partners to originate loans while retaining servicing or purchasing receivables.

Banks’ deposit-funded models offer a structural edge, especially after recent rate-driven deposit repricing while most fintechs and BNPL providers remain heavily dependent on capital markets and alternative lenders. Regulatory scrutiny, particularly of “rent-a-bank” partnerships, adds further complexity.

Valuation Dynamics

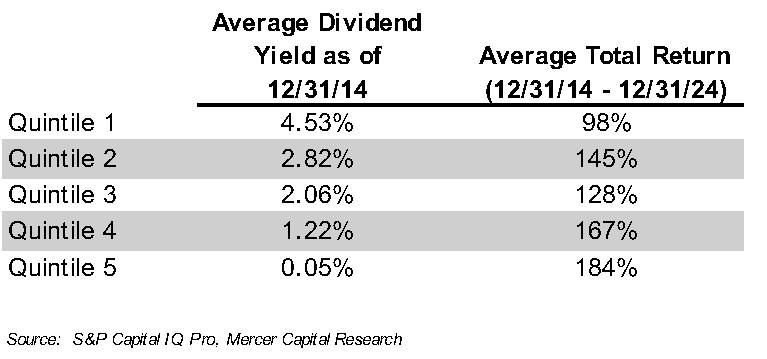

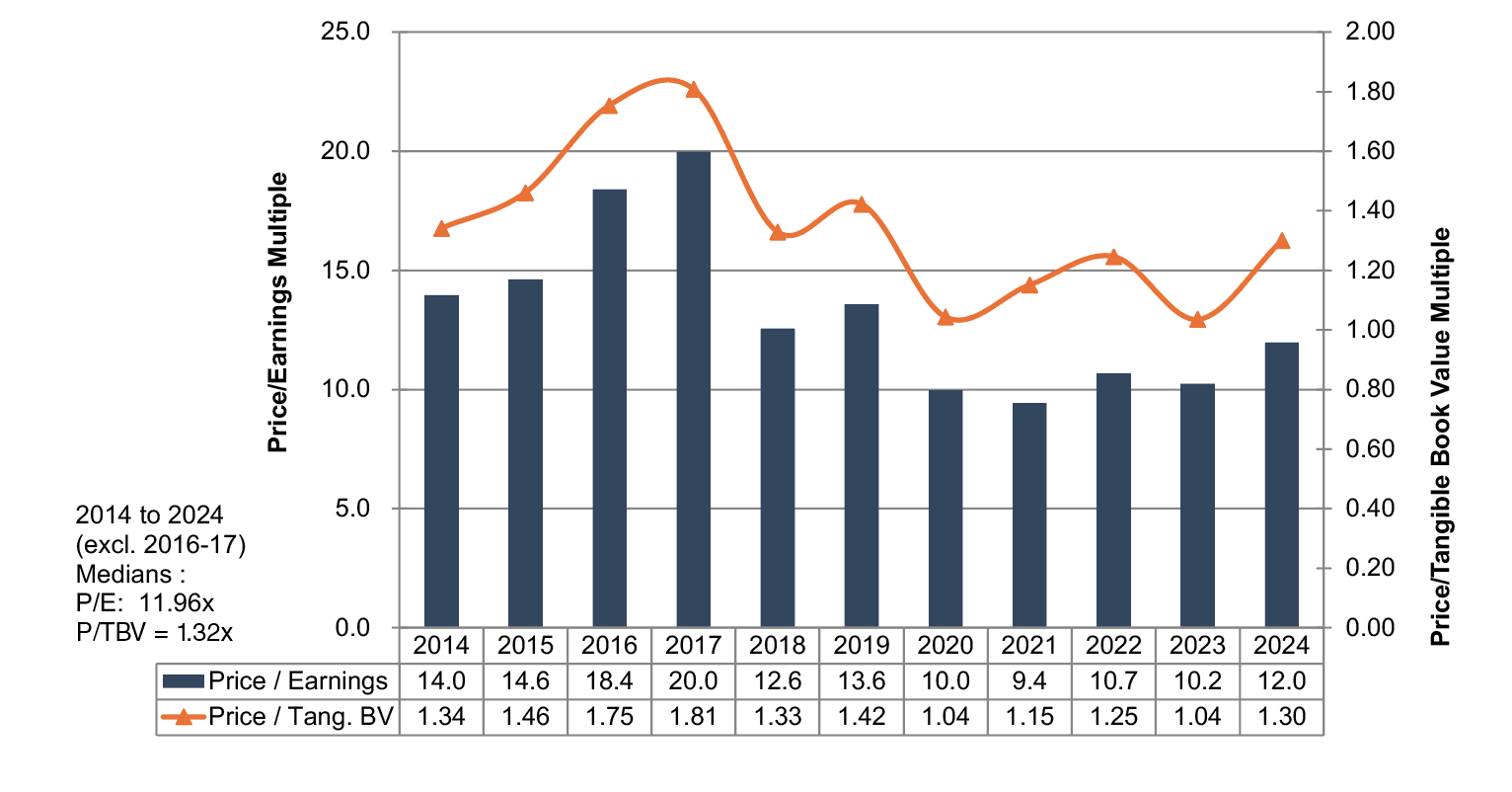

We are struck by the similarities and dissimilarities between banks and fintech lenders. Multiples are heavily influenced based upon investor perceptions of earnings growth (or free cash flow/excess capital) and risk (funding, compliance and credit). Overlaid are questions about the role of BNPL in providing incremental credit to subprime consumers and thereby sustaining consumer spending as student loan deferral end.

Valuations reflect these dynamics to some extent whereby lower growth implies lower earnings multiples for banks vs. fintech/BNPL whereas less funding and arguably regulatory risk translates to higher relative multiples. Perhaps the two big multiple determinants roughly offset between banks and the new economy lenders.

As of late October 2025, fintech lenders trade at ~7x forward earnings, often above book value, signaling market confidence in their scalability but wariness of credit and funding risks. Traditional banks, by contrast, command 9–10x earnings and 1.1–1.3x tangible book value, reflecting the stability of deposit funding and diversified income streams. High-performing fintechs and BNPL platforms with disciplined underwriting and scalable technology post strong returns on equity, commanding premium multiples. Weaker players, however, face low single-digit P/E ratios or trade below book value due to credit losses or regulatory missteps.

This “trust discount” applied to fintechs and BNPL providers creates opportunities. Banks can acquire fintech platforms to modernize underwriting and distribution, while fintechs with strong analytics but limited capital can benefit from deeper bank partnerships. For example, BNPL providers like Affirm could enhance bank offerings by integrating flexible payment options into existing credit products.

Conclusion

As digital lending evolves, success will hinge on balancing innovation with timeless banking principles based upon capital, credit and funding stability with innovation, growth and a larger addressable market that fintech/BNPL enables.

About Mercer Capital

Mercer Capital is a business valuation and financial advisory firm that values the securities and assets (e.g., portfolio fair value) of privately held financial and non-financial companies. Our advisory services entail M&A representation and the provision of transaction opinions (fairness and solvency). Please call if we can be of assistance.

Evaluating the Buyer’s Shares

Bank M&A has accelerated in 2025 with 144 announced transactions as of October 29 and looks to be set for ~175 deals this year compared to 133 last year. Other than the smallest deals, usually consideration paid to selling shareholders consists of the buyer’s common shares or a mix of shares and cash.

Accepting the buyer’s stock raises a number of questions, most of which fall into the genre of: what are the investment merits of the buyer’s shares? The answer may not be obvious even when the buyer’s shares are actively traded.

Our experience is that some, if not most, members of a board weighing an acquisition proposal do not have the background to thoroughly evaluate the buyer’s shares. Even when financial advisors are involved, there still may not be a thorough vetting of the buyer’s shares because there is too much focus on “price” instead of, or in addition to, “value.”

Key questions to ask about the buyer’s shares include:

- Liquidity of the Shares. What is the capacity to sell the shares issued in the merger? SEC registration and NASDAQ and NYSE listings do not guarantee that large blocks can be liquidated efficiently.

- Institutional Ownership and Index Membership. Is there much institutional ownership and what is the weighting of the buyer’s shares in various indices? Liquidity tends to improve with greater institutional ownership and index weighting.

- Profitability and Compounding. The banking model is predicated upon leveraging capital to produce shareholder returns (i.e., ROE and ROTE). Is ROE/ROTE competitive vs. peers through time? How is it generated (e.g., efficiency or parent company leverage)? Can the acquirer be described as a “compounder” of capital?

- Capital Management. How is capital allocated among reinvestment, dividends, share repurchases and M&A?

- Reported vs. Core Earnings. What is the quality of earnings as discerned by a comparison of reported vs. core earnings over a multi-year period (e.g., the last five years and five quarters)?

- TBVPS Dilution. What is the projected dilution to tangible BVPS at closing and how long to recoup it from less certain EPS accretion once expense saves are realized?

- Seller Pro Forma Perspective. What is the pro forma impact to tangible BVPS, EPS and DPS from the perspective of selling shareholders?

- Analyst Estimates. If the buyer is publicly traded and has analyst coverage, how do the budget and management’s formal or informal projections for the next couple of years compare with the Street’s consensus?

- Valuation. How does the current valuation (P/E and P/TBV) compare to current peers and what has the valuation range been in absolute terms and compared to peers over the past decade?

- Share Performance. How have the shares performed compared to peers and relevant indices over multi-year holding periods and how have changes in valuation impacted the performance?

- Pro Forma Capital. Will the buyer have ample regulatory capital, and is the parent company capital structure overly-levered and/or complex?

The list does not encompass every question, but it illustrates that a liquid market for a buyer’s shares does not necessarily answer questions about value, growth potential and risk profile. We at Mercer Capital have extensive experience in valuing and evaluating the shares (and debt) of financial service companies garnered from over four decades of business.

The Discount for Lack of Marketability in Divorce: Real World Examples and Considerations – Part 2

In Part 1 of this post, we defined valuation discounts such as the discount for lack of control and discount for lack of marketability. We discussed the difference between fair value and fair market value, illustrated the importance of the prevailing state statute, and gave arguments for and against employing valuation discounts in a divorce context. Now we will discuss common drivers of marketability discounts and contextualize them with common provisions in partnership agreements and go through a case study.

Common Drivers of Marketability Discounts

Valuation discounts are not arbitrary devices to reduce value in litigation. They exist because of real-world features that make certain ownership interests more difficult to sell or less attractive to outside investors. In fact, many of these features are intentionally built into partnership agreements or shareholder arrangements to protect the business and its stakeholders. A few include:

- Restrictions on Transfer: Many closely held businesses restrict or require approval for ownership transfers. These provisions seek to keep control within a family, a select group of partners, or a trusted ownership base. While these restrictions enhance stability for the company, they limit an individual investor’s ability to sell readily, creating real economic limitations that justify a discount.

- Distribution Policy: Some companies retain earnings to fund growth, acquisitions, or working capital needs rather than distributing profits. This policy is often in the long-term interest of the business, but for minority owners it means cash returns are uncertain or deferred.

- Governance and Control Provisions: Voting thresholds, rights of first refusal, and mandatory buy-sell provisions can protect a company’s continuity but can also constrain minority investors. These contractual realities reduce the pool of willing buyers and reduce near-term optionality and liquidity for minority investors.

While there are many potential provisions in governance documents that would influence valuation discounts, the above are some of the most common. The degree to which these provisions impair the ability to achieve liquidity influences the magnitude of the discount. In most cases, experts agree that a DLOM applies, but they may disagree as to the magnitude.

A Real World Example

If a spouse invests liquid marital funds into a less liquid minority interest in a private company, that spouse could later argue that the subject interest lacks marketability. Thus, the value of this asset for division would be lower.

Suppose a divorcing party invested $1,000,000 from the marital estate for a 25% stake in a limited partnership which invests in real estate. Next, let’s assume the underling real estate was acquired for $10,000,000, financed by $6,000,000 in debt and $4,000,000 in equity, from four investment partners who each contributed $1,000,000.

On the date of contribution, it would be hard to argue that each individual’s investment is worth anything other than $1,000,000. But what if this investment had occurred many years prior to the divorce proceedings? What is the property worth now? What is the remaining debt balance? Has the partnership been making regular distributions?

For this fact pattern, let’s assume the parties have hired real estate appraisers to value the property for the divorce and it is worth $12,500,000, and the debt balance has been paid down to $4,500,000 for an equity value of $8,000,000, or $2,000,000 pro rata for each partner.

If the divorce is filed in a state fair market value state, discounts for lack of control and/or marketability would likely apply, reducing the value. If the 25% subject interest is determined to support a combined valuation discount of 30%, that would be applied to the $2,000,000, resulting in a nonmarketable minority value of $1,400,000. While there are legitimate reasons (and support) for this discount, the non-owner spouse would likely be considered disadvantaged if the investment occurred after divorce proceedings commenced. This is a clear example of why temporary restraining orders (TROs) are common in divorce. These types of orders seek to protect the other spouse from a DLOM that one could argue was intentionally manufactured.

The Bottom Line

The debate over DLOMs in divorce comes down to economic equality versus market reality. Should the valuation(s) and resulting divisions aim to replicate what the open market would pay? Or should there be more consideration such that the non-owner spouse isn’t disadvantaged by a “hypothetical” discount? For divorcing couples with a privately held minority business interest, the answer depends on the standard of value in the relevant jurisdiction. Furthermore, the facts and circumstances of the subject interest may support a discount on the lower or higher end of a reasonable range.

This is precisely why we typically caveat responses to such questions with “facts and circumstances matter.” The jurisdiction matters. The intent and timing of the investment matter. The relationship between the other investing parties matters. What if the other three partners in the hypothetical venture were all related to one of the divorcing spouses… and the partnership agreement states that owners may only be blood-line relatives (limiting a potential pool of buyers for hypothetical resale)? A trier of fact is likely to consider all these factors, even in a jurisdiction that does and doesn’t allow for discounts.

This makes it even more important that the retained business valuation expert is experienced with engagements requiring the determination of discounts for lack of marketability and control, what quantitative and qualitative methodologies to consider, documents, data & information to consider, among other factors. Contact a member of Mercer Capital’s litigation support services team today.

Third-Party Fairness Opinions in Continuation Funds: Lessons from Deep NAV Discounts

The Paramount Deal: A Reality Check on Valuations

On September 17, 2025, alternative asset manager Rith Capital Corp. (NYSE:RITM) agreed to acquire office REIT Paramount Group, Inc. (NYSE:PGRE) for $1.5 billion cash, or $6.60 per share. Paramount is an integrated REIT that manages and owns 13.1 million square feet of Class A offices (86% occupancy rate) in New York and San Francisco.

Word of the deal, but not the price, leaked because the shares rose 4% on September 16 to $7.39 per share on volume that was 5x above average. Relative to the pre-leak closing price on September 15, the deal price represented a 7% discount and equated to 48% of book value and 10.2x funds from operations (“FFO”).

By way of comparison, RITM’s shares as of year-end 2019 closed at $13.92 per share, which equated to 82% of book value and 14.5x LTM FFO. And for those who can time the market, the shares traded just below $4.00 per share immediately after “Liberation Day” and thereby provided a great five-month return.

When Book Value Isn’t Market Value

Paramount was not a high-flyer. The dividend was suspended in September 2024 after having been cut in June 2023 and December 2020. The stock traded below book value for years. The public market and change-of-control transactions imply the carrying value of the assets was too high though the 2024 10-K notes that real estate assets carried at cost less accumulated depreciation are individually reviewed for any impairment.

Aside from an impairment issue, GAAP did not dictate that the $8.3 billion land, buildings and improvements be marked-to-market so that book value could be directly equated with net asset value (“NAV”). Nonetheless, investors did so daily yet still over-estimated NAV that a competitive process revealed it to be in a change-of-control transaction.

Secondary Pricing as % of NAV (by weighted average volume)

The Broader Challenge: Overstated NAVs in Private Markets

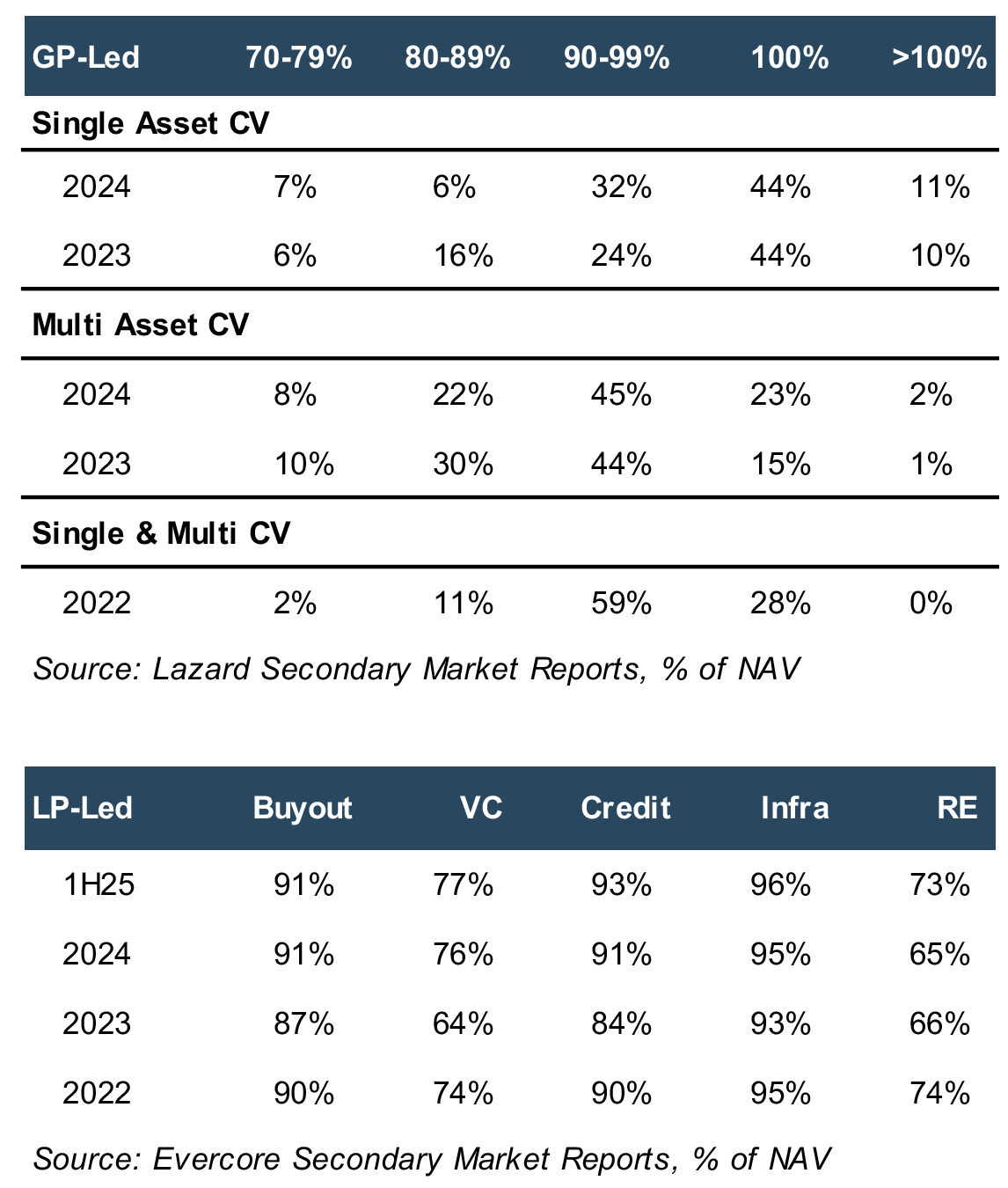

Paramount illustrates what some think is a pervasive issue in private equity and to a lesser extent private credit whereby fair value marks and therefore NAVs are too high. An unwillingness to recognize reality may be one reason PE exits are too low relative to investment. Assets are held in the hope that next year conditions will be better – the M&A market improves, the company’s earnings will be higher, etc.

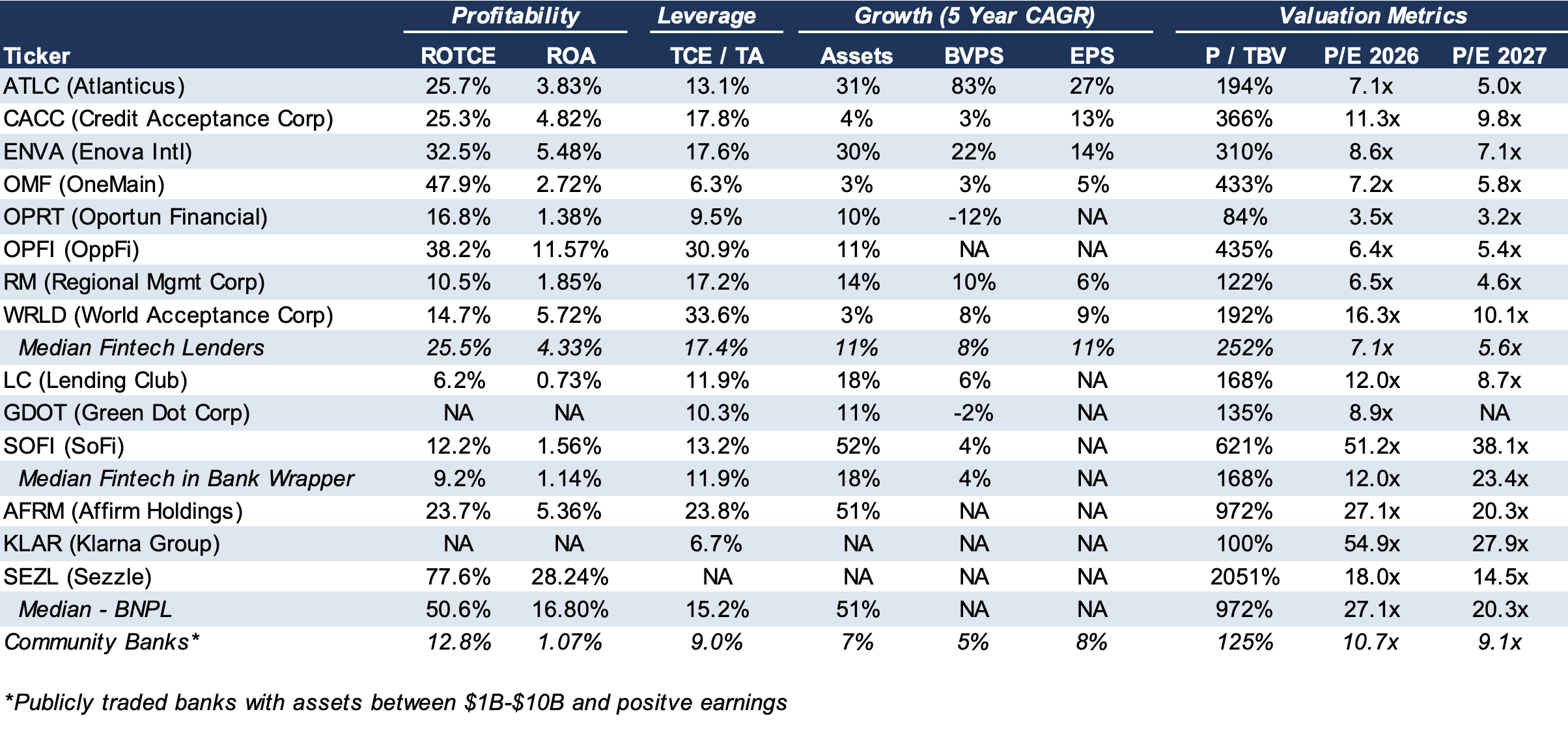

Continuation Funds and Valuation Gaps

Continuation vehicles (“CV”) with five year lives that acquire assets from PE funds are a bridge to a potentially better tomorrow, but valuation gaps today based upon what the CV asset marketing process reveals vis-?-vis the current mark can be material though the data is nuanced. Evercore in its mid-year 2025 update estimates that 87% of GP-led secondaries transacted at less than NAV. Lazard estimates that 90% of single-asset and 70% of multi-asset GP-led secondaries transacted at 90% of NAV or higher in 2024. However, the data does not distinguish between cash paid at closing and contingent earn-out payments; so, the effective transaction price vs NAV may be wider.

LP-led secondaries offer additional perspective—albeit for a portfolio interest vs one or more ~plum assets—with discounts to NAV on the order of 10% for buyout interests vs 25% for venture and real estate assets. One could argue the LP discount or some portion of it reflects an illiquidity discount vs appropriateness of the NAV mark for

the portfolio.

Governance Under Pressure: The Business Judgment Rule

Directors of corporations operate under the long-held concept of the Business Judgment Rule (“BJR”) where courts generally will not second guess decisions as long as directors do not violate the fiduciary triad of care (informed decision making), loyalty (interests aligned with shareholders, conflicts fully disclosed), and good faith. Application of the BJR to GPs varies by state and will be viewed through the lens of the partnership agreement when disputes arise.

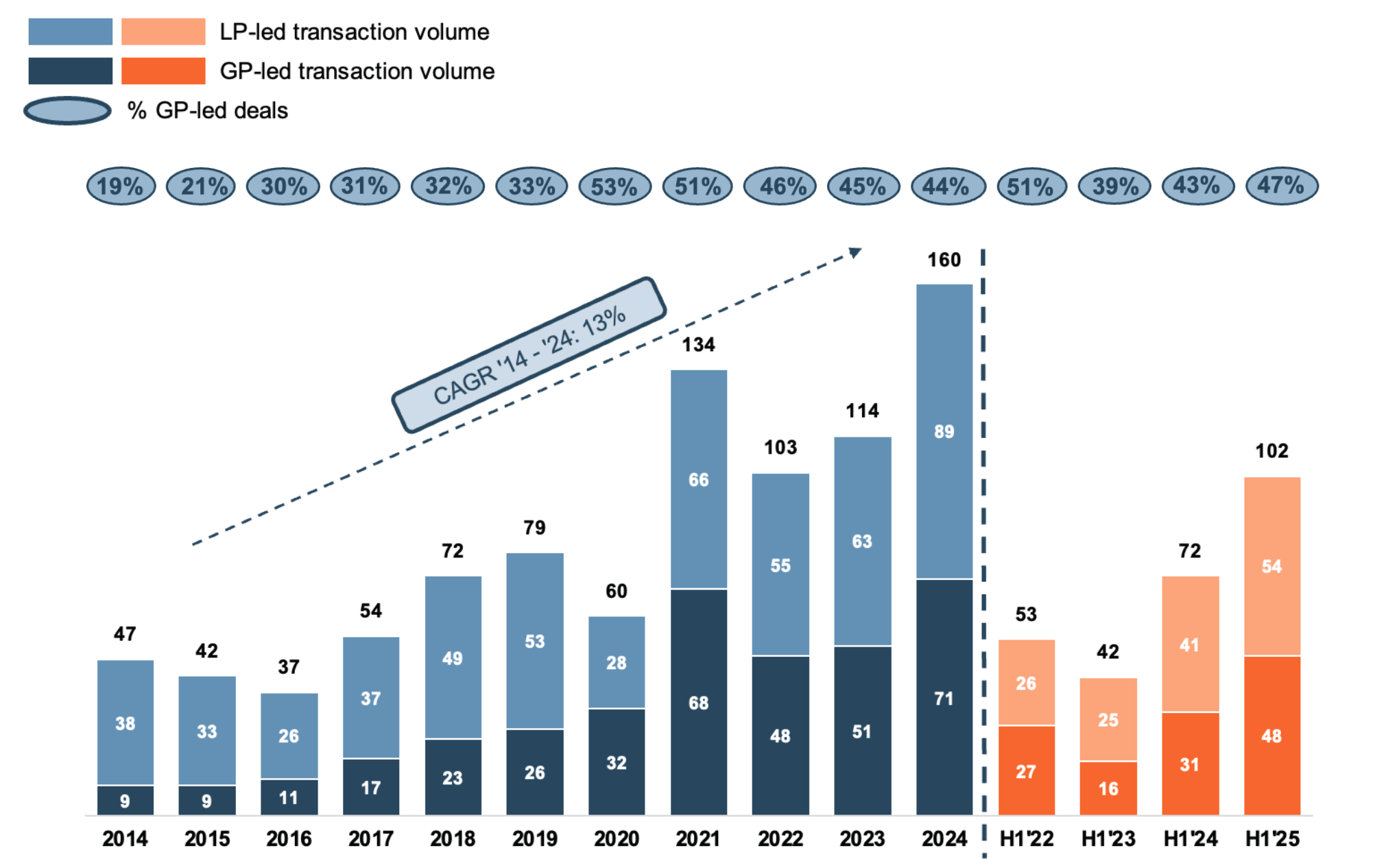

Secondary Market Transaction Volume Over Time ($bn)

BJR murkiness notwithstanding, GP-led secondary transactions are problematic from a governance perspective because GPs are both seller and buyer, and the GP has a financial incentive to extend the period on which management fees and carry are earned.

The Role of Fairness Opinions

The institutionalization of GP-led continuation funds has led to the development of a fair dealing process to address the loyalty question—at least outwardly—in which a third-party financial advisor markets the subject asset(s) to investors who would capitalize a CV. The proposal with the combination of the best price and terms with confirmed access to capital will be selected to transact subject to a conflict of interest waiver from the LP advisory committee (“LPAC”).

Third-party fairness opinions emerge as indispensable here for the LPAC, bridging process and price vis-?-vis the historical fair value marks. Unlike binary “fair/unfair” verdicts, these assessments—rooted in rigorous due diligence—evaluate the marketing process, transaction terms from a financial point of view, dissecting NAV assumptions, cap rates, and exit multiples against market comps.

Best Practices and Industry Guidance

For continuation funds, the stakes are higher: GPs must demonstrate that discounts reflect arm’s-length negotiations, not convenient happenstance. The CFA Institute research on ethics in private markets emphasizes competitive bidding processes to mitigate manager incentives—strong financial additions like promoted interests in the new fund can skew outcomes toward overvaluation. ILPA’s 2023 guidance amplifies this, urging 30-45 day timelines for LP re-underwriting, full disclosures on advisor conflicts, and LPAC pre-approvals to safeguard alignment.

Beyond a Checkbox: Upholding Fiduciary Integrity

Ultimately, fairness opinions are not mere check boxes; they are part of the governance protocol to address the care and loyalty duties that are the cornerstone of the BJR.

About Mercer Capital

Mercer Capital is an independent valuation and financial advisory firm founded in 1982, specializing in business valuation, corporate transactions, and financial opinions. With offices in Dallas, Houston, Memphis, Nashville, and Winter Park, we serve private equity sponsors, portfolio companies, and institutional investors in valuing complex, illiquid equity, credit, mezzanine and other such securities. Our fairness opinion practice, a cornerstone of our expertise, provides objective assessments for conflicted transactions such as GP-led secondaries and continuation funds. Drawing on deep market insights and rigorous due diligence, we help clients navigate governance challenges, ensure regulatory compliance, and maximize stakeholder alignment. For more, visit mercercapital.com.

2025 Core Deposit Intangibles Update

Since Mercer Capital’s most recently published article on core deposit trends in September 2024, deal activity in the banking industry is showing some signs of improvement. There were 77 deals announced in the first and second quarters of 2025 as compared to 65 during the same period of 2024. It is possible that transactions will pick up further due to a less stringent regulatory environment in the Trump administration. Additionally, funding pressure has eased significantly over the last two years, and mark-to-market adjustments on loans and deposits are declining. Despite short-term interest rates declining from their peak, we have seen a marginal uptick in core deposit intangible values in the most recent deal announcements.

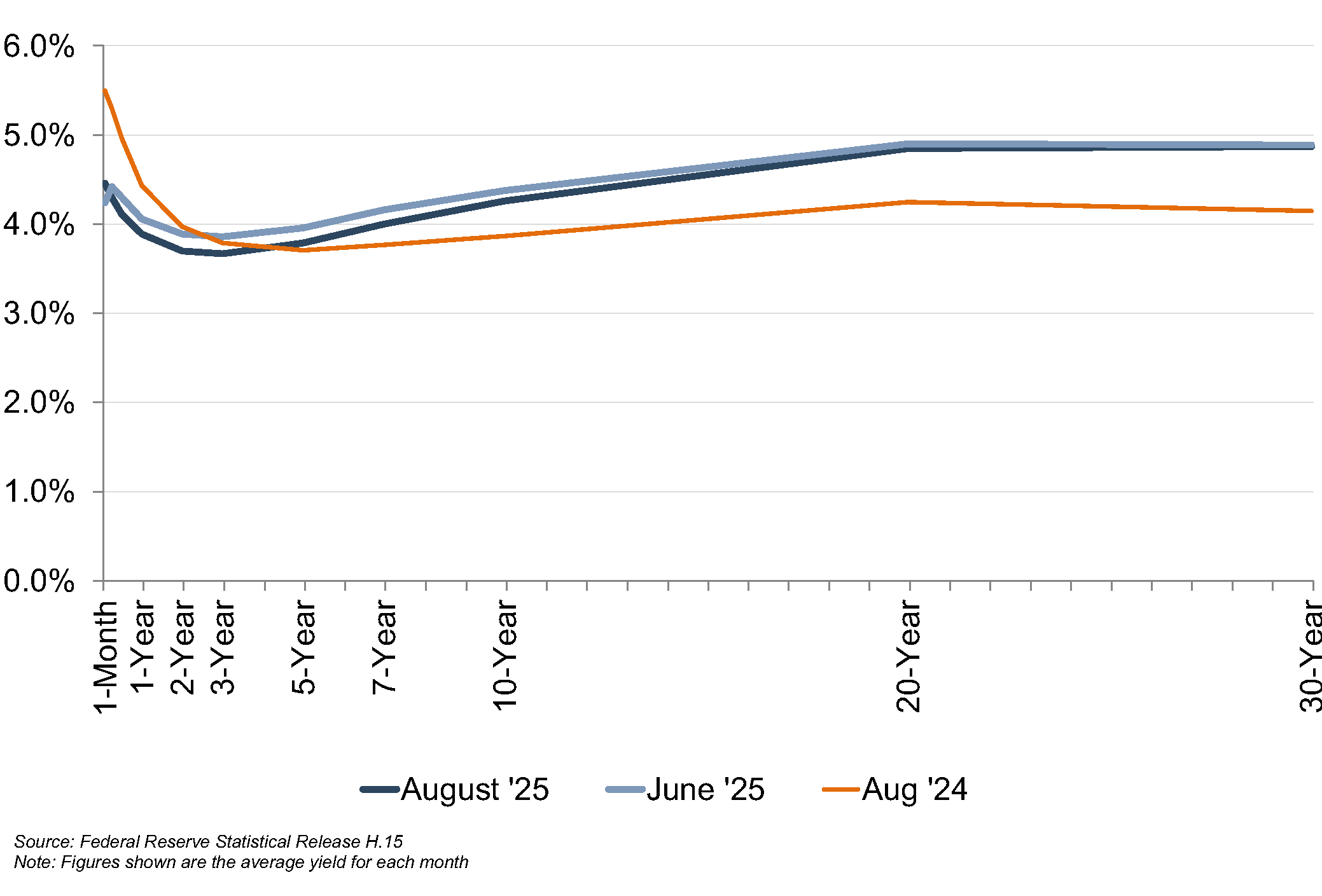

Figure 1 :: U.S. Treasury Yield Curve

While many factors are pertinent to analyzing a deposit base, a significant driver of value is market interest rates. All else equal, lower market rates lead to lower core deposit values. In its September 2024 meeting, the Federal Reserve reduced the target federal funds rate by 50 basis points. This was the first downward adjustment since the FOMC began increasing rates in March 2022. In its third and fourth quarter 2024 meetings, the Federal Reserve reduced the target federal funds rate by 25 basis points at each meeting. After several quarters of steady rates, an additional 25 basis point reduction occurred in the September 2025 meeting. These cuts left the benchmark federal funds rate in a range between 4.00% and 4.25%.

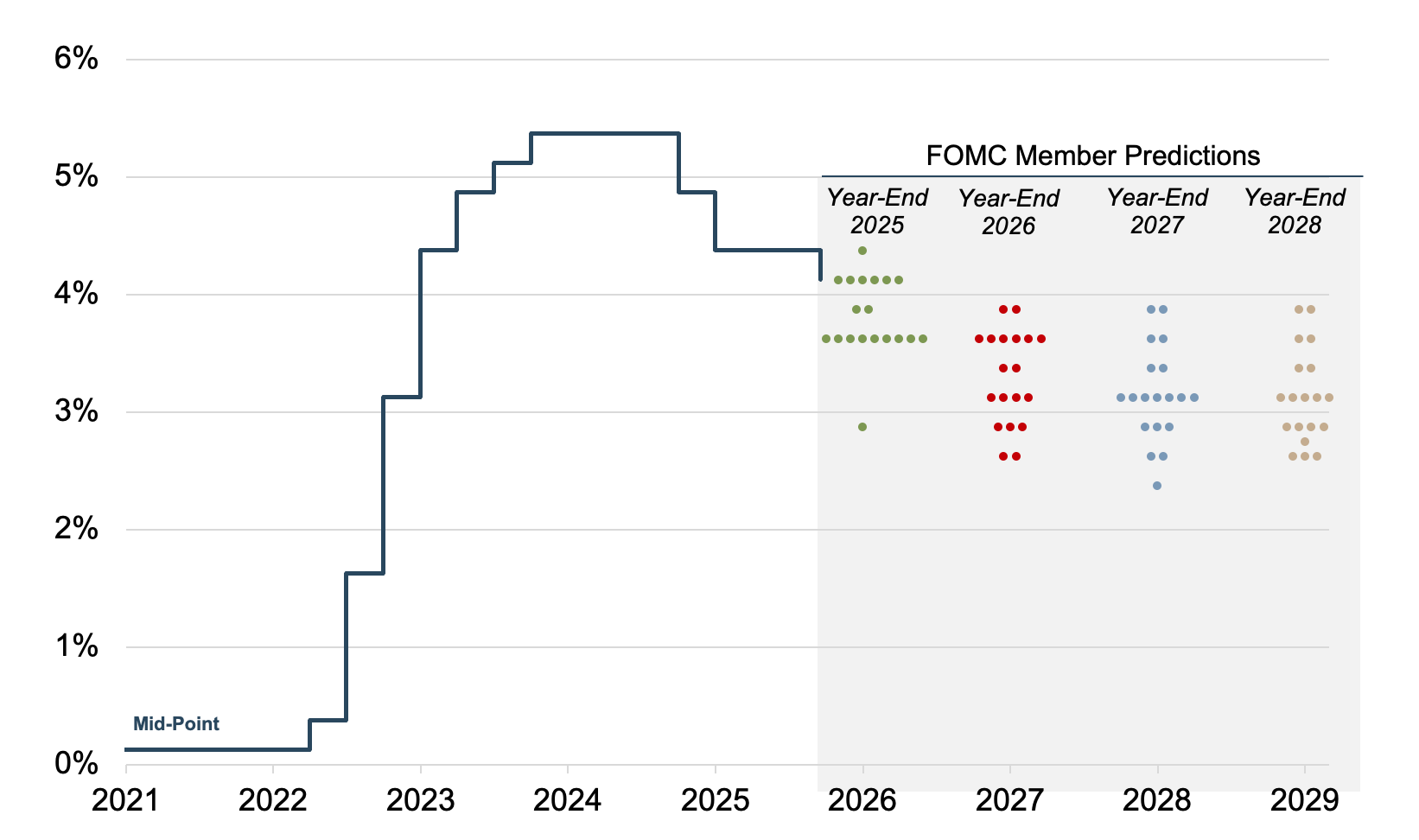

Figure 2 :: Federal Reserve Dot Plot

Source: Federal Reserve Summary of Economic Projections

Source: Federal Reserve Summary of Economic Projections

Note: Figures shown represent predictions for the end of the calendar year

As shown in Figure 1, on the previous page, the yield curve for U.S. Treasuries has shifted downward relative to last year at this time for terms of less than five years, and the market expects further downward movement in short-term rates in the near-term.

The Federal Reserve’s “dot plot”, presented in Figure 2, on the previous page, exhibits a wide dispersion of expectations for the near term, especially for 2026. Although the magnitude of future adjustments to the target rate is unclear, the expectation is clearly for lower rates.

Trends In CDI Values

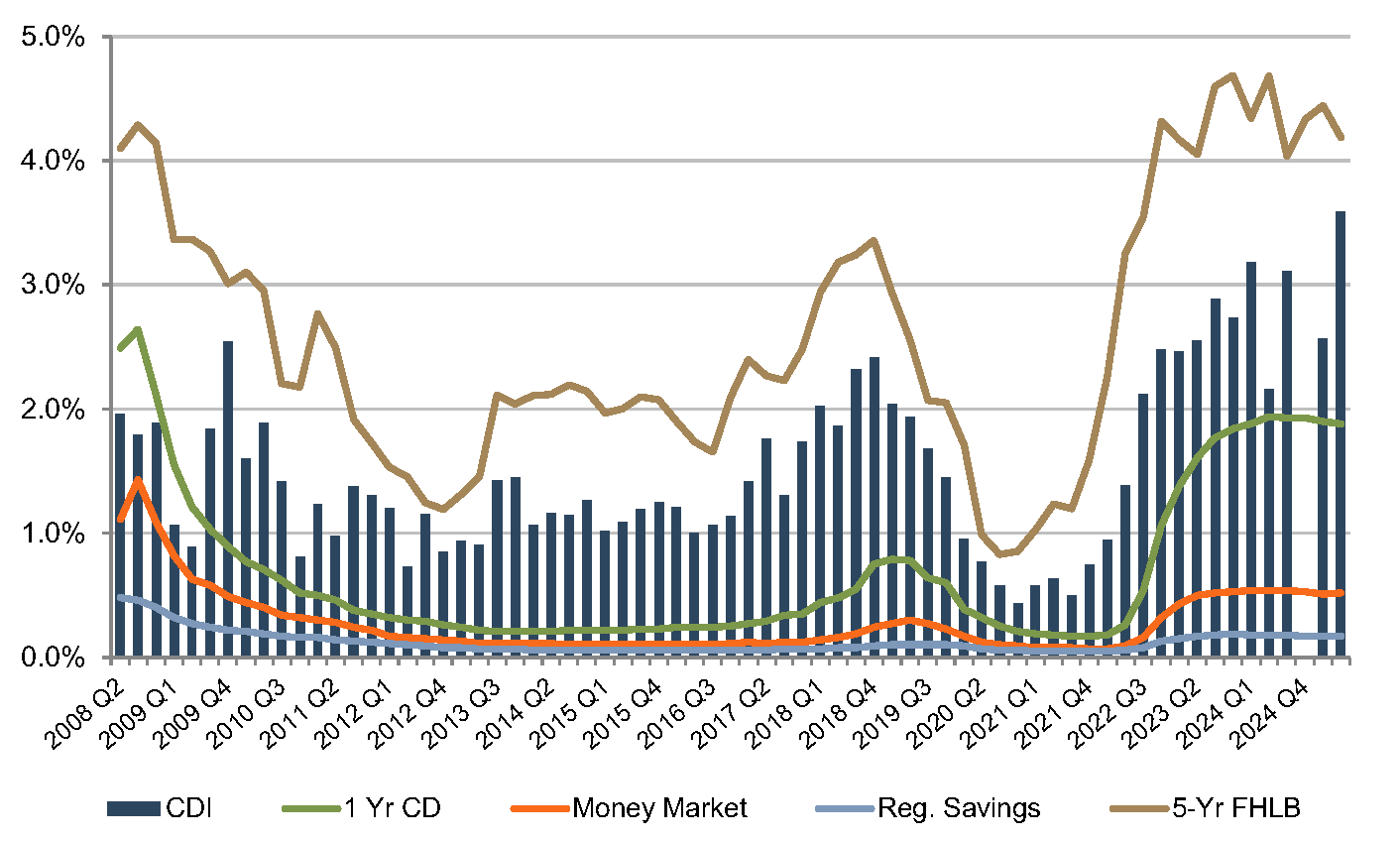

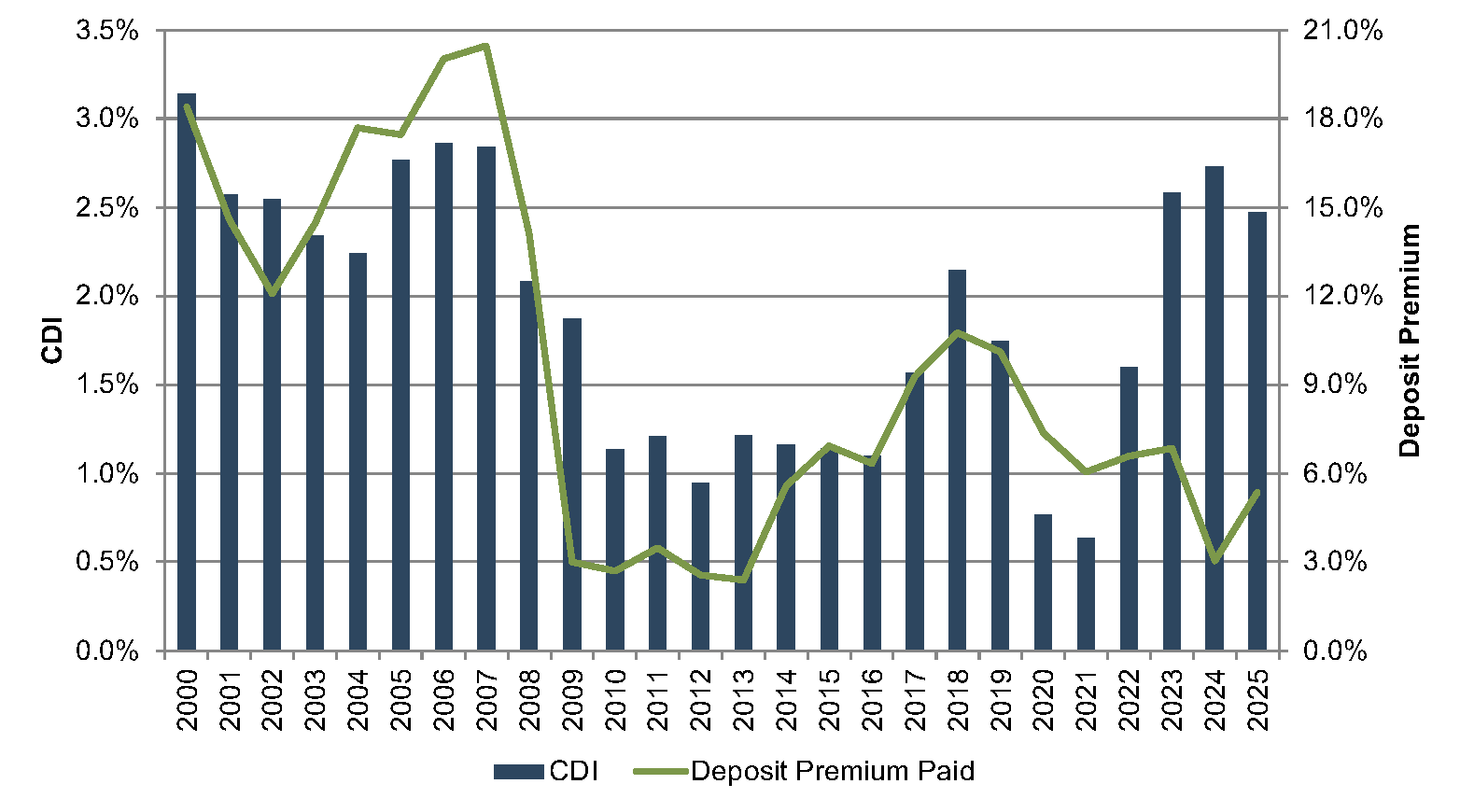

Using data compiled by S&P Global Market Intelligence, we analyzed trends in core deposit intangible (CDI) assets recorded in whole bank acquisitions completed from 2000 through mid-September 2025. CDI values represent the value of the depository customer relationships obtained in a bank acquisition. CDI values are driven by many factors, including the “stickiness” of a customer base, the types of deposit accounts assumed, the level of noninterest income generated, and the cost of the acquired deposit base compared to alternative sources of funding. For our analysis of industry trends in CDI values, we relied on S&P Global Market Intelligence definition of core deposits. In analyzing core deposit intangible assets for individual acquisitions, however, a more detailed analysis of the deposit base would consider the relative stability of various account types. In general, CDI assets derive most of their value from lower-cost demand deposit accounts, while often significantly less (if not zero) value is ascribed to more rate-sensitive time deposits and public funds. Non-retail funding sources such as listing service or brokered deposits are excluded from core deposits when determining the value of a CDI.

Figure 3 summarizes the trend in CDI values since the start of the 2008 recession, compared with rates on 5-year FHLB advances. Over the post-recession period, CDI values have largely followed the general trend in interest rates—as alternative funding became more costly in 2017 and 2018, CDI values generally ticked up as well, relative to post-recession average levels. Throughout 2019, CDI values exhibited a declining trend in light of yield curve inversion and Fed cuts to the target federal funds rate during the back half of 2019. This trend accelerated in March 2020 when rates were effectively cut to zero.

Figure 3 :: CDI as % of Acquired Core Deposits

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

CDI values have been somewhat flat compared to last year, averaging 2.47% through mid-September 2025. Excluding one transaction with an unusually low core deposit intangible ratio, the average is closer to 2.70%. This compares to a 2.73% average for all of 2024, 2.58% for 2023, 1.60% for 2022 and 0.63% for 2021. Recent values are above the post-recession average of 1.53%, and on par with longer-term historical levels which averaged closer to 2.5% to 3.0% in the early 2000s.

As shown in Figure 3, reported CDI values have followed the general trend of the increase in FHLB rates. However, the averages should be taken with a grain of salt. The chart is provided to illustrate the general directional trend in value as opposed to being predictive of specific indications of CDI value due the following factors:

- The September 17th Federal Reserve rate cut is not reflected in the data above. While the impact on CDI values of one 25 basis point reduction in the Fed Funds target rate may not be highly material—given that the forward rate curve has anticipated falling short-term interest rates for some time—continued reductions in the Fed Funds target rate or downward shifts in the yield curve may result in a larger decline in CDI values.

- General market averages do not reflect the individual characteristics of a particular subject’s deposit base.

- Most of the values presented above reflect the estimated core deposit intangible value at deal announcement, rather than the final core deposit intangible value as determined post-closing. Additionally, the quantity of transactions with known core deposit intangible value is fairly low for many periods. In the fourth quarter of 2024, for example, no transactions occurred with a disclosed core deposit intangible value.

Forty-four deals were announced in July, August, and the first half of September, and 13 of those deals provided either investor presentations or earnings calls containing CDI estimates. Excluding two outliers with an average estimated CDI value of 1.3%, these CDI estimates ranged from 2.0% to 3.9% with an average of 3.0%. However, the CDI premiums cited in investor presentations can be somewhat difficult to compare, as acquirers may use different definitions of core deposits when calculating the CDI premiums reported to investors. For example, some acquirers may include CDs in the calculation, while other buyers may exclude CDs or include only certain types of CDs.

Generally, we expect CDI values to fall in concert with falling market interest rates. How fast they decline could depend on several factors:

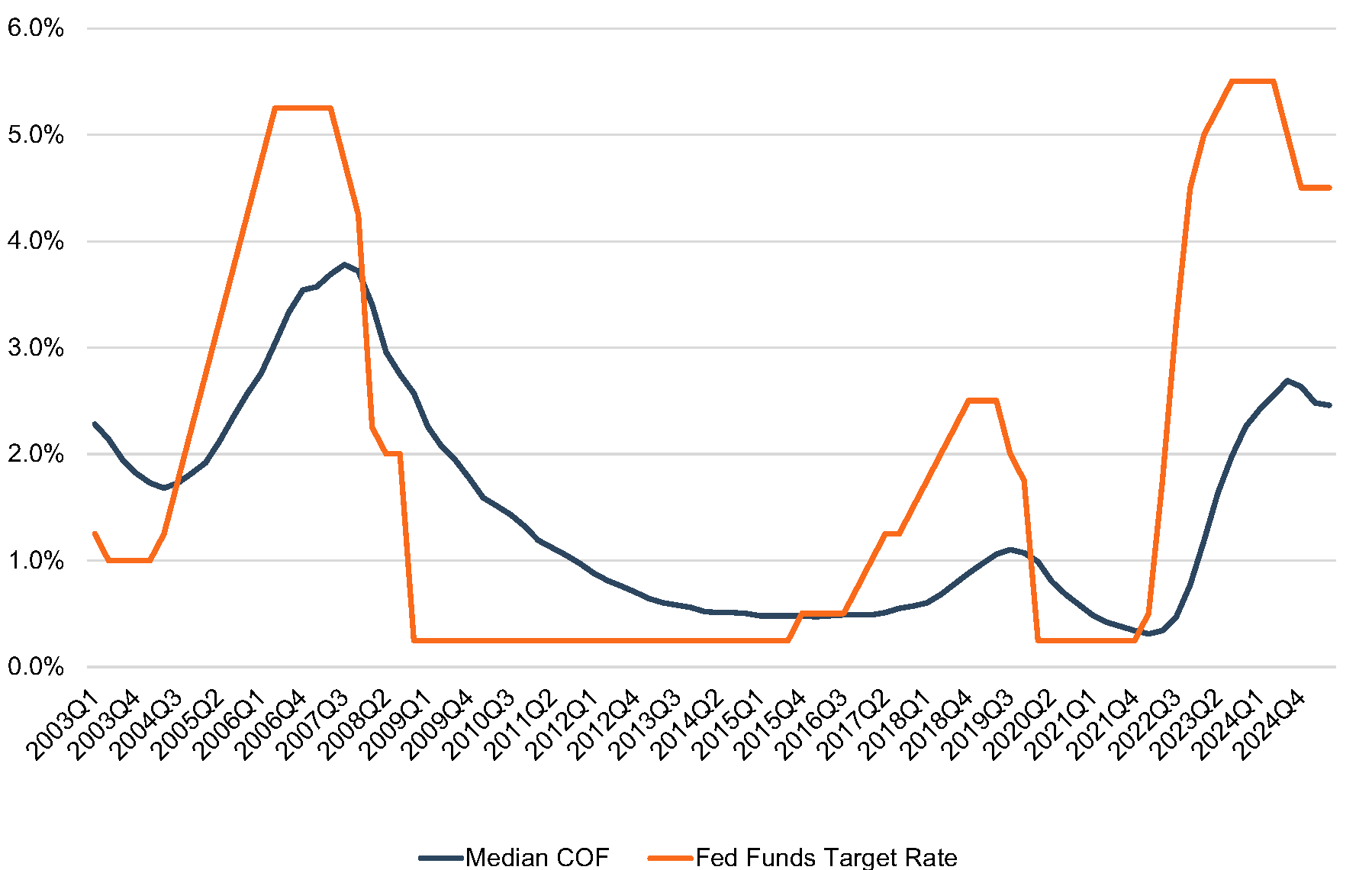

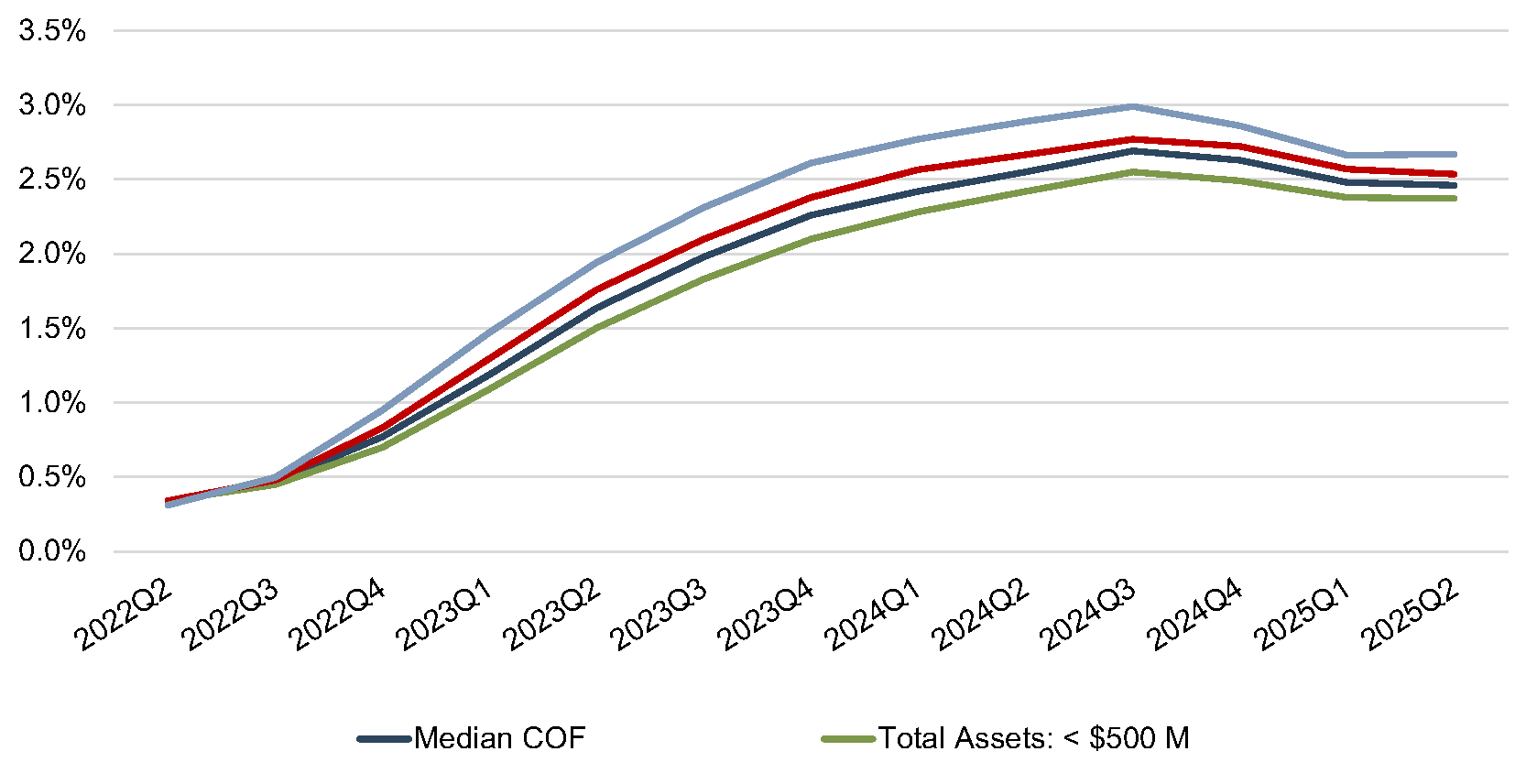

- Cost of Funds. Last year at this time, we expected that notifications of lower rates would trigger some depositors, who had become accustomed to higher rates, to seek alternatives. This would potentially limit a financial institution’s desire to reduce deposit rates given the need to preserve deposit balances. To the extent that a customer is particularly rate-sensitive, that account movement has likely already taken place, so there might be more room for downward movement in deposit rates. As shown on Figure 4, in falling rate environments, the median cost of funds has tended to decrease at a slower rate than the Fed Funds target rate. However, interest rate beta is in part determined by the size of the financial institution, as evidenced by Figure 5.

Figure 4 :: Median Cost of Funds as Compared to Target Federal Funds Rate

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

Figure 5 :: Cost of Funds by Asset Size – 2Q22 to 2Q25

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

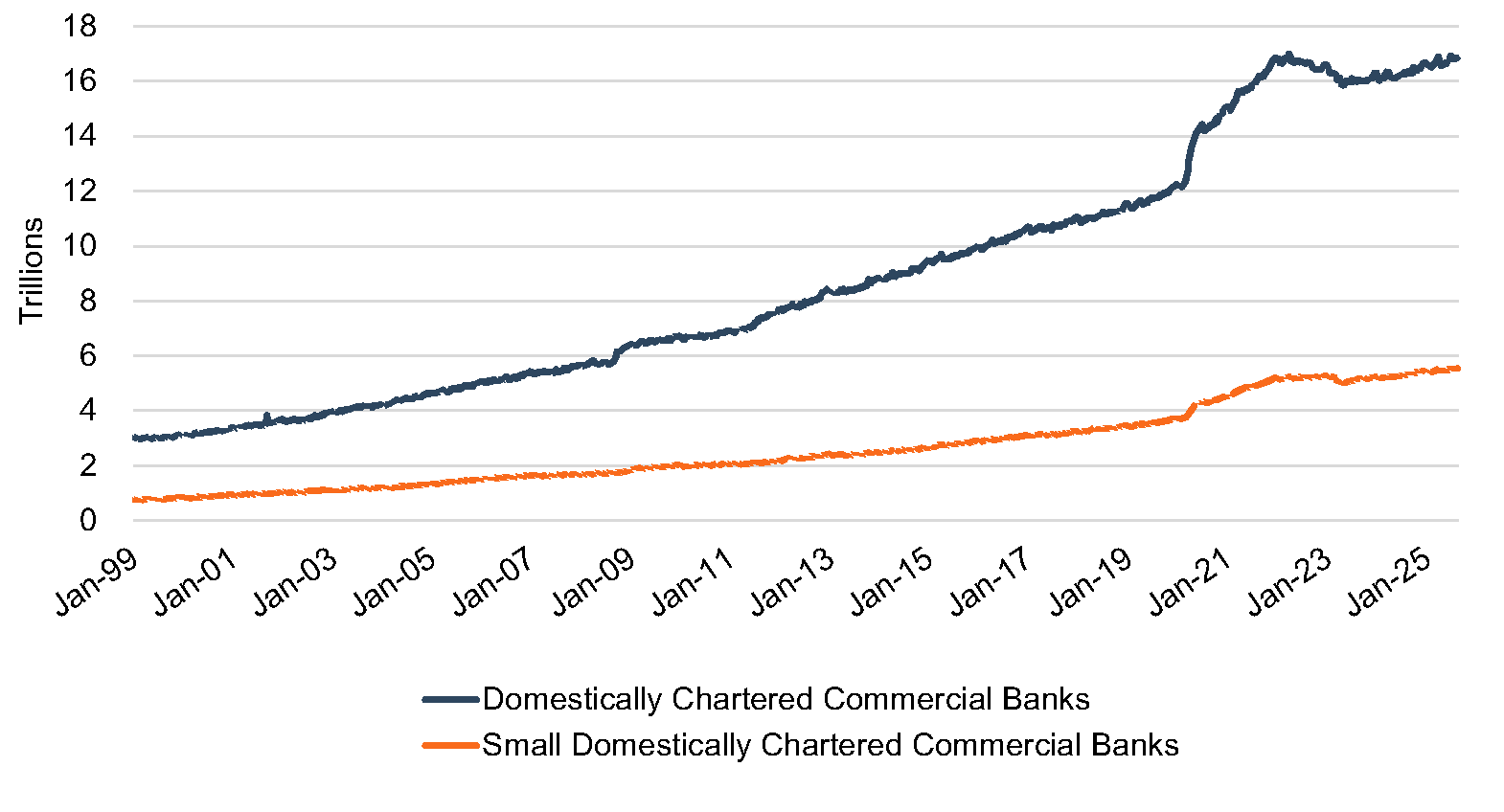

Figure 6 :: Total Industry Deposits Per Federal Reserve H.8 Release

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

- Deposit Levels. In 2022, total industry deposits fell 1.1%, the largest annual decline on record. Last year at this time, approximately half of respondents expected their organization’s deposits to increase between 1% to 5% over the next 12 months. This compares to the actual annual increase of 2.27% experienced by commercial banks during 2024. However, in the first and second quarters of 2025, deposits only increased modestly. In the same survey for the second quarter of 2025, over 80% of bankers expect deposits to grow over the next twelve months. All else equal, lower deposit runoff assumptions lead to higher indications of CDI value.

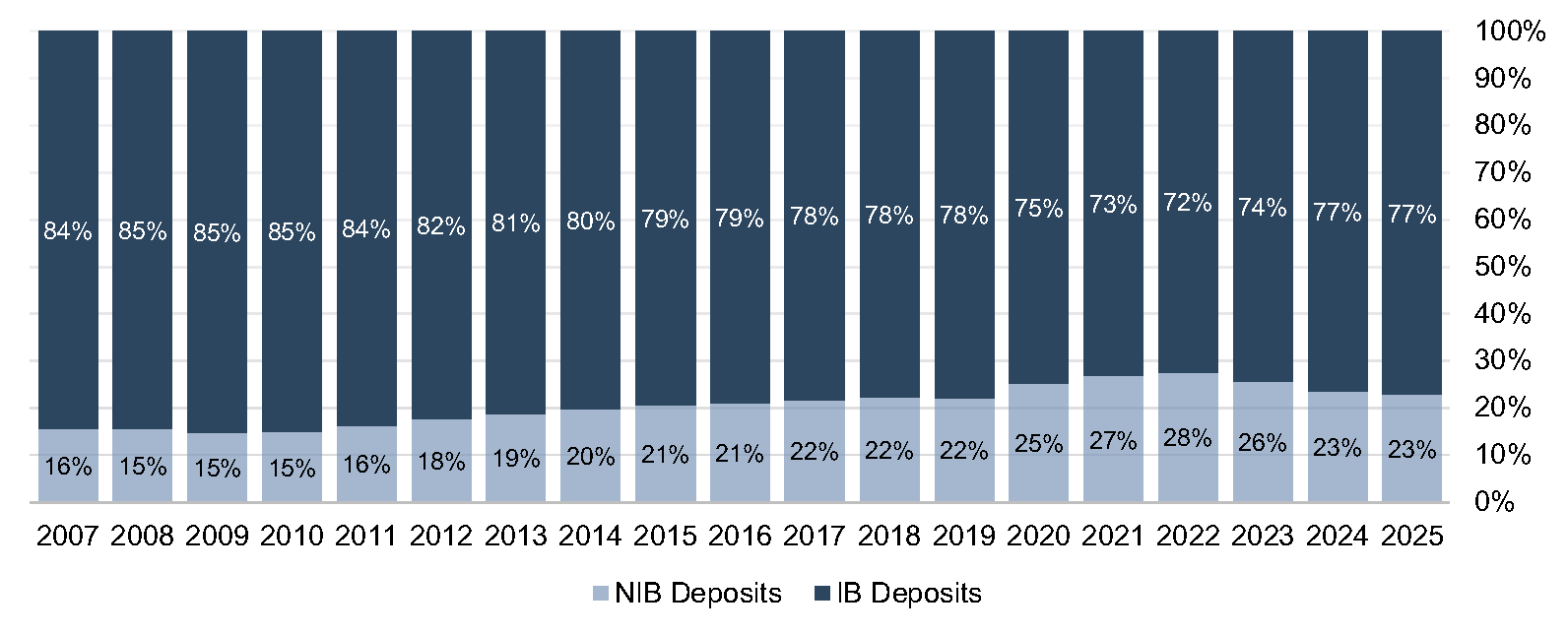

- Deposit Mix and Deposit Beta. Over the decade leading up to 2023, nationwide average deposit mix shifted in favor of noninterest bearing deposits. In 2023 through 2025, this trend began to reverse in a higher interest rate environment. However, the deposit mix shift toward interest bearing deposits might not continue in a falling interest rate environment. As noninterest-bearing deposits have higher CDI values, this could be a mitigating factor for the anticipated decline in CDI values.

- Uncertain Rate Outlook. The expectation is for lower rates, but the FOMC expressed concern related to both inflation and payroll data at the most recent meeting. The balancing act required to promote economic growth while mitigating inflationary pressures creates a murky view of the rate environment over the next couple of years.

Figure 7:: Deposit Mix Over Time

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

Trends In Deposit Premiums Relative To CDI Asset Values

Core deposit intangible assets are related to, but not identical to, deposit premiums paid in acquisitions. While CDI assets are an intangible asset recorded in acquisitions to capture the value of the customer relationships the deposits represent, deposit premiums paid are a function of the purchase price of an acquisition. Deposit premiums in whole bank acquisitions are computed based on the excess of the purchase price over the target’s tangible book value, as a percentage of the core deposit base.

While deposit premiums often capture the value to the acquirer of assuming the established funding source of the core deposit base (that is, the value of the deposit franchise), the purchase price also reflects factors unrelated to the deposit base, such as the quality of the acquired loan portfolio, unique synergy opportunities anticipated by the acquirer, etc. As shown in Figure 8, deposit premiums paid in whole bank acquisitions have shown more volatility than CDI values. Deposit premiums were in the range of 6% to 10% from 2015 to 2023, although this remained well below the pre-Great Recession levels when premiums for whole bank acquisitions averaged closer to 20%. Net interest margin pressure—caused by assets originated at low rates during the pandemic and deposits that proved more rate sensitive than expected—resulted in deposit premiums in 2024 falling to levels last seen in the Great Financial Crisis. That is, low cost core deposits proved valuable in 2024, but CDI values in whole bank transactions were diminished by mark-to-market adjustments on the asset side of the balance sheet, which also resulted from the higher rate environment. In 2025, net interest margin pressure has subsided, and deposit premiums have increased.

Figure 8 :: CDI Recorded vs. Deposit Premiums Paid

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

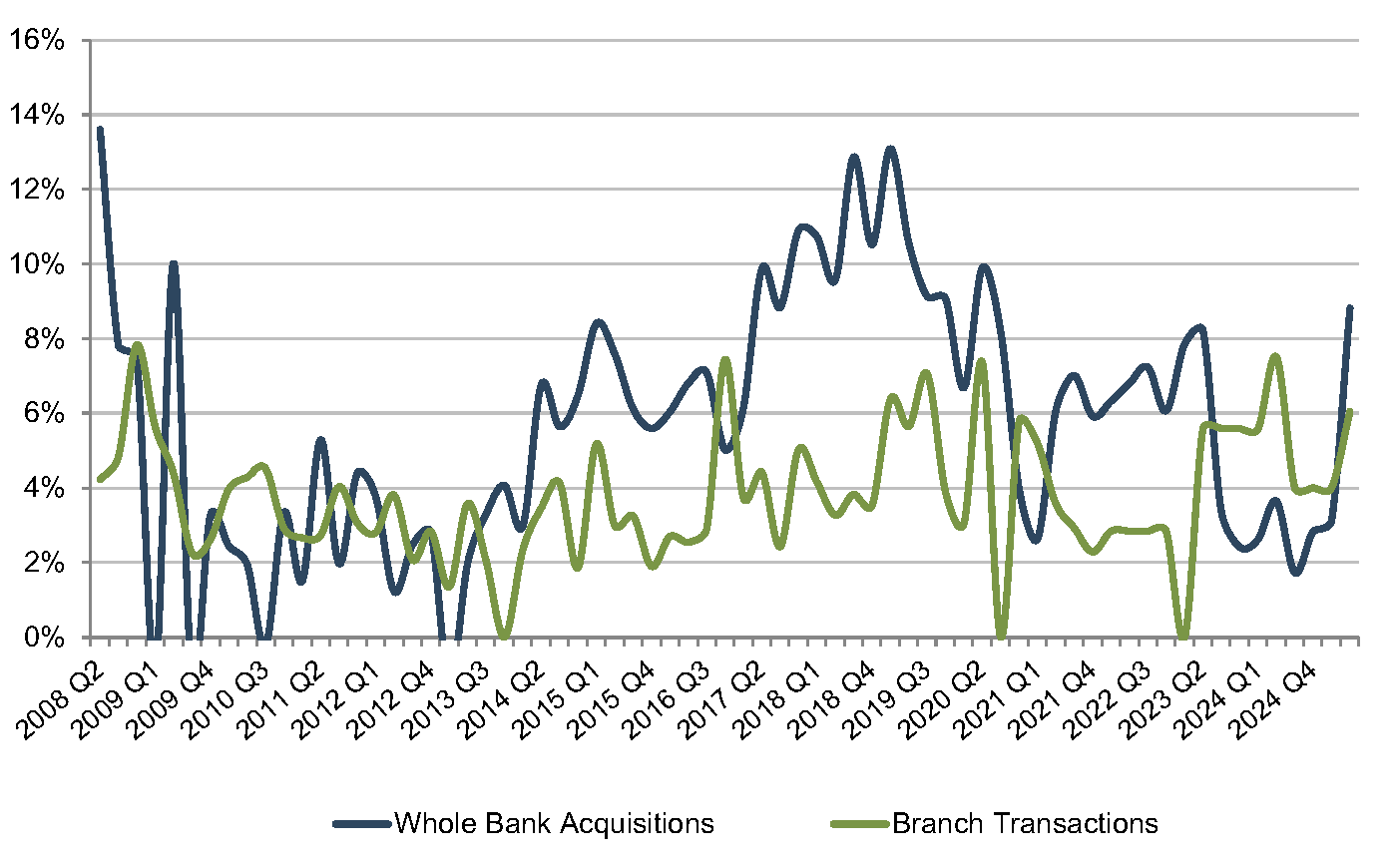

Additional factors may influence the purchase price to an extent that the calculated deposit premium doesn’t necessarily bear a strong relationship to the value of the core deposit base to the acquirer. This influence is often less relevant in branch transactions where the deposit base is the primary driver of the transaction and the relationship between the purchase price and the deposit base is more direct. Figure 9, on the next page, presents deposit premiums paid in whole bank acquisitions as compared to premiums paid in branch transactions.

Figure 9 :: Average Deposit Premiums Paid

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

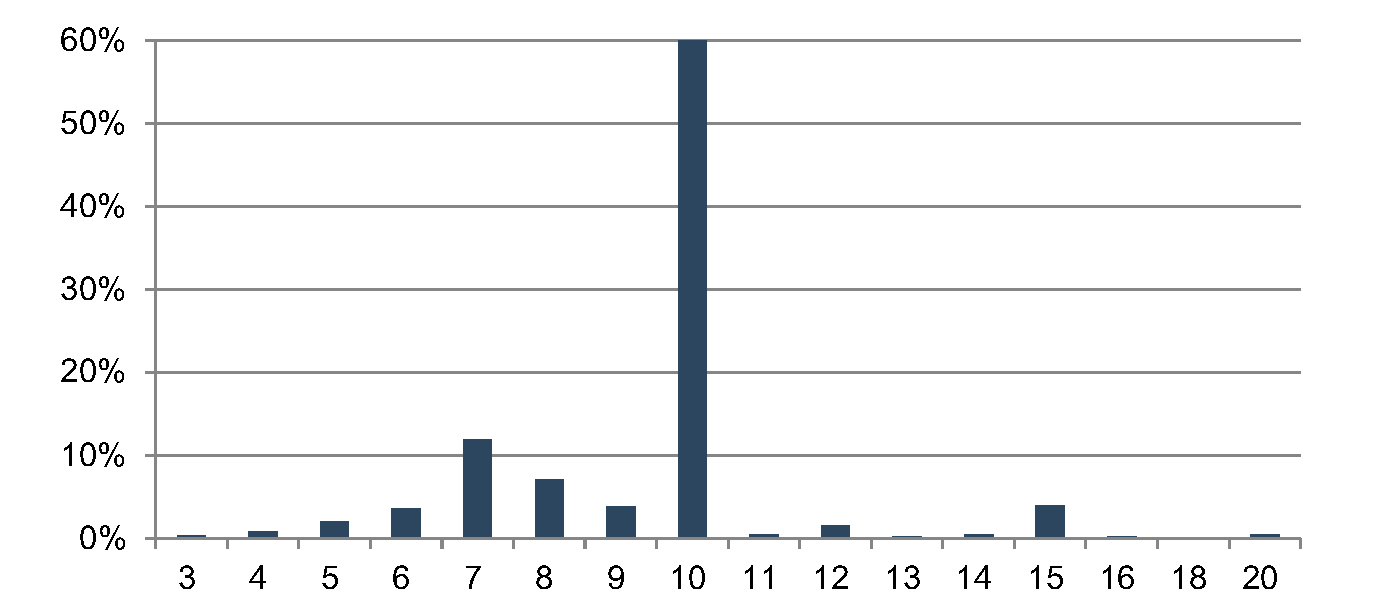

Figure 10 :: Selected Amortization Term (Years)

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

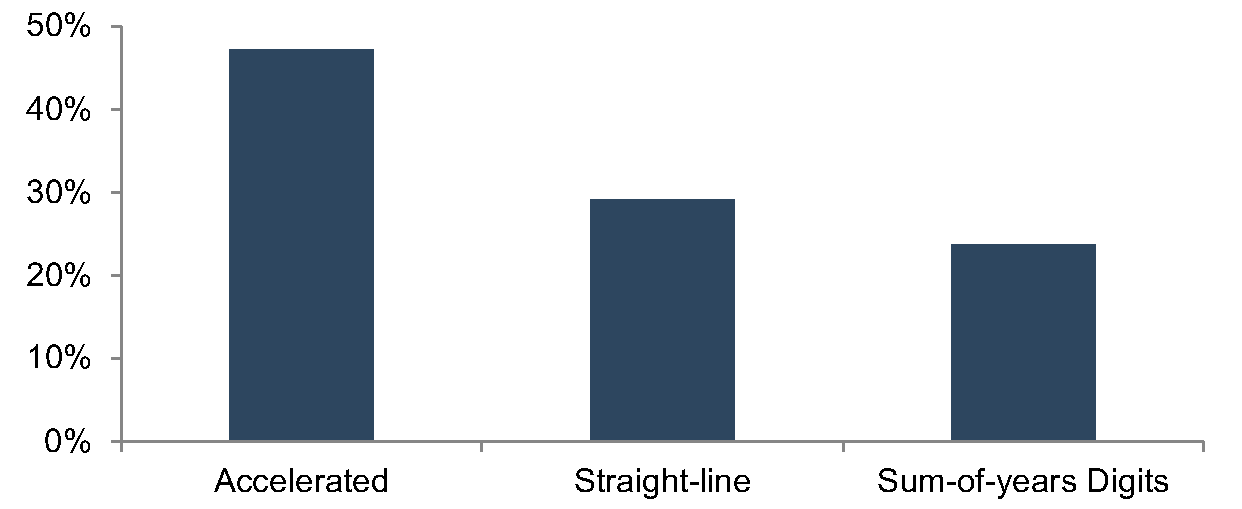

Figure 11 :: Selected Amortization Method

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence Cap IQ Pro

Deposit premiums paid in branch transactions have generally been less volatile than tangible book value premiums paid in whole bank acquisitions. Only three branch transactions with reported premium data have occurred year-to-date in 2025. For those transactions, the deposit premiums were 7.0%, 4.6%, and 7.5%. The same number of branch transactions with reported premium data occurred in 2024, and the premiums were similar. The lack of branch transactions, though, is indicative of their value. With high short-term funding costs and tight liquidity, few banks have been willing to part with stable, low cost core deposits.

Accounting For CDI Assets

Based on the data for acquisitions for which core deposit intangible detail was reported, a majority of banks selected a ten-year amortization term for the CDI values booked. Less than 10% of transactions for which data was available selected amortization terms longer than ten years. Amortization methods were somewhat more varied, but an accelerated amortization method, including the sum-of-the-years digits method, was selected in approximately two-thirds of these transactions.

Conclusion

Core deposit intangible values are influenced by many factors, and each institution’s deposit base is unique. Mercer Capital has deep experience analyzing CDI values and advising financial institutions in transactions and strategic decisions. Contact us to discuss how we can help your organization navigate these trends.

The Discount for Lack of Marketability in Divorce: When Should It Apply? – Part 1

During divorce proceedings, one of the most complex financial issues may be “what is the value of a business interest?” When the business is the single largest asset on the marital balance sheet, the complexities for division and income may be even larger. This is where business valuation experts assist the process. For non-controlling business interests, two of the significant debated valuation adjustments are the discount for lack of marketability (“DLOM”) and the discount for lack of control (“DLOC”, or together, “valuation discounts”). Whether valuation discounts apply depends not only on the facts and circumstances but also on the state laws where the divorce is filed.

What is a DLOM?

Simply put, a discount for lack of marketability reflects the concept that a business interest that cannot be readily sold is worth less than an investment that can be freely traded, like shares in a publicly traded stock.

By illustration: if you own 100 shares of Apple stock, you can sell them today with the click of a button. But if you own 25% of a family-owned construction company, finding a buyer for that 25% minority interest can be much more complicated. You may be subject to approvals or rights of first refusal by other owners, among other attributes or restrictions, that preclude swiftly selling your interests. The lack of a ready market reduces the attractiveness of the investment, and thus its value.

In business valuation, experts often apply a DLOM when valuing non-controlling interests in private companies. That is because majority stakes in private companies can often exercise some level of control to achieve liquidity. It is important for a business valuation expert to understand the company’s governance structure, among other considerations, and how that influences the marketability of the subject interest and therefore its valuation. As there is a range of possible discounts, the analyst reviews and analyzes various qualitative and quantitative attributes to support his/her concluded valuation discount(s).

Not all business valuation experts have experience valuing subject interests that are subject to minority and marketability discounts. These discounts are applicable in valuation scopes like transactions, shareholder matters, and estate/tax valuations. Fifteen years ago, the IRS published the Discount for Lack of Marketability Job Aid for IRS Valuation Professionals, which defined the DLOM, discussed the benefits and drawbacks of available methodologies at the time, and generally provided a framework for professionals when valuing for gift and estate tax purposes.

Some practitioners may bifurcate the various negative valuation influences of a discount for lack of control (such as the ability to compel a sale or dividends) rather than marketability. While this can be reasonably defended, it is important that practitioners do not double-count the same negative consequence in both a DLOC and DLOM, and some practitioners prefer to capture all of this in a single DLOM that considers all the factors.

Fair Value vs. Fair Market Value

The standard of value applied in a divorce valuation has ramifications, as seemingly identical terms have different implications. The specific definition for each term can vary depending on the context and the standard-setter or regulatory authority. Below, we provide definitions and explain how each standard of value impacts the applicability of a DLOM.

- Fair Market Value (“FMV”) can be defined as “the price at which the subject interest would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller when the former is not under any compulsion to buy and the latter is not under any compulsion to sell, both parties having reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts” (IRS Revenue Ruling 59-60, 1959-1 C.B. 237, Section 2.02). It is important to understand that under fair market value, the buyers and sellers are hypothetical parties and not the actual parties that own an interest.

Under the fair market value standard, valuation discounts are often considered because the discounted value reflects what an outside investor would likely pay. All else equal, prospective buyers of a minority interest want to be compensated for the uncertainty surrounding their future ability to sell that interest. - Fair Value (“FV”) can be defined as “the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date” (FASB ASC 820). In many jurisdictions, fair value is used in shareholder disputes and family law. Under this standard, courts frequently limit or even prohibit valuation discounts, reasoning that such discounts penalize the spouse who is not retaining the business interest.

Whether a state uses fair market value or fair value may determine whether valuation discounts are applicable in divorce. We note, however, that some states may have their own versions and/or definitions based on interpretation that do not directly correlate to the above definitions.

Examples of Jurisdictions That Allow (and Don’t Allow) a DLOM

It is important to understand the relevant statutes in the local jurisdiction, as states differ in their approach.

- New Jersey (No DLOM in Divorce): New Jersey courts have consistently rejected the application of a DLOM in marital dissolution cases. In Brown v. Brown (348 N.J. Super. 466, 2002), the Court held that applying such a discount would unfairly reduce the non-owner spouse’s equitable share. Because the business owner is not actually selling the interest, marketability is not deemed a real issue in the divorce context.

- Florida (DLOM Can Apply): In contrast, Florida courts have permitted DLOMs in some divorce valuations because the valuation should reflect the real-world limitations of a privately held business interest, even if no actual sale is taking place. From this perspective, ignoring the discount for lack of marketability inflates value beyond what the market would bear.

These examples show the importance of state statutes (or judicial interpretation of those statues). Two otherwise identical divorces can have very different outcomes depending on where they are filed. Furthermore, many cases are settled outside of the courts, and outside of any appeals process, providing further nuances to current considerations.

The Argument Supporting Application of a DLOM

Proponents of applying a DLOM in divorce assert that valuations should reflect economic reality. If a 25% stake in a private company couldn’t realistically be sold for “full” pro rata value in the open market, why should it be valued that way in a divorce?

From this perspective, not applying a DLOM creates an inflated conclusion of value that does not reflect the true financial worth of the marital interest. This could leave the owner-spouse saddled with an obligation (such as a buyout or cash settlement) based on an unrealistic valuation conclusion. A DLOM recognizes that private company stock isn’t as liquid as public stock.

The Argument Against Application of a DLOM

On the other hand, some assert that applying a DLOM unfairly harms the non-owner spouse. In most divorce cases, the owner isn’t actually selling the business interest. Instead, they continue to run the company and benefit from its cash flow.

Applying a DLOM in this situation results in a lower valuation and less economic benefit for the non-owner spouse. This may be especially problematic in cases where the business is the family’s largest marital asset. The underlying point of contention is: Why should the non-owner spouse bear a discount for a problem (marketability) that doesn’t actually exist in the divorce context? In other words, why assume a hypothetical sale when no such sale is contemplated?

Conclusion

In part 2, we will provide examples that demonstrate the real-world considerations that practitioners face in valuing non-controlling business interests in divorce.

Relative Total Shareholder Return Compensation

Trends, Challenges, and Valuation Considerations

Executive Summary

Relative total shareholder return (TSR) has become a central metric in long-term incentive plans, particularly for aligning executive compensation with shareholder outcomes. As companies navigate market volatility and evolving governance standards, a clear understanding of relative TSR-based awards is essential for effective plan design and regulatory compliance.

Definition and Mechanics

Relative TSR compensation typically involves performance-based equity awards—such as performance stock units (PSUs) or restricted stock units (RSUs)—that vest or pay out based on a company’s TSR performance relative to a defined peer group or market index over a specified period, commonly three years. TSR reflects stock price appreciation plus reinvested dividends, offering a comprehensive measure of shareholder value creation.

Unlike absolute TSR, which evaluates a company’s standalone performance, relative TSR benchmarks performance against peers. This structure is intended to reward outperformance regardless of broader market conditions. For example, executives may earn 150-200% of the target award for top-quartile performance, while below-median results may result in no payout. Under ASC 718, these awards are classified as market-condition grants, requiring fair value measurement at the grant date without subsequent adjustment for performance outcomes. Common design features include interpolation between performance thresholds, discrete payout levels, and caps for negative absolute TSR. As we have previously discussed, new proxy disclosure rules implemented in 2022 brought greater attention to these types of plans and awards.

Adoption Trends

Relative TSR has seen widespread adoption among U.S. public companies. In 2024, over 70% of S&P 500 companies granted PSUs tied to relative TSR, a significant increase from prior decades. Some companies also use hybrid models that combine TSR with financial metrics such as earnings per share (EPS) or return on invested capital (ROIC). Adoption rates among smaller companies remain lower (40–50%), often due to challenges in peer group selection and valuation.

For a summary of the changes and SEC commentary following the first year of pay versus performance on relative TSR plans, see our prior article on the topic.

Implementation Challenges

Despite its advantages, relative TSR presents several design and operational challenges:

- Peer Group Selection: Identifying appropriate comparable companies is complex and subject to scrutiny. Differences in industry, size, or business model can distort outcomes. Peer group changes due to mergers, acquisitions, or delistings require ongoing updates.

- Market Sensitivity: TSR can be affected by external factors beyond management’s control. High relative rankings may occur despite negative absolute returns, raising concerns about fairness.

- Negative TSR Caps: Without caps, awards may vest at high levels even when shareholders experience losses. Many plans now include caps (e.g., limiting payouts to 100% if TSR is negative).

- Accounting and Disclosure: ASC 718 prescribes grant-date fair value recognition, which

typically requires the use of Monte Carlo simulation. Disclosure complexity and potential SEC scrutiny may add to the administrative burden. - Proxy and Shareholder Oversight: Poorly designed plans may face negative say-on-pay votes. Proxy advisors penalize plans with low rigor or excessive payouts, prompting companies to enhance design robustness.

Valuation Considerations

Valuing relative TSR awards typically involves Monte Carlo simulation, which models thousands of potential stock price paths for the company and its peers. This method incorporates volatility, correlation, and dividend assumptions to estimate fair value at grant.

Key steps include:

- Input Collection: Gather historical stock returns, risk-free rates, and peer correlations.

- Simulation: Project stock paths using stochastic models such as geometric Brownian motion.

- Payout Calculation: Determine TSR rankings for each path and apply the plan’s payout scale.

- Fair Value Estimation: Calculate the average discounted payout across simulations to determine fair value.

- Tests of Reasonableness: Sensitivity analyses are often used to assess the impact of changes in key assumptions.

U.S. GAAP (ASC 718) requires Monte Carlo simulation for awards with market conditions, especially when payout structures are non-linear or include caps. Monte Carlo simulation requires technical expertise to implement, and inaccurate inputs or flawed modeling can lead to distorted compensation expense and misleading proxy disclosures.

Implications and Key Takeaways

Relative TSR remains a widely adopted mechanism for aligning executive pay with shareholder outcomes. Its effectiveness depends on thoughtful plan design, including:

- Selecting relevant and stable peer groups

- Incorporating safeguards such as caps on negative TSR

- Applying robust valuation methodologies

As market conditions evolve, companies should regularly review and adjust their compensation frameworks to maintain alignment with governance expectations and shareholder interests.

How Mercer Capital Can Support

Mercer Capital provides specialized valuation services for equity-based compensation, including relative TSR awards under ASC 718. Our team offers independent fair value assessments, Monte Carlo simulations, and strategic guidance on plan design and peer benchmarking. Contact Mercer Capital to learn how we can support your financial reporting and executive compensation strategies.

Navigating Business Valuations During Active M&A Processes: Critical Considerations for Estate Planners

Executive Summary

This article summarizes Mercer Capital’s whitepaper, Valuing a Business for Estate Planning Purposes During a Transaction, which addresses the complex intersection of business valuations and estate planning when M&A processes are underway.

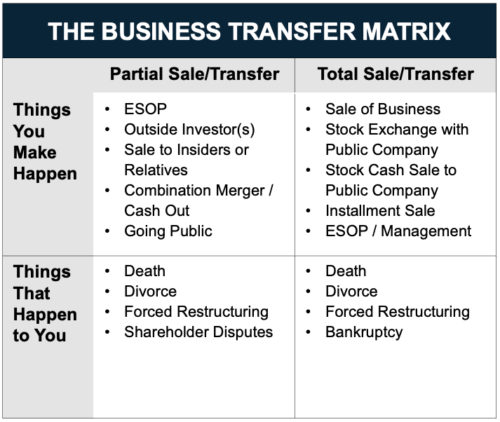

Estate planning for business owners becomes much more complicated when a merger or acquisition process is underway. IRS guidance suggests requirements that business valuations for transfer tax purposes must consider all knowable facts as of the valuation date—including pending transaction processes. This creates both opportunities and risks for estate planners working with clients who own businesses actively engaged in sale discussions.

The challenge lies in determining how much weight to assign to potential deal proceeds versus traditional standalone valuations at different stages of the M&A process. While early-stage processes may warrant minimal consideration of transaction value, later stages with formal offers require greater weighting of expected proceeds. Understanding the nuances of an engagement of this type is essential for avoiding costly mistakes and ensuring credible valuations that optimize estate planning outcomes.

The intersection of business transactions and estate planning presents one of the most complex challenges in wealth transfer strategies. When business owners—whose enterprises often represent the majority of their wealth—simultaneously pursue exit opportunities and engage in estate planning, the valuation considerations become particularly intricate and consequential.

IRS Chief Counsel Advice 202152018

In Chief Counsel Advice 202152018 (“CCA 202152018”), the IRS addressed two issues in the context of a business owner who funded a GRAT during an active sale process. First, it considered whether hypothetical willing buyers and sellers would take into account a pending merger when valuing stock for gift tax purposes. The Service answered affirmatively: under the fair market value standard, known or knowable facts—including an ongoing sale process and offers already received—must be incorporated into valuation. Second, the IRS considered whether the donor retained a “qualified annuity interest” under §2702 when the GRAT was funded using a stale §409A appraisal that ignored the pending merger. The Service held that the retained interest failed to qualify, treating the entire transfer to the GRAT as a taxable gift.

The facts of the case reveal a pattern of valuation inconsistencies. The taxpayer used a seven-month-old §409A appraisal—prepared for deferred compensation purposes, not transfer tax purposes—to support the GRAT funding, even though multiple offers had already been received at higher prices. Shortly thereafter, however, the same taxpayer funded a charitable remainder trust using a contemporaneous qualified appraisal that reflected the higher offer price. This inconsistency, coupled with reliance on an outdated and contextually inappropriate appraisal, invited IRS scrutiny and resulted in the Service’s determination that the GRAT was fatally flawed.

While CCAs do not carry precedential weight, they are instructive of how the IRS is likely to approach similar fact patterns. CCA 202152018 signals heightened IRS vigilance where GRATs or other transfer tax strategies are executed amidst an ongoing or foreseeable liquidity event. It highlights the necessity of contemporaneous, purpose-appropriate appraisals that consider all relevant facts at the valuation date. Failure to do so risks not only valuation adjustments but also possible disqualification of retained interests under §2702, leading to the result of treating the entire transfer as a taxable gift.

Understanding the M&A Process Framework

To properly value businesses during transaction processes, estate planners must understand the typical stages of mergers and acquisitions. The process generally unfolds through six distinct phases, each presenting different levels of transaction certainty and information availability.

During the planning phase, when owners hire M&A advisors and organize information, there may be little quantifiable expectation of proceeds. However, once confidential information memorandums are distributed to potential buyers, expectations around selling prices become clearer. As the process progresses through qualification phases with indications of interest, buyer selection with letters of intent, due diligence, and final negotiations, the probability of completion and the certainty of proceed size generally increase.

The critical insight for estate planners is that valuation weight should shift toward transaction proceeds as deal certainty increases. A business in early marketing phases might warrant only modest consideration of potential proceeds, while a company with binding letters of intent is more likely to merit substantial weighting of expected transaction value.

Market Reality of Deal Success and Failure

Understanding transaction success rates provides crucial context for valuation decisions. In a McKinsey & Company analysis of over 2,500 large deals valued above €1 billion, approximately 10.5% of deals were canceled, with larger transactions facing higher failure risks. Deals exceeding €10 billion experienced cancellation rates above 20%, while those under €5 billion maintained consistent 10% annual cancellation rates.

In this analysis, industry factors significantly impacted success probability. Energy and financial sector deals showed the lowest cancellation rates at around 7%, while consumer discretionary and communications services faced higher failure rates of 13% and 19% respectively. Nearly 75% of canceled deals failed due to price expectations, regulatory concerns, or political issues.

However, these statistics apply primarily to publicly announced transactions, making them most relevant for closely held companies in later deal stages. Earlier-phase failures often remain private, suggesting estate planners should shift weight toward no-sale scenarios when businesses are in preliminary transaction stages.

Critical Success Factors

Several factors influence deal completion probability and should inform valuation weightings. Expected deal timelines matter significantly—longer processes face higher failure rates. Deal structure complexity creates additional risk, as mixed cash-and-stock transactions prove less successful than simpler all-cash or all-stock arrangements.

The number and quality of bidders affect completion likelihood. Multiple interested parties provide fallback options, though this dynamic can shift if secondary bidders lose interest. More sophisticated bidders, such as private equity firms or strategic acquirers with dedicated M&A teams, typically conduct more thorough early evaluation but also identify issues that might derail transactions.

External factors including economic conditions, political stability, and regulatory environment all influence completion probability. Companies with clean financial records, predictable cash flows, and minimal discretionary items in recent results face higher completion probabilities due to reduced due diligence risks.

The Levels of Value

Business owners and their professional advisors are occasionally perplexed by the fact that their shares can have more than one value. This multiplicity of values is not a conjuring trick on the part of business valuation experts, but simply reflects the economic fact that different markets, different investors, and different expectations necessarily lead to different values.

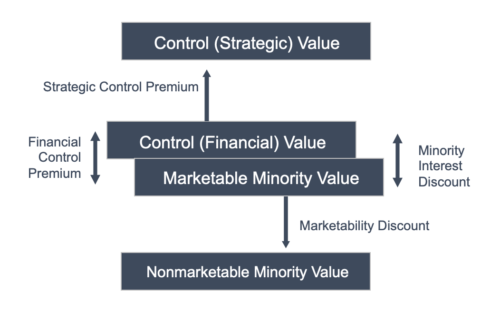

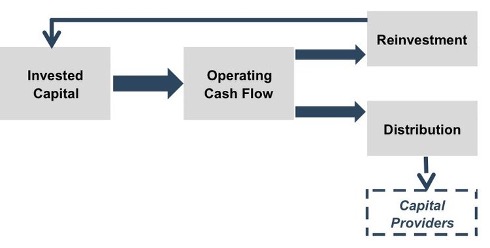

Business valuation experts use the term “level of value” to refer to these differing perspectives. As shown in the figure below, there are three basic “levels” of value for a business.

Estate planning transfers typically involve minority interests valued at the nonmarketable minority level, which may incorporate discounts for lack of control and marketability. In contrast, M&A transactions occur at control levels and may include strategic premiums for synergies.

This creates significant value gaps. A business with $100 per share marketable minority value might be valued at $65 per share for estate planning purposes after appropriate discounts. However, strategic buyers might pay $130 per share, creating a substantial differential between transfer values and transaction proceeds.

Understanding Deal Proceeds

Expected transaction proceeds require careful analysis beyond headline multiples. Deal terms may include earn-outs, contingent payments, or non-cash consideration that should be risk-adjusted and converted to cash equivalency. The proposed transaction could trigger corporate-level taxes that would need to be considered in valuing an equity interest. A transaction appearing to price at 12x EBITDA might only deliver 9x value on a cash-equivalent basis after considering payment timing, corporate taxes, and performance risks.

Practical Application Framework

Estate planners working with businesses in transaction processes should expect valuation frameworks that appropriately weight no-sale scenarios against expected proceeds based on process stage and specific circumstances.

As transaction processes progress through marketing phases with distributed information memorandums, modest weighting of expected proceeds becomes appropriate, though determining precise allocations requires careful analysis of company-specific factors and buyer interest levels.

Once formal indications of interest are received, increasing weight is likely to shift toward transaction proceeds, with the specific allocation depending on offer quality, buyer sophistication, and deal structure. By the time binding letters of intent are executed, substantial weighting of expected proceeds is typically warranted, though some consideration of failure scenarios remains appropriate until closing occurs.

Compliance and Documentation Requirements

The IRS guidance emphasizes that valuations should ideally use valuation dates matching transfer dates and consider all knowable facts. Using outdated appraisals prepared for other purposes creates significant compliance risks, particularly when those appraisals ignore ongoing transaction processes. Business appraisers should document their consideration of transaction processes and provide clear rationale for their weighting decisions.

Strategic Implications for Estate Planning

Understanding these dynamics enables more effective estate planning strategies. Business owners contemplating both exit strategies and wealth transfer can time their planning to optimize valuations while maintaining compliance. Earlier transfers in transaction processes may capture lower valuations, though this must be balanced against deal completion risks and the potential for significant value increases.

The complexity of these valuations underscores the importance of engaging qualified professionals who understand both IRS transfer tax requirements and M&A market dynamics. Estate planners need valuation specialists who can navigate the technical requirements while providing credible opinions that optimize client outcomes.

Conclusion

The intersection of business transactions and estate planning presents both opportunities and pitfalls for wealth transfer strategies.

Success in this complex environment requires understanding M&A process stages, deal success factors, valuation methodologies, and compliance requirements. Estate planners who understand these concepts can help business owners navigate simultaneous exit and wealth transfer strategies while avoiding the costly mistakes that have drawn IRS scrutiny.

The stakes are significant—business interests often represent the majority of owner wealth, making proper valuation essential for effective estate planning. With careful planning, appropriate professional guidance, and an understanding of regulatory guidance, these complex situations can be managed successfully to achieve both transaction and estate planning objectives.