When we talk with family business owners, most confess a vague recollection of having signed a buy-sell agreement, but only a few can give a clear and concise overview of their agreement’s key terms. Yet no other governing document has such potentially profound implications for the business and for the family. My colleague of nearly twenty years, Chris Mercer, literally wrote the book(s) when it comes to buy-sell agreements. Chris and I recently sat down to talk about buy-sell agreements in the context of family businesses.

Travis: Chris, to start off, what is the purpose of a buy-sell agreement? Why should a family business have one?

Chris: A buy-sell agreement ensures that the owners of a business will have as fellow-owners only those individuals who are acceptable to the group. A buy-sell agreement formalizes agreements in the present – while everyone is alive and well – regarding how future transactions will occur, with respect to both pricing and terms, when the agreement is “triggered.”

Every business with two or more owners should have a buy-sell agreement, and that includes family businesses. What I can tell you, after many years of working with companies and their buy-sell agreements, is that once an agreement is triggered, e.g., by the death, disability or departure of a shareholder, the interests of the departed and remaining shareholders diverge. When interests diverge, an agreement is virtually impossible even, or especially, within families. So, a well-crafted buy-sell agreement establishes an agreement in advance, so the family can avoid problems and conflict in the future.

Travis: The title of your first book on buy-sell agreements described them as either reasonable resolutions or ticking time bombs. How could a buy-sell agreement become a ticking time bomb for a family business?

Chris: Sure – here’s a quick example. Some agreements specify a fixed price for shares that the shareholders have all agreed to. The price is binding until updated to a new agreed-upon price. The idea sounds good in principle, but in reality, the owners almost never agree on an updated price. Years later, after a substantial increase in a company’s value renders the agreed-upon price stale, a trigger event occurs. The ticking time bomb explodes on the departing shareholder who receives an inadequate price for their shares. A second explosion occurs with the ensuing litigation to try to “fix” the problem. Needless to say, I do not recommend the use of fixed-price valuation mechanisms in buy-sell agreements.

Travis: Buy-sell agreements often define a formula for determining value when triggered. Can a “formula price” provide for a reasonable resolution?

Chris: Travis, I’ve said many times that some owners and advisers search for the perfect formula like the Knights Templar sought the Holy Grail. The perfect formula does not exist. Given changes in the company over time, evolving industry conditions, emerging competition, and changes in the availability of financing, no formula will remain reasonable over time. It is simply not possible to anticipate all the factors an experienced business appraiser would consider at a future date. All this assumes that the formula is understandable. Some formulas in buy-sell agreements are written so obtusely that reasonable people reach (potentially quite) different results. As you might suspect, I do not recommend the use of formula pricing mechanisms in buy-sell agreements.

Travis: Other agreements provide for an appraisal process upon a trigger event. What are benefits or pitfalls of such appraisal processes?

Chris: The most common appraisal process found in buy-sell agreements calls for the use of two or three appraisers to determine the price to be paid if and when a trigger event occurs. One of the biggest problems out of the gate is that no one knows what the price of their shares will be until the end of a lengthy and potentially disastrous appraisal process.

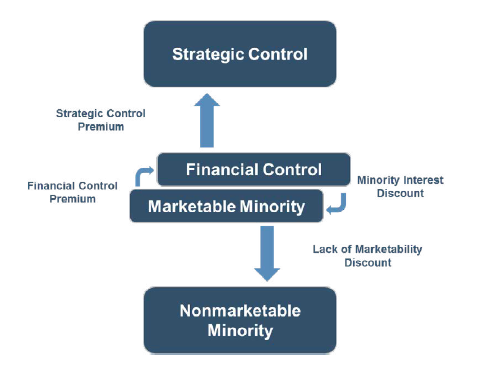

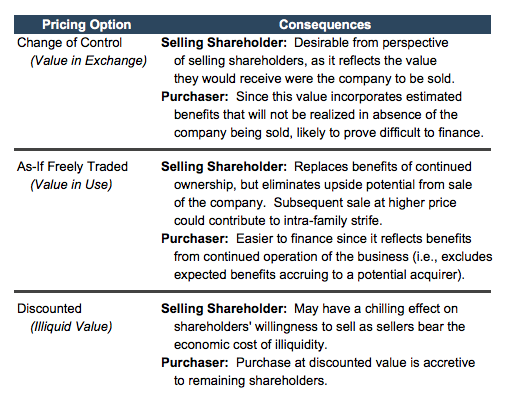

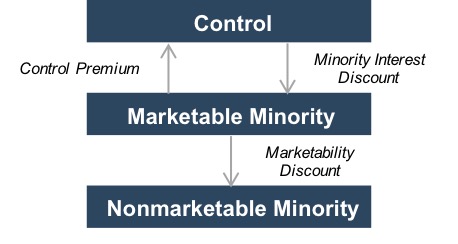

Let me explain. Assume that the shareholders have agreed on an appraisal process to determine price upon a trigger event. The Company retains one appraiser and the selling shareholder retains a second. Far too often, the language describing the type of value for the appraisers to determine is vague and inconsistent. The selling shareholder’s appraiser interprets value as an undiscounted strategic value, say $100 per share. The company’s appraiser interprets the same language as calling for significant minority interest and marketability discounts and concludes a value of, say, $40 per share. The agreement calls for the two appraisers to agree on a third appraiser who is supposed to resolve the issue. How? The two positions are not reconcilable. Litigation, unhappiness, wasted time and expense follow as the time bomb, which has been in place for years, explodes on all the parties.

Travis: So if fixed price, formula price, and appraisal process agreements all have serious drawbacks, what kind of pricing mechanism do you recommend for most family businesses?

Chris: Based on my experiences over many years, I have concluded that the best pricing mechanism for most family businesses is what I call a Single Appraiser, Select Now and Value Now valuation process. The parties agree on a single appraiser (I’d recommend Mercer Capital, of course!). The selected appraiser provides a valuation now, at the time of selection, based on the language in the buy-sell agreement. This ensures that any confusion is eliminated at the time of signing or revision. The appraisal sets the price for the buy-sell agreement until the next (preferably annual) appraisal. With this kind of process, virtually all of the problems we’ve discussed are eliminated, or reduced substantially. All the shareholders know what the current value is at any time. Importantly, they all know the process that will occur with every subsequent appraisal. The certainty provided by this Single Appraiser, Select Now and Value Now process far outweighs the uncertainty inherent in other processes at a reasonable cost. At Mercer Capital, we provide annual appraisals of over 100 companies for buy-sell agreements and other purposes.

Travis: Finally, what is your best piece of advice for family business owners when it comes to buy-sell agreements?

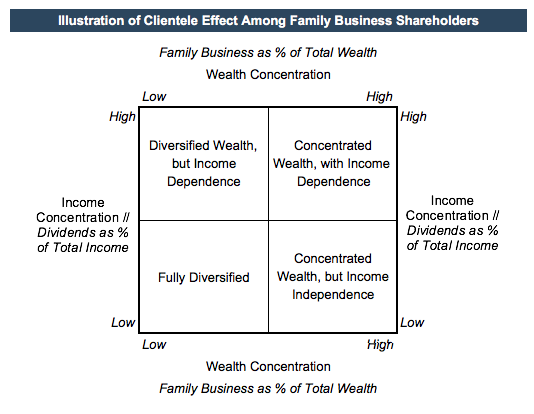

Chris: The best advice I have for family business owners is to be sure that there is an agreement regarding their buy-sell agreements. Many companies have had agreements in place for many years, often decades, without any changes or revisions. No one knows what will happen if they are triggered. Agreement regarding a buy-sell agreement should be the result of review by all shareholders, corporate counsel, and, I recommend, a qualified business appraiser. The appraiser should review agreements from business and valuation perspectives to be sure that the valuation mechanism will work when it is triggered. Discussions are not always easy, since shareholders from different generations and different branches of the family tree have differing objectives and viewpoints. Yet if all parties can agree now, the family can avoid unnecessary strife and litigation in the future. So the best advice I have is to “Just Do It!”

Conclusion

Your family’s buy-sell agreement won’t matter until it does. As families prepare for their next business meeting, leaders should carefully consider putting a review of the buy-sell agreement on the agenda.