Down and Out: Bankruptcy Valuations Portend Production Declines

Projections and reorganization valuations of some recent oil and gas debtors demonstrate that creditors are aiming to ride existing production out of bankruptcy as opposed to drilling their way out of it.

Oil patch producers have been plunging towards bankruptcy for several months now as I have written before. This trend is on pace to continue with WTI still hovering around $40 per barrel. Hopes for even $50 per barrel prices could be cathartic for many, but alas prices have been flat for months now. There are dozens of areas and fields that have become economic at $50 compared to $40. Somewhat ironically, one of the pathways back to higher prices will be the decline of production in the U.S. (if not replaced elsewhere). That appears to be the case for most producers already in Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

Whiting is a good example. According to its bankruptcy filings, projections show that Whiting is only expected to spend a paltry $6 million on capital expenditures in 2021 against $300 million in EBITDA. Cash flows are scheduled to be maximized towards claim recovery; particularly its reserve-based lending (RBL) claims of $581 million. As such, production is slated to decline steadily over the next five years as its creditors attempt to recover claims. Creditors’ priorities make sense from their standpoint. Even banks with financially stable clients are not advancing higher borrowing bases right now.

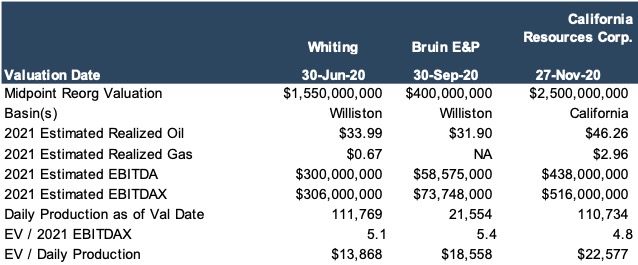

Whiting’s midpoint reorganization value as estimated in its bankruptcy documents is also primarily reflective of its cash flows from existing wells and not from prospective future wells and acreage. As such, its valuation, while steady from an EBITDAX multiple perspective, is towards the bottom of Mercer Capital’s range of publicly traded implied production multiples.

Whiting is not alone at these valuation metrics. Bruin, another bankrupt operator in the Williston basin, has a reorganization value of 5.4x projected EBITDAX and a production multiple of $18,558. Bruin also is expected to spend relatively little ($15 million) on exploration expenses, however, it also has 1/5th of Whiting’s production. While also at the low end of implied public multiples, Whiting and Bruin are at a higher premium than some in the market right now.

Another bankrupt company, California Resources Corp. has a higher production multiple than either Whiting or Bruin. This appears to be driven by substantially higher realized oil prices in California, and also potentially by shallower decline curves that lead to longer lived wells in the San Joaquin and Los Angeles Basins. It’s also remarkable that California Resources plans to spend more than Whiting and Bruin combined in 2021.

How do these values stack up in the transaction marketplace? Not a simple answer. First, there aren’t many deals happening in this environment and the ones that are happening are not in the Williston or California. One recent deal is Devon Energy’s purchase of WPX Energy. All three reorganization values lag the implied transaction multiple for WPX Energy. A Permian-based operator with an oil tilted production mix, WPX, transacted for $27,198 per flowing barrel according to Shale Experts. However, it is not surprising that it went at a premium to these debtors; with plans to limit future drilling, the debtors’ reorganization values are thus more heavily weighted towards PDP production than any other reserve category.

Additionally, the Permian has been a favored basin compared to the Williston and California in recent years. Amid this year’s turmoil, the Permian is still expected to lead U.S. oil growth for years to come. Depending on who one consults, the basin with the most amount of potential to return to profitability as oil crawls back towards $50 per barrel is the Permian. There are already a few top tier locations that are profitable at $35 per barrel, but those are limited locations and are mostly in the Delaware. Certain areas in the Permian contain several potentially economic locations between $40 and $50. In contrast, most of the Williston’s inventory becomes profitable at above $50 per barrel.

Still, as it stands at around $40 per barrel, only a handful of areas (mostly in the Eagle Ford and Permian) are profitable to drill right now. According to the most recent Dallas Fed Energy Survey, oil prices are expected to rise less than 10% by next year. Accordingly, drilling activity has turned anemic. Rigs, which as recently as a year ago were plentiful across the fruited plains, are as sparse as some endangered species. That will not change until oil gets back over $50 and where differentials between benchmarks and actual realizations are smaller.

