Bridging Valuation Gaps: Part 2

The current low price environment is affecting the finances of many E&P companies. At Mercer Capital we recognize that whether companies are looking to sell reserves to improve their cash balance, or are trying to generate reorganization cash flow projections during a Chapter 11 restructuring, understanding how to value PUDs and unproven reserves is crucial to survival in a down market.

Option Pricing

One of the primary challenges for industry participants when valuing and pricing oil and gas reserves is addressing PUDs and unproven reserves. As discussed in the first post of this installment, if one relied solely on the market approach many of these unproven reserves would be deemed worthless. Why then, and under what circumstances, might the unproven reserves have significant value?

The answer lies within the optionality of a property’s future DCF values. In particular, if the acquirer has a long time to drill, one of two forces come into play: either the PUDs potential for development can be altered by fluctuations in the current price outlook for a resource, or, as seen with the rise of hydraulic fracturing, drilling technology can change driving significant increases in the DCF value of the unproven reserves.

This optionality premium or valuation increment is typically most pronounced in unconventional resource play reserves, such as coal bed methane gas, heavy oil, or foreign reserves. This is additionally pronounced when the PUDs and unproven reserves are held by production. These types of reserves do not require investment within a fixed short timeframe.

Current Pricing Environment: Challenge = Opportunity

As oil prices have dropped—the high WTI price over the past six months was under $50 and the low under $30—PUD values may drop from 75 cents on the dollar to 20 cents on the dollar or less. After the last Recession, some PUDs faced a similar, yet more modest, decline in prices. The price level recovery for PUDs in 2011 was partly attributable to the recovery in the U.S. and global economies, and partly due to increases in the price of oil.

Valuation would be made easier if we could determine when oil prices would rise again. Let us look then to see what might change prices going forward. The consensus is that five main factors have significantly increased the world supply of oil and driven down prices:

- The continued success of shale drillers in the U.S.

- OPEC’s choice to increase and hold production levels.

- The U.S.’s elimination of restrictions on crude oil exports.

- The recent lifting of Iran’s sanctions and the anticipation of additional supply from war-torn countries of Libya and Ira

- Oil consumption slowing down in countries like China.

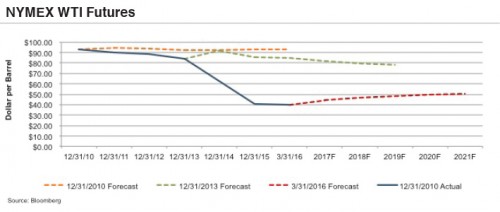

While this sounds promising, we must remember the crash in oil prices in 1985 that remained below $20 until 2003. Every analyst has a best guess of what will happen, but there are simply too many variables involved in shifting oil prices to make accurate forecasts. Changes in any of the five drivers of low oil listed above could dramatically impact oil prices; and some of those drivers, such as the relationship between Iran and Saudi Arabia or China’s growth—contain thousands of variables that make them almost impossible to predict. In addition to all these considerations, the potential for technological changes creates another unpredictable component. A common solution in DCF models is to use the NYMEX WTI futures to project price. However, studies show that, even though buyers are estimating the value of this option into the prices they are willing to pay, this too is not a very accurate predictor of the future. When NYMEX forecasts $35 per barrel it could actually be $45 when that future date rolls around.

Experienced dealmakers realize that the NYMEX future projections amount to informed speculation by analysts and economists which that many times vary widely from actual results. Note in the chart above how much the future forecasted prices changed in only one year. So what actions do acquirers take when values are out of the money in terms of drilling economic wells? Why do acquirers still pay for the non-producing and seemingly unprofitable acreage? In many cases they are following an options framework.

Real Options: Valuation Framework

PUDs are typically valued using the same DCF model as proven producing reserves after adding in an estimate for the capital costs (capital expenditures) to drill. Then the pricing level is adjusted for the incremental risk and the uncertainty of drilling “success,” i.e., commercial volumes, life and risk of excessive water volumes, etc. This incremental risk could be accounted for with either a higher discount rate in the DCF, a RAF or a haircut. Historically, in a similar oil price environment as we face today, a raw DCF would suggest little or no value for the PUDs or unproven reserves.

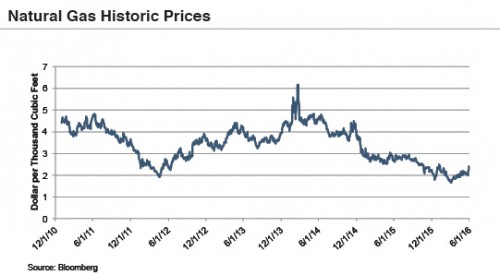

In practice, undeveloped acreage ownership functions as an option for reserve owners; they can hold the asset and wait until the market improves to start production. Therefore an option pricing model can be a realistic way to guide a prospective acquirer or valuation expert to the appropriate segment of market pricing for undeveloped acreage. This is especially true at the bottom of the historic pricing range occurring for the natural gas commodity currently. This technique is not a new concept as several papers have been written on this premise. Articles on this subject were written as far back as 1988 or perhaps further, and some have been presented at international seminars.

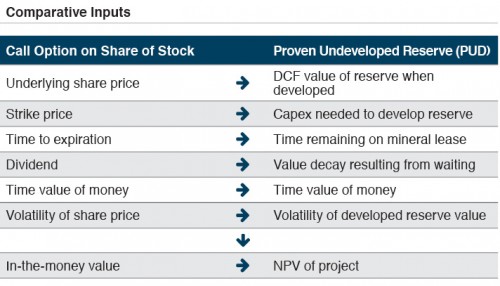

The PUD and unproved valuation model is typically seen as an adaptation of the Black Scholes option model. It is most accurate and useful when the owners of the PUDs have the opportunity, but not the requirement, to drill the PUD and unproven wells and the time periods are long, (i.e. five to 10 years). The value of the PUDs thus includes both a DCF value, if applicable, plus the optionality of the upside driven by potentially higher future commodity prices and other factors. The comparative inputs, viewed as a real option, are shown in table below.

When these inputs are used in an option pricing model the resulting value of the PUDs reflects the unpredictable nature of the oil and gas market. This application of option modeling becomes most relevant near the bottom of historic cycles for a commodity. In a high oil price environment adding this consideration to a DCF will have little impact as development is scheduled for the near future and the chances for future fluctuations have little impact on the timing of cash flows. At low points, on the other hand, PUDs and unproved reserves may not generate positive returns and thus will not be exploited immediately. If the right to drill can be postponed for an extended period of time, (i.e. five to ten years), those reserves still have value based on the likelihood they will become positive investments when the market shifts at some point in the future. In the language of options, the time value of the out-of-the-money drilling opportunities can have significant worth. This worth is not strictly theoretical either, or only applicable to reorganization negotiations. Market transactions with little or no proven producing reserves have demonstrated significant value attributable to non-producing reserves, demonstrating the recognition by some buyers of this optionality upside.

All that said, there are some challenges and dangers in applying the options model to reserves. These issues will be covered in part three of this series. To learn more about option pricing, and whether it could help your company reach optimal results either in sales or bankruptcy negotiations, please contact Mercer Capital. Conversations are in confidence, and our experts combine decades of experience in both oil and gas and bankruptcy to help you succeed.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights