Creativity in Financial Elements of a Collaborative Divorce

This presentation was delivered by Scott A. Womack, ASA, MAFF and Cheryl C. Panther, CPA/PFS, ADFA/CDFA (Panther Financial Planning) 19th Annual Networking and Educational Forum hosted by the International Association of Collaborative Professionals.

This session, “Creativity in Financial Elements of a Collaborative Divorce,” is described below.

Financial creativity is not just for financial professionals. We will highlight actual case examples of how to strategically and efficiently use outside professionals and unique ways to utilize financial information. We’ll provide ideas that professionals from all disciplines can take back to their local practice groups.

Lifestyle / Pay & Need Analysis

This presentation was delivered by Karolina Calhoun, CPA/ABV/CFF at the AICPA 2018 Forensic & Valuation Services Conference.

Learning objectives include:

- Identify and Classify Assets & Liabilities to include on marital and separate balance sheets:

- Examine documentation and accuracy of the support

- Assemble relevant information:

- Current accounts (bank, brokerage) vs long-term compensation accounts (401k, pensions, etc.)

- Evaluate monthly budget for each spouse:

- Compare/contrast spouse’s budgets

- Evaluate the payor’s ability to support and the payee’s need for support:

- Lifestyle analysis comes into play here as the historical expenses may be used as a basis for monthly budget, however, depending on the finances, may or may not be supported post-divorce

- Lifestyle analysis also provides the ability to measure the division of net worth at date of divorce and future net worth accumulation over time

2019 Outlook: Gasping for Air Replaces 2018’s Rainbow Chasing

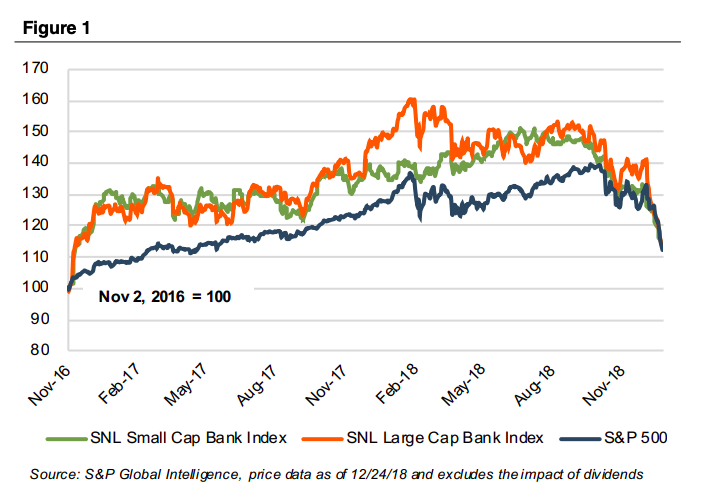

What a difference a year makes. A year ago corporate tax reform had been enacted that lowered the top marginal tax rate to 21% from 35%. Banks were viewed as one of the primary beneficiaries through a reduction in tax rates and a pick-up in economic growth. Now investors are questioning whether bank stocks and other credit investments are canaries in the U.S. economic coalmine.

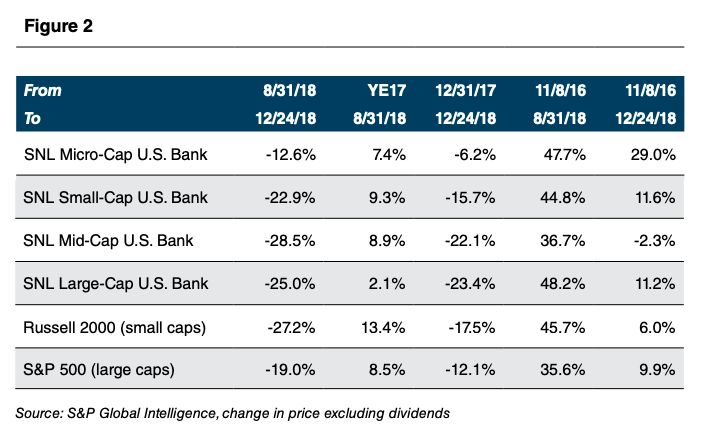

As 2018 draws to a close, bank fundamentals are very good; however, bank stock prices have tanked. SNL Financial’s small-, mid-, and large-cap bank indices have fallen by more than 20% since August 31, which meets the threshold definition of a bear market (i.e., down 20% vs. 10% for a correction).

Markets, of course, lead fundamentals, and corporate credit markets lead equity markets. Among industry groups, bank stocks are “early cyclicals”, meaning they turn down before the broader economy does and tend to turn up before other sectors when recessions bottom.

Large cap banks peaked in February while the balance of the industry peaked in the third quarter after having a fabulous run that dates to the national elections on November 8, 2016. The downturn in bank stock prices corresponds with weakening home sales, widening credit spreads in the leverage loan and high yield bond markets, a ~40% reduction in oil prices, and a nearly inverted Treasury yield curve.

To state the obvious: markets—but not fundamentals so far—are signaling 2019 (and maybe 2020) will be a more challenging year than was assumed a few months ago in which the economy slows and credit costs rise. The key question for 2019 then is: how much and is a slowdown fully priced into stocks?

Our next issue of Bank Watch will entail a deep dive into credit, but for this issue, we observe that a global unwind of leverage is underway as the Fed extracts liquidity from the system. Bond buying (QE) and ultra-low rates helped drive asset prices higher. The reverse is proving true, too.

Bank Fundamentals

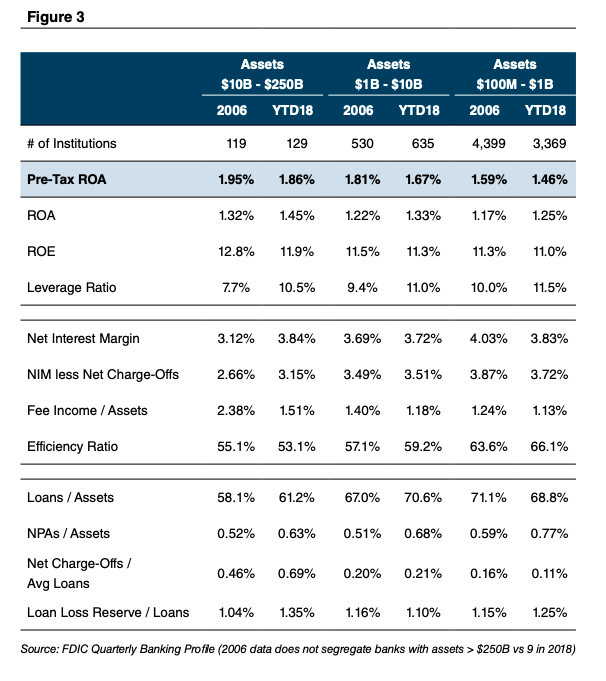

Bank fundamentals are in good-to-great shape. During the third quarter all FDI-Cinsured institutions reported aggregate net income of $62 billion, up 29.3% from 3Q17. Excluding the impact of lower taxes, 3Q18 pro forma net income would have been about $55 billion, up 13.9% from 3Q17. The data is more nuanced once the industry is segregated by asset size, however.

As shown in Figure 3, ROA and ROE have nearly rebounded to the last pre-crisis year of 2006. Importantly, capital has increased significantly and, thereby, provides an additional buffer whenever the next downturn develops.

As it relates to 2019, bank fundamentals are not expected to change much other than credit costs are expected to increase from a very low level in which current loss rates in all loan categories are below long-term averages. Wall Street consensus EPS estimates project mid-single digit EPS growth for the largest banks, primarily as a result of share repurchases and a slightly higher full year NIM, while regional and community bank consensus estimates reflect upper single digit EPS growth from the same factors and somewhat better loan growth.

However, credit and equity markets imply the consensus is too high given the sharp widening in credit spreads and drop in bank stock prices the past several months. Although markets lead fundamentals, market signals about magnitude are less clear. Given continuing growth in the U.S. economy that on balance will be helped by lower oil prices, it seems reasonable that an increase in credit costs the market is forecasting will be modest, and as a result, bank profitability will not be meaningfully crimped in 2019.

The Fed: 2019 Rate Hikes Seem Unlikely

Whenever the Fed embarks on an extended rate hiking campaign, the saying goes the Fed hikes until something breaks. The market is signaling that the December rate hike—the ninth in the current cycle—that pushed the Fed Funds target from 2.25% to 2.50% when the yield on the 10-year UST bond was ~2.8% may be one of those moments. What’s unusual about the current tightening cycle is it represents an attempt by the Fed (but not the BOJ, ECB or SNB) to extract itself from radical monetary policies in which the Fed is raising short-term rates and shrinking its balance sheet at the same time.

Given the flat yield curve, it is hard to see how the Fed will hike the Fed Funds another couple of times as planned for 2019, unless the Fed wants to invert the yield curve or unless intermediate- and long-term rates reverse and trend higher. Presumably the $50 billion a month pace in the reduction of its US Treasury and Agency MBS portfolio will continue. Alternatively, perhaps the Fed will bow to the market and not raise rates in 2019 and slow or even halt the reduction in its balance sheet to stabilize markets.

As it relates to bank fundamentals, the impact on net interest margins will depend upon individual bank balance sheet compositions. Broadly, however, a scenario of no rate hikes implies less pressure to raise deposit rates, and rising wholesale borrowing rates should stabilize. The result, therefore, should be a little bit better NIMs than a slight reduction if the Fed continues to hike given that deposit rate betas for many institutions are well over 50% now. More important for banks if the Fed pauses vs continues to hike would be the impact on asset values (higher all else equal) and, therefore, credit costs.

Bank Valuations: Support but Never a Stand-Alone Catalyst

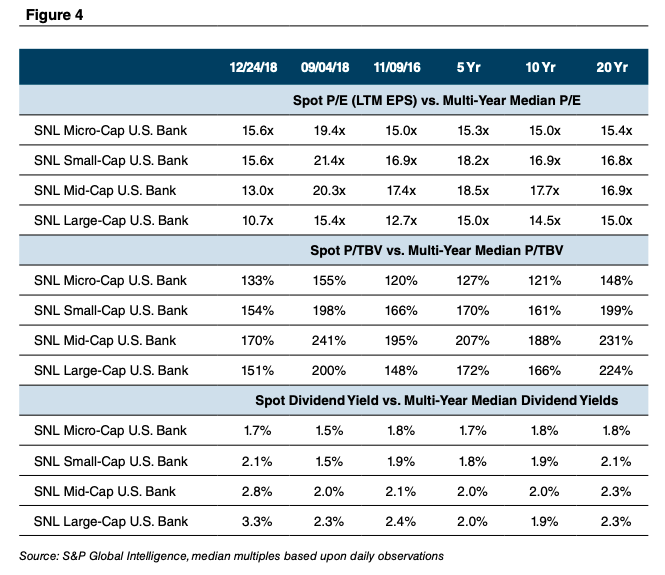

A synopsis of bank valuations is presented in Figure 4 in which current valuations for the market cap indices are compared to the approximate market top around August 31, November 8, 2016 when the national election occurred, and multi-year medians based upon daily observations. An important point is that valuation is not a catalyst to move a stock; rather, valuation provides a margin of safety (or lack thereof) and thereby can provide additional return over time as a catalyst such as upward (or downward) earnings revisions can cause a multiple to expand or contract.