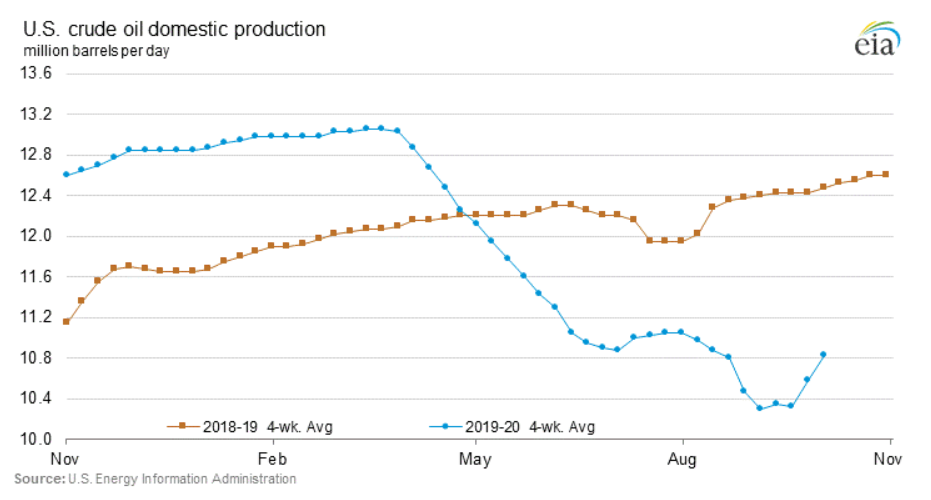

In the meantime, production could continue to fall off. Since March, production in the U.S. fell as far as 20% in September. This is a precipitous decline in a short amount of time.

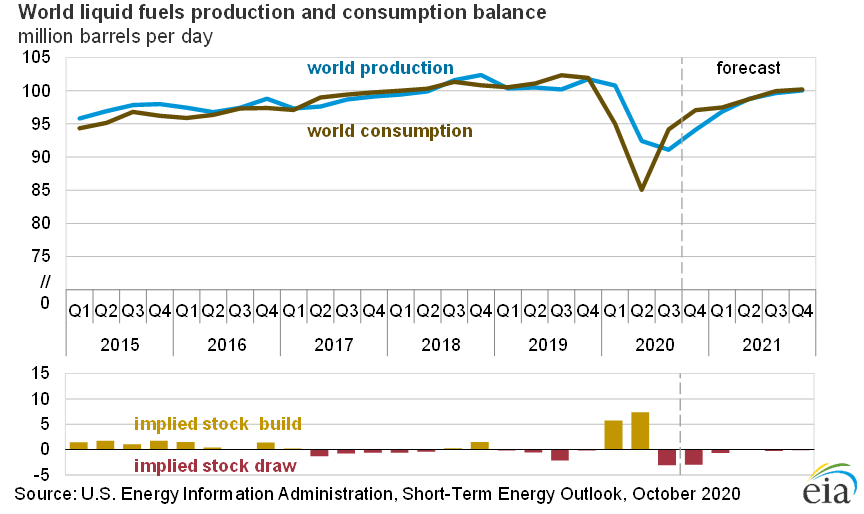

The chart above reflects not only the lack of new drilling, but the steep decline that shale oil wells intrinsically have. This will be a critical consideration in bankruptcy hearings. How steep will decline curves be and how much will revenues (and thus debt recovery) be delayed or impaired by these declines? Additionally, if OPEC fills the supply gap once demand returns, which it is projected to do, U.S. producers could miss some of the comeback especially with current China tensions.

That said, investment prospects remain cloudy as more look to get out than to get in. JPMorgan Chase just announced that it is shifting its financing portfolio away from fossil fuels. Although disputed by many experts, one of BP’s world oil scenarios contemplates peak oil as governments and markets shift away from fossil fuels more quickly than anticipated. ESG investing and stronger investor sentiments towards other fuel sources imply that its possible oil did in fact peak in 2019. If that is the case, then Whiting, Bruin and California Resource Corp’s creditors will be hoping that their debtor’s recovery will pick up alongside improving oil prices. If prices do not recover quickly then they will be joined by many more peers before 2020 ends, which will likely exacerbate more production decline in the U.S.

Originally appeared on Forbes.com on October 13, 2020.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights