Private Oil Company Values Are Readying For Take Off: While Publics Remain On Runway

As the term “energy security” comes back into the public lexicon, the values of U.S. oil companies are rising. This comes at the delight of some and chagrin of others. Regardless, it represents a foreshadowing of a potential longer-term cycle; whereby U.S. oil production being able to meet energy demands will be increasingly important. Many believe the U.S. is now the world’s “swing” producer (although John Hess disagrees), and it is not due to government action (or inaction). Biden’s third SPR release in the last six months is largely symbolic and more of a political gesture than a meaningful macro-economic needle mover. Demand and supply were drifting apart before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and this geopolitical dynamic has only widened that gap. The market participants best positioned to seize upon this unexpected gap are private U.S. operators.

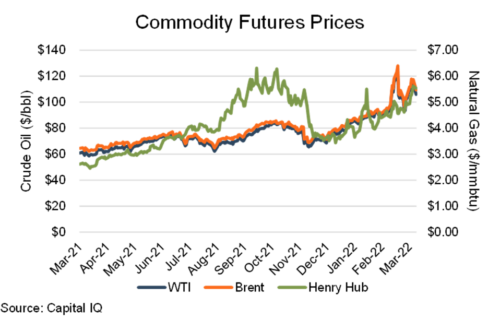

The current price expectations of oil make a lot of reserves economically attractive. The rate of return on capital deployed for drilling is going to (if not already) outstrip the demand for other capital deployment options such as dividends or debt repayment. However, most U.S. public companies are not shifting their strategies.

Domestic Dynamics (Not Russia’s) Keeping Public Valuations Relatively Grounded

As I have written before, shareholders have demanded returns from oil companies for years now in forms other than production growth. Oil company valuation in its fundamental form is a function of the present value of future cash flows. Therefore, if capital available today is best served in drilling more wells tomorrow, then production growth is the most efficient path to a higher value. At historical prices from a year ago, the decision to return more capital to shareholders (as opposed to deploying it in capex) made sense. It doesn’t now. However, public companies have yet to change the courses they’ve been setting for the past several years. That’s partly why the public sector (using XOP as a proxy) only rose 62% in the past year while prices nearly doubled.

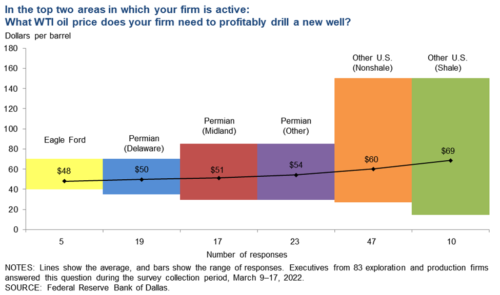

Demand is strong with the anticipated depletion of Russian oil on world markets. U.S. capital budgets would have to quadruple by the end of 2024 for shale to replace Russian oil exports to continental Europe according to Wells Fargo. In addition, break even prices in most basins for new wells are still around where they were a year ago according to the Dallas Fed Survey. That cost is going up and will continue to, but there is still lots of room for profitability at over $100 per barrel. Also, as I have mentioned before as well, DUC wells continue to shrink. In summary, there are a lot of signals to public companies to “drill baby drill”, yet they aren’t.

To be fair there are some caution signs on the horizon that should be considered and are baked into these public valuations. First, the futures curve is still backwardated, meaning that prices are anticipated to fall in the future (not rise). However, even the long-term NYMEX curve is still over $70 in four years, which is still profitable for a lot of reserve inventory. Second, new wells drilled today appear to be less productive. The EIA’s drilling productivity report shows that new well production per rig is going down (although they acknowledge that metric is “unstable” right now). Lastly oilfield services markets have become very tight:

“ Labor and equipment shortages, along with inflation in oil country tubular goods and shortages of key equipment and materials, will limit growth in our business and U.S. oil production. In particular, truck drivers are in critical shortage, perhaps due to competition from delivery services.” – Dallas Fed Survey Respondent

Private Companies Take To The Front

Enter the private oil companies. If forecasts suggest the U.S. can add between 600,000 and 800,000 barrels of oil by the end of the year (EIA says this can be 760,000) then the path to get there will be through the drill bits of private and private equity backed producers. According to an Enverus Report cited by Hart Energy, these types of operators have assumed the vast majority of new rig activity since the summer of 2020. With fewer external concerns, less ESG pressure, and lower regulatory costs, the private sector’s flexibility and nimbleness allow it to surge in front in search of the growth that the fundamental economics suggest is lurking.

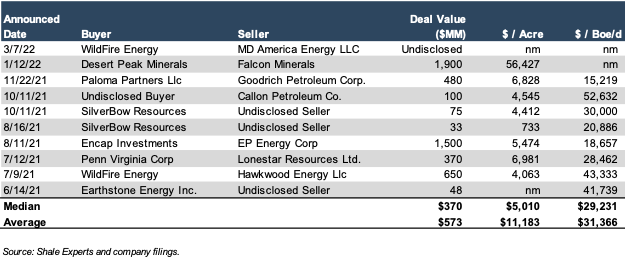

As an example, Mercer Capital’s latest merger and acquisition discussion focused on the Eagle Ford shale suggested that the market have signaled to potential buyers that the time was right to increase their footprint in southern Texas while conversely providing for an exit for sellers who could either capitalize on the prospect of a continued upswing in energy prices or redeploy capital elsewhere.

Whatever the exact incentives may have been that drove the M&A activity, the result was ten deals closed, mostly by private buyers or small-cap producers such as SilverBow Resources.

These implied valuation metrics in the table above suggest that there are outsized returns to be made on incremental new wells at the present time. Lots of eyes are turning to watch U.S. production, not only in the Permian, but South Texas, Oklahoma, and the Bakken as well. What they are seeing right now is public companies remaining grounded with their capital, while private companies could be leaving them behind – and quickly.

Originally appeared on Forbes.com.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights