Looking Back to Look Forward

We’ve made no secret of the fact that Family Business Director likes data. We are not economic forecasters, so we are not attempting to make any predictions about the coronavirus or its economic effects. However, in an effort to provide some context for ourselves, this week we decided to go back and examine some data from the Great Recession.

Specifically, we analyzed the performance of a group of small- and mid-cap public companies over the period from 2006 through 2011. This period allows us to see “normal” conditions prior to the crisis (2006 and 2007), two years of crisis performance (2008 and 2009), and two years of recovery (2010 and 2011).

The group we selected for analysis consisted of 554 companies having median revenues in 2006 of $853 million. We started with the current (March 2020) roster of companies in the S&P 1000 index (the sum of the S&P 400 Mid-Cap Index and the S&P 600 Small-Cap Index). We then removed financial institutions and real estate companies so that we were considering the performance of “operating” businesses. Finally, we removed companies that were not publicly traded through the entire period. There is a potential selection bias, as our sample includes only those companies that continue to be publicly traded 10+ years later. Nonetheless, it is the best we can do with our data resources, and we think the resulting data is still instructive.

We constructed an aggregate income statement and statement of cash flows for the group. You can see the detailed data here. Sifting through the data, we make five observations regarding how businesses persevered through the Great Recession.

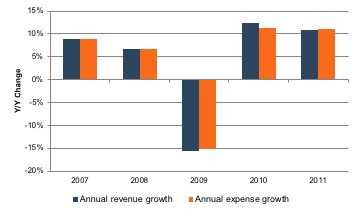

- Operating leverage can be managed. The first thing that struck us is how effectively companies were able to manage operating expenses to maintain profit margins. The textbooks tell us that, because some costs are fixed in the short-term, margins expand as revenues grow and shrink as revenues fall. While this is undoubtedly true, the data suggests that companies were able to manage costs more effectively than the theory would anticipate.

Exhibit 1 summarizes annual growth in revenue and expense for the years analyzed. In the face of a 15.6% drop in revenue during 2009, the companies in our sample trimmed expenses by 15.2%. As a result, EBITDA margin fell only modestly that year, from 12.0% in 2008 to 11.5% in 2009.

Exhibit 1

Annual Growth in Revenue and Operating Expenses

What steps can your family business take today to help preserve profit margins during a temporary revenue shortfall? How do you balance the near-term benefit of such steps against the long-term sustainability of your family business?

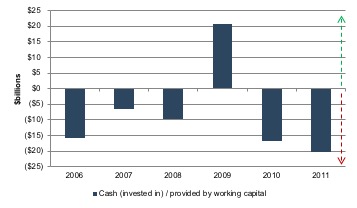

- Working capital really is a source of cash during a downturn. Cash management takes on extra importance during a recession. However, the data shows us that companies focused on working capital management can free up precious dollars by being intentional in inventory management and collections. As shown on Exhibit 2, the companies in our sample “found” $20.8 billion of cash by reducing working capital levels. For perspective, that’s nearly 12% of the total lost revenue of $175 billion during 2009.

Exhibit 2

Cash (invested in) / Provided by Working Capital

What strategies are available to your family business to help harvest cash from working capital during this cycle?

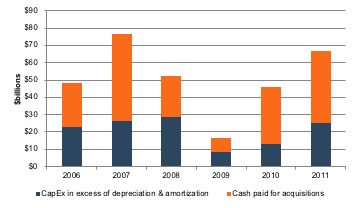

- Companies become more disciplined investors. One of the first things companies did to conserve cash during the Great Recession was to curtail investment spending on M&A and capital expenditures. Exhibit 3 depicts investment spending over the period. Relative to the 2007 peak, total investment spending decreased nearly 80% to the 2007 trough.

Exhibit 3

Aggregate Investment Spending

The data doesn’t reveal the answer to the most relevant question: what was the long-term impact of the dramatic reduction in investment spending in 2009? Revenue growth accelerated in 2010 and 2011 to rates higher than those experienced in 2007 and 2008. Part of that is likely attributable to pent-up demand from the weak results in 2009, but it does at least give us pause to wonder what portion of “ordinary” investment spending is effectively squandered by companies.

How will your family business prioritize investment opportunities during the Coronavirus downturn?

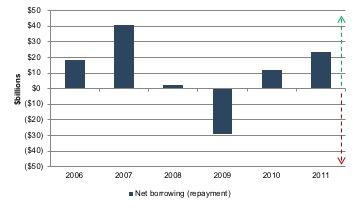

- Borrowers reduced debt levels. Whether by choice or by lender demand, companies repaid debt during 2009, in contrast to other years in which incremental borrowing is the norm. Exhibit 4 illustrates the net change in debt in each year over the period. After effectively eliminating incremental borrowing in 2008, the companies used $29 billion of available cash flow to pay back debt during 2009. For context, that represents about 83% of the $35 billion reduction in investment spending that year compared to 2008.

Exhibit 4

Net Incremental Borrowing (Repayment of Debt)

What is the status of loan covenants, credit line availability, and other factors that can influence your decision (or need) to borrow or repay debt in a downturn?

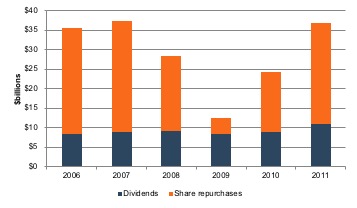

- Dividends were much less affected than share buybacks. Of the 274 dividend payers in our sample, only 57 reduced per share dividends during 2009, reflecting the powerful signaling property of dividend payments. Reducing the annual dividend is likely the last resort for public companies seeking to conserve cash. However, as shown on Exhibit 5, public companies tend to use more cash in share repurchases than dividend payments. From more than $28 billion in 2007, share repurchases fell to $19 billion in 2008, and bottomed out at $4 billion in 2009. The irony, of course, is that due to the depressed share prices, 2009 is precisely when repurchasing shares would have had the highest prospective return for public companies.

Exhibit 5

Aggregate Shareholder Distributions

Most family businesses don’t redeem shares as aggressively as public companies. As a result, suspending redemptions won’t conserve as much cash as it will for their public brethren. How have you prepared your family shareholders for a potential reduction in dividends? For shareholders deriving a significant portion of their annual income from family business dividends, any reduction can be unpleasant. How will you prioritize dividend payments against investment spending and debt reduction? Do your family shareholders know what your dividend policy is?

Conclusion

As we said at the outset, we are not professional economic forecasters. There are certainly many elements of our current situation that are far different than what we encountered over a decade ago. That said, the Great Recession was no walk in the park, either. Yet, companies of all shapes and sizes survived. As we have noted in previous weeks, it is our firm conviction that family businesses are better-suited to handling the type of adversity we are currently facing than non-family businesses.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director