Bank stocks—particularly mid-cap and large-cap banks—enter 2019 relatively inexpensive to history. The stocks are cheap relative to 2019 consensus earnings with large cap banks trading around 8x and small cap banks at 10x; however, the market’s message is that the estimates are too high. It is hard to envision that estimates are dramatically too high as proved to be the case in 2008 unless the economy is poised to roll-over hard, which seems unlikely. Assuming no recession or a shallow recession, then, the modest valuations may result in bank stocks having a good year even if fundamentals weaken and analysts cut estimates because the limited downside in earnings had been adequately priced into the stocks by late December.

Bank M&A: Slowing Activity for 2019 Likely

Outwardly, 2018 has been another good year for bank M&A even though activity slowed in the fourth quarter. There were few notable deals other than Fifth Third’s pending acquisition of Chicago-based MB Financial valued at $4.8 billion at announcement and Synovus Financial’s pending acquisition of Boca Raton-based FCB Financial Holding valued for $2.8 billion at announcement. Even before bank stocks rolled over the shares of both Fifth Third and Synovus severely underperformed peers as investors questioned the exchange ratios, cost saving assumptions, credit risk (especially at FCB), and whether the buyers could keep the franchises intact as key personnel defected elsewhere.

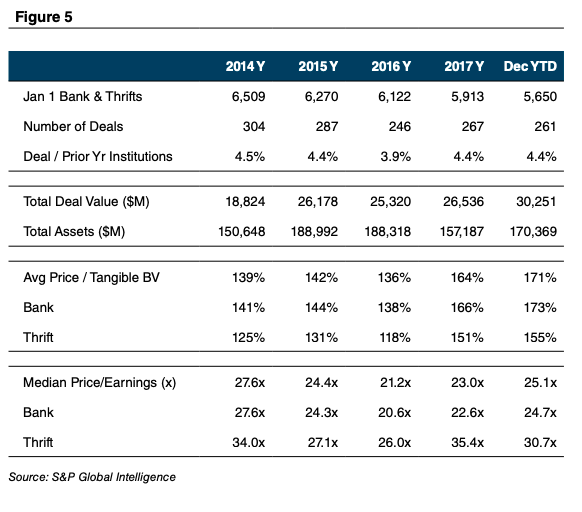

The national average price/tangible book multiple expanded to 173% from 166% in 2017 and about 140% in 2014, 2015 and 2016 before the sector was revalued in the wake of the national election. The median P/E of 25x was within the five-year range of 21x to 28x.

The total number of bank and thrift transactions through December 24 totaled 261, which equated to 4.4% of the commercial bank and thrift charters as of year-end 2017. During 2014–2018, the number of acquisitions exceeded 4% each year except for 2016 when activity at the beginning of the year was hampered by weak stock prices as a result of a slowing economy that was marked by a collapse in oil prices and sharply wider credit spreads.

Weak bank stock prices crimp the ability to negotiate deals because most sellers are focused on absolute price rather than relative value when taking the buyer’s shares as consideration; and, buyers usually are unwilling to increase the number of shares being offered given a limitation on minimum acceptable EPS accretion and maximum acceptable TBVPS dilution. A notable late year exception occurred when Cadence Bancorporation opted to increase the number of shares it will issue to State Bancorp by 9.6% because the double trigger in the merger agreement signed during May when Cadence’s share price was much higher came into play.

Although there is no change in the driver of consolidation such as succession issues, shareholder liquidity needs, and economies of scale, a slowdown in M&A activity in 2019 is likely because bank stocks will enter the year depressed. Deals that entail some amount of common share consideration will be tough to structure unless sellers will be willing to take less, which most will not do with operating fundamentals in good shape for now. All cash deals will be impacted less, but all cash deals are more prevalent among very small institutions in which pricing usually occurs at a discount to those that entail some proportion of common shares.

Summing It Up

The market is shouting fundamentals will weaken in 2019 after a long period of gradual improvement following the Great Financial Crisis, which most likely will be reflected in sluggish loan growth and modestly higher credit costs; however, bank stocks may surprise to the upside as they did to the downside in 2018 provided a) there is no recession or a shallow one; and, b) the Fed relents and does not hike further and potentially slows the run-off of its excess bonds (and liability reserves). For clients of Mercer Capital who obtain year-end valuations, rising stock prices since the presidential election may be reversed partially, given the compression in market price/earnings and price/tangible book value multiples that occurred in 2018.

Adjusted Earnings and Earning Power as the Base of the Valuation Pyramid

The extensive use of core versus reported earnings by public companies has been a widespread phenomenon for at least 25 years. During the past decade, the practice also has become widespread among companies (and their bankers who market deals) that are issuing debt in the leverage loan and high yield markets.

The practice is controversial. The SEC periodically will crack down on companies it thinks are pushing the envelope. Bank regulators have raised the issue of questionable adjustments to borrowers’ EBITDA for widely syndicated leverage loans.

Investors are aware of the issue, too, but have not demanded the practice to stop. In mid-2017, I attended a conference on private credit. One session dealt exclusively with adjusted EBITDA. One panelist offered that adjustments in the range of 5-10% of reported EBITDA were okay, but the consensus was the adjustments were out of control. Covenant Review reported that as of mid-2017 the average leverage for middle market LBOs over the prior two years was 5.5x based upon the target’s adjusted EBITDA compared to reported EBITDA of ~7x. The issue is no better, and perhaps worse, in 2018 judging from market sentiment.

If investors are solely relying upon company defined adjusted EBITDA, then they may be vacating their fiduciary duties when investing capital. That said, an analysis of core versus reported earnings is a critical element of any valuation or credit assessment of a non-early stage company with an established financial history.

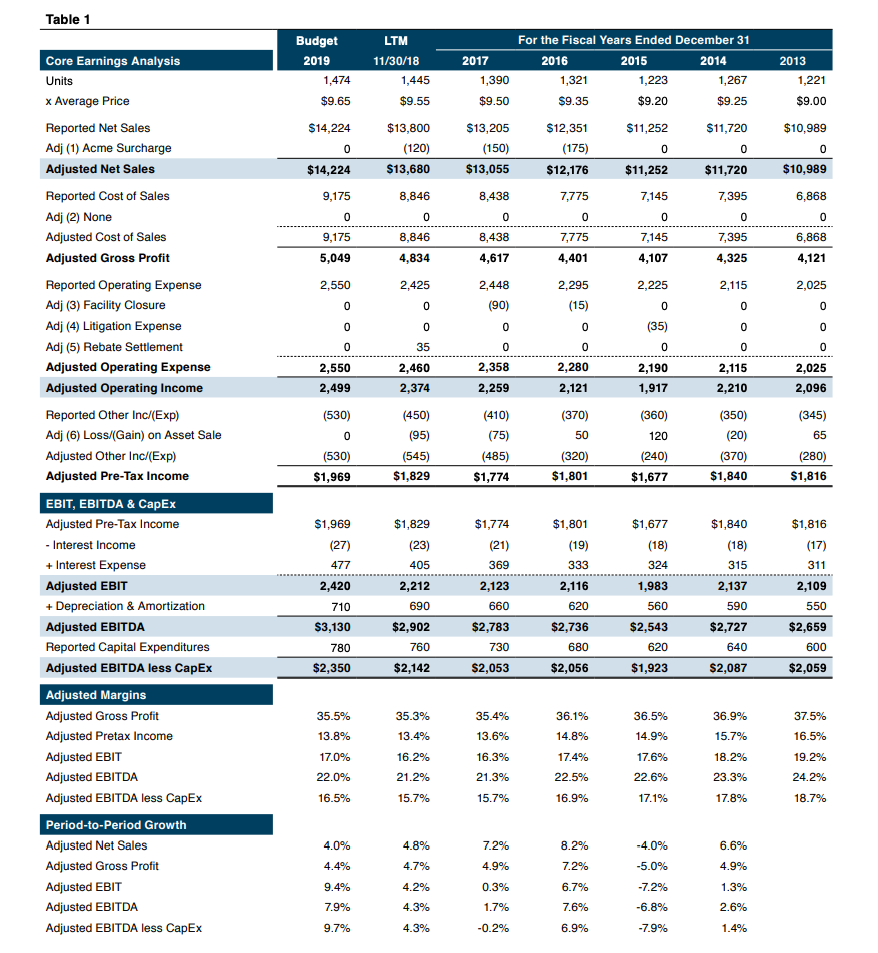

Table 1 below provides a sample overview of the template we use at Mercer Capital. The process is not intended to create an alternate reality; rather, it is designed to shed light on core trends about where the company has been and where it may be headed.

Adjustments

Adjustments typically consist of items that are non-recurring, unusual, and infrequent. They also may entail elements for a change in business operations, such as the addition of a new product or the discontinuation of a division. This is where judgment is particularly important because we have noticed a trend among some investors to credit businesses with future earnings for initiatives such as stepped-up hiring of revenue producers in which a favorable outcome is highly uncertain.

Minority vs. Control

Adjustments considered should take into account whether the valuation is on a minority interest or controlling interest basis. An adjustment for an unusual litigation expense will not be impacted by the level-of-value; however, other potential adjustments—particularly synergies a buyer could reasonably be expected to realize would only apply in a control valuation.

Core Trends vs. Peers

The development of the adjusted earnings analysis should allow one to identify the source of revenue growth and the trend in margins through a business cycle. The process also will facilitate comparisons with peers both historically and currently to thereby make further qualitative judgments about how the business is performing.

Out Year Budget vs. Adjusted History

The adjusted earnings history should create a bridge to next year’s budget, and the budget a bridge to multi-year projections. The basic question should be addressed: Does the historical trend in adjusted earnings lead one to conclude that the budget and multi-year projections are reasonable with the underlying premise that the adjustments applied are reasonable?

Core Earnings vs. Ongoing Earning Power

Core earnings differ from earning power. Core earnings represent earnings after adjustments are made for non-recurring items and the like in a particular year. Earning power represents a base earning measure that is representative through the firm’s (or industry’s) business cycle and, therefore, requires examination of adjusted earnings ideally over an entire business cycle. If the company has grown such that adjusted earnings several years ago are less relevant, then earning power can be derived from the product of a representative revenue measure such as the latest 12 months or even the budget and an average EBITDA margin over the business cycle.

Platform Companies/Roll-Ups

Companies that are executing a roll-up strategy can be particularly nettlesome from a valuation perspective because there typically is a string of acquisitions that require multiple adjustments for transaction related expenses and the expected earnings contribution of the targets. The math of adding and subtracting is straightforward, but what is usually lacking is seasoning in which a several year period without acquisitions can be observed in order to discern if past acquisitions have been accretive to earnings. Public market investors struggle with this phenomenon, too, but often the high growth profile of roll-ups will trump questions about earning power and what is an appropriate multiple until growth slows.

Income and Market-Based Valuation Approaches

In addition to providing insight into how a business is performing, the adjusted earnings statement will “feed” multiple valuation methods. These include the Discounted Cash Flow and Single Period Earning Power Capitalization Methods that fall under the Income Approach, and the Guideline (Public) Company and Guideline (M&A) Transaction Methods that constitute Market Approaches.

It may be obvious, but we believe an analysis of adjusted (and reported) earnings statements for a subject company over a multi-year period is a critical, if not the critical element, in valuing securities that are held in private equity and credit portfolios. Mercer Capital has nearly 40 years of experience in which tens of thousands of adjusted earnings statements have been created. Please call if we can help you value investments held in your portfolio.

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Portfolio Valuation Newsletter.

Value Drivers of a Store Valuation

Auto dealers, like most business owners, are constantly wondering about the value of their business. It’s easy to see how this issue moves to the forefront around certain events such as a transaction, buy-sell agreement, litigation, divorce, wealth-transfer event, etc. As our previous article “Six Different Ways to Look at a Dealership” points out, there are many other instances when a dealer can evaluate the condition, progress, or value of their store. Dealers can actually influence the value of their store prior to these obvious events by understanding the value drivers of a store valuation and addressing them on a consistent basis. So what are some of the value drivers of a store valuation?

Franchise

A store’s particular franchise affiliation has a major impact on value. Each franchise has a different reputation, selling strategy, target consumer demographic, etc. Public and value perception of franchises can be unique and are most easily illustrated through blue sky multiples. As the Haig Report and Kerrigan’s Blue Sky Report indicate, these blue sky multiples can vary over time and from period to period. Often stores and franchises are grouped into broader categories, such as: luxury franchises, mid-line franchises, domestic franchises, import franchises and/or high line franchises.

Real Estate/Quality of Facilities

Typically, most store locations and dealership operations are held in one entity, and the underlying real estate is held by a separate, often related, entity. Several issues with the real estate can affect a store valuation. First, an analysis of the rental rate and terms should be performed to establish a fair market value rental rate. Since the real estate is often owned by a related entity, the rent may be set higher or lower than market for tax or other motivations that would not reflect fair market value. Second, the quality and condition of the facilities are crucial to evaluate. Most manufacturers require facility and signage upgrades on a regular basis, often offering incentives to help mitigate these costs. It’s important to assess whether the store has regularly complied with these enhancements and is current with the condition of their facilities.

Employees/Management

The quality and depth of management can have a positive impact on a store valuation. Stores with greater management depth and less dependence on several key individuals will generally be viewed as less risky by an outside buyer. Also, a store’s CSI (Customer Service Index) and SSI (Service Satisfaction Index) rating can also influence incentives from the franchise and the overall perception of the consumer. A strong CSI and SSI are also a reflection of a strong service department and a commitment to quality customer service.

Recent Economic Performance

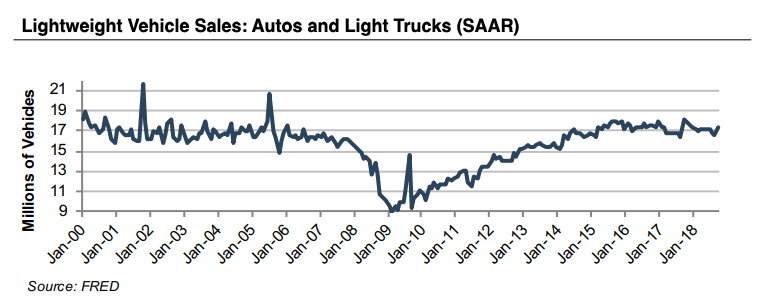

Like most industries, the auto industry is dependent on the national economy. We report later on the current SAAR (Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate) which is an indicator of economic performance and future sales in the auto industry. Current conditions of rising interest rates and a leveling out of the SAAR compared to October 2017 could be predictors of stabilizing values and less activity in the M&A market in the months to come. In addition to monitoring and understanding the current month’s SAAR, the longer-term history of the SAAR and its trends also provide insight into the auto industry and a store valuation. Below is a long-term graph of the SAAR from 2000 to 2017.

This visual evidence demonstrates the cyclicality of the auto industry. Unlike some industries that may be seasonal or cyclical in a given year, the auto industry tends to be cyclical over a longer period of several years. For instance, it’s common for a store to have stronger volumes and profitability for a period of 4-5 years, before experiencing a sluggish year or two. Store valuations should consider the cyclicality of the industry and not overvalue a store during a strong year, or undervalue it during a sluggish year.

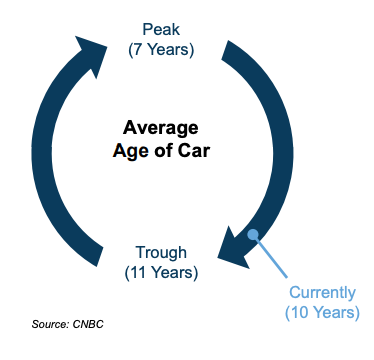

Another indicator of economic performance is an analysis of the auto cycle and where we are in that cycle based upon the average age of cars owned. The figure below illustrates the peak and trough of the auto cycle and where we sit today.

A store’s value and performance can be greatly influenced by the local economy as well as the national economy–sometimes more so. Certain markets are dominated by local economies of a certain trade or industry. Examples can be store locations near oil & gas refining areas, mining areas, or military bases. Each is probably more dependent on local economy conditions than national economy conditions.

Buyer Demand

Buyer demand in the transaction market can illustrate the value climate for store valuations. Typically, buyer demand is measured by the deal activity in the M&A market. The Haig Report indicated that the second quarter of 2018 transaction activity increased by 87% compared to second quarter of 2017. Further, the activity for the first six months of 2018 increased by 23% over the same six months of 2017. Similarly, Kerrigan’s figures reflect an increase in M&A activity of 13% in the first six months of 2018 compared to their data for the first six months of 2017.

Location/Market

The value of a store location can be more complex than urban vs. rural or major metropolitan city vs. minor metropolitan city. Each store location is assigned a certain area or group of zip codes referred to as an “area of responsibility” or “AoR”. Particularly, how does a location’s demographic characteristics line up with a certain franchise? For example, a high line store would perform better and seemingly be more valuable in a major metropolitan area with a high median income level, such as Beverly Hills or South Beach in Miami than in a mid western city. Conversely, mid-line stores would probably fare better in areas with more moderate median income levels.

Single-Point vs. Over-Franchised Market

The amount of competition in a store’s AoR, as well as the nearest location of a similar franchised store can also have an impact. It’s important to make the distinction that we are talking about a market and not a single-point store. A single-point market refers to a market where there is only one store of a particular franchise. An over-franchised market would be a larger market that may contain several stores of a particular franchise within a certain radius. Often, a store in a single-point market would be viewed as more valuable than one in an over-franchised market that would be competing with its own franchise for the same consumers. Additionally, the stores of the same franchise in the same market could be drastically different in size. One may be part of a larger auto group of stores, while the other may be a single-point dealership location, meaning its owner only owns that one location.

Conclusions/Observations

As we’ve discussed, the value of a store can be influenced by a variety of factors. Some of the factors are internal and can be affected by the owner, and some are external and are out of the control of the owner. To find out the value of your store, contact one of the automotive industry professionals at Mercer Capital.

Originally published in the Value Focus: Auto Dealer Industry Newsletter, Mid-Year 2018.

Six Different Ways to Look at a Dealership

Along the road to building the value of a dealership, it is necessary and appropriate to examine the dealership in a variety of ways. Each provides unique perspective and insight into how a dealer is proceeding along the path to grow the value of the dealership and if/when it may be ready to sell. Most dealers realize the obvious events that may require a formal valuation: potential sale/acquisition, shareholder dispute, death of a shareholder, gift/estate tax transfer of ownership, etc. A formal business valuation can also be very useful to a dealer when examining internal operations.

So, how does a dealer evaluate their dealership? And how can advisers or formal business valuations assist dealers examining their dealership? There are at least six ways and they are important, regardless of the size. All six of these should be contemplated within a formal business valuation.

- At a Point in Time. The balance sheet and the current period (month or quarter) provide one reference point. If that is the only reference point, however, one never has any real perspective on what is happening to the dealership.

- Relative to Itself Over Time. Dealerships exhibit trends in performance that can only be discerned and understood if examined over a period of time, often years.

- Relative to Peer Group. Many dealers participate in 20 groups. Among other things, the 20 groups can provide statistics that offer a basis for comparing performance relative to other dealerships.

- Relative to Budget or Plan. Every dealer of any size should have a budget for the current year. The act of creating a budget forces management to make commitments about expected performance in light of a company’s position at the beginning of a year and its outlook in the context of its local economy, industry and/or the national economy. Setting a budget creates a commitment to achieve, which is critical to achievement. Most financial performance packages compare actual to budget for the current year.

- Relative to Your Unique Potential. Every dealer has prospects for “potential performance” if things go right and if management performs. If a dealership has grown at 5% per year in sales and earnings for the last five years, that sounds good on its face. But what if similar locations have been growing at 10% during that period?

- Relative to Requirements by Franchise. Increasingly, dealerships are subject to requirements by the franchise including facility enhancements, working capital levels, CSI and SSI ratings, sales volumes, profitability, etc.

Why is it important to evaluate a dealership in these ways? Together, these six ways provide a unique way for dealers and key managers to continuously reassess and adjust their performance to achieve optimal results. A formal business valuation can communicate the dealership’s current position in many of these areas. Successive, frequent business valuations allow dealers and key managers the opportunity to measure and track the performance and value of the dealership or over time against stated goals and objectives.

Originally published in the Value Focus: Auto Dealer Industry Newsletter, Mid-Year 2018.

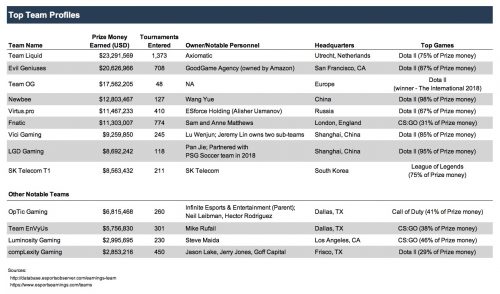

Valuing an eSports Team

The value of a company is generally dependent on three factors: risk, growth, and cash flow. Esports teams have an abundance of risk as well as growth potential. Considering eSports is a relatively new industry, the growth potential is huge. At the same time, and for the same reason, there is significant risk in the industry – it is too early to know if there is a proven, sustainable, cash flow generating business model.

Risk

Sustainability is one of the key risk factors for eSports teams. Viewer interest in games changes rapidly as new games are released. For the week of September 4, 2017, PLAYERUNKNOWNS’S BATTLEGROUNDS (“PUBG”) was the most viewed game with 112,741 average Twitch viewers. League of Legends (94,940) and Hearthstone (58,427) completed the top three. One year later, for the week of September 3, 2018, Fortnite led the way with 163,303 viewers while Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (129,580), and League of Legends (109,210) completed the top three. Hearthstone dropped to 36,849 average Twitch viewers for the week and PUBG dropped to 33,877 average Twitch viewers. Tracking viewership trends and competing in games that are popular is an important skill for teams that want to maintain relevance. Team Liquid’s CEO, Steve Arhancet, indicated the team looks for multiplayer games that have a thriving competitive community and are enjoyable to watch and play. Game publishers are another source of risk for eSports teams. The soon to be started Overwatch League (“OWL”) has a total buy-in price of $20 million split among its 20 teams. The high up-front cost to participate in the league has made some teams avoid the league.

Esports teams also have risks related to their players. Since eSports is not yet an established industry, there is not a set protocol for player contracts that allows teams to keep players for a long period of time. In addition, eSports teams must consider team dynamics when assembling a roster much like other professional team sports such as basketball, football, or hockey. If an eSports team does not have chemistry, it is unlikely they will perform at a high level. Frisco, Texas based eSports team CompLexity cited roster instability as a reason they dropped their Overwatch team.

Growth

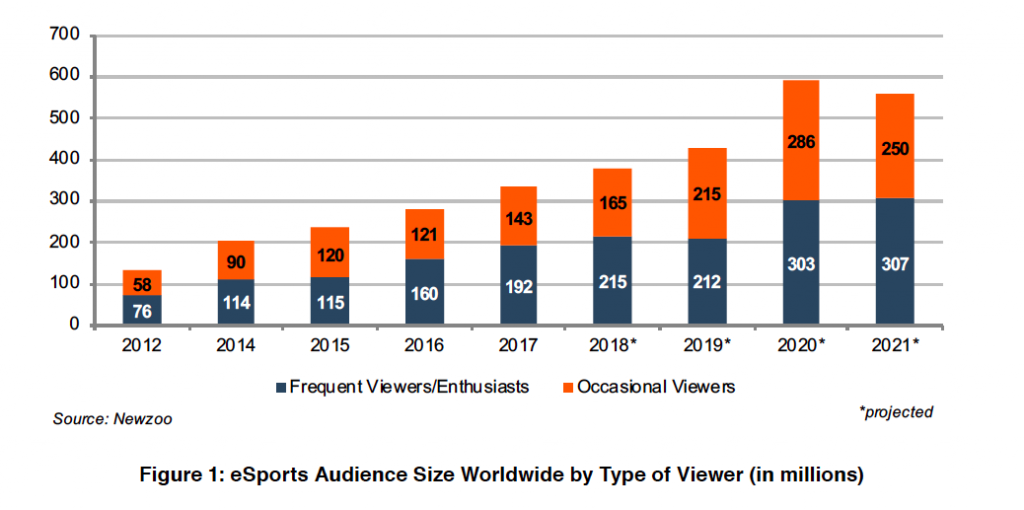

As shown in the chart below, the industry has been growing rapidly over recent years.

Esports industry research firm NewZoo projects 380 million total viewers in 2018, with 57% of those classified as frequent viewers/enthusiasts and 43% classified as occasional viewers. The compound annual growth rate of total viewers is projected to be 13.55% from 2017 to 2021.

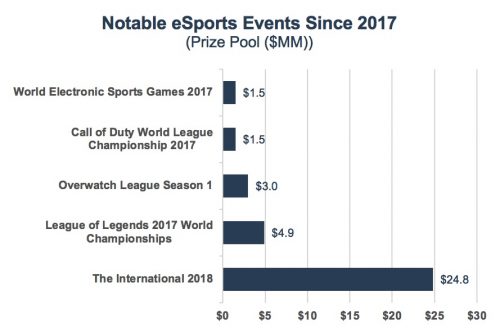

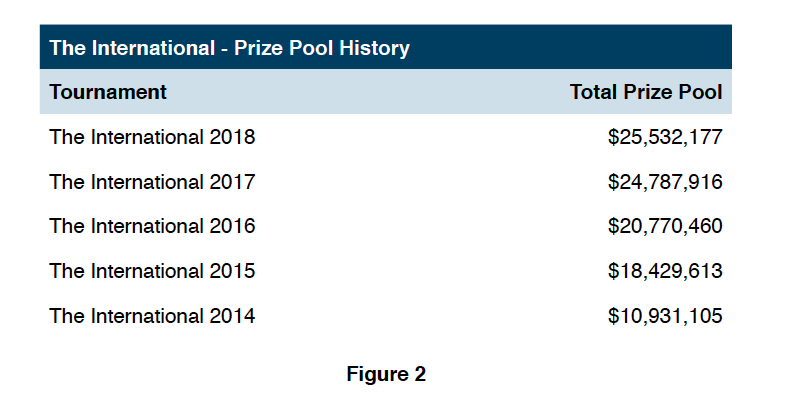

Another area where growth can be observed is the prize pool for major eSports tournaments. For example, The International 8, held in 2018 set a record for the largest single tournament prize pool in eSports history for the fifth consecutive year at $25.5 million. Prior iterations of The International had prize pools as shown in Figure 2. The compound annual growth rate of the prize pool from 2014 to 2018 was 24%.

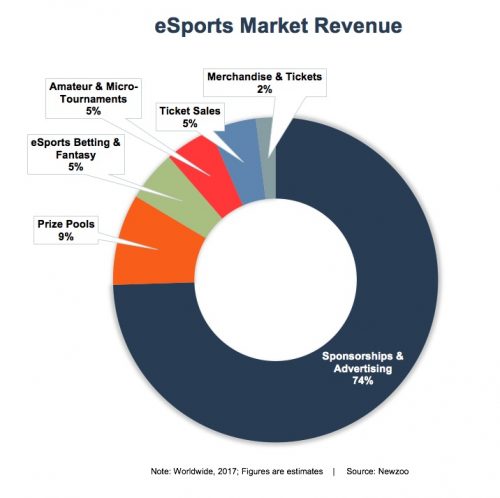

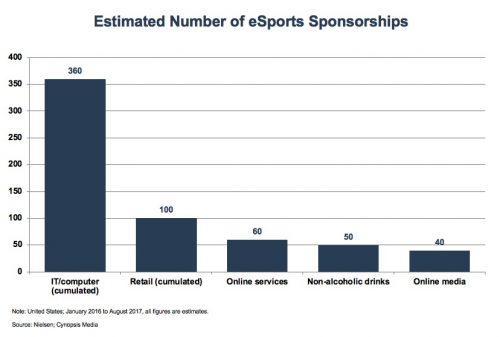

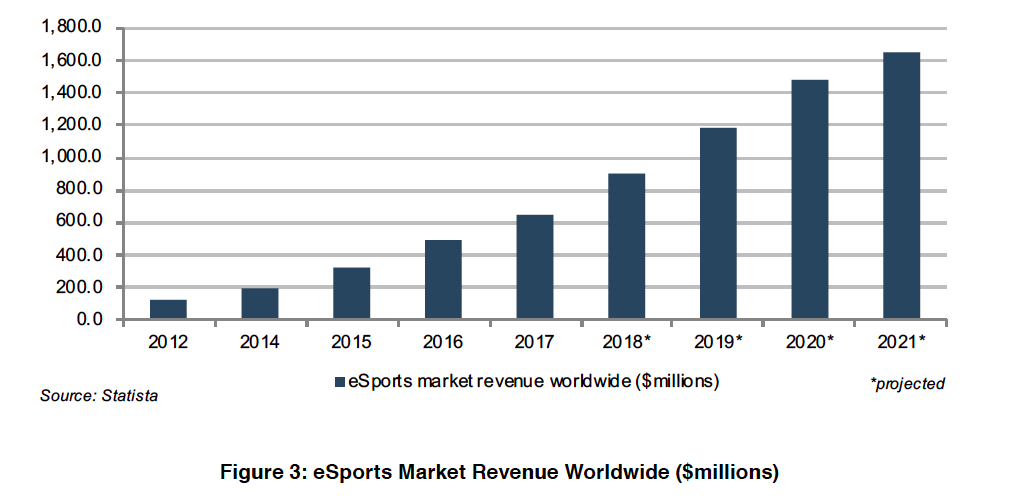

Newzoo defines industry revenue as the amount generated through the sale of sponsorships, media rights, advertising, publisher fees, tickets, and merchandising. Global eSports revenues are projected to reach $906 million in 2018. North America is projected to account for approximately 38% ($345 million) of global eSports revenue in 2018. As shown in Figure 3, global revenue for eSports is projected to reach $1.65 billion in 2021.

Cash Flow

Mercer Capital’s “eSports Business Models” shows how eSports teams make money and the costs of revenue associated with those income streams. Generally speaking, eSports teams have the following sources of revenue: sponsorships, broadcast revenue, merchandise sales, prize money, and naming rights. Costs of revenue include: player salaries, administrative personnel salaries, player housing expenses, training facility rent or operating expense, travel costs, and equipment/accessory expense. In broad terms, cash flow is calculated by subtracting operating expenses from total revenue.

Revenue can have different tiers of riskiness. For example, recurring revenue from sponsorships and subscriptions is less risky than merchandise sales or prize money. All else equal, teams with a higher ratio of recurring revenue to non-recurring revenue are considered less risky than a team with more non-recurring revenue than recurring revenue. Teams with lower risk cash flow are considered more valuable than teams with riskier cash flow.

Valuing an eSports Team

There are three approaches to value that are used or considered in any valuation. The three approaches to value are the cost approach, the income approach, and the market approach. This section walks through how an eSports team would be valued using each approach. Usually, valuation firms weight indications from each approach to arrive at a final conclusion of value.

Cost Approach

The cost approach is applied by adjusting the subject entity’s assets and liabilities to market value. Liabilities are then subtracted from assets to arrive at net asset value. A typical eSports team would have mostly intangible assets such as players. Tangible assets would be training facilities or team headquarters owned by the team. The cost approach, in many instances, would be weighted lightly, if at all, because it does not fully account for intangible assets.

Income Approach

The income approach is applied by calculating the cash flow either for a single period or for a projected multi-year period. At this stage, multi-year projections that account for potential growth will be the most common method employed. Capitalization at this point would be less likely to be used as growth has not stabilized within the industry. The risk and growth factors that would be considered for an eSports team will be the lynchpin to reasonably and properly measuring value. For an operating eSports team, the income approach would most likely be the heaviest weighted indication in a conclusion of value.

Market Approach

The market approach is similar to the income approach in that some element of cash flow is capitalized by some factor. However, in the market approach the capitalization factor is estimated using multiples indicated by public companies or transactions of private companies in the same or similar lines of business as the subject company. The market approach could be difficult to apply to an eSports team because, even though teams operate in the same general industry of eSports, there are many unique factors to each team. Within the market approach, cash flow, the capitalization factor(s)/multiple(s), or both may be adjusted based on how the subject team compares to the teams selected in the market approach. As the industry matures and more transactions occur, the market approach will develop alongside the industry.

Conclusion

In summary, eSports teams are valued using three methods: the cost approach, the market approach, and the income approach. Each of the methods considers three primary factors: risk, growth, and cash flow. Each eSports team is unique and there is no single formulaic way to value a team. However, in general, eSports teams will likely be valued using their historical and projected cash flows in the income approach. As the industry develops and matures there will be more transactions within the industry which will allow the market approach to become a more widely used tool.

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Valuing an eSports Team whitepaper.

Control Issues in ESOP Purchase Transactions

Tim R. Lee, ASA delivered the presentation, “Control Issues in ESOP Purchase Transactions” at the 2018 Las Vegas ESOP Conference and Trade Show hosted by The ESOP Association (November 8-9, 2018).

A description of Tim’s session can be found below:

Many ESOP purchase transactions are made on a controlling interest valuation basis. However, as has been highlighted in DOL investigations and ESOP litigation, whether an ESOP has “control” is not always a crystal clear issue. In addition, the Appraisal Foundation has recently published its MPAP paper which addresses specific factors to consider, including but not limited to the company’s cash flows, when valuing a company on a controlling interest basis. This advanced session will explore several issues around the topic of control, including what “paying for control” really means, appropriate post transaction corporate governance and how control rights are reflected in an ESOP appraisal.

Noncompete Agreements for Section 280G Compliance for Banks

Golden parachute payments have long been a controversial topic. These payments, typically occurring when a public company undergoes a change-in-control, can in some cases draw the ire of political activists and shareholder advisory groups. Golden parachute payments can also lead to significant tax consequences for both the company and the individual. Strategies to mitigate these tax risks include careful design of compensation agreements and consideration of noncompete agreements to reduce the likelihood of additional excise taxes.

When planning for and structuring an acquisition, companies and their advisors should be aware of potential tax consequences associated with the golden parachute rules of Sections 280G and 4999 of the Internal Revenue Code. A change-in-control (CIC) can trigger the application of IRC Section 280G, which applies specifically to executive compensation agreements. Proper tax planning can help companies comply with Section 280G and avoid significant tax penalties.

Golden parachute payments usually consist of items like cash severance payments, accelerated equity-based compensation, pension benefits, special bonuses, or other types of payments made in the nature of compensation. In a CIC, these payments are often made to the CEO and other named executive officers (NEOs) based on agreements negotiated and structured well before the transaction event. In a single-trigger structure, only a CIC is required to activate the award and trigger accelerated vesting on equity-based compensation. In this case, the executive’s employment need not be terminated for a payment to be made. In a double-trigger structure, both a CIC and termination of the executive’s employment are necessary to trigger a payout.

Adverse tax consequences may apply if the total amount of parachute payments to an individual exceeds three times (3x) that individual’s “Base Amount”. The Base Amount is generally calculated as the individual’s average annual W-2 compensation over the preceding five years.

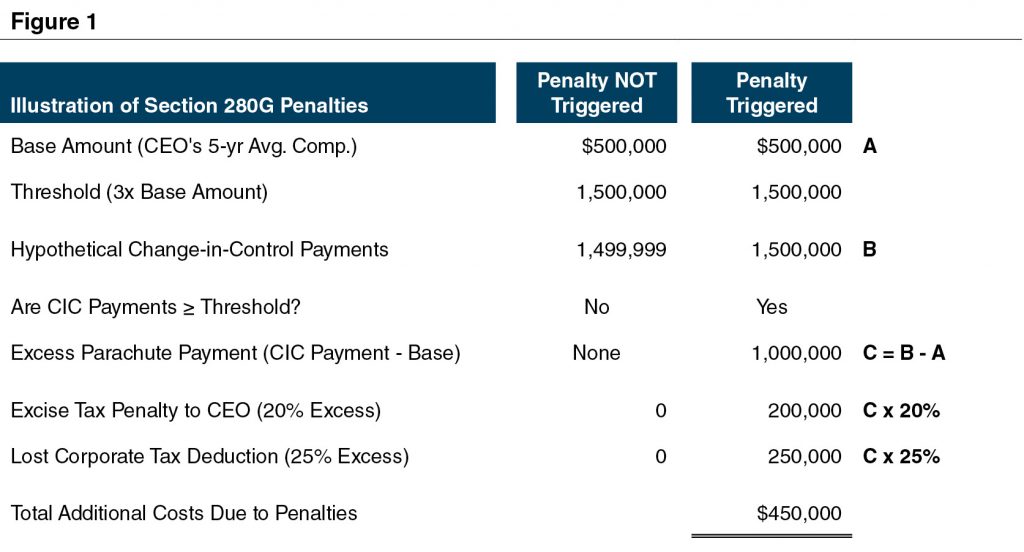

As shown in Figure 1, if the (3x) threshold is met or crossed, the excess of the CIC Payments over the Base Amount is referred to as the Excess Parachute Payment. The individual is then liable for a 20% excise tax on the Excess Parachute Payment, and the employer loses the ability to deduct the Excess Parachute Payment for federal income tax purposes.

Several options exist to help mitigate the impact of the Section 280G penalties. One option is to design (or revise) executive compensation agreements to include “best after-tax” provisions, in which the CIC payments are reduced to just below the threshold only if the executive is better off on an after-tax basis. Another strategy that can lessen or mitigate the impact of golden parachute taxes is to consider the value of noncompete provisions that relate to services rendered after a CIC. If the amount paid to an executive for abiding by certain noncompete covenants is determined to be reasonable, then the amount paid in exchange for these services can reduce the total parachute payment.

According to Section 1.280G-1 of the Code, the parachute payment “does not include any payment (or portion thereof) which the taxpayer establishes by clear and convincing evidence is reasonable compensation for personal services to be rendered by the disqualified individual on or after the date of the change in ownership or control.” Further, the Code goes on to state that “the performance of services includes holding oneself out as available to perform services and refraining from performing services (such as under a covenant not to compete or similar arrangement).”

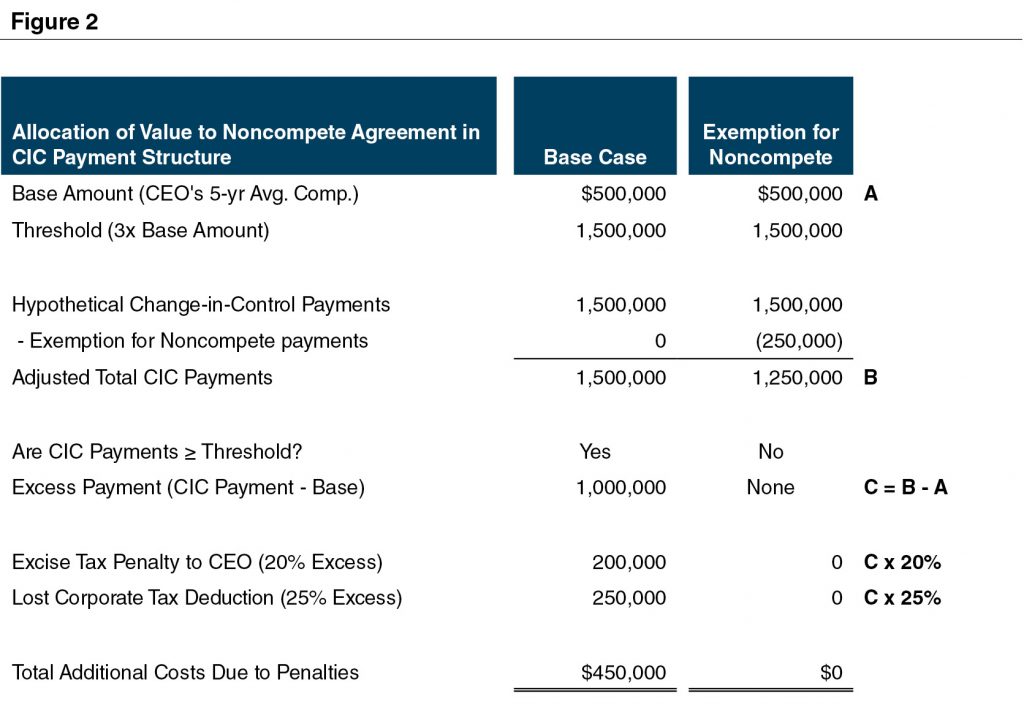

Figure 2 illustrates the impact of a noncompete agreement exemption on the calculation of Section 280G excise taxes.

How can the value of a noncompete agreement be reasonably and defensibly calculated? Revenue Ruling 77-403 states the following:

“In determining whether the covenant [not to compete] has any demonstrable value, the facts and circumstances in the particular case must be considered. The relevant factors include: (1) whether in the absence of the covenant the covenantor would desire to compete with the covenantee; (2) the ability of the covenantor to compete effectively with the covenantee in the activity in question; and (3) the feasibility, in view of the activity and market in question, of effective competition by the covenantor within the time and area specified in the covenant.”

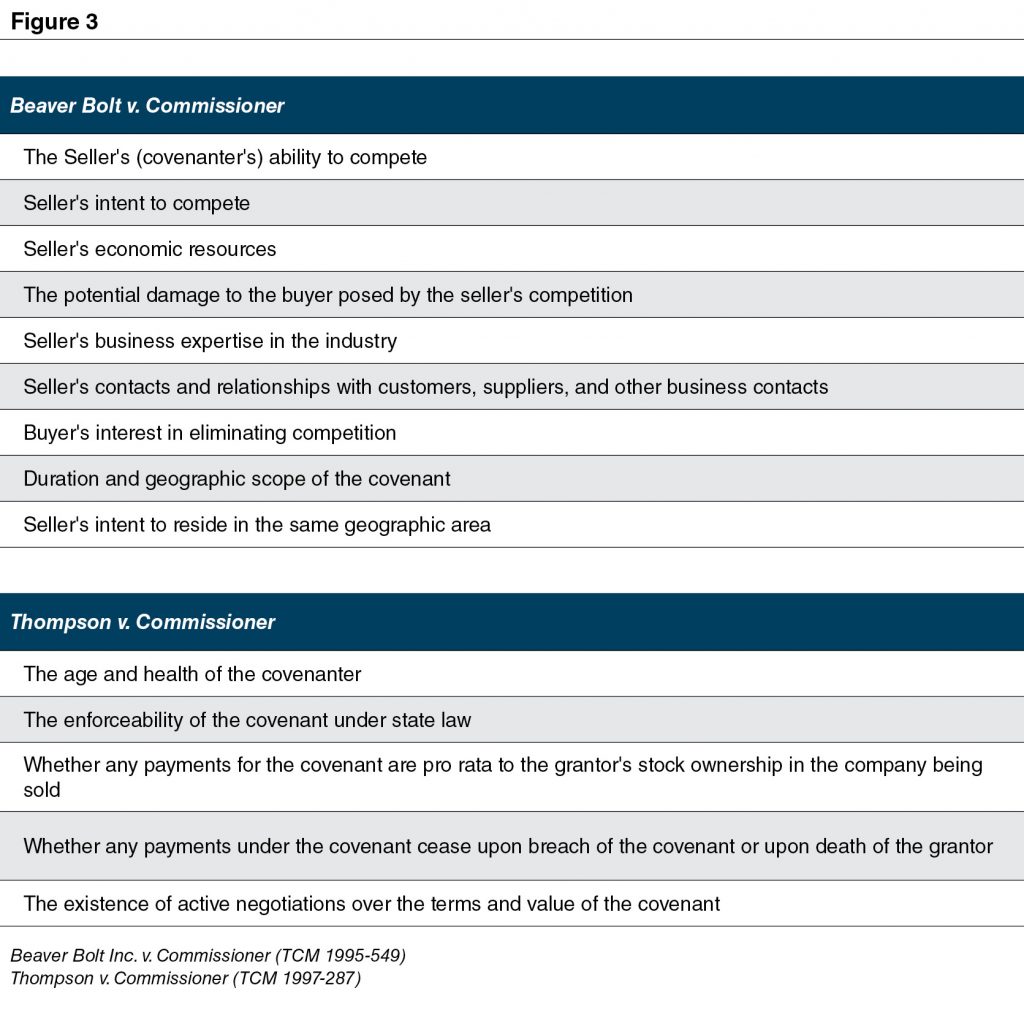

Some of the factors to be considered when evaluating the “economic reality” of a noncompete agreement have been enumerated in various Tax Court cases, as detailed in Figure 3.

A common method to value noncompete agreements is the “with or without” method. Fundamentally, a noncompete agreement is only as valuable as the stream of cash flows the firm projects “with” an agreement compared to “without” one. The difference between the two projections effectively represents the “cost” of competition, or stated differently, the value of the cash flows protected by the noncompete agreement. Cash flow models can be used to assess the impact of competition on the firm based on the desire, ability, and feasibility of the executive to compete. Valuation professionals consider factors such as revenue reductions, increases in expenses, and the impact of employee solicitation and recruitment.

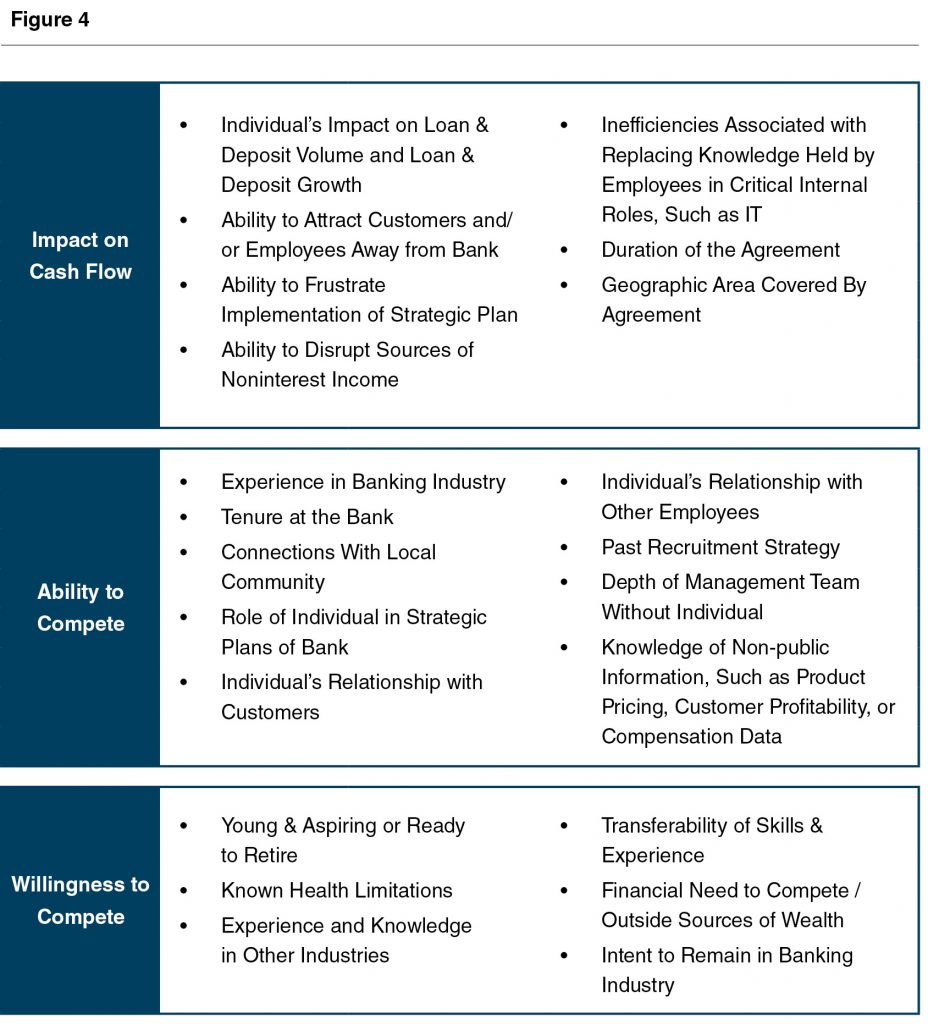

To illustrate how the three factors of Revenue Ruling 77-403 can be evaluated in light of the specific terms of a noncompete agreement for a bank employee, we put together Figure 4.

Mercer Capital provides independent valuation opinions to assist companies with IRC Section 280G compliance. Our opinions are well-reasoned and well-documented regarding the factors influencing the value of non-compete agreements.

6 Ways to Look at a Business

Along the road to building the value of a business it is necessary, and indeed, appropriate, to examine the business in a variety of ways. Each provides unique perspective and insight into how a business owner is proceeding along the path to grow the value of the business and if/when it may be ready to sell. Most business owners realize the obvious events that may require a formal valuation: potential sale/acquisition, shareholder dispute, death of a shareholder, gift/estate tax transfer of ownership, etc. A formal business valuation can also be very useful to a business owner when examining internal operations.

So, how does a business owner evaluate their business? And how can advisers or formal business valuations assist owners examining their businesses? There are at least six ways and they are important, regardless of the size of the business. All six of these should be contemplated within a formal business valuation.

- At a Point in Time. The balance sheet and the current period (month or quarter) provide one reference point. If that is the only reference point, however, one never has any real perspective on what is happening to the business.

- Relative to Itself over Time. Businesses exhibit trends in performance that can only be discerned and understood if examined over a period of time, often years.

- Relative to Peer Groups. Many industries have associations or consulting groups that publish industry statistics. These statistics provide a basis for comparing performance relative to companies like the subject company.

- Relative to Budget or Plan. Every company of any size should have a budget for the current year. The act of creating a budget forces management to make commitments about expected performance in light of a company’s position at the beginning of a year and its outlook in the context of its local economy, industry and/or the national economy. Setting a budget creates a commitment to achieve, which is critical to achievement. Most financial performance packages compare actual to budget for the current year.

- Relative to your Unique Potential. Every company has prospects for “potential performance” if things go right and if management performs. If a company has grown at 5% per year in sales and earnings for the last five years, that sounds good on its face. But what if the industry niche has been growing at 10% during that period?

- Relative to Regulatory Expectations or Requirements. Increasingly, companies in many industries are subject to regulations that impact the way business can be done or its profitability.

Why is it important to evaluate a company in these ways? Together, these six ways of examining a company provide a unique way for business owners and key managers to continuously reassess and adjust their performance to achieve optimal results.

A formal business valuation can communicate the company’s current position in many of these areas. Successive, frequent business valuations allow business owners and key managers the opportunity to measure and track the performance and value of the company over time against stated goals and objectives.

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Tennessee Family Law Newsletter, Third Quarter 2018

How to Determine Whether an Asset and Its Appreciation is Marital or Separate Property

Under Tennessee law, marital property is subject to property division and separate property is excluded from property division in a divorce. The underlying factor in this distinction is whether the increase in value between the date of marriage and the date of divorce resulted from efforts by a spouse, known as active appreciation, or from external (economic, market, industry) forces, known as passive appreciation. While these concepts seem simple, the classifications are only part of the story.

Classification of Marital and Separate Property

Tennessee Code 36-4-121 defines marital property as “all real and personal property, both tangible and intangible, acquired by either or both spouses during the course of the marriage up to the date of the final divorce hearing.”

The same code section defines separate property as “all real and personal property owned by a spouse before marriage, property acquired in exchange for property acquired prior to marriage, property acquired by a spouse at any time by gift, bequest, devise or descent, etc.”

Can a Marital Asset Ever Become Separate or Can a Separate Asset Ever Become Martial?

Let’s examine this question in the context of a business or business interest as an example. If a couple or spouse starts a business or acquires a business interest during the marriage, then it would be classified as marital. Any appreciation or increase in value of the business or business interest would also be classified and remain a marital asset.

Conversely, if a spouse starts a business or business interest prior to the date of marriage or acquires it by gift, bequest, devise or descent, then initially that business or business interest would be classified as a separate asset. What happens to that business or business interest if the value changes during the marriage? The increased value or appreciation of a business or business interest could be classified as marital or separate. How is this possible?

If both spouses contribute to the preservation and appreciation of a separate property business or business interest and the contribution is “real” and “significant,” then the appreciation (increase in value) of the business or business interest would be determined to be a marital asset and subject to division. This is known as active appreciation.

If, on the other hand, both spouses do not contribute to the appreciation in value, there is no appreciation in value, or the appreciation is attributable to passive forces, such as inflation, then the separate property business or business interest would remain separate.

The following steps assist the financial analyst during the process:

- Is the business, or business interests, marital or separate?

-

- a. Compare the formation or inheritance date(s) to date of marriage.

-

- If the answer to (1) concludes pre-marital, separate property, value the business as of the date of marriage as a starting point. Then, value the business as of the date of divorce (or as close to as possible).

- If the value has increased from the date of marriage to the date of divorce, a determination of active (marital) versus passive (separate) shall commence.

What Must Be Demonstrated

Tennessee code states that the substantial contribution of the non-business spouse “may include, but not be limited to, the direct or indirect contribution of the spouse as a homemaker, wage earner, parent or financial manager, together with such other factors as the court having jurisdiction thereof may determine.”

A non-business owner spouse must be able to demonstrate two things in order for appreciation of a separate property business or business interest to become a marital asset: substantial contribution of both spouses contributing to the appreciation,and actual appreciation in the value of the business or business interest during the marriage. Most often, a valuation of the business or business interest at the date of marriage and also the date of filing would be required among other things to try and support this claim.

This article has used a business or business interest to illustrate the concepts of martial vs. separate assets and also the appreciation in value. It should be noted that there could be potentially other considerations for these same issues with other assets, such as investment properties or passive assets (401Ks, etc.).

Conclusion

A financial expert, specifically one with expertise in business valuation, is vital in the determination of active appreciation (separate) versus passive appreciation (marital).

The professionals of Mercer Capital can assist in the process. For more information or discuss an engagement in confidence, please contact us.

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Tennessee Family Law Newsletter, Third Quarter 2018

Pro Sports Player Contract Valuations And The New Tax Law

Download Article

The change in the tax law brings additional attention to player contract values as they are now potentially taxable events for teams.

As the 2018 calendar year moves towards a close, front offices and league offices across professional sports are at different places:

- MLB just finished their year, and teams are taking stock of what happened and planning for winter meetings.

- MLS is a few weeks away from the MLS Cup in early December.

- The NFL is just past the halfway point as the trade deadline recently past and the playoff race is being run.

- The NBA and NHL are getting their seasons off the ground and haven’t hit the quarter pole yet.

Players are at the heart of all these leagues. Whether a rookie, veteran, all-star, or benchwarmer, these players all have value. Now, as a result of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, exactly how much value is a very real question for many player contracts involved in a trade, adding complexity to an already complicated process.

Beginning in 2018, the tax treatment for certain player-for-player trades changed. Player-for-player trades have been treated as a like-kind exchange for decades. However, the appreciation in value of a traded player’s contract has now potentially become a taxable event for teams. Considering this, when a taxable event occurs, teams must measure this appreciation in terms of dollars in order to report potential capital gains to the IRS. This is where valuation issues become relevant.

Contract Valuations: The CFO’s Domain Is Now Merging With Team Operations

As important as they are to a sports team, historically player contracts rarely needed to be separately valued. When they did, it was typically when a franchise was bought or sold. In that situation, player contracts (along with other identified intangibles) were allocated as an asset in the purchase price.

Franchise transitions happen relatively infrequently; therefore, some front offices, tax advisors, and valuation firms don’t have experience in this area. Mercer Capital is one of very few with deep experience in this area.

Historically, general managers and personnel departments valued player contracts internally which produced a relative valuation result. This value result cannot now be directly used by the tax and finance department to report values. Therefore, it’s important to work with professionals who have experience determining the fair market value of player contracts and understand the complexities of each league.

Trades are usually made for (i) other players, (ii) draft pick rights, (iii) cash, or a combination of these. When analyzing the trade deal, only one scenario would appear to directly value player contracts – a cash deal. However, even this can be somewhat deceiving when it comes to fair market value as player development and other hidden costs may need to be included. Indeed, draft picks and draft positioning function as a currency in leagues, especially the NFL with larger rosters and shorter playing careers. Trades and player values are often discussed in terms of relative draft pick positioning.

