Does Fair Market Value (and its Associated Discounts) Avoid the Intent of 2704 and Thus “Undervalue” Certain Types of Transferred Interests?

[August 2016] The IRS released its long expected proposed regulations in regards to Section 2704 on August 2. The substance of this proposal, according to the IRS, is to regulate treatment of entities for estate and gift tax purposes. According to the summary the proposal is:

“…concerning the valuation of interests in corporations and partnerships for estate, gift, and generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax purposes. Specifically, these proposed regulations concern the treatment of certain lapsing rights and restrictions on liquidation in determining the value of the transferred interests. These proposed regulations affect certain transferors of interests in corporations and partnerships and are necessary to prevent the undervaluation of such transferred interests.”

Before we delve any deeper on this article, let’s clarify a few things up front:

- We are appraisers, not lawyers and we are neither qualified nor particularly interested in dissecting the proposal from a legal perspective. Our friends in the legal community can address that.

- This is a proposal that, as of the writing of this article, is not in effect, could change, or might never go into effect. (Nonetheless we aim to comment from a valuation perspective as if it does).

With that said – what we hope to do in this post is to (i) give readers some context about the impetus of these proposed Section 2704 changes, (ii) share what these proposed changes are, and (iii) share what this might mean from a valuation standpoint.

Background of the Proposal

According to the IRS, treatment by taxpayers in regards to certain rights and transfers, as well as rulings of the Tax Court in regards to these rights and transfers have allowed taxpayers to avoid application of Section 2704. Representative of this sentiment, Page 6 of the proposal puts it this way when referencing Section 2704(b):

“The Treasury Department and the IRS have determined that the current regulations have been rendered substantially ineffective in implementing the purpose and intent of the statute by changes in state laws and by other subsequent developments.”

The areas that the IRS cites as no longer ineffective fall into three primary areas:

- 2704(a). Specifically the area covering so-called “Deathbed Transfers” – whereby liquidation rights lapse upon death. The IRS cites Estate of Harrison v. Commissioner as an example of this. The IRS claims that such transfers generally have minimal economic effects, but result in a transfer tax value that is based on less than the value of the interest.

- 2704(b). Inter-family transfers and specifically restrictions on liquidation for family interest transfers. Reasons for this include that courts have concluded that Section 2704 applies to restrictions on the ability to liquidate an entire entity, and not on the ability to liquidate a transferred interest in that entity. Also the IRS says state laws and utilization of “assignees” have allowed taxpayers avoid 2704.

- 2704(b). Granting of insubstantial interests to non-family members (such as a charity or employee) to avoid application of the statute. The IRS says this needs to be changed, because, in reality, such non-family interests generally do not constrain a family’s ability to remove a restriction on an individual interest.

Proposed Changes and Amendments

In light of this perceived avoidance and ineffectiveness of certain provisions in 2704, the IRS has proposed a number of new regulations including:

- Change the definition of a “controlled entity” to be viewed through the lens of an entire family including lineal descendants as opposed to individual(s).

- Amend the regulations to address what constitutes control of an LLC or other entity that is not a corporation, partnership, or limited partnership.

- Amend the regulations to limit the use of eliminating or lapsing rights (voting or liquidation rights) and limit the exception to transfers occurring three (3) years or more before death.

- Ignore transfer restrictions for minority interests and thus assume that they would be marketable, regardless of governing documents and/or state laws.

- Ignore the presence of non-family members with less than 10% of the overall equity value.

Valuation Impact

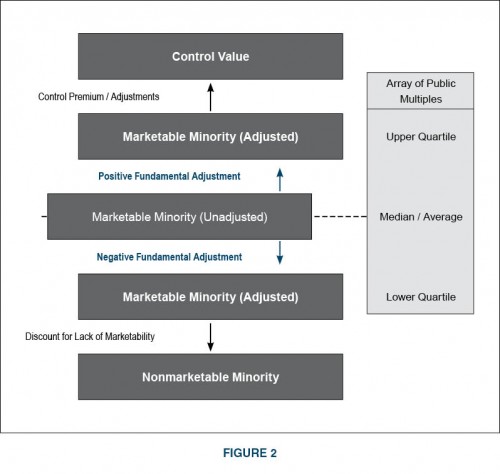

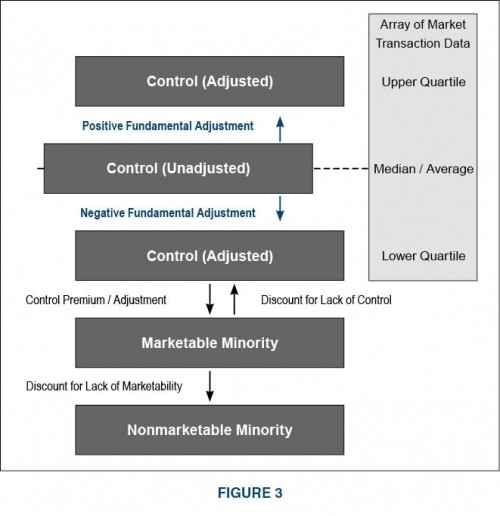

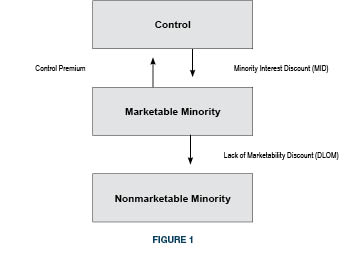

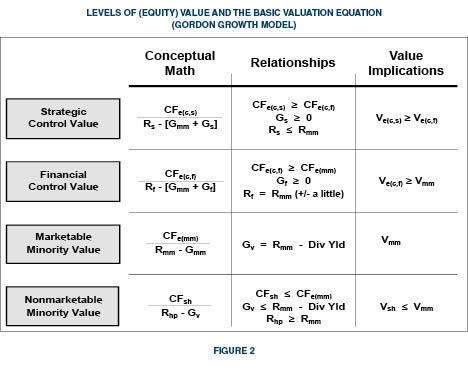

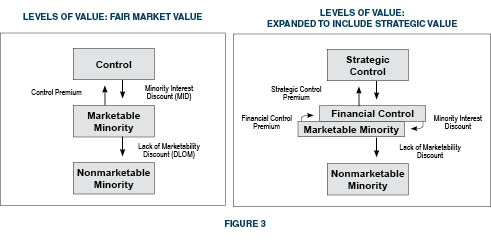

The IRS is not proposing changing the definition of fair market value. However, when applying fair market value under the constructs as contemplated in the proposed 2704 changes, there would be a smaller (or perhaps no) value delineation for minority interests as compared to enterprise value of an entity. According to the IRS’s position, this would prevent taxpayers from “undervaluing” transferred interests among family members. This, of course, runs in stark contrast to the marketplace, of which fair market value is supposed to be a reflection. The marketplace’s long track record on this is abundantly clear – it differentiates for minority interests as compared to the value of entire enterprises. Thus the proposed regulations essentially circumvent the levels of value for family members as defined in a “controlled entity.”

If the proposal is adopted as contemplated, there will be a powerful incentive for families with businesses and investment holding entities to initiate or complete transfers before these regulations take effect (which is thought to be December 2016). If Mercer Capital can be of any assistance in light of this development, please contact us.

Fairness Considerations for Mergers of Equals

When asked about his view of a tie years before the NCAA instituted the playoff format in the 1990s, Coach Bear Bryant famously described the outcome as “kissing your sister.” If he were a portfolio manager holding a position in a company that entered into a merger of equals (MOE), his response might be the same. Wall Street generally does not like MOEs unless the benefits are utterly obvious and/or one or both parties had no other path to create shareholder value. In some instances, MOEs may be an intermediate step to a larger transaction that unlocks value. National Commerce Financial Corporation CEO Tom Garrott once told me that part of his rationale for entering into a $1.6 billion MOE with CCB Financial Corp. in 2000 that resulted in CCB owning 47% of the company was because bankers told him he needed a bigger retail footprint to elicit top dollar in a sale. It worked. National Commerce agreed to be acquired by SunTrust Banks, Inc. in 2004 in a deal that was valued at $7 billion.

Kissing Your Sister?

MOEs, like acquisitions, typically look good in a PowerPoint presentation, but can be tough to execute. Busts from the past include Daimler-Benz/Chrysler Corporation and AOL/Time Warner. Among banks the 1994 combination of Cleveland-based Society Corporation and Albany-based KeyCorp was considered to be a struggle for several years, while the 1995 combination of North Carolina-based Southern National Corp. and BB&T Financial Corporation was deemed a success.

The arbiter between success and failure for MOEs typically is culture, unless the combination was just a triumph of investment banking and hubris, as was the case with AOL/Time Warner. The post-merger KeyCorp struggled because Society was a centralized, commercial-lending powerhouse compared to the decentralized, retail-focused KeyCorp. Elements of both executive management teams stuck around. Southern National, which took the BB&T name, paid the then legacy BB&T management to go away. At the time there was outrage expressed among investors at the amount, but CEO John Allison noted it was necessary to ensure success with one management team in charge. Likewise, National Commerce’s Garrott as Executive Chairman retained the exclusive option to oust CCB’s Ernie Roessler, who became CEO of the combined company, at the cost of $10 million if he chose to do so. Garrett exercised the option and cut the check in mid-2003 three years after the MOE was consummated.

Fairness Opinions for MOEs

MOEs represent a different proposition for the financial advisor in terms of rendering advice to the Board. An MOE is not the same transaction as advising a would-be seller about how a take-out price will compare to other transactions or the company’s potential value based upon management’s projections. The same applies to advising a buyer regarding the pricing of a target. In an MOE (or quasi-MOE) both parties give up 40-50% ownership for future benefits with typically little premium if one or both are publicly traded. Plus there are the social issues to navigate.

While much of an advisor’s role will be focused on providing analysis and advice to the Board leading up to a meaningful corporate decision, the fairness opinion issued by the advisor (and/or second advisor) has a narrow scope. Among other things a fairness opinion does not opine:

- The course of action the Board should take;

- The contemplated transaction represents the highest obtainable value;

- Where a security will trade in the future; and

- How shareholders should vote.

What is opined is the fairness of the transaction from a financial point of view of the company’s shareholders as of a specific date and subject to certain assumptions. If the opinion is a sell-side opinion, the advisor will opine as to the fairness of the consideration received. The buy-side opinion will opine as to the fairness of the consideration paid. A fairness opinion for each respective party to an MOE will opine as to the fairness of the exchange ratio because MOEs largely entail stock-for-stock structures.

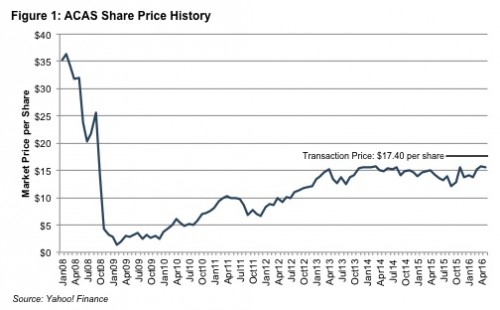

Explaining the benefits of an MOE and why ultimately the transaction is deemed to be fair in the absence of a market premium can be challenging. The pending MOE among Talmer Bancorp Inc. (45%) and Chemical Financial Corp. (55%) is an example. When the merger was announced on January 26, the implied value for Talmer was $15.64 per share based upon the exchange ratio for Chemical shares (plus a small amount of cash). Talmer’s shares closed on January 25, 2016 at $16.00 per share. During the call to discuss the transaction, one analyst described the deal as a “take under” while a large institutional investor said he was “incredibly disappointed” and accused the Board of not upholding its fiduciary duty. The shares dropped 5% on the day of the announcement to close at $15.19 per share.

Was the transaction unfair and did the Board breach its fiduciary duties (care, loyalty and good faith) as the institutional shareholder claimed? It appears not. The S-4 notes Talmer had exploratory discussions with other institutions, including one that was “substantially larger”; yet none were willing to move forward. As a result an MOE with Chemical was crafted, which includes projected EPS accretion of 19% for Talmer, 8% for Chemical, and a 100%+ increase in the cash dividend to Talmer shareholders. Although the fairness opinions did not opine where Chemical’s shares will trade in the future, the bankers’ analyses noted sizable upside if the company achieves various peer-level P/Es. (As of mid-July 2016, Talmer’s shares were trading around $20 per share.)

Fairness is not defined legally. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “fair” as “just, equitable and agreeing with what is thought to be right or acceptable.” Fairness when judging a corporate transaction is a range concept. Some transactions are not fair, some are in the range—reasonable, and others are very fair.

The concept of “fairness” is especially well-suited for MOEs. MOEs represent a combination of two companies in which both shareholders will benefit from expense savings, revenue synergies and sometimes qualitative attributes. Value is an element of the fairness analysis, but the relative analysis takes on more importance based upon a comparison of contributions of revenues, earnings, capital and the like compared to pro forma ownership.

Investment Merits to Consider

A key question to ask as part of the fairness analysis: are shareholders better off or at least no worse for exchanging their shares for shares in the new company and accepting the execution risks? In order to answer the question, the investment merits of the pro forma company have to be weighed relative to each partner’s attributes.

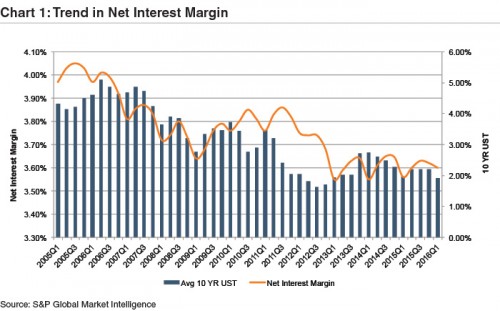

- Profitability and Revenue Trends. The analysis should consider each party’s historical and projected revenues, margins, operating earnings, dividends and other financial metrics. Issues to be vetted include customer concentrations, the source of growth, the source of any margin pressure and the like. The quality of earnings and a comparison of core vs. reported earnings over a multi-year period should be evaluated.

- Expense Savings. How much and when are the savings expected to be realized. Do the savings come disproportionately from one party? Are the execution risks high? How does the present value of the after-tax expense savings compare to the pre-merger value of the two companies on a combined basis?

- Pro Forma Projected Performance. How do the pro forma projections compare with each party’s stand-alone projections? Does one party sacrifice growth or margins by partnering with a slower growing and/or lower margin company?

- Per Share Accretion. Both parties of an MOE face ownership dilution. What is obtained in return in terms of accretion (or dilution) in EBITDA per share (for non-banks), tangible BVPS, EPS, dividends and the like?

- Distribution Capacity. One of the benefits of a more profitable company should be (all else equal) the capacity to return a greater percentage of earnings (or cash flow) to shareholders in the form of dividends and buybacks.

- Capital Structure. Does the pro forma company operate with an appropriate capital structure given industry norms, cyclicality of the business and investment needs to sustain operations? Is there an issue if one party to an MOE is less levered and the other is highly levered?

- Balance Sheet Flexibility. Related to the capital structure should be a detailed review of the pro forma company’s balance sheet that examines such areas as liquidity, funding sources, and the carrying value of assets such as deferred tax assets.

- Consensus Analyst Estimates. This can be a big consideration in terms of Street reaction to an MOE for public companies. If pro forma EPS estimates for both parties comfortably exceed Street estimates, then the chances for a favorable reaction to an MOE announcement improve. If accretion is deemed to be marginal for the risk assumed or the projections are not viewed as credible, then reaction may be negative.

- Valuation. The valuation of the combined company based upon pro forma per share metrics should be compared with each company’s current and historical valuations and a relevant peer group. Also, while no opinion is expressed about where the pro forma company’s shares will trade in the future, the historical valuation metrics provide a context to analyze a range of shareholder returns if earning targets are met under various valuation scenarios. This is particularly useful when comparing the analysis with each company on a stand-alone basis.

- Share Performance. Both parties should understand the source of their shares and the other party’s share performance over multi-year holding periods. For example, if the shares have significantly outperformed an index over a given holding period, is it because earnings growth accelerated? Or, is it because the shares were depressed at the beginning of the measurement period? Likewise, underperformance may signal disappointing earnings, or it may reflect a starting point valuation that was unusually high.

- Liquidity of the Shares. How much is liquidity expected to improve because of the MOE? What is the capacity to sell shares issued in the merger? SEC registration and even NASADQ and NYSE listings do not guarantee that large blocks can be liquidated efficiently.

- Strategic Position. Does the pro forma company have greater strategic value as an acquisition candidate (or an acquirer) than the merger partners individually?

Conclusion

The list does not encompass every question that should be asked as part of the fairness analysis for an MOE, but it points to the importance of vetting the combined company’s investment attributes as part of addressing what shareholders stand to gain relative to what is relinquished. We at Mercer Capital have over 30 years of experience helping companies and financial institutions assess significant transactions, including MOEs. Do not hesitate to contact us to discuss a transaction or valuation issue in confidence.

Analyzing Financial Projections as Part of the ESOP Fiduciary Process | Appraisal Review Practice Aid for ESOP Trustees

This article first appeared as a whitepaper in a series of reports titled Appraisal Review Practice Aid for ESOP Trustees. To view or download the original report as a PDF, click here.

This publication provides general insight about emerging issues and topics discussed in recent forums and events sponsored by the ESOP Association (“EA”), The National Center for Employee Ownership (“NCEO”) and elsewhere. Much of the current discussion is related to general valuation discipline, but none are new to a longstanding agenda within the ESOP community. Heightened Department of Labor (“DOL”) attention and the recent settlement agreement concerning the Sierra Aluminum case are driving renewed discussion of numerous critical topics within the ESOP fiduciary domain.

All guidance, perspective and other information contained in this publication is provided for information purposes only. The issues and treatments highlighted in this publication do not produce the same response from all ESOP professionals and valuation practitioners. Certain treatments and perspectives contained herein lack consensus in the valuation profession and may be addressed or treated using alternative rationales. This publication is not held out as being the position of or recommended treatment endorsed by the EA or the NCEO. The purpose of this publication is to alert and inform ESOP stakeholders and fiduciaries regarding the rising standards of practice and prudence in the valuation of ESOP owned entities.

Introduction

In recent years there has been increasing concern among ESOP sponsors and professional advisors (trustees, TPAs, business appraisers, legal counsel) regarding the scrutiny of the DOL, the Employee Benefits Security Administration (“EBSA”), and the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”). These entities (and agencies thereof) are tasked with ensuring that ESOPs comply with the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (“ERISA”) as well as with various provisions of the federal income tax code concerning qualified retirement plans (including ESOPs). Citing concerns for poor quality and inconsistency in business appraisals, the DOL has sought in recent years to expand the meaning of “fiduciary” under ERISA to include business appraisers. In the most recent forums of exchange and deriving from various court actions, there are numerous areas of concern that DOL/EBSA appear to have regarding ESOP valuations. These areas of focus include but are not limited to:

Valuation Issues Receiving Recent Attention and Scrutiny

- The use of financial projections in ESOP valuation

- The prevalence and manifestation of conflicts of interest concerning pre- and post-transaction advisory services

- The use and application of control premiums in ESOP valuation

- The valuation of and implications stemming from seller financing used in a great many transactions now coming under review

- The poor quality of ESOP valuation reports and the attending inconsistencies between narrative explanations and methodological execution; and,

- The lack of or inconsistent consideration of ESOP repurchase obligation and how it interacts with ESOP valuation

These topics have received heightened attention from numerous committees of the ESOP Association including the Advisory Committees on Valuation, Administration, Fiduciary Issues, Finance, and Legislative & Regulatory. This paper will focus on the use of financial projections in ESOP valuations. While all of the cited issues are of importance, the use (or misuse) of financial projections is often the most direct cause of over- or under-valuation in ESOPs. Other Mercer Capital publications provide insight regarding control premiums, the market approach, and other important ESOP valuation topics.

Projections Used In ESOP Valuations: Assessing Growth Rate Assumptions In Valuation

Business appraisers who practice valuation using one or more credentials in the field are required to adhere to their respective practice standards (ASA, AICPA, NACVA, CFAI). Additionally, there are overarching standards and guidance that generally dictate to and govern the valuation profession and the general considerations and content of a business valuation. The Appraisal Standards Board of The Appraisal Foundation promulgates the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (“USPAP”) and the IRS issued Revenue Ruling 59-60 (“RR59-60”) more than 50 years ago.

Collectively, these standards and protocols provide a basic outline for procedural disciplines, analytical methodologies, and reporting conventions. Specificity on the disciplines and procedures for vetting a financial projection (and growth rates in general) are generally lacking in the body of valuation standards, but that does not exempt appraisers and trustees from the core principle that a valuation must collectively (and in its constituent parts) constitute informed judgment, reasonableness and common sense.

Traditional financial and economic comparative analysis suggest vetting a projection by way of studying it from numerous perspectives:

- How do the projections compare to the historical and prevailing financial performance of the subject enterprise being valued (“relative to itself over time”)?

- How do the forecasted results compare to the past and expected performance of peers, competitors, the industry, and the marketplace in general (“relative to others over time”)?

- How do the projections reflect the specific outlook and capacity of the subject enterprise (“relative to its specific opportunity”)?

The answers to these questions provide the appraiser a foundation upon which to construct the other required modeling elements in the valuation. An appraiser may elect to disregard projections in the valuation process in situations where forecasted outcomes are deemed beyond the organic and/or funded capacities, competence, and/or opportunity of the subject enterprise. An appraiser may elect to consider justifiable risk and/or probability assessments, among other adjustments, that serve to hedge the projections and their respective influence on the conclusions of the valuation report.

Regarding valuation and the general concern for rendering valuations that heighten an ESOP trustee’s anxiety for a sustainable ESOP benefit over time, many appraisers elect to capture only proven performance capacity, avoiding the counting of eggs with questionable fertility. If today’s projection proves excessive in the light of future days (when the DOL/EBSA comes calling), the concern for a prohibited transaction rises and poses significant risk and potentially fatal consequences for the plan and the parties involved.

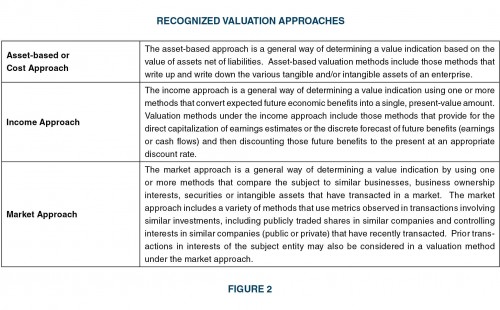

Discrete Projections versus Implied Projections

A complete, formal appraisal opinion requires the consideration of three core valuation approaches. These approaches are the Cost, Income, and Market Approaches. Generally speaking, valuations of business enterprises using the Income or Market Approaches contain either an explicit projection in the methodology or capture an underlying implicit projection embedded in (or implied by) a singular perpetual growth rate assumption or in a singular capitalization metric. Appraisers and reviewers that fail to recognize this are simply blind to the basic financial mechanics of income capitalization. Accordingly, the concern for projections, in the view of this practitioner, extends beyond the discrete modeling of cash flow to the broader domain of growth in general. For the sake of further discussion, assume the following comments relate specifically and only to the Income Approach and its underlying methods.

Discounted Cash Flow Method versus Single-Period Capitalization

The size and sophistication of the subject enterprise often dictates whether or not an appraiser will enjoy the benefit of management-prepared projections. Projections are often crafted for purposes of promoting operational and marketing outcomes, or for satisfying the reporting requirements that many companies have with their lenders, shareholders, suppliers and other stakeholders. In cases where the subject enterprise is small and its performance subject to unpredictable patterns, appraisers commonly employ a single period capitalization of cash flow or earnings. In lieu of a series of discrete cash flows projected over the typical five-year future time horizon, the appraiser simply employs a measure of current or average performance and applies a single-period capitalization rate (or capitalization multiple as the case may be) in order to convert a base measure of cash flow directly into an indication of value. Seeking not to speculate on a finite sequence of future growth rates, many appraisers employ a rule-of-thumb mentality by correlating cash flow growth to a macroeconomic, inflationary, or industry-motivated rate, often ranging from 3% to 5%. In many instances this could be appropriate; in others it could reflect surprisingly little attention regarding the most basic long-term market externalities and/or internal opportunities of the subject company.

The veil of a single-period capitalization approach does not relieve the appraiser from examining the various combinations of growth that could reasonably apply to the base measure of cash flow assumed in an appraisal. Many appraisers are of the mind that in the absence of management-prepared projections, no discrete projection can be developed and thus no Discounted Cash Flow Method can be employed. In lieu of fleshing out the dynamics of operational cash flow, the required capital investments, working capital needs, or the cash flow benefits deriving therefrom, the appraiser simply defaults to the time-honored single period capitalization of cash flow and calls it a day. The binary position that an appraiser cannot prepare cash flow projections lacks credibility and in some cases is simply flawed thinking. Furthermore, any appraiser that applies a perpetual growth rate assumption to develop a capitalization rate is, in fact, asserting a projection over some projection horizon. This is the simple and inescapable mathematical construct that is the Gordon Growth Rate Model. With all due respect and concern about projections – appraisers, trustees and regulators must recognize the inherent projection represented by a perpetual growth rate assumption in a single-period capitalization method. In essence, there is no income approach without either an explicit or implicit projection of future cash flows.

Performing Due Diligence On Company Issued Projections

Imagine you are a trustee tasked with reviewing an ESOP valuation prepared by the plan’s “financial advisor.” Business appraisers in their role as the trustee’s financial advisor issue opinions of value they believe to be supported by the facts and circumstances, but ultimately the appraisal of the plan assets is the trustee’s responsibility. How can the stakeholders and fiduciaries of an ESOP gain understanding and comfort in projections prepared by the Company and employed by the appraiser?

The foundation begins with the general process of examining historic and prospective growth. Company projections must make sense to gain inclusion in the valuation of an ESOPowned company. A disconnect or sudden shift (whether in magnitude, trend or directionality) in expected performance is a red flag that requires specific explanation. Absent a sound rationale for a significant change in the pattern of future performance, projections that seem too good (or too bad) to be true must be reconciled with management and potentially disregarded in the appraisal process.

Not all projections are created equally. Some are prepared for budgetary purposes and are constrained to a single year of outlook. Projections may be prepared for many reasons including the study of operational capacity, financial feasibility concerning capital investments, debt servicing and lender requirements, sales force management, incentive compensation, and many other reasons. Projections may be the product of a bottom-up process (originating in the operational ranks of the business) or may originate as a top-down exercise (descending from the C suite).

Business appraisers cannot be indiscriminate in their employment of forward-looking financial information. Understanding the goals, intentions, motivations, and possible shortcomings of a budget or projection is vital to assessing the viability of a direct or supporting role for the projections in the valuation modeling. The nature and maturity of the business are also significant to understanding and troubleshooting a projection. For the sake of further commentary we will assume that most ESOP companies are relatively mature and not subject to the intricacies and uncertainties of valuing a start-up business (albeit, even mature business can experience significant swings in business activity).

Projection Due Diligence Inquiries

- Who prepared the projections?

- What is the functional use or purpose of the projection?

- How experienced is the Company in preparing projections?

- When were the projections prepared?

- Do the projections incorporate increased (new) business, and if so, in what manner is the new business being generated?

- Do the projections reflect the discontinuation of specific segments of the revenue stream?

- Are the financial projections reconciled to or generated from a meaningful expression of unit volume and pricing?

- Does the company operate as the exclusive or concentrated agent for certain suppliers and/or customers?

- How does the company’s current projection reconcile to past projections?

- How closely does the company’s most recent actual performance compare to the prior year’s projection?

- Does the projection depict a transition in industry or economic cycles that may justify near-term abrupt shifts in expected outcomes?

- How comprehensive are the projections and the supporting documentation?

- What are some typical warning signs that a projection may be too aggressive or pessimistic?

Who prepared the projections?

A bottom-up process whereby front-line managers project their respective business results, which are then combined to create a consolidated projection, is often the most informative projection. Motivation mindset can be important as many projections are designed to “under-promise” results. Conversely, some projections are deliberately overstated to impart a mission of growth or goal-oriented outcomes. Projections that emanate and evolve through multiple levels of an organization are typically subject to more checks and balances than projections that originate in the vacuum of a single executive’s office. Conversely, such a process can also depict an organizational mob mentality that could distort reasonable expectations.

A CFO’s budget may vary significantly from the sales projection of a sales manager or the projections of a senior executive. In some cases, an appraiser may review projections prepared for a lender that vary from a strategic plan projection. Often the differences can be reconciled. Projections prepared for external stakeholders such as lenders and as communicated to shareholders and possibly endorsed by a board of directors are likely to be the most relevant and appropriate for the valuation.

If numerous projections exist, the trustee and appraiser are best advised to inquire about the outlook that best reflects a consensus of the most likely outcome as opposed to aspirational projections that are tied to new and/or speculative changes in the business model. In a recent engagement, a client was deploying significant capital to extend core competencies into adjacent markets. Rather than the hockey stick of growth most typical of such projections, this client’s net cash flows were relatively neutral in the foreseeable future because they included significant capital and working capital investment, which effectively paid for increased business volume. The premise behind their strategy was simply one of being larger and more diverse under the assumption that size and diversity facilitated a less risky business proposition and a broader range of potential long-term outcomes for the business.

What is the functional use or purpose of the projection?

Functional use is often linked to who prepares the projection. Be wary of projections that may intentionally (or as a byproduct of purpose) under or over shoot actual expected forecast results. In many cases a bottom-up projection process receives the review of senior management before becoming a functional element of business planning and accountability.

How experienced is the Company in preparing projections?

Are past projections reconciled to actual results with adequate explanation for variances? Firms with consistent and organized processes often produce more informative projections. Granted, a company may consistently under or over perform their projection. The quality of a projection may be better measured by its consistency over time than by its ultimate accuracy in a given year. One clue to the experience and care taken in the projection process is the model underlying the projection itself. For example, was the forecast model developed using numerous discrete modeling assumptions (such as year-to-year growth, and year-to-year margin) or from more global assumptions that are carried across all years in the projections? While modeling complexity can serve to obscure and is not automatically a sign of a well-developed projection, the inability of a projection model to be adapted quickly to alternative scenarios and assumptions may be a sign that the model was not studied for its sensitivity and reasonableness. A projection that appears to be “living” and easily modified could be a sign that the company actually uses the projection and modifies it in real time to assess variance and to modify assumptions as business conditions evolve and change. Appraisers and trustees should empower themselves with the ability to study the sensitivity and outcomes of a projection. Projections that lack detailed growth and margin details (year-to-year and CAG) should be replicated and/or reverse engineered in some fashion to facilitate basic stress testing and/or sensitivity analysis before the appraiser simply accepts the projections.

When were the projections prepared?

In general, valuation standards call for the consideration of all known or reasonably knowable information (financial, operational, strategically or otherwise) as of the effective date of the appraisal, which for most ESOPs is the end of the plan year. As a matter of practicality, financial statements (audits and tax returns) are not prepared for many months subsequent to the plan year end. Likewise, projections are often compiled in the first few months of the following year and may be influenced by the momentum of activity after the valuation date.

Appraisers typically cite financial information delivered after the valuation date to be known or knowable and projections, while potentially exposed to a hint of subsequent influence, are often integrated without much question regarding their timeliness to the valuation date. In many cases, clients struggle to get information to us in order for their 5500s to be filed in a timely fashion (typically July 31st). In most cases we find that projections prepared after the end of the plan year are perfectly fine to employ. We inquire with management if there are aspects of the projection that were influenced by subsequent events and if so, with what degree of certainty could the subsequent event or activity have been expected at the valuation date. In some situations it may be advisable or reasonable to alter a projection’s initial year due to subsequent influences; typically the more distant years of a projection follow a pattern of knowable expectation unless there has been a material subsequent event that alters the global posture of the business. If a material subsequent event occurs that is not factored into the projections, then as a matter of common sense, the appraiser may elect not to perform a DCF, or better yet, may request that the projections be modified to take the event into financial consideration so that a DCF can be more accurately informed regarding changes in business posture.

Do the projections incorporate increased (new) business, and if so, in what manner is the new business being generated?

If a projection reflects a pattern of significant change in business activity, it is vital to consider whether new business represents an extension or replication of past expansions. If the company has proven the ability to expand and absorb new business (territory, staffing, productive capacity, etc.) then a projection depicting such an increase is likely reasonable, but should be gauged by past similar experiences whenever possible. And, any business expansion must be reflected in the investment and working capital charges applied to develop net cash flows. We refer to this as “buying the growth” – remember there is no free lunch.

Projections with significant topline and profit growth must reflect adequate investment. This investment may take the form of the organic investment in the existing business lines or strategically by way of acquisition. If the projections include a speculative expansion into new revenue areas, the appraiser should properly assess the likelihood of successfully achieving the projection. Business extensions into logical adjacencies which leverage pre-existing supply and customer relationships may be more believable than the widget company whose projections include entry into the healthcare industry.

In cases where projections include speculative ventures, the appraiser has numerous potential treatments that can temper speculative (high-risk) contributions, essentially replicating the framework applied in the valuation and capital raising processes for start-ups or early-stage companies. In some cases the appraiser may request the projection be revised to eliminate contributions from new growth projects that lack adequate investment or are simply too speculative to consider until they become observable in the reported financial results of the business. In some rare cases, not only is the projection hard to believe, but concerns are compounded by the risky and foolish deployment of capital. Betting the farm on the next reinvention of the wheel is not the making of a sustainable ESOP company.

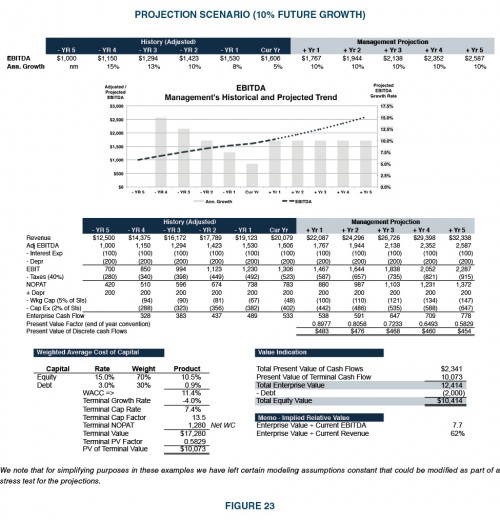

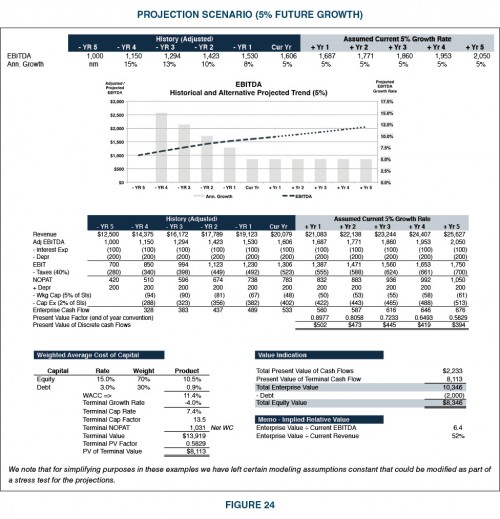

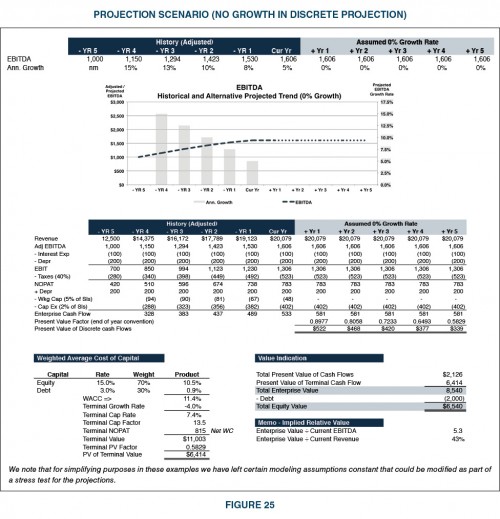

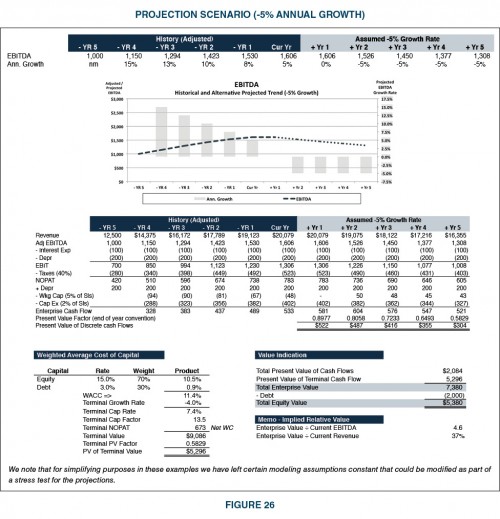

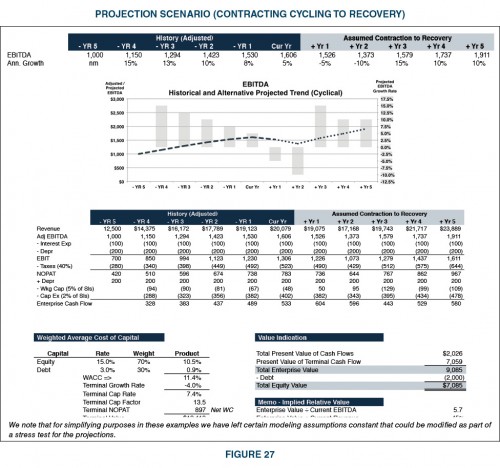

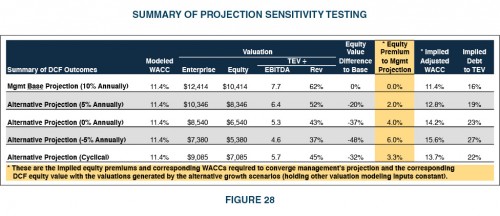

Perhaps it’s a dirty little secret in the hard-to-value world of closely held equity, but valuations using the standard of fair market value (as called for under DOL guidance) are inherently lagging in nature and typically less volatile than is the stock market or the public peers to which a company may be benchmarked. This is generally a function of regression to the mean captured in virtually every conservatively constructed projection and DCF model. The terminal value of a DCF is effectively a deferred single period capitalization using the Gordon Growth Model and often comprises 50% or more of the total value indicated under the method. Near-term performance swings (whether favorable or not) get smoothed out in the math of the terminal value calculation. As depicted in the appended growth scenarios and projection modifications, the regression of future performance to a targeted benchmark can have a similar influence on valuation as the old-guard habit of using historical averages in a single period capitalization method. The primary valuation differences between such a DCF and single period capitalization stem from the specific cash flows during the discrete projection period (years one through five).

Do the projections reflect the discontinuation of specific segments of the revenue stream?

A sound reason for employing a DCF model is to capture the pro forma performance of a business based on its going-forward revenue base. Most mid to large sized businesses, particularly mature ESOP companies, experience contraction and rationalization of business lines and markets over time. In many cases, the valuation might reasonably improve based on the discontinuation of unprofitable operations and the recapturing of poorly deployed capital. However, care must be taken to understand how all P&L accounts from revenue down to profit are affected by changes in facilities, products, services, staffing, etc. Projections that pretend unsupportable improvement by way of the deletion of a relatively small portion of the business lines are inclined to excessive optimism and may suggest the belief in bigger issues that management deems too daunting to fix. Regarding profitability, so-called “addition through subtraction” is similar to the concern public market investors have with public companies that cut expense merely to manufacture earnings in the near term. As the maxim goes, you can’t cut your way to success in the business world.

Are the financial projections reconciled to or generated from a meaningful expression of unit volume and pricing?

Financial projections that lack an operational perspective can be difficult to assess. Not all business are margin based, many are spread based – meaning that profits are more of a function of a nominal spread over cost as opposed to some percentage of sales. This is particularly true of service businesses, financial services entities, and commodity driven operations. Accordingly, neither past nor future performance can be properly understood without some idea of how much stuff is getting sold and at what price. In many cases, the required comfort level of a projection simply cannot be reached without it. Breaking revenue into primary volume and price components, as well as further into its departmental or categorical groupings, allows appraisers and trustees a better understanding of the projection and its relation to past performance and market expectations. Revenue per full-time equivalent employee, units produced per labor hour and many other performance metrics are helpful in teasing out reality from a potentially fictional projection.

Does the company operate as the exclusive or concentrated agent for certain suppliers and/or customers?

Our comments here exclude the consideration of risk associated with high levels of concentration on the rain-making parts of a business – such considerations are often tackled in the appraiser’s assessment of the cost of capital by way of firm-specific risk.

Many dealerships, distributors, parts manufacturers, fabricators and service companies owe their existence to market demand created by their suppliers and customers. Many companies service the needs of customers and suppliers by effectively outsourcing some aspect of their respective industry model to an external provider. For example, a producer of value-added materials may use an external company to provide sales and logistical support to get product to its end users (i.e. classic bulk breaking, repacking and transportation). Regardless of which leg of the multi-leg industry the subject business may represent, the assessment of projected growth should include a consideration of what is happening to suppliers and customers (the other legs of a common stool). This same path of inquiry serves the dual purpose of understanding the risk side of the valuation equation. If these multiple legs of consideration don’t reconcile, the projection could prove too unstable for use in the valuation.

How does the company’s current projection reconcile to past projections? How closely does the company’s most recent actual performance compare to the prior year’s projection?

Studying projection variance can be a highly useful tool in communicating about value and in assessing the correlation between expectations and actual results. Let’s face it – we all like it when people do what they say they are going to do. But the first thing we know about any projection today is that it will be wrong tomorrow. Variances need to be explained and reconciled against the continuing willingness of the appraiser (and the trustee) to employ projections moving forward. Providing financial feedback to management and the trustee during the process of due diligence and in the form of a valuation can help refine the projection process over time. Just as we reserve the right to improve how we do things in the valuation world, so too must our clients have the leeway to refine and improve their processes.

Valuation is a forward looking (ex-ante) discipline. History can be highly instructive regarding how projections are scrutinized in real time. Projections that under-promise and over-deliver tend to undervalue companies in real time. Conversely, projections that over-promise and under-deliver can lead to an over-statement of value. In the case of the later occurrence, most appraisers operate under the axiom of “fool me once shame on you, fool me twice shame on me.” Ultimately, attempts at value engineering via optimistic projections need to be balanced with an equal measure of devil’s advocacy from both appraiser and trustee. Ultimately, a DCF model views the impact of any projection through a risk-adjusted lens. The process of hedging a projection generally begins with an observation of historical variances in projected performance and actual results over time, with the primary emphasis place on most recent periods. Projections that appear to overshoot are often hedged either through risk assessment, probability factoring, or a more exotic multi-outcome analysis.

Does the projection depict a transition in industry or economic cycles that may justify near-term abrupt shifts in expected outcomes?

In recent decades the concept of the traditional five-year business cycle lost favor in some circles. Thought evolution evolved to encompass a lengthier cycle of ten years, mitigated volatility (not so high and not so low as in the past), higher fundamental causation (such as globalization) versus the classical cyclical drivers (such as swings in productivity), continuing evolution of the information sector, disruptive technologies, and since the early 2000s, the persistence of and sensitivity to geopolitical and terrorist events. Then along came the debt crisis followed by the great recession. Lessons of business cycles past have now garnered renewed attention and distant economic history seemed more relevant despite the modernization, globalization and regulation of the economy.

Presently, we are witness to a reasonably stable economy that is slowly being weaned from years of fiscal and monetary life support and subsidization. For us business appraisers, we are beginning to lock in on the new norms of our clients’ businesses. For the last many years, our clients were reticent to speculate on a projection (“no visibility”). Many clients recall with anger and humility the great glory projected from atop the last peak cycle in 2006. Almost a decade later, many have finally re-achieved their former glory. Many others can only look up from the corporate grave. From this point forward we can only assume that some version of the business cycle is still with us. Many are now disposed to the concept of a prolonged period of relatively modest and unevenly distributed economic performance, similar to the patterns demonstrated by Japan and characterized as “secular stagnation.” The academicians can argue about how to brand it; valuations professionals and ESOP Trustees are faced with how to consider it in our valuations.

Speaking from personal experience, there is a greater appreciation for industry cycles as opposed to macroeconomic cycles. Given such, we see companies vacillate between boom and bust based on numerous underlying elements and drivers that are not purely correlated to the overall economy. Recall the classic business cycle (peak / contraction / trough / expansion / peak). Appraisers and trustees must be attentive and weary of projections that cannot be supported by reasonable facts and circumstances. Some may wonder – when are projections unrealistic? The truthful answer often includes the echo: “not sure, but I know it when I see it.”

Companies emerging from the trough of a business/industry cycle may have unusually robust projections. High growth during a period of recovery does not constitute grounds for the dismissal of the projection. Likewise, declining growth from a peak level of performance is not necessarily overly pessimistic. As discussed in the growth scenarios studied in the appended examples, regression to a mean level of future expectation can be achieved in varying ways. The concern for appraisers and trustees alike is the comfort and common sense of near-term expectations relative to recent performance and the level of steady-state performance assumed in the terminal value modeling of the DCF. Ex-post and ex-ante trend analysis, as well as benchmarking to relevant indices from both public and private sectors is vital to establishing the context of a specific projection.

On the weight of evidence and common sense, if a projection is highly contrary to external expectations and lacks symmetry with the proven capabilities of the company, appraisers and trustees are cautioned from directly using the projection. An alternative approach for employing the projection is iterating the discount rate and terminal value modeling assumptions required to equate the DCF value indication to value indications developed from other methods (past and present). There are many instances when data lacks reliability during a given period or cycle. In such cases we tend to study the information and reconcile it to the alternative valuation results deemed more reliable. In this fashion we alert the report reviewer that projections exist that may appear contrary to the weight of history and/or external expectations.

How Comprehensive are the Projections and the Supporting Documentation?

Are the projections lacking detail and limited in supporting documentation? Projections that are not integrated into a full set of forward looking financial statements and that lack explanation for critical inputs may be unreliable or require significant augmentation before being integrated into a DCF valuation model. As a matter of practicality, many companies do not project more than a simple income statement. Does the lack of a balance sheet and a cash flow statement automatically exclude the projection from consideration? Not in my view, however, under many circumstances there could be a need for augmentation to consider numerous significant aspects required to develop the typical DCF model. These considerations include:

- Capital expenditures, which initially decrease cash flow before generating the returns that constitute future growth. Not only is the dollar amount a significant consideration, but the capacity/volume effect of physical additions relates to future growth modeling.

- Incremental working capital requirements, which typically absorb a portion of growth dollars in perpetuation of higher operating activity, or which may accumulate on the balance sheet in a downturn when demand for financial resources can temporarily decline.

- In cases where a DCF is used to directly value the equity of an enterprise, changes in net debt must be captured. Are the cash flows sufficient to cover the company’s term debt and line of credit obligations? Are new sources of debt capital required to support capital and working capital grow?

Collectively, these cash flow attributes can have a significant effect on the discrete cash flows of an entity during the projection. Absent a balance sheet and/or cash flow statement, the impact of these considerations may be difficult to properly assess. In cases where the business is not deploying significant new capital and the projection is following a more or less mature pattern, capital expenditures and incremental working capital may be easily determined based on historical norms and comparative analysis with peer data. Accordingly, a full detailed projection of the balance sheet may not be required to develop reasonable modeling and outcomes. As always, a vetted and complete projection of the financial statements is desirable.

Supporting documentation can take numerous forms. Reconciliation of modeling assumptions to external drivers, operating activities, market pricing, throughput capacity, supplier expectations and trends, bellwether industry peers and market participants, downstream and upstream expectations and many other supporting considerations is always helpful but generally lacking for many projections. Often, a review of the projections using such benchmarks leads to a modification or adjustment of the projections by management. In this fashion, the appraiser’s and/or trustee’s review serves to effectively adjust the projections before and/ or during their use in a DCF model – thus the need for a flexible and adaptive modeling platform built from the projection.

What are some typical warning signs that a projection may be too aggressive or pessimistic?

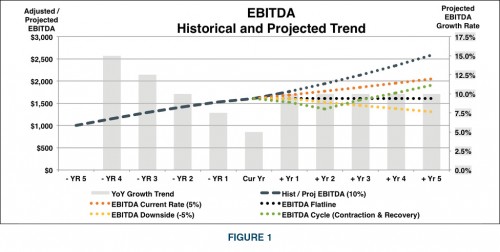

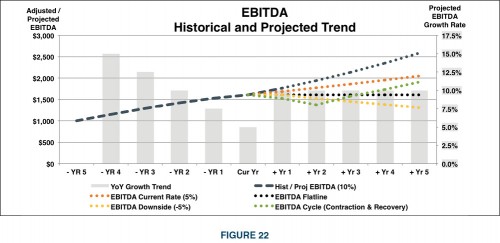

A baseline for assessing reasonableness or believability is always a good first step. A graphic representation of revenue, EBITDA and key volume measures can assist a reviewer in studying the reasonableness of a projection. Supernormal and/or counter-trend activity requires a compelling justification. Let’s use the information in the following graphic as a baseline for demonstrating some fundamental curiosity and addressing some basic questions regarding reasonableness.

The five-year trend for adjusted EBITDA at the valuation date reflects a pattern of strong growth (illustrated by the dotted blue line in Figure 1), but at a decelerating rate (illustrated by the columns in Figure 1). The projected annual growth rate for each of the next five years is 10%. In this case, management represents that the 10% annual growth projection is based on the compound annual growth rate for the five years leading up to the valuation date. This is an all too familiar “technical” rationale for growth forecasting. However, it begs the question of why the decelerating trend would suddenly flip favorable as opposed to continuing its decline or perhaps stabilizing at the most recent level of modest growth. Of course, the current trend could mature as a contraction in performance before an upturn that repeats the prior cycle.

Figure 1 depicts a wide variety of plausible alternative projections based on a technical review of the trend and a healthy dose of analyst scrutiny of management’s optimistic projection. The projection provided by management could easily be an order of magnitude overstated relative to other plausible outcomes. If EBITDA growth remains at the most recent rate (5% annually) then management’s projection is overstated 25% by year five (the orange dotted line). If EBITDA flatlines at current levels management’s year five projection is overstated by 60% (the black dotted line). If the deceleration of growth actually turns to a steady contraction (5% annually) then management’s projection is almost 100% overstated. If a modest near-term contraction is followed by a renewal of the previous growth cycle (the green dotted line), then management’s base 10% annual growth projection is overstated by 35% in year five. We could iterate infinite variations in future outcomes, but I submit that the variations shown above stem from a reasonable risk averse, conservative framework. The real concern is how well the projection reconciles to external and internal drivers that have proven to influence past business outcomes and/or drivers that are virtually assured to influence future outcomes.

In the present case example, the platform of management’s projection is built on the prevailing economy (generally favorable but inconsistent growth) and involves a market-beta industry (highly correlated to the overall economy). More specifically, the subject company is a construction contracting concern whose early growth began from a deep trough in the cycle, then was temporarily juiced with shovel-ready government funded activity which eventually dried up as the general economy stabilized. New norms are uncertain but project budgets and financings are expected to be more difficult as real interest rates become more than zero and underwriting hurdles remain quite high. In this light, a simple extension of the five-year CAG into the future for five more years appears to ignore the decelerating trend. Absent specific contracts and backlog, industry-based drivers, and perhaps geographic hotbeds of significant in-migration, management’s projection outcome appears over optimistic if not outright aggressive.

Projections that appear contrary to external trends and opportunities and which are not reconciled to the company’s capacity (whether existing or planned with the associated capital required) may need to be disregarded in the valuation process. Alternatively, the appraiser and trustee could view the projections with heighten concern for their realization and elect to effectively hedge the projections using appropriate discount rates, probability assessments, or other treatments that mimic the behavior of hypothetical investors. Ultimately, the reliance or weight placed on a projection based valuation method demonstrates the comfort of the appraiser/trustee with the method. If the final weights or reliance are placed on alternative valuation methods with materially different value indications than the DCF, the appraiser/trustee is effectively disregarding or modifying the projection. Surely, every valuation conclusion, under any valuation approach or method, has an underlying implied projection through which the same value outcome is produced.

Rules Of Thumb For Growth Rates

Recent Macro-Economic History

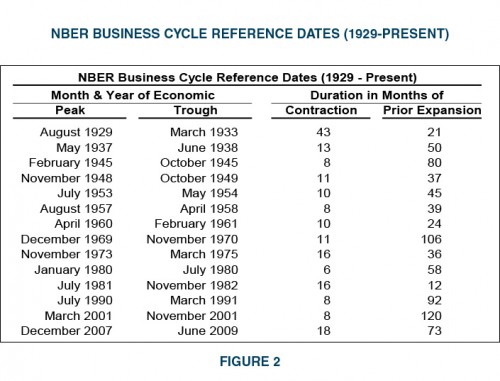

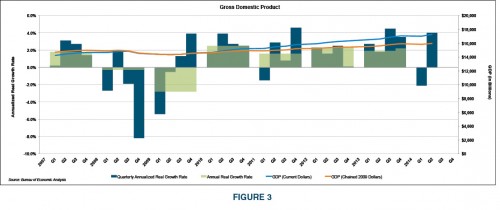

Assuming a company’s growth and/or projected financial performance is highly correlated to general macroeconomic growth is often an underpinning of long-term sustainable growth rates. Care must be taken when observing data reported from government agencies as such data can be “real” or “nominal” in quantification. Real rates are generally representative of movements net of the influence of inflation and nominal growth is generally total growth including inflation. Accordingly, growth rates in valuations that mirror inflation are effectively zero real growth rates. Gross domestic product is almost always reported and discussed in real terms, meaning the addition of a long-term inflation rate is typically called for in cases where the appraiser/trustee considers a company’s performance to be similar to that of the overall economy. For perspective, Figure 2 presents the history of economic cycles and the more recent performance of real GDP over the last several years (Figure 3).

On the basis of inflation of approximately 2.5% in recent years, nominal overall economic growth has approximated 4.5% to 5% subsequent to the great recession. Ah, the rule of 5% +/- for growth. There is a wide variety of alternative economic measures and subsets of GDP that could serve as a proxy for long-term sustainable growth in most valuations. Of course, such growth rates may fail to capture all the underpinnings of a given industry or market and may also fail to recognize the specific financial and operational details of a given company. Most companies tend to grow in phases as capital investment, hiring, product offerings and other business attributes evolve over time. This discussion could extend to an infinite spectrum of data and benchmarks.

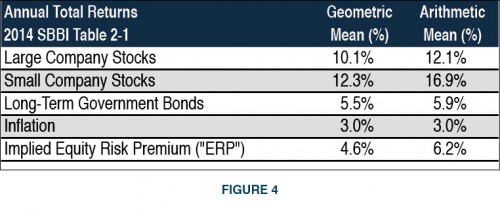

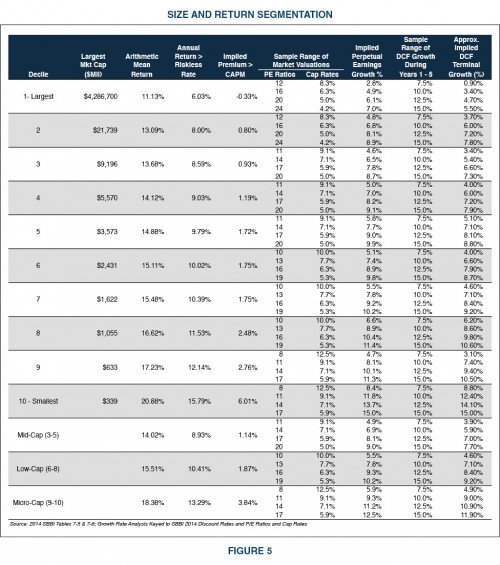

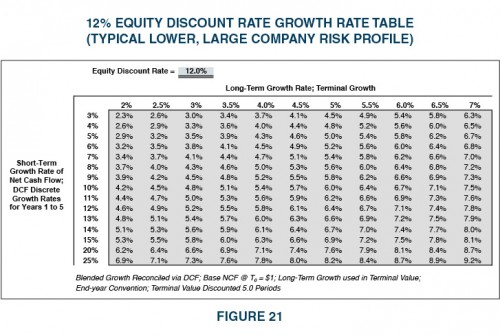

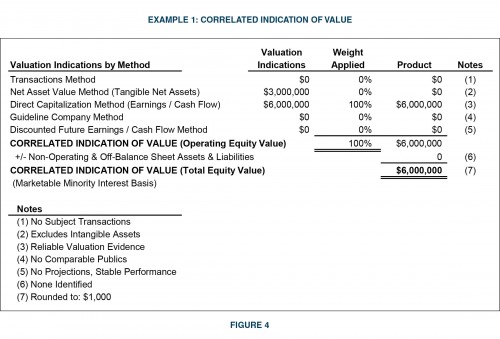

Equity Market Perspective

Appraisers employ various tools and data resources to determine the appropriate cost of capital for use in a valuation. Employing a bit of analytical deduction using the disciplines of the Capital Asset Pricing Model and the Gordon Growth Model, one can observe some tendencies regarding the markets’ implied earnings growth expectations. One of the most frequently employed resources is the annual Morningstar/Ibbotson SBBI publication. Given this data, and an assumed range of price-to-earnings ratios, one can deduce the implied perpetual earnings growth rates embedded in the market’s pricing over time. This framework can be applied to a specific company, a group of companies, or an industry. The example in Figures 4 and 5 demonstrates market-based influences regarding analyst predispositions about earnings growth over time. As with other tools and sensitivity analyses in this publication, changes to the inputs can result in significantly different outputs.

Relative to the growth dynamics of the different sized public companies depicted in the preceding table, it’s no wonder that the closely held, mostly mature, mid-market companies typically seen in the ESOP world (with enterprise values ranging from $10-$500 million) are imbued with net cash flow growth rates on the order 3% to 5% in the appraisal process (the “comfort zone” ). However, the timing of growth during the projection can be significant to a DCF value indication and can also influence growth rates in single-period capitalizations to measures outside of the comfort zone.

Framework for Studying Projections and Growth Rate Assumptions

By convention, virtually all business valuations include a presentation composed of five years of historical financial performance. Depending on the nature of the underlying financial reporting of the sponsor company, the presentation will include balance sheets, income statements and cash flow statements. The notes to the reported financials may also contain a myriad of underlying detail and disclosures supporting the chart of accounts displayed on the core financial exhibits. Commonly, these financial exhibits are augmented with derivative analysis to study the common size (percentage of assets) balance sheets, common size income statements (historical margins expressed as a percentage of revenue), financial ratios, peer/ industry data sets, and year-to-year and compound annual growth rate measurements.

The foundation for studying the reasonableness (or believability) of a forecast derives from a firm grasp of the relevant history of the subject enterprise. The reported financial statements are often recast to reflect the proper historical base from which most projections are cast. Ultimately, the valuation methodology captures the adjusted, pro forma financial performance and position of the company that serve as the appropriate base from which forecast results are projected to emerge.

Financial history is not the only context for vetting projections. To the extent possible, the financial exhibits should be annotated and/or augmented with operational data (and graphics) that allow the appraiser to demonstrate and consider how the company’s activities relate to its financial performance. In addition to common size financial data, revenue and profit segmentation can be critical to understanding what aspects of a business are performing well and what parts are hindering results. In addition to perspectives on revenue mix, the report should also reflect a functional unit volume analysis that promotes an understanding of how pricing and activity volumes drive revenue and profitability. In turn, these observations help inform the appraiser about the physical capacities, break even levels, labor resources, and other aspects of the business model and operational flows that should dove-tail with the projections.

For example, if a projection implies that a business will exhaust its current operating capacities or markets, then an adequate and properly timed charge to cash flow for capital expenditures should be included in the forecast to promote continued growth. Otherwise, little or no growth (beyond the price component of revenue) should be reflected in the model. Additionally, the duration of the discrete forecast should span the number of periods required for the company’s operating and financial performance to reach a reasonable normative state from which a steady level of continuing performance can be expected. Thus, a five-year projection may require augmentation of a few periods to regress a high-growth model to a mature state, or a negative growth model to a new state of sustainable performance. Ultimately, the timing of when growth occurs can be an important value determinant in a DCF model as well as a vital consideration to developing a perpetual growth rate for cash flow.

When assessing a perpetual growth rate assumption, which is required in a single-period capitalization of earnings or net cash flow, one key to estimating a reasonably correct growth rate is an understanding of the internal and external factors that drive the assumption. While some appraisers are of the mind that projections cannot or should not be developed by an appraiser; surprisingly there is no debate as to the requirement of postulating a perpetual growth rate. These seemingly different disciplines are in fact one in the same. Arguably, an appraiser seeking to quantify or justify a perpetual growth rate must employ elements of the DCF mentality to define what that growth rate should be. Of course, the base amount of the cash flow is a vital starting point. For those appraisers who gravitate to the 3%-5% perpetual growth rate range, the use of a multi-period cycle-weighted historical average of cash flow can create a significant error in the valuation.

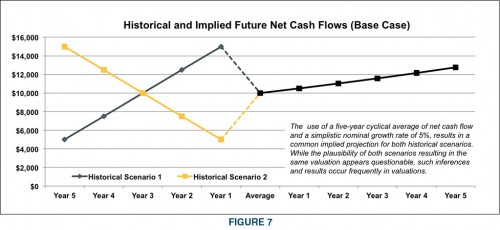

Let’s construct a simple example to demonstrate the valuation issues that could result from two different historical conditions that have the same average of performance. As crazy as it may be in practice, it is not uncommon for appraisers using multi-period averages to effectively ignore prevailing conditions and use a nominal long-term average growth rate that is correlated to GDP or some other prominent macroeconomic or industry performance measure. This mentality renders real time trends and real time expected directionality in performance as irrelevant. The following example is engineered to demonstrate how far astray the mentality for averaging and the failure to model growth can lead the valuation.

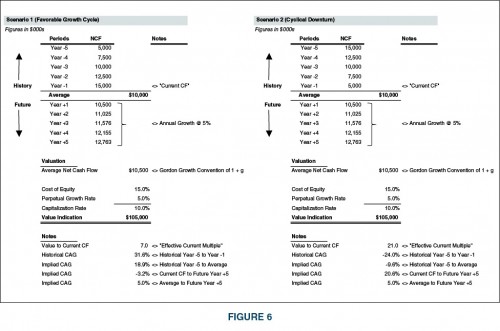

Example Conditions

- The average after-tax net cash flow is $10,000,000

- Depreciation and capital expenditures are substantially offsetting

- Incremental working capital needs are minimal

- The cost of equity is 15%

- The “assumed” perpetual annual growth rate in net cash flow is 5%

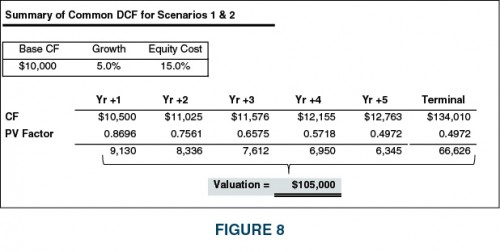

As can be seen in Figure 6, relative to the common valuation of $105,000, Scenario 1 represents undervaluation by approximately 30% (10 x $15,000 = $150,000) relative to recent annual performance, while Scenario 2 reflects an overvaluation by over 100% (10 x $5,000 = $50,000). More disturbing than two quite different trends giving rise to a common valuation of $105,000 is the spread of the value range from $50,000 to $150,000 derived from the “Current CF” measures of each scenario. Which valuation is more reasonable? Are there alternatives to modeling growth that represent more plausible projections or growth rates?

As can be seen in Figure 8, a valuation of $105,000 is derived from the two distinctly different historical scenarios. How might alternative projections be modeled that provide an enhanced perspective from which to study a reasonable perpetual growth rate for each scenario? Frankly, most seasoned valuation professionals would admonish the appraiser in each of the example scenarios for failing to study a projection that “engineers” the prevailing cash flows from their current respective conditions to an assumed cycle-neutral point five years hence. Simultaneously, how could a discrete projection be modeled that develops the value associated with a series of future cash flows that reconciles to a reasonable steady-state measure of cash flows and forward growth?

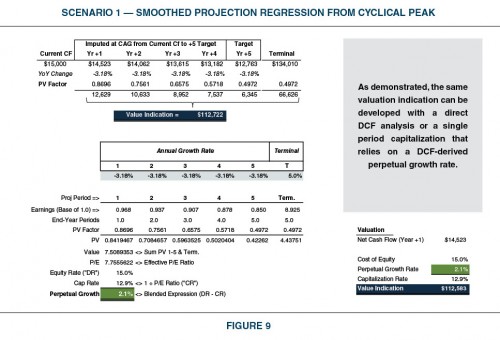

Taking Scenario 1 first, the five-year average cash flow ($10,000) results in a measure of cash flow well below the current performance ($15,000). What might a superior path of analysis be to capture the concern that current performance is unsustainable in the near-term? Substituting the implied growth rate of cash flow resulting from the assumed perpetual growth rate of 5% and a base average of $10,000, one might postulate a more believable pattern of performance and valuation as in Figure 9.

Note that the year five CF is determined as the same amount ($12,763) ultimately reached in both implied forward cash flow scenarios using the 5% perpetual growth from the base average cash flow of $10,000. An alternative modification to the original implied projection would be to regress the current cash flow performance ($15,000) to the forward year five adjusted base ($10,000 x 1.055 = $12,763). The valuation resulting from the modified projection is 7.4% higher due to a less abrupt decline than the default first year drop from $15,000 to $10,500. While this is not a radical percentage difference in the valuation, the alternative smoothed projection is a more intuitively appealing and believable model. Such a construct allows for analysis to support the development of a growth rate applicable to the cyclical high Current CF of $15,000. Using the following proof we can devise a perpetual growth rate that will reconcile the Current CF to a similar adjusted valuation of approximately $113,000.

Based on Figure 9, a growth rate of approximately 2% could have been reasonably applied to the Current CF ($15,000), lending enhanced credibility to a single-period capitalization than using 5% against the multi-year average performance of $10,000. The original, default approach used by many appraisers represents a 50% immediate first year disconnect from prevailing performance that lacks a reasonable basis. This is not to say that some circumstances don’t call for an abrupt shift in assumed cash flow versus prevailing cash flow, but that is typically a fundamental issue such as the loss or gain of a significant product, territory or customer. Too often this type of flaw is the result of the default five-finger rule to averaging five years of cash flows and using a 5% growth rate.

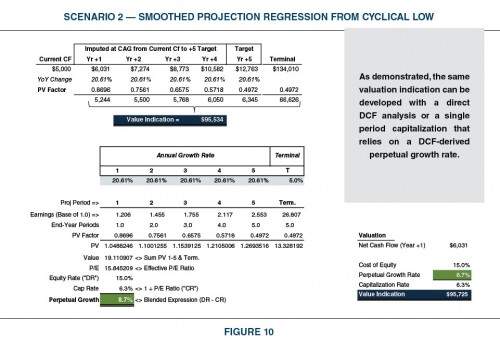

Repeating the previous exercise for Scenario 2 results in Figure 10.

Based on the example in Figure 10, a growth rate of approximately 8.7% could have been reasonably applied to the Current CF ($5,000), lending enhanced credibility to a single-period capitalization than using 5% against the multi-year average performance of $10,000. Again, this is not to say that some circumstances don’t call for an abrupt shift in assumed cash flow versus prevailing cash flow, but such a scenario is typically a fundamental issue such as the loss or gain of a significant product, territory or customer.

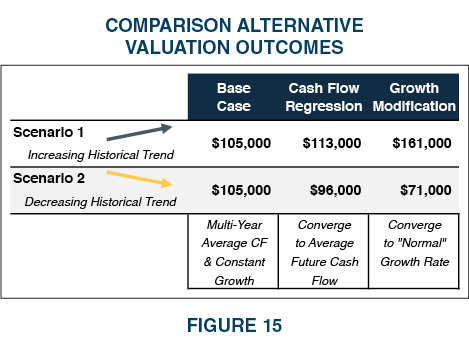

Now that both of the implied projections have been modified to reflect more gradual regression to a mean level of assumed stable performance and sustainable future growth, the valuations reveal differentials from approximately 7.2% higher to 8.9% lower relative to the $105,000 derived from the default valuation mentality often employed. More significantly, the respective valuations are better suited to the prevailing cash flows and the expected directionality of performance. Each model now reflects a more thoughtful consideration of the time value of money.

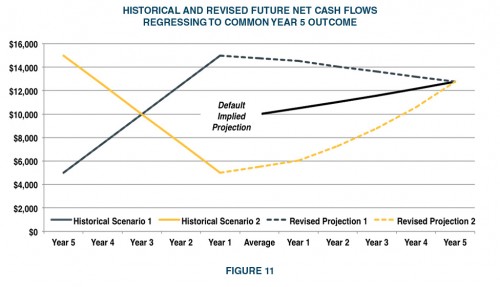

Figure 11 shows how the respective projections for each scenario converge on an estimated cyclically neutral level of future performance. The respective valuations, either in the form of a DCF or in the form of a single-period capitalization, are refined to capture the time value of money corresponding to a more believable performance regression/progression forecast. It should seem logical that the refined projection showing a gradual decline (Scenario 1) that starts with an above historical average level of performance, results in a higher value than the original $105,000. Likewise, the increasing projection (Scenario 2) that starts with below historical average performance results in a lower valuation than the original treatment.

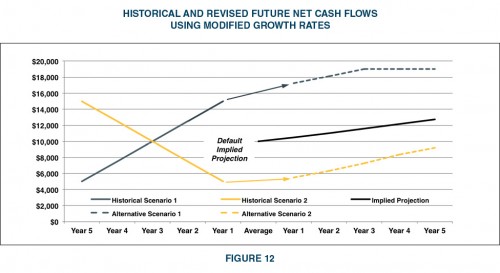

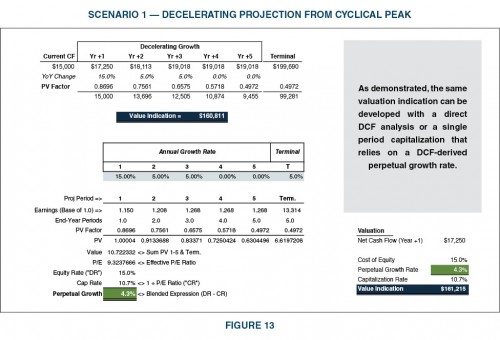

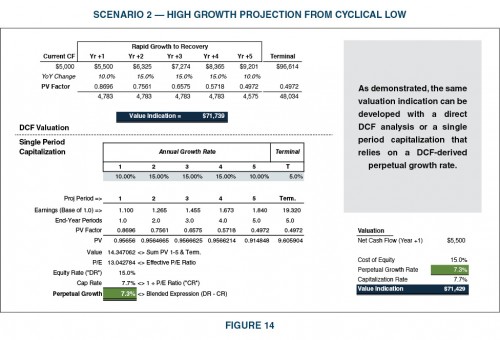

The chart in Figure 11 implies that performance has a gravitational attraction to the five-year outcome as a notional level of future performance ($12,763). An alternative and perhaps more realistic projection would craft a regression of the growth rate rather than a regression of performance to a notional future amount. Decelerating growth from either its peak performance (Scenario 1) or applying rapid growth during a mode of recovery (Scenario 2) seems more logical in most real world situations than the default trend. These competing projections are depicted in Figure 12. The valuations resulting from the smoothed growth patterns are developed in Figures 13 and 14 respectively. Of course, the pattern of future deceleration or acceleration requires specific study and support. The assumed patterns are presented for example purposes. A study of these alternative modeling inputs suggests that the original valuation of $105,000 is potentially flawed.

Let’s summarize the various valuation outcomes from the two different scenarios. Remember, common averaging techniques coupled with seemingly benign growth assumptions result initially in the same valuation under both scenarios. However, scrutiny of the growth and/or projection modeling reveals some dramatic differences. Admittedly, in most valuations there would be underlying facts and circumstances supporting one of three modeling conditions applied to each scenario. One can easily see how valuations can be viewed quiet differently by differing parties under differing circumstances. The primary valuation differential for each stems from the implied projection and growth modeling.

The common appraiser mentality of using historical average performance (rule of thumb mindset) combined with the typical “normal/benign” assumptions concerning growth and the cost of capital, can serve to understate or overstate value. Growth analysis and reasonable forecasting (birds of the same feather) allow for a more believable and optically pleasing analyses and conclusions. Comparing alternative projections from otherwise implied projections can provide better insight into growth modeling and promote more rational forecasting.

Appendix A | Case Analysis: Understanding Growth Rates

One of the most debated and poorly supported assumptions in business valuation is that of the growth rate in performance, be it earnings, net cash flow, or debt-free cash flow. The default reliance on macroeconomic or industry based data is a good beginning but often falls short of the full growth profile for a specific business in a specific industry in a specific geography at a specific point in time. The real world is often lumpy and most companies experience shifts in top-line activity, cost efficiencies, and operating leverage throughout the business cycle or in conjunction with changes in the business model. Skill and experience are powerful influencers for what feels “right,” but too often the five finger-growth mentality rules the day. What tools can an appraiser use to develop and defend growth rate assumptions and how can such a tool be used as a critical review tool?

Let’s study an example featuring a combination of typical facts and circumstances.

Example Conditions:

- The economy is stable, with nominal GDP on the order of 4% and real GDP on the order of 2%

- The subject Company is stable, and operating with consistent results

- The Company is twenty years old and has experienced 10% growth in annual sales over the last five years

- The subject Company has moderate pricing power and operates in an industry with commodity players as well as value-added players (implying a range of profit margins and revenue sizes)

- Historical pricing for the Company’s goods and services follows a more or less inflationary pattern (say 2.0%), and the markets resist price increases such that Company profits can be squeezed without constant attention to expenses

- The goal for the Company is to expand its market from the current 25 states to all 50 states in the next five years (all states represent equal market opportunity)

- With margins constant, sales growth represents a reasonable proxy for growth in earnings and net cash flow (EBITDA margin +/-10%)

- Public companies, larger and already national in market exposure, are expecting 5% annual sales volume growth over the next five years (consistent with industry expectations) and 10% annual earnings growth (implying margin expansion)

- Capital structure is expected to remain unchanged for the foreseeable future (debt free) » The Company has no excessive or abnormal risk exposures or concentrations

- The Company’s goods and services do not represent new or disruptive/paradigm technology

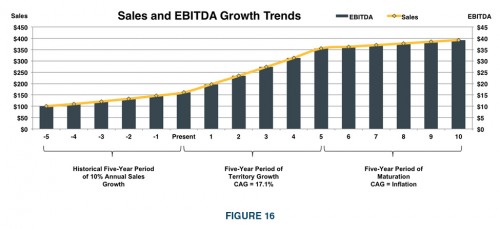

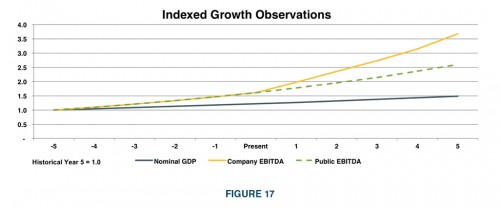

It is not uncommon for an appraiser to uncover the above information in the course of due diligence. Yet, the same management team that can relate such feedback to the appraiser will not “speculate” on a projection. A competent appraiser should be able to cobble together the framework of a projection for purposes of quantifying a growth rate for a single-period capitalization as well as performing a summary DCF analysis (perhaps as a test of reason or as additional direct valuation evidence). Figure 16 depicts how the facts and circumstances are expected to play out in sales and EBITDA.

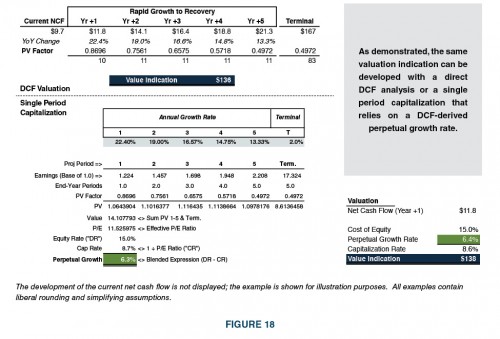

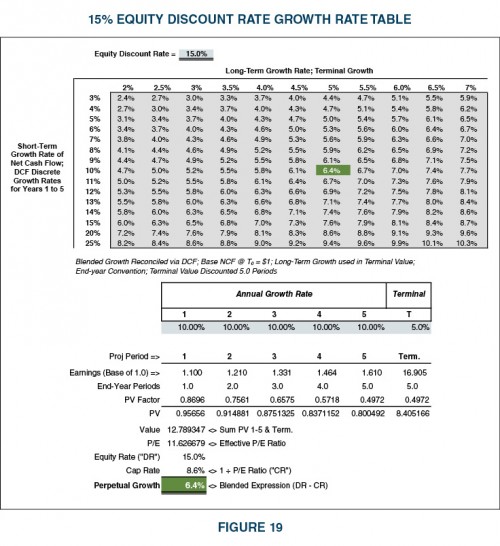

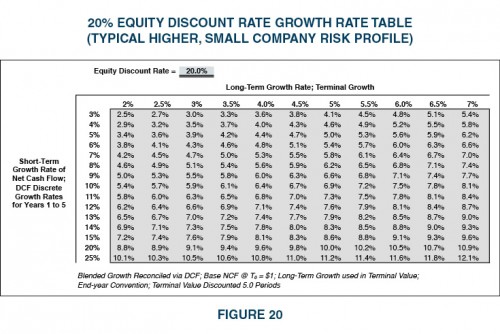

Most often the typical approach would be to grab a recent average level of performance and use a growth rate likened to nominal GDP (4%), perhaps influenced up a bit to reflect the recent growth performance. However, the 6.3% perpetual growth rate developed does not tie directly to the underlying data and general information. For an appraiser to get the single-period perpetual growth rate correct, he/she would simply have to get that “just right” feeling. Clearly, a bit of extra effort and the constructive extension of logic would allow for an anecdotal or direct DCF-type study that could offer support for the generally favorable growth rate required in the analysis.