Bones of Contention

The Complicated Dynamics of Family Redemptions

Earlier this month, Christie’s auctioned off a 40-foot long T-Rex named Stan. We were not aware there was an active market for such items, but an unnamed investor paid $32 million for Stan’s bones. That’s remarkable in itself, but our interest in the story was piqued upon learning why and how Stan was sold.

According to this story in the Wall Street Journal, Stan was found in the South Dakota hills by brothers Peter and Neal Larson in 1992. The brothers had been partners in their fossil-hunting enterprise since the mid-1970s. As happens all too often, unresolved disagreements between the brothers eventually found their way into the courtroom. The broad outlines of the disagreement are familiar to those involved with family business.

- Peter is the older of the two brothers and owned a controlling (60%) stake in the family business. Younger brother Neal owned a 35% stake, while a non-family partner owned the remaining 5%.

- In 2012, Peter suspended Neal and subsequently fired him for reasons that are less than clear.

- In 2015, Neal sued Peter claiming shareholder oppression. Neal’s preferred remedy in the suit was to liquidate the company and split the proceeds.

- It turns out that fossil-hunting businesses tend to be illiquid. In view of the company’s financial position, the judge ordered that Neal receive Stan in exchange for his 35% interest, with Peter and the other owner retaining all other assets of the business.

- At the time, Stan had an appraised value of $6 million, which according to the court’s ruling provided a “premium” to Neal.

- A couple of weeks ago, Neal sold Stan at auction for the aforementioned $32 million, which was 4x Christie’s high-end estimate prior to the sale.

Peter and Neal reportedly continue to live in the same small South Dakota town. The town is small enough that avoiding each other is not practical, but they do not speak. The story of Peter, Neal, and Stan highlights some of the challenges family businesses face when redeeming a significant shareholder.

The Challenges of Redeeming Family Shareholders

Many shareholder redemptions occur under circumstances comparable to that of the Larson brothers. One shareholder or family branch will continue to own and operate the business, while the other will have the opportunity to redeploy their net proceeds from the redemption however they choose. Oftentimes, that is truly the best outcome for the family, and may even preserve a modicum of family harmony, since the jointly-owned business is no longer a potential irritant.

However, when it comes to family business, it is probably never really over. Even after going separate ways, human nature is to continue looking over one’s shoulder to see how the other guy is doing. In the event of a shareholder redemption, there are three potential outcomes, two of which will create economic winners and losers in the redemption’s wake.

Scenario 1: The family business thrives and/or is sold at a premium to a strategic acquirer.

Sometimes, unexpected industry or economic tailwinds cause the family business to outperform expectations at the time of the redemption. Or, the remaining shareholders may eventually sell the business to a strategic acquirer who is motivated and able to pay a substantial premium to the redemption price paid by the family business. In either case, the portion of the family that stayed in the business enjoys the benefit of the company’s success, while the family members who were redeemed will naturally feel like the redemption price was unfairly low. Unless they prove to be savvy investors, the redeemed shareholders will fall behind the rest of the family economically. This can add unbearable strain to already tense family relationships.

Scenario 2: The family business performs in line with expectations and remains family-owned.

If the family business performs in line with expectations and remains family-owned following the redemption, there is a greater chance that both family groups will remain on broadly comparable economic footing, bringing with it an increased likelihood that family relationships can be maintained or even repaired over time.

Scenario 3: The family business struggles following the redemption.

In other cases, the family business founders following the redemptions. Whether through management miscues, adverse economic and industry dynamics, or because of the leverage used to fund the redemption, returns for the remaining family shareholders can be negative following the redemption. When this happens, the family shareholders that were redeemed become the “haves” and those who stayed in the business become the “have nots.” The family members who go down with the ship are likely to feel that the subsequent underperformance of the family business was attributable, in some measure, to an inflated price paid to the selling shareholders. As with the first outcome, family relationships prove hard to sustain when this happens.

Fairness and Risk

So what is fair in a family shareholder redemption?

The “fairness” of a redemption transaction cannot be evaluated by looking at the long-term outcomes for the two parties. The challenges encountered in executing a family shareholder redemption reveal the limitations inherent to a point-in-time valuation of any business.

The value of a family business at any given time is a function of expected cash flows and risk.

- When an investor buys a bond from the U.S. treasury, the expected cash flows are known with certainty. Under almost any conceivable future state of affairs, the owner of the bond will receive interest payments when due and will receive the principal payment at maturity.

- Investors evaluating a family business face a very different situation. However reasonable their projection of cash flows is at the time it is made, it will almost certainly turn out to be wrong, sometimes wildly so. This is the essence of risk. Risk is simply the width of the range of potential future outcomes. The greater the risk – the wider the range of potential outcomes – the lower the value of a business. The lower the value of a business, the higher the potential future returns to shareholders. Investors weigh risk when deciding how much to pay for a given business.

In a risky environment, a bad outcome does not necessarily mean that there was a bad investment decision. In the same way, when Scenarios #1 and #3 above occur, that does not necessarily mean that the shareholder redemption price was “wrong.”

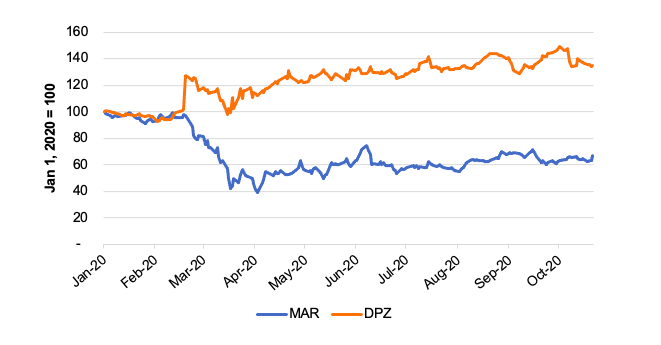

To illustrate, consider the diverging fates of two well-known consumer brands during 2020. The following chart compares share prices for Marriott International (MAR) and Domino’s Pizza (DPZ). The onset of the pandemic was devastating to business and leisure travel. When not traveling, people stay at home and eat pizza.

Does the preceding chart indicate that the share price for either company was “wrong” at the beginning of 2020? No. The shares of both companies trade in a deep and liquid market, and investors in both companies knew that a global pandemic was a possibility (albeit one to which they evidently assigned a low probability). The actual occurrence of the pandemic benefited DPZ shareholders and devastated MAR shareholders. But these differing outcomes do not mean that investors overpaid for MAR shares or underpaid for DPZ shares in January 2020. The buyers of MAR probably regret their purchase, but that possibility is the essence of investing in a risky asset. You may actually earn the higher expected return associated with a risky investment. Those who sold DPZ shares in January are likewise filled with regret, but that does not mean that they received an unfair price. They took their economic chips off the table, avoiding the risk of a massive food safety scandal that could have, but did not, materialize.

Conclusion

Your family business probably doesn’t own a T-Rex skeleton. Even so, a family shareholder redemption has the potential to trigger future wealth disparities in your family. Redemptions can make sense for a lot of reasons, but before executing a significant share buyback, directors and family leaders need to be aware of the potential pitfalls and make sure that all of their shareholders are educated about the risks that accompany any transaction. A regular process of recurring valuations can be instrumental in educating family shareholders to the risks that accompany ownership of a family business, provide greater clarity, and help set expectations when a redemption is called for.

Give us a call today to talk about how to get that process started for your family business.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director