Other factors can come into play as well. What if the teams involved in a trade had rationale for it not directly related to contract value, like salary cap issues? The fair market value of a contract could be only one of many issues at play in a trade under various scenarios.

Therefore, when determining a player contract’s fair market value, it’s important to have a valuation methodology that comports with a team’s internal rationale, as well as having IRS supportability.

Valuation Approaches And Considerations

Numerous factors impact the fair market value of a player contract, including:

- Historical performance

- Potential future performance

- Position played

- Commercial and media potential

- Off-field behavior

- Age Physical characteristics

- Roster and league attrition

- Draft position

- Team performance and constitution

- Length of existing contract

- Other

Valuation Approaches

There are three approaches to value that could potentially capture the above factors into a single dollar figure: income, market, and cost approaches. The income approach is rarely used because it is difficult to directly trace an individual player’s impact on the team’s income stream. The market approach and the cost approach, or a hybrid of the two, are more typically employed to value player contracts.

Valuation Considerations

Due to the nature of the asset, a mix of quantitative and qualitative analyses are used to develop a model to value player contracts and the economic benefit (or detriment) they possess relative to the rest of the team’s roster. This is done in comparison to alternatives that a team may have and a player may have under their collective bargaining agreement. Once adjustments are made, a value can be estimated. A hybrid method using both the market and cost approach has the following benefits:

- Data driven

- Consistent

- Tethered to the framework of a league’s collective bargaining agreement

- Can ascribe value to draft pick rights as well as player contracts

Of course, values are subject to facts and circumstances. Potential differences in opinions on either side of a trade is an issue that is likely to arise. If teams cannot agree to a value, or appraisals of the same player contract result in different values, there is the potential of an IRS audit situation for both teams on the same trade.

Conclusion

The change in the tax law brings additional attention to player contract values. It may or may not impact how a team approaches its business of winning championships, but it will impact how leagues and front offices approach valuations of player contracts. Will the leagues, taxpayers, and the IRS find common ground? Perhaps it will depend on how touchdowns, goals, hits, and rebounds translate into value on a tax return.

Valuation Tax Panel

This presentation was delivered by Z. Christopher Mercer, FASA, CFA, ABAR at the AICPA 2018 Forensic & Valuation Services Conference.

A short description of the presentation can be found below:

How substantial is tax reform’s effect on business valuation? There has been a lot of discussion and interest in the new TCJA especially, but how has this changed the way we think about valuation. The panel will discuss different views on tax reform related to valuation modeling, forecasting, and subjective assumptions used when considering the TCJA.

Learning objectives include:

- Understand the various implications of the TCJA on pass through entity valuations

- Explore the effect on public company and transaction multiples post TCJA

- Review best practices with model considerations in light of sunset provisions

- Learn the effect of bonus depreciation and interest expense limitations

Active Passive Appreciation – Current Update

This presentation, delivered by Z. Christopher Mercer, FASA, CFA, ABAR at the AICPA 2018 Forensic & Valuation Services Conference, covers when and why an active passive analysis is needed, how these analyses are typically done, and the importance of working with engaging counsel for jurisdictional nuances.

Learning objectives include:

- Understand the key elements involved in an active passive analysis

- Update of current practice and understand how active passive analyses are typically done around the country

- Discussion of jurisdictional nuances

Views from the Road: What Do Community Banks, FinTech, and Buffalo Have in Common?

In the last few weeks, I presented at two events geared towards helping community banks achieve better performance: the Moss Adams Community Banking Conference in Huntington Beach, California and the FI FinTech Unconference in Fredericksburg, Texas. The FI FinTech Unconference had a recurring visual theme of the buffalo, which struck me as an insightful image for a FinTech conference.

Much of the discussions at both conferences focused on the ability of community banks to adapt, survive, and thrive rather than thin out like the once massive North American buffalo herd. Both events had several presentations and discussions around FinTech and the need for community banks to evolve to meet customer expectations for improved digital interactions. Beyond thinking that I will miss the great views and weather I had for both trips, I came away with a few questions bankers should consider.

How Can Community Banks Compete with Larger Banks?

Larger banks are taking market share from smaller banks and have been gathering assets and deposits at a faster pace than community banks (defined as banks with less than $10 billion of assets) the last few decades. For example, banks with assets greater than $10 billion controlled around 85% of assets in mid-2018 compared to 50% in 1994. This is a significant trend illustrating how much market share community banks have ceded. Further, larger banks are producing higher ROEs, largely driven by higher levels of non-interest income (~0.90% of assets vs ~0.55%) and better operating leverage as measured by the efficiency ratio (~59% vs ~66%). The larger banks may widen their lead, too, given vast sums that are being spent on digital enhancements and other technology ventures to improve the client experience.

Can FinTech Serve as a Value Enhancer and Help Community Banks Close the Performance Gap with Larger Banks?

Most community banks are producing an ROE below 10%—an inadequate return for shareholders despite low credit costs. As a result, the critical role that a community bank fills as a lender to small business and agriculture is at risk if the board and/or shareholders decide to sell due to inadequate returns. Confronting this challenge requires the right team executing the right strategy to produce competitive returns for shareholders. FinTech solutions, rather than geographic expansion through branching and acquisitions, may be an option if FinTech products and processes can address areas where a bank falls short (e.g., wealth management).

Can Community Banks Hold Ground and Even Win the Fight for Retail Deposits?

Many community bank cost structures are wed to physical branches while customers— especially younger ones—are increasingly interacting with institutions first digitally and secondarily via a physical location. This transition is occurring at a time when core deposits are increasing in value to the industry as interest rates rise. In response, several larger banks, such as Citizens Financial, have increased their emphasis on digital delivery to drive incremental deposit growth. Additionally, as funding costs increase, some FinTech companies are being forced to consider partnerships with banks. Thus far, the digital banking push and the formal partnering of FinTech companies and banks are incremental in nature rather than reflective of a wholesale change in business models. Nonetheless, it will be interesting to see whether community banks can adapt and effectively use technology and FinTech partnerships to compete and win retail deposit relationships in a meaningful way.

How Can Community Banks Develop a FinTech Framework?

Against this backdrop, I see four primary steps to developing a FinTech framework:

- Identify attractive FinTech niches such as deposits, payments, digital lending, wealth management, insurance, or efficiency (i.e., tech initiatives designed to reduce costs)

- Identify attractive FinTech companies in those niches

- Develop a business case for different strategies (estimate the Internal Rates of Returns and IRRs)

- Compare the different strategies and execute the optimal strategy

What Are Some Immediate Steps that Banks Can Take Regarding FinTech?

The things that banks can do right now to explore FinTech opportunities are:

- Get educated. There are an increasing number of events for community bankers incorporating FinTech into their agenda and we have a number of resources on the topic as well

- Begin or continue to integrate FinTech into your strategic plan

- Determine what your customers want/need/expect in terms of digital offerings

- Seek out FinTech partners that provide solutions and begin due diligence discussions

How Mercer Capital Can Help

Mercer Capital can help your bank craft a comprehensive value creation strategy that properly aligns your business, financial, and investor strategies. Given the growing importance of FinTech solutions to the banking sector, a sound value creation strategy needs to incorporate FinTech.

We provide board/management retreats to educate you about the opportunities and challenges of FinTech for your institution. We can:

- Help your bank identify which FinTech niches may be most appropriate for your bank given your existing market opportunities

- Help your bank identify which FinTech companies may offer the greatest potential as partners for your bank

- Help provide assistance with valuations should your bank elect to consider investments or acquisitions of FinTech companies

We are happy to help. Contact us at 901.685.2120 to discuss your needs.

Originally published in Bank Watch, October 2018.

Intrinsic Value and Valuation Multiples

This presentation, originally delivered by Z. Christopher Mercer, FASA, CFA, ABAR at the Fairfax Bar Association’s Annual Conference in October 2018, discusses the intrinsic value standard of value in Virginia divorce-related valuations of closely held business assets. Additionally, this presentation also covers developing valuation multiples with credibility.

Accounting Standards Update 2016-01: Impairment Considerations for Equity Investments

ASU 2016-01 shook up financial reporting at the beginning of the year, as companies scrambled to determine compliance with the new requirements for reporting equity investments.

The rise of corporate venture capital over recent years largely flew under the accounting radar until this update took effect, creating significant volatility for many corporate investors in their reported earnings as they were required to recognize the gains and losses from investments previously held at cost.

Now that the initial shock has worn off, CFOs may be able to rest a little easier, but they shouldn’t forget about the requirements under ASU 2016-01 entirely.

Even if the company elected the measurement alternative that allows for the investment to be reported at cost, don’t forget about the requirement for impairment testing that goes along with it. Some companies may choose to perform the initial Step Zero analysis internally before engaging a valuation firm to navigate the rest of the process, while others turn over the entire process to a valuation professional.

“An entity may elect to measure an equity security without a readily determinable fair value [and that does not qualify for the practical expedient]…at its cost minus impairment, if any, plus or minus changes resulting from observable price changes in orderly transactions for the identical or a similar investment of the same issuer.”

ASU 2016-01 Paragraph 321-10-35-2

Originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Financial Reporting Update: Goodwill Impairment

Industry Considerations for Step Zero: Qualitative Assessments

What is Step Zero?

A qualitative approach to test goodwill for impairment was introduced by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (“FASB”) when it released Accounting Standards Update 2011-08 (“ASU 2011-08”) in September 2011 as an update to goodwill impairment testing standards under Topic 350, Intangibles—Goodwill and Other. ASU 2011-08 set forth guidance for an optional qualitative assessment to be performed before the traditional quantitative two step goodwill impairment testing process. This preliminary qualitative assessment is known as “Step Zero.” The goal of Step Zero is to simplify and reduce costs of performing the traditional quantitative goodwill impairment test process.

According to ASU 2011-08, Step Zero allows entities “the option to first assess qualitative factors to determine whether the existence of events or circumstances leads to a determination that it is more likely than not that the fair value of a reporting unit is less than its carrying amount.”

Step One is required only if the qualitative assessment supports the conclusion that it is more likely than not (i.e., likelihood greater than 50%) that the fair value is less than the carrying value. Otherwise, Step One of the goodwill impairment testing process is not required. Alternatively, Step Zero can be skipped altogether, and the traditional quantitative goodwill impairment test can be performed beginning with Step One.

Industry Considerations

The standards update release by FASB outlines the individual qualitative categories of the assessment. Specific qualitative events and circumstances to be evaluated include the economy, industry, cost factors, financial performance, firm-specific events, reporting unit events, and changes in share price.

ASU 2011-08 defines industry events and circumstances as follows:

“Industry and market conditions such as a deterioration in the environment in which an entity operates, an increased competitive environment, a decline in market-dependent multiples or metrics (consider in both absolute terms and relative to peers), a change in the market for an entity’s products or services, or a regulatory or political development.”

The process of evaluating an industry involves assessing each of these stated events and circumstances since the previous reporting period and determining how they affect the comparison of fair value to carrying value. By comparing current conditions to the prior period, an analysis of relative improvement or deterioration can be made concerning each industry factor and the industry as a whole.

Increasing multiples, share prices, financial metrics, and M&A activity indicate that an industry is improving and suggests that it is more likely than not that the reporting unit’s fair value is greater than its carrying value. Decreasing multiples, share prices, financial metrics, and M&A activity indicate the industry is weakening and suggests that fair value may be less than the reporting unit’s carrying value.

Industry Analysis

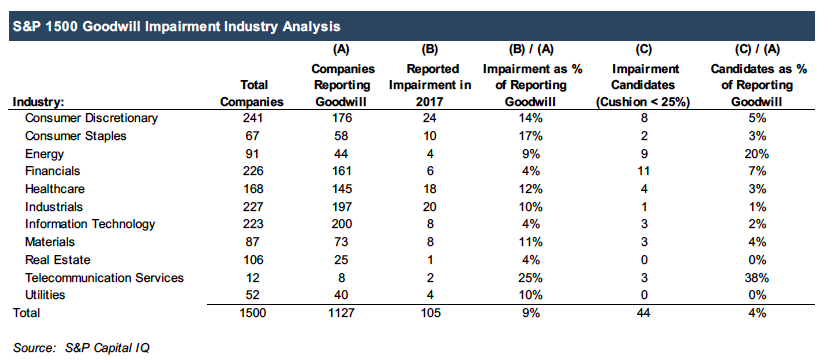

An analysis of the S&P 1500, an index that includes approximately 90% of the market capitalization of U.S. stocks, reveals the prevalence of impairment in different industries. For example, of the companies reporting goodwill on their balance sheets, 25% of telecommunication, 17% of consumer staples, and 14% of consumer discretionary companies recorded goodwill impairment charges in 2017.

On the other hand, the more robust performance of financial, information technology, and real estate companies is manifest in that only 4% of companies reporting goodwill in each industry recorded a goodwill impairment charge in 2017.

Further analysis indicates that companies in the energy and telecommunication industries are currently more likely to be potential impairment candidates as 20% and 38%, respectively, of companies reporting goodwill have cushions (the amount by which market value of equity exceeds book value of equity) of less than 25%. Deterioration in the operating environment of these industries may result in an increase in goodwill impairment charges. Industries with fewer impairment candidates at the moment include real estate, utilities, and industrials.

Industry considerations are particularly important to the qualitative assessment and provide valuable insight on the potential for impairment. The qualitative assessment is especially valuable in industries that are performing well as it is less likely that goodwill is impaired.

Step Zero provides the opportunity to perform a preliminary qualitative analysis to determine the necessity of performing the traditional two step goodwill impairment test and can lead to a simpler, more efficient impairment testing process.

The analysts at Mercer Capital have experience in, and follow, a diverse set of industries. We help clients assemble, evaluate, and document relevant evidence for the Step Zero impairment test. Call us today so we can help you.

Originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Financial Reporting Update: Goodwill Impairment

Tax Reform and Impairment Testing

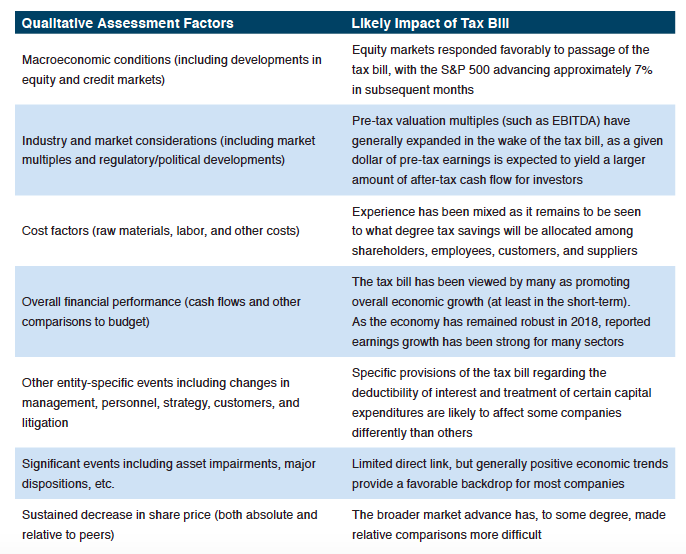

Earlier this year, we considered the impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (“TCJA”) on purchase price allocations. In this article, we turn our focus to the impact of the TCJA on goodwill impairment testing. Changes to the tax code will affect both the qualitative assessment (often referred to as Step Zero) and quantitative impairment test.

Qualitative Assessment

Companies preparing a qualitative assessment are required to assess “relevant events and circumstances” to evaluate whether it is more likely than not that goodwill is impaired. ASC 350 includes a list of eight such potential events and circumstances.

Quantitative Assessment

The same features which, on balance, have made it more likely that reporting units will garner a favorable qualitative assessment also contribute to the fair value of reporting units under the quantitative assessment.

- Reduction in income tax rate. All else equal, a reduction in the applicable federal income tax rate from 35% to 21% increases after-tax cash flows and contributes to higher fair values for reporting units.

- Bonus depreciation provisions. The tax bill allows certain capital expenditures to be deducted immediately for purposes of calculating taxable income. While the aggregate amount of depreciation deductions is unaffected, the acceleration of the timing of tax benefits can have a marginally positive effect on the fair value of some reporting units.

- Interest deduction limitations. One potentially negative effect of the tax bill on reporting unit fair values is the limitation on the amount of interest expense that is deductible for tax purposes. For some highly-leveraged businesses, the interest deduction limitation can increase the weighted

average cost of capital. We expect the interest deduction limitations to adversely affect only a small minority of companies. - Increase in after-tax cost of debt. When calculating the cost of debt as a component of the cost of capital, analysts multiply the pre-tax cost of debt by one minus the corporate tax rate. The new lower tax rate will, therefore, cause the after-tax cost of debt to increase by a small increment. All else equal, an increase to the weighted average cost of capital has a negative impact on the fair value of a reporting unit. On balance, we expect the negative effect from higher costs of capital to be smaller than the positive cash flow effect from lower tax rates.

Conclusion

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 is a material factor to be considered in both qualitative and quantitative assessments of goodwill impairment in 2018. While the provisions are not uniformly favorable to higher valuations, the balance of factors suggests that goodwill impairments will be less likely in the coming impairment cycle. To discuss how the new tax regime affects your company’s goodwill impairment more specifically, please give one of our professionals a call.

Originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Financial Reporting Update: Goodwill Impairment

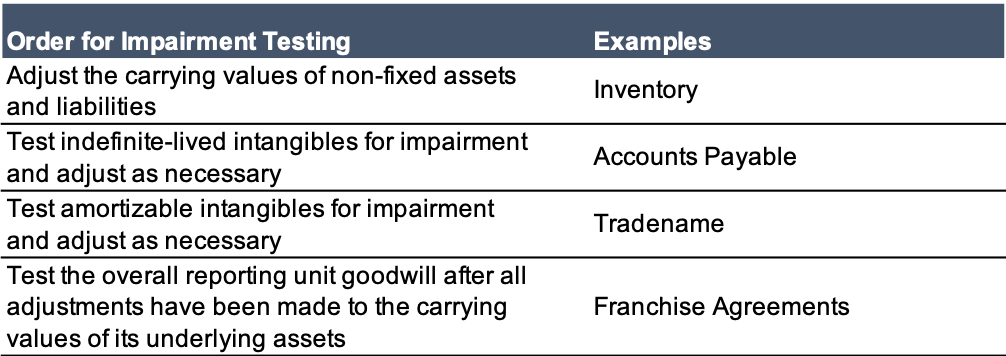

What is the Order of Testing for Impairment?

When testing the goodwill of a reporting unit for impairment, the order of operations matters. Because the units themselves may contain assets subject to impairment testing, it is important to first reflect accurate carrying values for those assets before testing the goodwill of the unit overall.

If the goodwill of the unit is tested before a write down of certain of its assets occurs, there may be increased risk of inaccurately allocating impairment between the assets and goodwill of the unit. Similarly, failing to address the order of testing could lead to the false conclusion that the goodwill of a reporting unit is impaired, when there is really only impairment of its underlying identifiable assets. These errors occur when the unit’s fair value of goodwill is compared to an inaccurately high carrying value that results from failing to adjust asset values first.

According to the AICPA Accounting & Valuation Guide: Testing Goodwill for Impairment [paragraph 2.57], the order of impairment testing should be as follows:

Financial statement preparers should not neglect the proper order of impairment testing to ensure current allocation of impairment.

Originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Financial Reporting Update: Goodwill Impairment

Financial Reporting Fallacy: The Whole May Appear Healthier Than the Parts

A logical fallacy occurs when one makes an error in reasoning. Causal fallacies occur when a conclusion about a cause is reached without enough evidence to do so. The cum hoc (“with this”) fallacy is committed when a causal relationship is assumed because two events occur together.

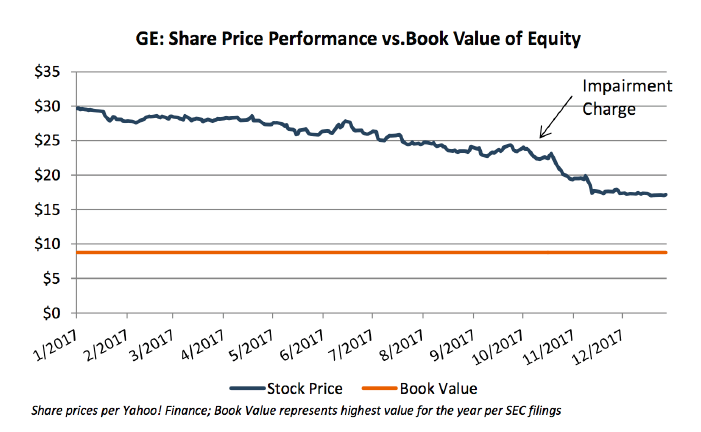

When it comes to financial reporting, an example of this fallacy would be assuming that goodwill cannot be impaired unless the company’s shares are trading below book value. This is a tempting fallacy–especially as the U.S. economy is continuing a long expansion, companies are posting solid earnings, and valuations are reaching new highs. The S&P 500 increased 19% in 2017 and the Nasdaq was up 28%. In these market conditions, goodwill impairment probably does not seem like a pressing concern. After all, goodwill is considered impaired only when fair value drops below carrying value, right? While this is true, accounting standards require that goodwill be tested for impairment at the reporting unit level. Impairment relates to a reporting unit’s ability to generate cash flows. This means that a company’s goodwill can be impaired at the reporting unit level, even as its stock trades above book value.

This was the case for multinational conglomerate General Electric last year. GE had a tumultuous 2017 as the company’s CEO and CFO departed, the dividend was cut, and a corporate restructuring was announced. The salient event for the purposes of this article is a $947 million impairment loss recorded in its Power Conversion Unit during the third quarter of 2017. This unit is what became of GE’s 2011 $3.2 billion acquisition of Converteam, an electrical engineering company. According to the company’s 2017 annual report, the causes for this impairment included downturns in marine and oil and gas markets, pricing and cost pressures, and increased competition. GE’s stock felt the turmoil, falling 42% in 2017. Shares traded at $17.25 at their lowest point, implying a market capitalization of $150.5 billion. But even at this point, GE’s stock was not trading below book value ($64.3 billion at the end of 2017). GE’s market value exceeded book value of equity by $86.2 billion. So while impairment and market value/share price are related, it is not safe to assume that there is no impairment if the stock trades above book value.